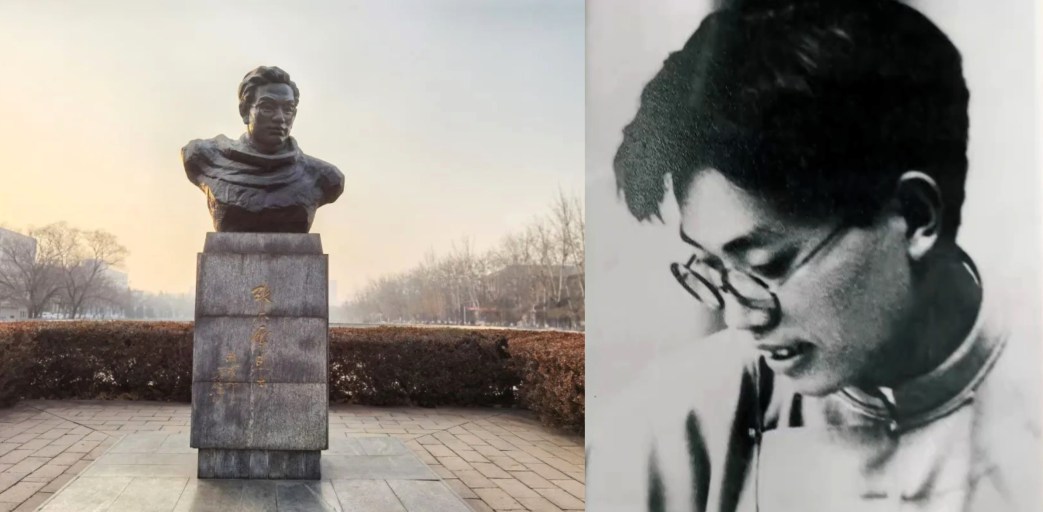

‘In Memory of the Organiser of the Canton Rising, Comrade Chang Ta Lai (Zhang Tailei)’ by N. Fokin from Communist International. Vol. 5 No. 6. March 15, 1928.

COMRADE CHANG TA LAI has been killed. Canton, the cradle of the Chinese revolution, has also become the grave of the young revolutionary, Chang.

Comrade Chang Ta Lai was born in 1898 in Chang-chow, a small county town; his family were small traders who had failed in business. Chang’s father died shortly after he was born, and he was left to the sole care of his mother, who dragged out an existence of semi-starvation. His relatives paid for his schooling. He first went to a secondary school, and then to the Peking university in Tientsin, where he studied law. Chang was the ringleader in all agitations and students’ movements in his school, which were directed against “the oppressors- the teachers.” The punishment meted out for these primitive forms of protest against antiquated school regulations and remnants of old social and family customs did not frighten comrade Chang, but led him on to the greater struggle for social liberty.

In the spring of 1919 the students’ agitation took on the form of a national liberation movement, directed first of all against Japanese imperialism, which had taken possession of Shantung, one of the richest provinces in China, and against the Treaty of Versailles, which had sanctioned this seizure. The fourth of May rising in 1919 was organised by the student movement. This revolt was marked by many spectacular effects, such as the demand for the boycott of foreign goods, the resignation of Cabinet ministers, the burning of their houses, suicide as a form of protest, etc., but it did not meet with the support of the masses of the workers and peasants, which might have given this revolt a real revolutionary character. Therefore, the actual results of this movement were negligible. The “fourth of May” camp began to split up. Some of the disillusioned participants threw “politics” overboard, devoted themselves to personal pleasures and became sex-mad. A peculiar type of Artzibashevism became the rage. Artzibashev’s sex novel, “Sanine,” was translated into Chinese, and became the standard or kind of bible for this type of student. It should be pointed out that the first form which the reaction of the Chinese students adopted was a refusal to participate in any kind of social life and a passion for sex problems. The increase in the literature dealing with sex problems, read mainly by students, was a proof of the desertion of the revolutionary movement by the students. For instance, in that year 57 editions of “Sanine” were published. A mass of periodicals and other literature was published dealing with sex questions, and enjoyed a popularity unheard of in the case of other publications.

Another group of those disillusioned with “the futility of their struggle and the silence of the mass” threw themselves into academic work, intellectual self-perfection for the preparation of “the new human being” out of oneself. A third type issued the slogan, “To the people!” and devoted themselves to the education and culture of the Chinese people in order to make them cap- able of accepting “the new ideas.” A fourth group began to listen to the rumblings of the fierce class struggle which was spreading throughout Europe and chiefly to China’s great neighbour- the Soviet Union.

Influence of Russian Revolution.

