Today, December 11, is the anniversary of the Guangzhou Uprising of 1927. Here, one of its instigators defends the uprising’s validity and possibility of success. Veteran Georgian Bolshevik Vissarion Lominadze was in 1927 a Comintern representative to China where in August he facilitated the removal of C.P. leader Chen Duxiu, who was blamed for the failure of the Comintern’s own policy of working within the Koumintang, and promoted a new leadership around Qu Qiubai. That new leadership was tasked with organizing an uprising, which would take place that December and would be known at the time as the Canton Commune. The crushing of the commune would forever alter the Communist struggle in China, and its consequences on the Comintern were equally profound. A member of the ‘Young Stalinist Left,’ Lominadze, and his position that China was ripe for socialism, a position refuted by Bukharin- then leading the Comintern, and would take the blame for the failure of the uprising. By 1930 he found himself in opposition to Stalin and would be demoted to secretary of the party in Magnitogorsk, a small city in the Urals. In January, 1935 he was summoned to answer questions in anticipation of the trial ‘Trotskyite-Zinovievite Terrorist Center’ and took his own life.

‘The Historical Significance of the Canton Rising’ by Vissarion Lominadze from Communist International. Vol. 5 No. 2. January 15, 1928.

ALL the information which has reached us so far concerning events in Canton have as their source only the communications of correspondents of the international bourgeois press and the imperialist agents of Reuter etc. These communications are “made” in the Pacific Ocean citadel of British imperialism, in Hongkong. It goes without saying that it is impossible to depend on the accuracy and disinterestedness of information coming from such an envenomed slanderous source. We are still far from knowing all the truth about the Canton rising. But with what an impression of greatness that truth must be stamped, since even now, through all the lies and insinuations of the bourgeois press the rising of the Canton workers emerges in such an heroic light and in such grand outlines! The Canton rising is the first big independent action of the Canton workers in the struggle for political power. The Canton workers struggled not in a bloc with the national” bourgeoisie, but in an alliance with the peasantry and the poor of the city against the bourgeois and landowning reaction. In this struggle the Chinese proletariat now emerges in the role of leader and director of all the oppressed classes of China. The Canton rising was carried out not under the banner of the Kuomintang, but against the Kuomintang and under the banner of the Soviets. The political position of the Chinese proletariat in December is incomparably more solid, the proletariat itself is much more matured in the revolutionary sense, than in March of last year. This is borne out by the gigantic dimensions of the Canton rising. And though the Canton workers were not able to consolidate the revolutionary position, though the revolutionary government of the Soviets in Canton lasted a still shorter period than the government of the revolutionary Kuomintang in Shanghai in its time, the causes of this lie not in the political, but in the military and technical weakness of the Chinese working class; not in the hopelessness of its alliance with the peasantry and the city outcasts, but in the fact that the bourgeois-militarist reaction with its preponderance of military forces flung itself on insurrectionary Canton before the peasantry could succeed in rising to answer the call of insurrection. The December rising in Canton excels the March demonstration of the Shanghai workers in its historical significance to the extent that the Chinese proletariat has advanced in its revolutionary development during this period.

A comparison of the Canton rising with the July rising in Vienna unquestionably demands more caution in view of the enormous difference in the whole situation between Central Europe and China. But none the less this comparison is invited just because of the contrast in the character and conditions of the development of the workers’ movement in Austria and China, not to speak of the obligation on Marxism to regard both these events as parts of a single process of international revolution. The Viennese rising revealed all the rottenness and hopelessness of capitalist stabilisation in Europe. Therein consists its enormous historic and international significance. But from this point of view the Canton rising has no less significance. With the voice of cannon and shot it proclaimed to all the world the truth concerning the indestructible force of the Chinese revolution. For the Canton rising occurred after a triple defeat of the Chinese revolution (in Shanghai, in Wuhan, and around Swatow). For the revolutionary overthrow was carried out in the capital of the Kwangtung province, in which during the last eight months a most ferocious and bloody persecution has been waged against the working class and the peasantry. In this gigantic force of the revolutionary movement of the Chinese workers and peasants is contained a tremendous threat to all the world imperialism, and in the first place to British imperialism. If even Kuomintang revolutionary Canton could in its day strike such blows at British imperialism that its might in the east was seriously shaken, the rise of the workers’ and peasants’ revolution in southern China brings with it a much more terrible danger to the colonial dominion of Britain and other imperialist countries. This circumstance attaches a highly important international significance to the events in Canton.

Vienna and Canton.

