‘Fritz Lang and ‘Fury’’ by Robert Stebbins from New Theatre. Vol. 3 No. 7. July, 1936.

In 1929, it was possible for Paul Rotha, the eminent British movie- historian and documentaire, to say of Fritz Lang: “One regrets his entire lack of filmic detail, of the play of human emotions, of the intimacy which is so peculiar a property of the film.” But that was some five years before M, and seven before Fury!

When Mr. Rotha penned those words, Fritz Lang, already in his forties, had won wide acclaim for The Spy, Siegfried, and Metropolis, his only film besides Fury to be widely distributed in America. As a general rule, most artists at forty have their greatest achievements behind them. Fritz Lang’s art, however, has been a consistently unfolding, ripening phenomenon, both in human and filmic terms. Today we see him at the height of his powers confronted with the strong probability that soon there will be no place for him to work. At the present writing it appears that Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer does not intend renewing Lang’s contract. We wonder if it can be because Fury will make their remaining films look so childish, so hopelessly redundant? What is more to the point, is that the man’s integrity must have proved extremely trying to the Hollywood producers.

Integrity, honesty of purpose, lies at the foundation of the entire conflict between Lang and MGM or any true artist and Hollywood. For Fury, with all its limitations, is among the most honest, forthright films to emerge from a Holly wood cutting-room. Here you will find no sly prurient preface to concupiscence, no Graustarkian pipedream of which Bartolomeo Vanzetti once said “…these romances that distort truth and realities; provoke, cultivate and embellish all the morbid emotions, confusions, ignorances, prejudices and horrors; and purposely and skillfully pervert the hearts and still more the minds…”

True, Vanzetti’s keen and fiery mind would have immediately seized upon the compromises in Fury. He’d have pointed out that the second half of the film almost renders invalid its object by shifting the emphasis of guilt from the lynchers to vengeful Joe Wilson (Spencer Tracy); that by contrast with the ingrown, embittered maniacal creature Joe becomes- (he even pulls a gun on his brothers and threatens to kill them if they don’t go through with his plans)- the lynchers are portrayed sympathetically. Katherine (Sylvia Sidney), Joe’s sweetheart, pleads for them: “You might as well kill me too and do a good job of it. Twenty-two, twenty-three, twenty-five, what’s the difference? Oh Joe! a mob doesn’t think, doesn’t know what it’s doing.” Vanzetti would have pointed out that the institution of lynching has an economic and racial background that is necessary to a complete understanding of the problem and that the film was faulty for the want of it. He’d have proceeded to point out that almost eighty percent of the lynched are Negroes. And lastly, he’d scorn the likelihood of the innocent, dead or alive, receiving legal justice. In his own words, “There is venom in my heart, and fire in my brain, because I see the real things so clearly, to utterly realize what a tragic laughing stock our case and fate are.”

Apart from these weaknesses, in all probability compromises demanded by the box-office experts and not of Lang’s making, Fury is the most forceful indictment of lynch justice ever projected on a screen. In fact, with the exception of certain sequences in M, Fury is entirely without parallel. Not that lynching hasn’t figured in films before! The Westerns crawl with them. But in every case- Frisco Kid, Barbary Coast-the vigilante is upheld as a noble example, a cow-punching Cincinnatus come to rescue Rome from the alien invader.

To accomplish his ends, Lang has lavished a stupendous fund of illuminating detail on the film. The scenic recreations under the art direction of Cedric Gibbons, William Horning and Edwin B. Wells are extraordinarily effective. The recent revival of Taxi, with its fine realistic interiors, made me realize how much Hollywood has lost in exchange for the gold and ivory of the penthouse period. Unlike the sets and appointments in Taxi, however, the scenic reconstructions of Fury not only convince but even add to a comprehension of the principals, and at times, actually advance the story. When Joe embraces Katherine underneath the “El” the pillars, though almost wavering in the darkness, in their rigidity express the loneliness and heartbreak of the lover’s impending separation. When Joe returns to his incredibly untidy apartment you sense at once Joe’s life with his brothers and understand the great attraction that Katherine, with her neat school- teacher orderliness, has for him. There are too many instances of Lang’s remarkable grip on realistic detail, both scenic and directorial, to include within the limited scope of this piece. Suffice it to mention the moving solitariness of Joe in the business man’s lunch with the Negro bartender and the raucous radio; and that masterpiece of fidelity, the facade of the County jail.

The brilliant use of the newsreels in the court room is another case in point. Lang originally hit on the idea in Liliom. You will remember that in the Lang production of the play Liliom goes to heaven. There the good Lord, instead of reading Liliom a list of his misdemeanours from the book of books, shows him a news reel of his mortal life. But what was a pleasant device in Liliom, in Fury takes on a cogency and moral force that is terrifying. The tremendous contrast between the piteous woman on trial for her life and the insane caricature of herself she sees on the screen, murderously whirling the firebrand around her head, is a warning to all who take to the rope or torch for the destruction of a fellow human.

