A valuable history from Paul Frolich, transcribed for the first time, on the impact of Russia’s 1905 Revolution on both the debates with German Social Democracy and its effect on the larger workers’ movement.

‘The Revolution of 1905 and the German Working-Class’ by Paul Frolich from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 5 No. 76. October 26, 1925.

The Mass Movement.

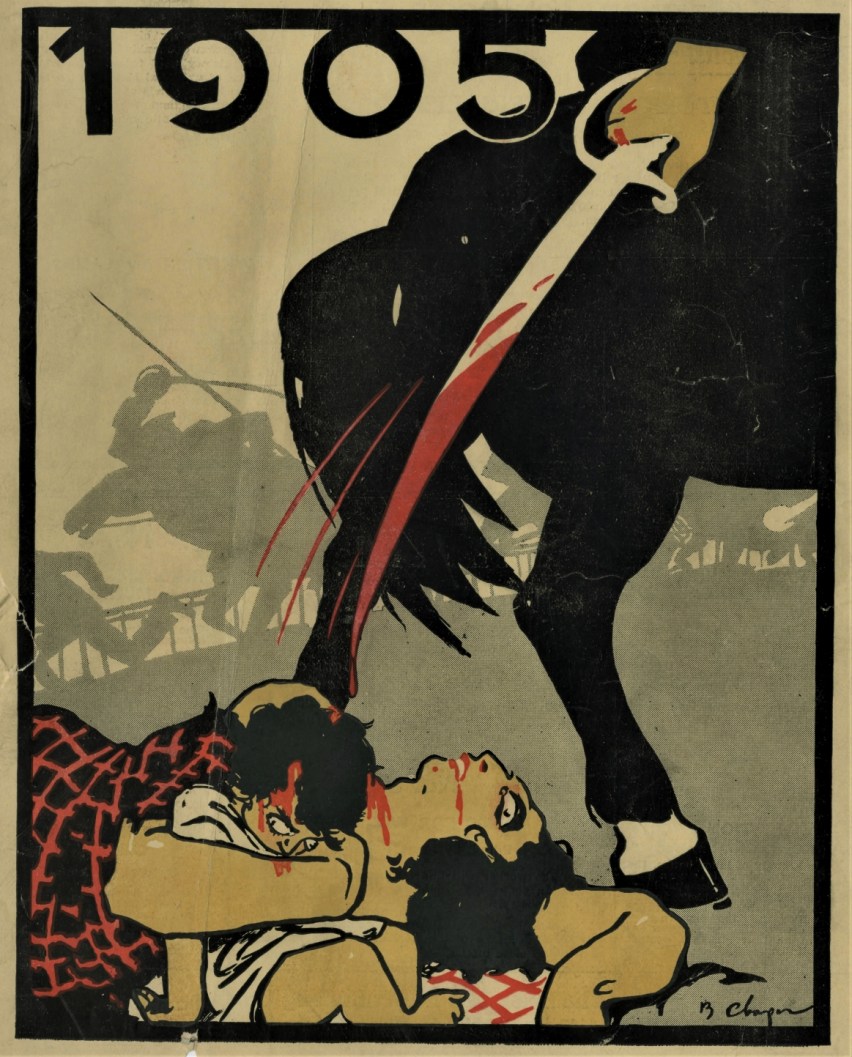

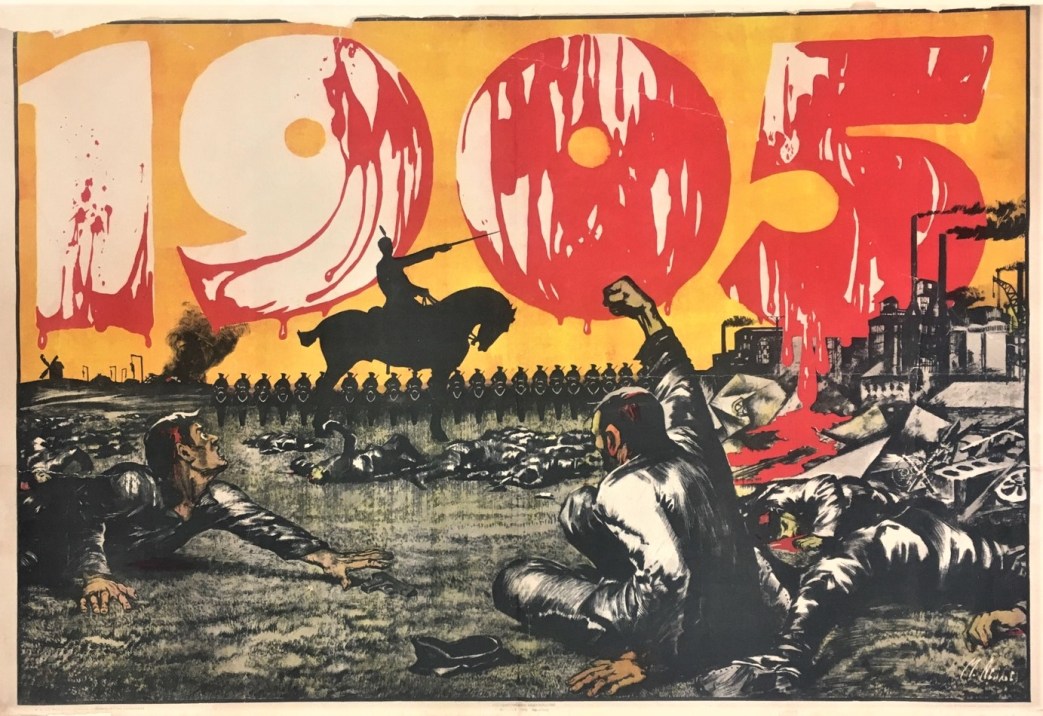

A decisive turning point in the history of German Social Democracy, a turning point in the direction of a real revolutionary party! This is what at that time seemed to us to be the immediate effect of the revolution of 1905 on German Social Democracy and the masses of the German proletariat. Had not the Party Conference at Dresden in 1903 finally overcome reformism? Had not the three million victory been a proof of the actual power of the German proletariat, and had not this victory demonstrated at the same time that parliamentary mandates have no decisive influence in class war, that the dice fall in the street, not on the parquet floor? It seemed to us that a period in the history of our party had been closed. And then the Russian revolution showed us the way that had to be trodden in the future. All we needed was to borrow from the experiences of the revolution against Czarism anything that fitted in to the revolution against the “civilised” capitalism of Western Europe and develop it further.

In any case the matter was very obscure. As regards one point however, we were right in our calculations. The German working class had, under the influence of the revolution, experienced a new intellectual revival. While itself lacking all revolutionary tradition, it had at least been a witness of this great historical birth pangs. An event which had been hoped for, doubted and dreaded, all at the same time, which had been playfully clothed by the imagination in lifeless romance, had become a reality that beggared all imagination. The German working class, it is true, like that of other countries, did not recognise the full import of the Russian revolution. The German proletariat was too conscious of the leading part it played itself, of the superiority of its own methods of fighting. The conception was too deeply rooted that the Russian revolution was merely catching up what was a matter of past history for Western Europe, the bourgeois revolution, and the forms it took, seemed to be a result of the barbarism of the Czarist regime. It was thought that they would vanish with the disappearance of Czarism and would leave way for Western European methods of fighting which they had newly fertilised. The permanent gain would be the strike of the masses as a means of bringing about a decisive fight. We have thus drawn in a few words a fair picture of the effect, the revolution of 1905 had on the minds of the Social Democracy workers.