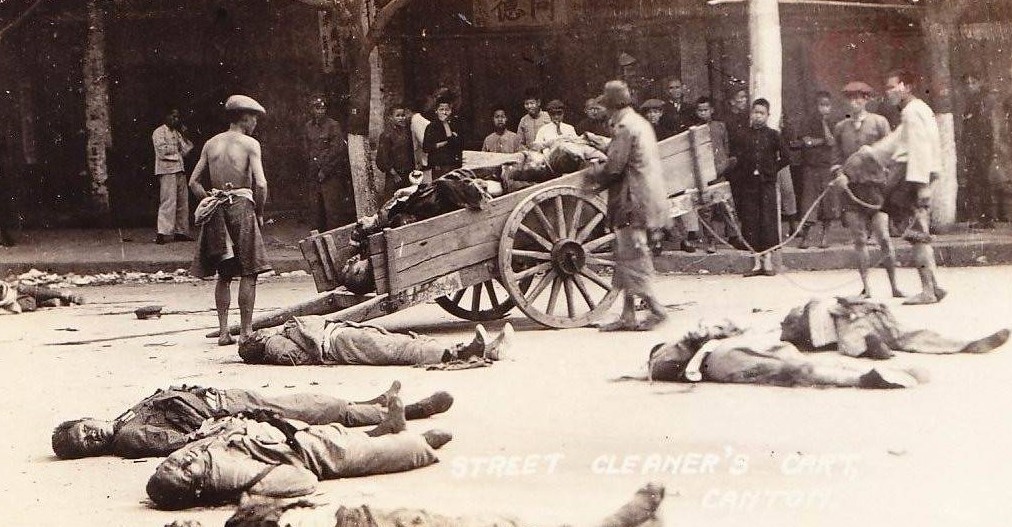

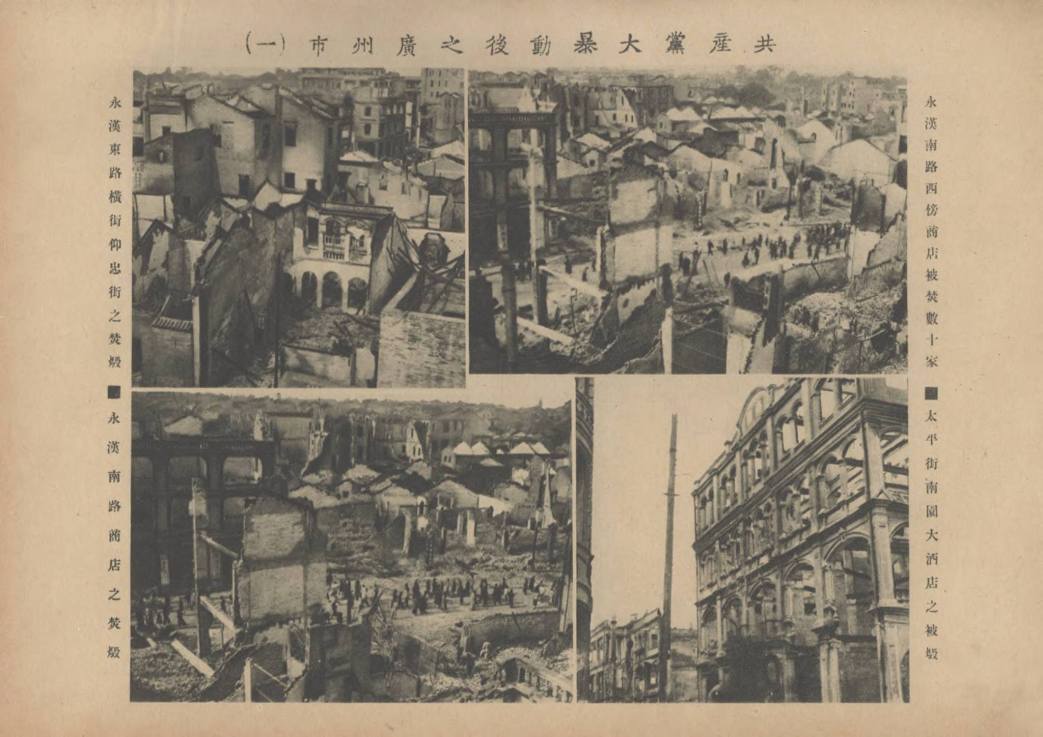

But if we compare the type of the workers’ risings in Vienna in July and in Canton in December last year, we must come to the conclusion that the Canton rising belongs to a much higher form of revolutionary class struggle than the demonstration of the Viennese proletariat. The rising in Vienna was an elemental, unorganised outburst of indignation, which had grown among the masses of the working class; by no one was it appointed and prepared; it did not set itself the conscious task of overthrowing the bourgeois government and the achievement of proletarian dictatorship; it did not succeed in growing to the extent of raising the slogan of Soviets; it was a gigantic explosion, swiftly dying away within a few days. The Communists self-denyingly fought in the front ranks on the streets of Vienna, but it was not they who led the elements, but the revolutionary elements which led them. Quite otherwise was the position in Canton. The Canton rising was prepared (politically, organisationally and technically) and carried out by the Chinese Communist Party. It pursued the conscious aim of dominating the bourgeois landowner reaction and the conquest of workers’ and peasants’ government. It began under the banner of the Soviets. It based itself on the elemental rise of the revolutionary movement of the worker and peasant masses, but it was organised. The conjunction of the elemental and the conscious- this it is that compels us to allocate the Canton rising to the higher forms of the proletariat’s class struggle. And finally, in distinction from the Viennese rising, the rising in Canton is not a swiftly passing explosion, but the signal and beginning of a new rise in the revolutionary struggle of the Chinese people. This last thesis may easily arouse doubts among those who do not see the distinguishing peculiar features of the Chinese revolution, those who do not take into account its singularities. Actually, if one comes to the Canton rising with a conventional measure, one has to draw the conclusion that following on the destruction of revolutionary Canton should succeed a long period of depression in the workers’ and peasants’ movement of China, as has always happened after serious defeats of the revolution in other countries. But from this point of view it is not possible to explain the very fact of insurrection in Canton. For the Canton rising broke out almost immediately following the heaviest defeats of the Chinese revolution. True the savage orgy of white terror now raging in Canton exceeds in its dimensions and ruthlessness all that the Chinese workers’ and peasants’ movement has ever had to experience before. But it must not be forgotten that after the perfidy of Chiang