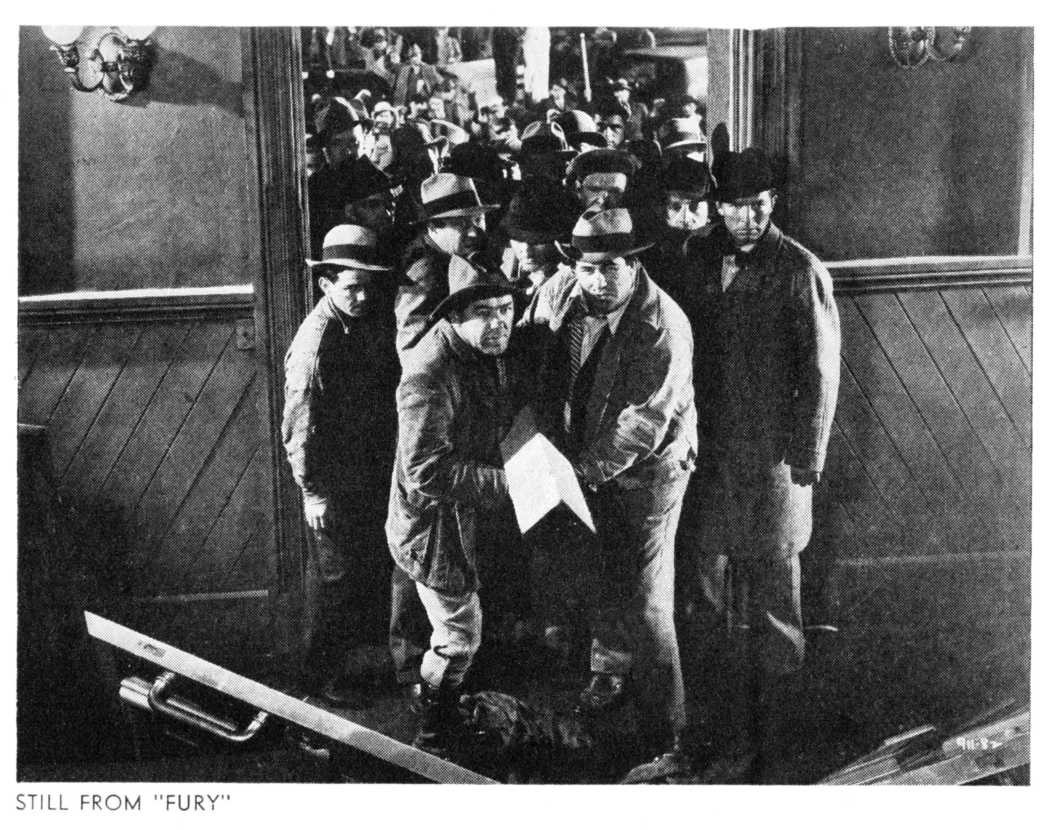

The chief glory of the film, however, is the thrillingly dissected and synthesized lynching perpetrated by the brutalized and excitement-starved lower middle-class shop-keepers aided and abetted by the chamber of commerce in close collaboration with the gangsters, hoodlums and strike-breakers of the town. From Joe’s arrest by the slow-witted “Bugs” Meyers, who later is unobtrusively shown nabbing flies on the wall while Joe is questioned by the Sheriff to that unforgettable moment when Katherine staggers into the square of Strand to find the entire town hypnotized by Joe’s supposed funeral pyre, Lang has given us a memorable example of film making at its apogee.

Felicitations for splendid performances are due the entire cast, are due Norman Krasna for his superb screen original (how he ever got it past the front office is nothing short of a miracle), and Bartlett Cormack for his work with Lang on the screen-play. Bartlett Cormack, however, although a screen librettist of un- deniable talent, in his propensity to break out in a voluntary rash of red-baiting, shows unfortunate promise of becoming the Zioncheck of the writers’ colony. A week after the preview of Fury he inserted the following advertisement in the Hollywood Reporter:

BARTLETT CORMACK* WROTE THE SCREEN PLAY OF FURY, A DRAMATIZATION OF SOME ‘CELLS’ OF THE UNITED STATES, RATHER THAN OF THE UNITED FRONT AND IS PROUD OF IT, AS A GOOD JOB, AND OF ITS STUDIO** AND ITS BOSSES, i.e. captains of entrenched greed, FOR HAVING MADE IT WITH ENTHUSIASM, AND WITHOUT SQUEAMISHNESS OR STINT.

* Member Sons American Revolution. ** Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Assuming that MGM’s decision to go through with Fury had nothing to do with the unprofitable and sulphurous egg they laid, called Riffraff-assuming that MGM got the idea all by itself, totally unaffected by the constant hammering of liberals against the fascist proclivities of the producers, even then, it is too early for Bartlett Cormack to crow. The latest indications, if we are to judge from Douglas W. Churchill’s article in the New York Times of June 14th, are that MGM never wanted to make the film and even today considers it a mistake. If Mr. Cormack will permit I should like to quote one last time from the letters of Vanzetti. Somehow Fury brings Vanzetti inevitably to mind. His letter of May 25th, 1927, to Mrs. Sarah Root Adams, mentions a note a friend once sent him in which she describes the treatment she is taking for her broken arm.

“…My arm’s bone refused to heal again for quite long time, then the Doctor recurred to electricity, apply it to my fracture and I recuperated quickly and well. How sorry I am to think that this same force which healed me may be applied to you.” I venture to state that for every film that will heal suffering mankind, there will be 20 to slay the Saccos and Vanzettis. I am afraid MGM is not yet on the side of the angels.

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v3n07-jul-1936-New-Theatre.pdf