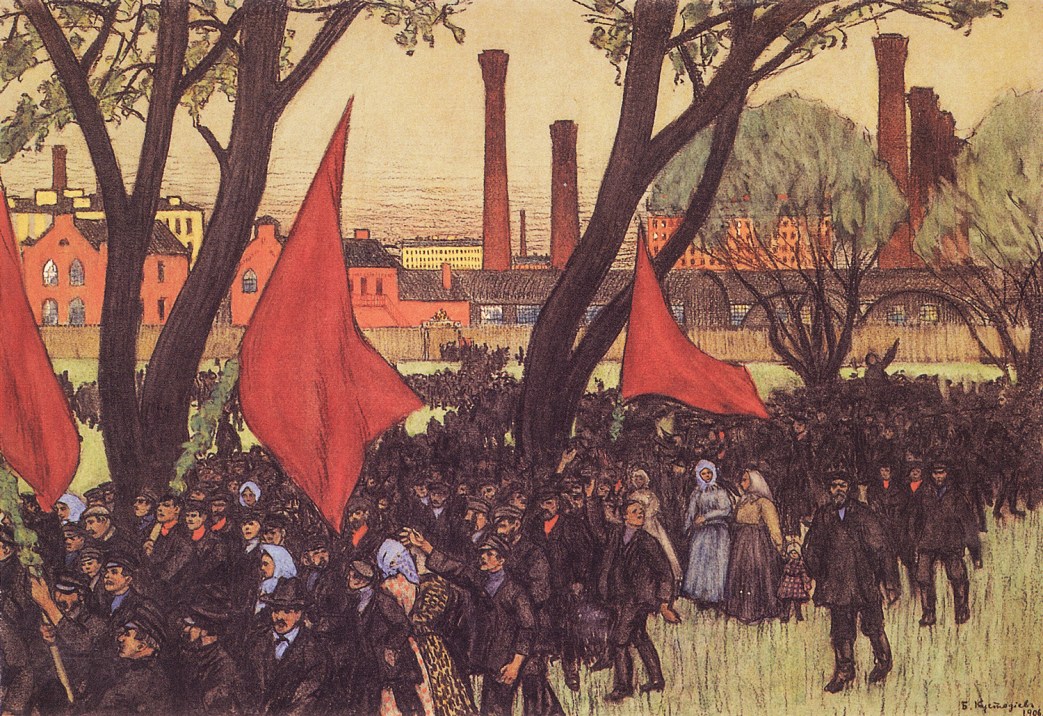

We do not of course pretend to have given an exhaustive description of its total effect. The fact that the giant proletariat of Russia had stretched its limbs filled the German proletariat with the consciousness of its power, and stirred it on to activity. A study of the events directly reveals how the stormy waves of the revolution spread beyond the borders of Russia and started movements in Western Europe which, it is true, were much weaker, but which nevertheless had the same rhythm of ebb and flow. Even the first culminating point of the revolution, the. great strikes, demonstrations and street-fights up to Jan. 9th 1905 were reflected in the great miners’ strike. This broke out on Jan. 8th as a result of the indignation at the arbitrary curtailment of wages, the refusal to pay the wages agreed upon if the wagons contained coal of poor quality, the scandalous lack of safety precautions, the overwork and the autocratic behaviour of the coal magnates. The strike funds were used up in a fortnight, but the fight was continued till Feb. 10th when it broke down owing to exhaustion. So far the strike was not a revolutionary movement, but its force, the fact that it attacked one of the vital sources of economic life and that it was a reflection of the great Russian strike of the masses, made it a political strike from the beginning, a means of exercising pressure on the State. The strike at least gained a considerable moral victory in that the Government was obliged to promise new laws regulating the questions concerning the miners. Needless to say, as soon as the immediate pressure was relaxed, these regulations turned out to be absolutely inadequate, a mere mockery of the miners’ demands. During the whole summer, strikes increased in almost all occupations. This was partly due, it is true, to the growing possibility of making profits, but undoubtedly it was also a demonstration of an increased sense of power and of a stronger will to fight. The Russian example took effect. It took such effect that even the “rocher de bronze” of German militarism received a few blows. This happened in July, during the “Kiel week”, William II’s usual great naval review. A short time previously, in the Black Sea, the “Potemkin” had delivered the first great revolutionary stroke, had hoisted the red flag and fired on Odessa. The crew of the cruiser “Frauenlob” mutinied in Kiel harbour during the great review, they locked up their offficiers, sank parts of their guns and hoisted what the first reports described as a “dirty rag”, probably the red flag. The crew declared that they had resorted to these drastic measures as a protest against the despicable way they were treated by their officers, and in order to enforce improvements in their conditions. When Willie of Hohenzollern saw the flag of revolt waving on the “Frauenlob”, he was beside himself with rage and he banished the ship from his august sight into the open sea. The action of the crew of the “Frauenlob” was in any case a powerful revolutionary gesture, and a revolutionary party leadership could have made considerably capital out of it. But the party contented itself with a few jibes at the naval administration and was glad to let the dangerous subject drop.