Kai Shek and the leaders of the Kuomintang in Wuhan the persecution of the revolutionary masses was also no joke. One can give some idea of its dimensions by the figures ascertained by I.C.W.P.A. of 29,000 workers and peasants killed during five months (from April to August) in only five provinces (including Kwantung). The counter-revolutionary coup in Shanghai and Wuhan, the dispersal of the armies of Ho Lung and Yeh Ting, the defeat of a number of peasant risings-all this gave more than one cause for international social-democracy and the mourners of the Trotskyist opposition to declare the Chinese revolution finished (Otto Bauer’s “1849”) or broken for a long period. How else if not as a mere coup must the Canton rising be regarded by social- democrats or persons holding the view that the Chinese Communist Party would ” go easily into Wang Ching Wei’s side-pocket”? But even in the ranks of Communists comrades are to be found disposed to draw the conclusion that “it was not necessary to resort to arms.” Victors are never condemned, but a rising which suffered such a serious lack of success involuntarily forces many to raise the question: but was a rising in Canton at the present moment expedient, was it not premature, would it not have been more correct for the Communists to occupy themselves with the preparation and collection of forces for a more serious attack? We consider it necessary to answer these questions with all clarity. It is necessary to do so because the answer to these questions should simultaneously elucidate a number of other more important problems: i.e., through what stage is the Chinese revolution passing at the present time and what should be the tactics of the Chinese Communists.

Was it a “Putsch”?

What reason is there for regarding the Canton rising as a coup? The fact that the revolutionary over- throw was not successful, that the insurgent worker Communists were destroyed within forty-eight hours? But if we are to judge only by this symptom, then one can declare all unsuccessful risings to be coups and ad- ventures, and there have been not a few such in the history of the revolutionary struggle of the international proletariat. The Moscow armed insurrection of 1905 lasted only a few days altogether and then was sup- pressed. The same can be said of the Hamburg rising of 1923. But Bolshevism never condemned the Moscow and Hamburg risings, never declared them to be coups. On the contrary, Bolshevism always regarded both these risings as typical examples of the proletariat’s revolutionary tactics. It is obvious that it is not permissible to draw conclusions as to the adventurist character of the rising itself, merely from the one fact of the defeat of the rising, no matter how great that defeat may be.

Were Conditions Ripe?