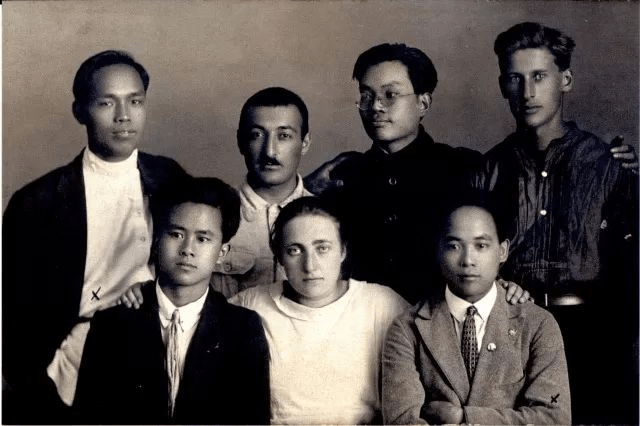

The October Revolution and the revolutionary outbursts throughout Europe during the period extending from 1917 to 1920 brought this section of the Chinese students under the influence of the ideological banner of the European revolutionary movement. Socialist theory began to secure a widespread following, numerous socialist organisations were formed. Special journals began to be published for the propaganda of socialism and Marxism. The more active elements of the “socialist” section of the students did not confine their work to the mere academic study of socialism, they flung themselves into the work of organising the masses of the peasants and workers to spread their ideas. Chang Ta Lai was one of these students. Together with comrades Li Ta Chao and Chang Go Tao, comrade Chang organised in Peking in 1919 the first group of the Young Socialist League, afterwards reorganised as the Young Communist League, which constituted the basis of the Communist movement in China. Comrade Chang having finished his studies, renounced his private life and legal career, and devoted himself completely to revolutionary Party work. He went to Shanghai, and there organised the first groups of the Communist Party and Young Communists, together with Cheng Tu Siu, the former leader of the Communist Party. Shortly after the First Congress of the Communist Party of China, in the summer of 1920, the Party sent him to Japan to work amongst the revolutionary emigrant workers there.

Comrade Chang Ta Lai was twice in Russia, the first time as delegate of the C.P. at the Third Congress of the Comintern, and the second time when the question of the entry of the Party into the Kuomintang was decided.

In the autumn of 1924, at the Fourth Congress of the Chinese Young Communist League, comrade Chang was elected general secretary of the executive of the Y.C.L.C. Shortly afterwards, in accordance with a decision of the C.P. executive, he was sent to Canton to act there as editor of the legal Communist paper, “The People,” which carried on an incessant struggle in its columns against the right-wing and centre of the Kuomintang. He defended, jointly with comrade Cheng En Liang, the theory, which many considered “heresy,” that the Kuomintang could not have an independent left wing, and that the policy of the C.P.C. should be directed towards winning over the hegemony within the Kuomintang. It is, therefore, not surprising that comrade Chang was the Communist whom the members of the Kuomintang hated most.

After the Kuomintang army had seized Wuhan he left for Hupei. In May, 1927, comrade Chang was elected a member of the Party, and appointed secretary of the Hupei Provincial Party Committee.

For the Peasants

Although comrade Chang was not free from certain opportunist errors which prevailed in the ranks of the C.P. at that time, still he had a keener feeling than others for the tendencies among the workers and peasants. He took an active part in the struggle against those leaders who agreed with the Kuomintang that the workers and peasants were guilty of excesses, and said that those who joined in the Kuomintang denunciation of the peasants as hooligans, etc., were not Communists but traitors.

The extraordinary conference of the C.P.C. which removed the opportunist leaders elected comrade Chang candidate to the provisional Polit-Bureau of the C.C. of the C.P.C., and he was soon appointed secretary of the Wuhang Dun District Committee.

Comrade Chang went to Canton when the province was in the throes of revolt. The peasants and workers had seized power in a number of districts; a fierce class struggle was in process both in the towns and villages. Now arms and ammunition were the order of the day, the time for flaming oratory had passed. The white terror gave place to the Reds. The struggle in Canton was centred around three military groups, Chang Fat Kwei, Li Fu Ling and Li Ti Sum. One strike after the other broke out, the workers seized the yellow unions, got rid of the leaders and took control of whole districts.

His Last Work.

It was quite clear to Chang that if the town did not take the lead of the civil war in the village, and if the C.P. did not develop the struggle to the highest pitch, that of revolution, then the Wuhan workers and peasants would not have sufficient support. Comrade Chang became the inspirer and organiser of the rising. He was everywhere, in the district committee, the staff headquarters and among the masses. For example, a few days before the rising comrade Chang called a conference, attended by 200 soldier delegates, at the grave of the 72 victims of the first Chinese revolution. His passionate speech induced the delegates to swear on oath to conquer or die in the attempt to establish the Soviet regime. The revolt of the Canton workers took place on the night of December 11th. The town was seized and the Soviet Power was proclaimed. The Canton workers elected Chang Ta Lai member of the Soviet Government, as deputy-president of the People’s Commissariat and the People’s Commissariat of War.

In those heroic and terrible days comrade Chang was everywhere where a leader or an organiser or a fiery speech was required. When he was making a speech he heard that the twice defeated militarist troops had invaded the town with the assistance of British cruisers. He rushed through the streets to the staff headquarters under a rain of shell, but on the way, he fell hit by a volley from the guns of the hirelings.

The revolution was defeated. Comrade Chang Ta Lai and thousands of unknown heroes were the victims, who point the way to the liberation of the Chinese workers and peasants.

All glory to the heroes of Canton. May the memory of the best soldier of the Chinese revolution, comrade Chang Ta Lai, live for all time!

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-5/v05-n06-mar-15-1928-CI-grn-riaz.pdf