The Czar’s October Manifesto brought in its immediate train the first great franchise movement in Germany. The movement started in Austria and this gave an impetus to the German workers. The German bourgeoisie had already responded in its own way to the Russian revolution. It tried to entrench itself behind new political privileges. In a number of the separate States, especially in the towns of Hamburg, Lübeck and Bremen, a further restriction of the franchise, with the object of preventing the threatened flooding of Parliament by Social Democracy was discussed. In South Germany on the other hand some concessions had been made to the workers. This only made the contrast all the more marked in the two chief States of North Germany, Prussia, where the Parliament of Junkers barred the way to any political progress like a bronze bastion, and Saxony, where in 1896 the three classes franchise had been introduced with the result that in the “red kingdom” it was just one social democrat who was elected. The first street demonstrations in Saxony took place on November 19th and, from that time onwards, they recurred every week with steadily increasing violence. The movement spread beyond Saxony. On Jan. 17th, the first half-day demonstration strike took place in Hamburg. It made a great impression. All the workers of Hamburg left the works at one blow. Traffic was at a standstill in harbour and town. Large numbers marched in enormous processions to the meetings which were called to protest against the robbery of the franchise.

The culminating point of the mass movement was on the anniversary of the great massacre in St. Petersburg, Jan. 22nd 1906 (Jan. 9th Russian style.) In the whole Empire meetings and demonstrations were held at which the Russian revolution was celebrated and the will of the proletariat to conquer democratic rights for itself, was proclaimed. “Red Sunday” gave the German workers a faint glimmering recognition of their own power. This recognition, however, was not followed up. In Russia the power of the revolution was broken by the suppression of the Moscow insurrection, and the mass movement in Germany was nipped in the bud.

These mass movements of the year of revolution appear very moderate when looked back upon from this distance and, when compared with the raging sea of Russia, they are only a slight ripple on the surface of German political life. Things must be looked at from the point of view of their own day, and viewed in this light, the huge strikes and the first great street demonstrations mark an enormous step forward. Here was the possibility of fostering and furthering the revolutionary spirit of the German workers. But the authorities! That clumsy block-brake!

The Party Authorities and the Revolution.

The impetus and will of the German proletariat would undoubtedly have sufficed for much more powerful blows if the party itself had not so fatally failed to come up to the scratch. The small group of revolutionary socialists, gathered round Rosa Luxemburg, Clara Zetkin and Franz Mehring, it is true, did everything in their power to promote understanding of the international significance of the Russian revolution, to stimulate inspiration and to spur on to action. The “Gleichheit” (Women’s organ of Clara Zetkin) and the “Leipziger Volkszeitung” reached a summit of revolutionary journalism. Some other papers did very good work, but on the whole we are shocked at the lack of understanding, pusillanimity and weakness shown.

A few characteristic examples. On July 5th 1905, 6 months after the outbreak of the revolution, the party leaders, in a proclamation, called the attention of the eagerly listening world to the great event. They declared that the German proletariat must rush to the assistance of its fighting brothers by collecting money. The International bureau had at least in February demanded that “a share be taken in the work of liberation in the form of action, influence and propaganda.” The “Vorwärts” had at that time printed the proclamation without drawing any conclusions, without even a word of encouragement, as though by merely printing it they were fulfilling an irksome task. When the bourgeois Press made use of the proclamation of the party. leaders in an agitation against the terribly revolutionary German Social Democrats, the central organ had the pitiful courage to rage against the “forgery”, as though the German party had the intention “to proceed in the same way, if the Russian re- volution took the favourable course which was hoped for.” (The money collections for the revolution brought in more than 300,000 Marks.)

In Jan. 1905 that disgraceful secret alliance trial took place in Königsberg in which the Prussian vassal performed a labour of love for his Czarist master. The affair had its echo in the Reichtstag! It was one of those numerous opportunities of joyfully confessing one’s faith in the Russian revolution and of exerting influence in favour of the revolution from the Parliamentary platform. What a disgrace! Hugo Hasse held a juridical lecture in which he demanded that the Prusso-Russian extradition treaty should be terminated by notice!

The German Government of course openly took the side of the blood-guilty Czar. No opportunity was taken (Chancellor’s budget etc.) to pillory it.

In Jan. 1905 it was announced that the German troops on the Eastern frontier had been alarmed. The “Vorwärts” wrote: “Surely it is out of the question, in spite of everything, that Germany should go to the help of the Czar.” In the summer attempts were made to recruit White Guards for the Baltic barons. This is merely reported, that is all! In March the Russian workers on strike issued an appeal to the comrades in Western Europe to hinder munitions being supplied to the Czarist Government. The “Vorwärts” found it very difficult to discover where munitions for Russia were being produced. Altogether a supply of this kind is a violation of International Law. The German Government therefore should be the first to be on the watch.

This was the pitiable policy of the central organ and of the papers allied to it, as well as of the party leaders. It should be pointed out that the authorities and the Reformists instead of making use of the recent lessons, made every effort to make it seem impossible that the German working class would ever begin “to speak Russian.” This was due not merely to considerations for the public prosecutor. The idea that certain things which no one dared say openly could be expressed in illegal publications, did not even occur to them. Even then the party showed its true character although it was not yet recognised.

below (from left to right): Alwin Gerisch, Paul Singer, August Bebel, Wilhelm Pfannkuch, Hermann Molkenbuhr, 1909.

The picture would however give a false impression if only this sad side was seen. The more the efforts made to hush things up were evident, the greater became the contrast between Reformists and Radicals; as for instance when Clara Zetkin in her speeches ridiculed “the awe of the word legality”; as in the inspired speeches and writings of our Rosa; as in the great discussion after the mass strike. So strong was the pressure of these Radicals, that something unprecedented in German Social Democracy happened, that the party leaders pulled themselves together and turned the Reformists out of the “Vorwärts”. The attitude of the “Vorwärts” to the Russian Revolution was thus not the only but the chief cause. The “revolt of the journalists” ended in a reconstruction of the editorial staff. (Oct. 23rd, 1905.) Rosa Luxemburg also became one of the new directors of the paper, and wrote on the Russian question until, early in December 1905, she plunged into the whirlpool of revolution and took over the leadership in Warsaw.

This victory of Marxism and Centralism over Reformism and the professional privileges of journalism would certainly not have been possible without the Russian revolution which in this case also had led the party beyond itself and its innermost nature. It was and continues to be the only victory of this kind, and very soon afterwards the “Vorwärts” under the leadership of Cunow who was joined later by Hilferding, descended to being a willing tool of the dull policy of the authorities.

The Debate on Mass Strikes.

The great debate on mass Strikes is another example of a very promising rise and a deplorable fall. The radicalism of German Social Democracy culminated in it, and the Russian revolution assisted at its birth. The great Russian strikes in 1904 had already fertilized the idea of a general strike. At the Party Conference in 1904, Karl Liebknecht had proposed that the subject should be discussed the following year, but the suggestion met with very little encouragement. The great strike in January broke the ice. At the same time Henriette Roland-Holst’s epoch making book on the general strike appeared. After that the authorities could no longer stand aloof from the idea.

The old radical majority of the party was unanimously in favour of the general strike, though they had different opinions as to its significance and the possibility of putting it into practice. The Reformists were divided. One group under the leadership of Bernstein and Ludwig Frank was enthusiastic for the general strike as a means of defence or of conquering the universal franchise, not as a revolutionary weapon but for the creation of a solid basis for the Reformist policy. Another group of Reformists, which included practically all the trade union leaders, was against the general strike.

The first decision on the question was made at the Trade Union Congress at Cologne in May 1905. Bömelburg, one of the best types of trade union organisers, made the chief speech. It was full of the counter-revolutionary spirit and a demand for peace. The Congress, with tumultuous applause, passed the following resolutions: “The Congress condemns all attempts to fix on definite tactics by propagating the political general strike, and recommends organised workers to oppose such endeavours with all energy. The Congress considers the general strike, as it is represented by anarchists and persons without any experiences in the sphere of the economic struggle, beneath discussion. He warns the workers against allowing themselves to be distracted from the daily detail work for the strengthening of Labour organisations, by accepting and spreading such ideas.” Only 30 delegates voted against this resolution.

The “Vorwärts” wrote, entirely in the spirit of these timid enemies of revolution: “There is a danger that the imagination of the workers will be directed towards uncertain hopes and distracted from their more important and immediate tasks by a zealous study and discussion of such questions quite apart from the fact that continuous talking about and threatening with revolution is more likely to increase the reactionary hostilities against social democracy than to educate the working class to firmness of purpose.” This spirit was also a fruit of the revolution, but a rotten fruit.

The conspiracy against the idea of the general strike was thus the first to hold the field, and it represented a strong bloc of Labour bureaucracy. It was paralysed however by the fresh advance of the Russian revolution in the summer of 1905, the new wave of strikes, the barricade fights in Poland etc. The consequence was that they hardly dared to take an active part in the Party Conference at Jena. With tremendous enthusiasm and tumultuous applause, the general strike was recognised as a means of struggle by the whole party.

After the zenith of the Russian revolution was passed, a secret conference of trade union leaders was held in the Spring of 1906, at which war was declared on the party and especially on the radical wing round Rosa Luxemburg and the “Leipziger Volkszeitung”. At this conference the communication was made that the leaders of the party had capitulated to the General Com- mission of the trade unions. In the course of negotiations between the two authorities, Bebel had made the following statement: “The party leaders have no intention of propagating a political general strike at present. Should it become necessary to do so, the party leaders will previously come to an agreement with the General Commission.” At the party conference at Mannheim in 1906, there was a scene of reconciliation between the party and the trade unions. The trade union leaders made a show of submitting because they actually had victory in their pockets. The deception was exposed by a proposal of Legien in which it was established that the resolutions of Jena (the general strike as the strongest weapon) and of Cologne (prohibition even to discuss the general strike) do not contradict one another. Nowadays we recognise clearly that the Mannheim Party Conference had already shown the incapability of German Social Democracy ever to carry out a great political strike of this nature, and that the party had learned practically nothing from the Russian revolution.

The Attitude of the German Party to the Tactical Questions of the Russian Revolution.

In general it may be said that the German party had very little understanding for the internal questions of dissension among the revolutionary parties of Russia. They did not even understand the differentiation of the parties. They regarded it as the result of the squabblings of the emigrants. All the same, the individual groups of German Social Democracy spontaneously took up the attitude corresponding to their character. Thus Kurt Eisner in the “Vorwärts” openly sided with the Social Revolutionary Party. The Reformists greatly regretted that Russian Social Democracy declined to fraternize with the bourgeois opposition, the Cadets etc. The German Party hardly distinguished between the Mensheviki and the Bolsheviki. Their essential differences were not understood but the Bolsheviki were condemned as narrow-minded, intolerant secessionists and separatists. In the most important tactical questions, Rosa Luxemburg sided with the Bolsheviki against the Mensheviki.

Karl Kautsky’s attitude deserves to be described in greater detail. He was among the few who had begun early to concern himself with Russian party questions and with the question of the Russian revolution in general. He arrived at a point of view which was closely allied to that of the Bolheviki. As early as in 1902, he combated the conception that the proletarian revolution would be most likely to break out in the country which was economically most highly developed. He saw the approach of the revolution in Russia and recognised that the proletariat would play such an important part in it, that even in the International the Russian proletariat would take the lead. In an article on the American worker, written in February 1906, he wrote: “The Russian proletariat shows us our future.”

The revolution of 1905 was in general regarded as the last bourgeois revolution. But the Bolsheviki, and with them Kautsky. went a step further. Kautsky replied to a questionnaire of Plechanows’s (“Neue Zeit” 1906/7, No. 9): “The bourgeoisie does not belong to the driving forces of the present day revolutionary movement in Russia, which therefore cannot be described as a bourgeois movement. This does not however justify anyone in saying that it is a socialist one. It is incapable in any case of procuring for the proletariat the sole rule, the dictatorship; the proletariat in Russia is too weak and too undeveloped for that.” He was nevertheless prepared to admit the possibility of Social Democracy becoming so strong in the course of the revolution as to gain the victory. This led Kautsky on to answer Plecha- now’s second question, that concerning the allies: “It will however be impossible for Social Democracy to gain the victory through the proletariat alone without the help of another class, as the victorious party therefore, it will not be able to carry out its programme any further than is compatible with the interests of the party supporting the proletariat… It is only between the proletariat and the peasantry however that a solid community of interests for the whole period of the revolutionary struggle exists…Cooperation with liberalism must only be taken into consideration where and in so far as it does not interfere with Cooperation with the peasantry. The revolutionary power of Russian Social Democracy and the possibility of its victory are based on the community of interests of the industrial proletariat and the peasantry.” He admits indeed that this puts a limit on the revolution; even if Social Democracy were temporarily in power, socialist production could not be introduced. “And yet”, he continues, “we may still experience many surprises. We do not know how long the Russian revolution may continue, and in view of the forms it has now assumed, it does not seem likely that it will come to an end very quickly. Neither do we know what influence it may have, and in what way it may fertilize the political movements in Western Europe.”

Kautsky considers that the solution of the agrarian problem is the central question of the revolution, and with this object in view he recommends that strong dictatorial measures be taken: the confiscation and distribution of landed property, confiscation of the whole of the private property of the Imperial family and of the monasteries, national bankruptcy, confiscation of the great monopolies such as the railways, oil-wells, mines, foundries etc. In the “Neue Zeit” 1904/5, No. 41, Kautsky, referring to the theme under discussion, says:

“Had the will of the Liberals of past days been fulfilled and had the revolution come to an end with the transformation of the General Estates into the National Assembly in order to make way for a regime of law and order, briefly, had the revolution remained so “fine” according to bourgeois notions, as it is glorified in Schiller’s “Wilhelm Tell”, and had the French revolution not been “blemished” by the “reign of terror”, the lower classes in France would have remained absolutely immature and impotent politically, there would have been no 1848 and the fight of the French, and with them of the international proletariat for emancipation would have been indefinitely delayed.”

Here then we have a glorification of dictatorship and, by its context it is evidently recommended for Russia. There still remained the question of insurrection. After the Moscow insurrection, the party maintained an embarrassed silence. The “Leipziger Volkszeitung” (Paul Lensch) stated that insurrection is not a weapon in the proletarian struggle, that this had been proved in Moscow. Kautsky nevertheless, on Jan. 28th 1906 wrote in the “Vorwärts”:

“Should there again be a general insurrection as in October, it will probably not be limited to a general strike. And here we see another difference between the Battle of June in Paris and the Battle of December in Moscow: both were barricade fights, the former however was a catastrophe, the end of the old barricade tactics, the latter the inauguration of new barricade tactics. And in this respect we must revise the opinion expressed by Friedrich Engels in his preface to Marx’ “Class War”, the opinion that the era of barricade fights has come to an end. It is only the time of the old barricade tactics which is past. This was proved in the battle of Moscow in which a handful of insurgents held at bay for a fortnight superior troops armed with the equipment of modern artillery.”

There is hardly any gap in this descriptions of Bolshevist tactics. Every sentence shatters what the same Kautsky has said about the Bolsheviki since 1917. At the time Kautsky stood alone in the German party in the firmness of his point of view. But it is significant for the Kautsky of those days that, for the German Labour movement, he only drew the conclusions, the practical carrying out of which did not have actually to be faced. Even in those days, facts showed that neither Kautsky nor the German party was capable of drawing the real conclusions from the experiences of the Russian revolution, and that, should re- volution appear on the agenda in Germany itself, both would fail. Kautsky had to become a traitor, German Social Democracy had to become a counter-revolutionary party. The Russian proletariat had to give a new and more powerful example, and a revolutionary party had to be called into being in Germany.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1925/v05n76-oct-26-1925-inprecor.pdf