Were the objective prerequisites of an armed attack in Canton present? This question must necessarily be answered resolutely in the affirmative. The general situation in China bears an exceptionally tense, directly revolutionary character. No one can dispute that. The general crisis in China (both the economic and political and military crises in the country’s international situation) has reached the extreme limits of severity. How did Lenin define a revolutionary situation? “The impossibility of the ruling classes retaining their domination in an unchanged form; one or another crisis at the top, a crisis in the policy of the ruling classes, causing a fissure into which burst the dissatisfaction and indignation of the oppressed classes. To ensure an advance of revolution it is usually insufficient that the lower orders do not wish to, it is also necessary that the upper orders cannot go on living in the old fashion.” History has not known a clearer illustration of these words than the contemporary situation in China. On the ruins of the ancient Chinese despotism, on the fragments of the Asiatic-feudal State system, new local “formations of governments,” inimical to one another, devouring one an- other, arise and perish with kaleidoscopic rapidity. The bourgeois militarist reaction in the southern part of China was not only unable to arrest or restrain this process of disintegration and wrecking of the old social system, it even speeded up its tempo. The intensifying crisis among the bourgeois-landowner “upper orders” of China finds its expression in the unbroken internecine wars of various militarist groupings. The whole of southern China is in the grip of these generals’ wars at the present moment. And into this “fissure” has burst the indignation of the oppressed classes in the form of an endless series of peasants’ risings in the provinces and the attempt at a revolutionary overthrow in Canton itself.

Lenin’s second symptom of a revolutionary situation: “a more than usual increase in the severity of the need and poverty of the oppressed classes,” does not call for special elucidation to meet the case of China. We all know the extraordinarily low level of life, or rather of slow death, to which the working class, the peasantry and the town destitute class of China are condemned be- neath the oppression of foreign capital and under the domination of the landowners, the militarists and the “national” bourgeoisie. And finally, the third symptom of a revolutionary situation: “a large increase in the activity of the masses, who in the peaceful epoch calmly allow themselves to be despoiled, but in stormy times are drawn both by all the circumstances of the crisis, and by the upper orders themselves into an independent historic attack,” finds its expression in the continually increasing insurrectionary movement of the peasants and in the violent growth of the strike and political struggle of the town proletariat. This is true both in regard to all China, and in particular in regard to the Kwantung province. In this province the elemental revolutionary movement of the masses has grown with especial strength of recent months. In September the whole of the north-west of Kwantung was embraced by a gigantic blaze of peasant war. The revolutionary army of Ho Lung and Yeh Ting went to meet the peasant rising. As we know, it was broken up below Swatow (the causes of its defeat, which deserve special attention, lie mainly in the opportunistic errors of the Communists at the head of the army). Nor did the insurgent peasantry succeed in gaining a big victory. But the revolutionary movement of the peasantry was by no means completely broken up. Of Ho Lung’s and Yel Ting’s army two divisions were preserved and renamed the first and second workers-peasants’ divisions. Around these revolutionary sections the peasants’ movement again began to gather. Towards the beginning of December the second workers’-peasants’ division, opera- ting in the district of Hai-sin and Lu-fing, held eight counties. In these counties a Soviet Government was established for the first time during the revolution in China. The area of the peasant rising swiftly extended. During the last few days the telegraph has brought information of the seizure of a number of towns and county centres by the peasants. And at the same time to the south (on the island of Hainan) and to the west of Canton the government of the militarists has of recent months held on only in the towns. In the villages all the power is in the hands of the revolutionary divisions and the peasants’ unions. In October a wave of workers’ movement rose in Canton itself in response to the peasants’ rising. On the 14th December the revolutionary sailors’ union seized the building of the yellow trade union. The mercenary leaders of the yellow trade unions were executed by the workers in the street. In the steps of the sailors followed other revolutionary unions. For five days the class unions were masters of the situation in Canton. They won summary recognition of the legality and established themselves in their old quarters. Gigantic workers’ demonstrations were held in the town. At the demonstrations the Kuomintang banners were destroyed and the workers marched through the streets of Canton under Soviet banners and the Red Army star. Li Chai Sung quickly succeeded in driving the revolutionary unions back underground. But the workers’ movement continued as active as before. On October 7th all the printing workers in Canton went on strike an incident which occurred on the Tenth Anniversary of October only in China, only in Canton. After Chang Fat Kwai’s overthrow of Li Chai Sung and seizure of power, the workers’ life in Canton began to beat at a specially violent tempo. Summary meetings and demonstrations were being arranged continuously, directed against both Li Chai Sung and Chang Fat Kwai. The latter’s coquetting with the workers met with splendid revolutionary resistance. After his error in counting on the support of the workers Chang Fat Kwai turned to bloody repression. This caused the Canton workers cup of endurance to overflow. The masses were itching for the fight, the masses raised the question of revolt. In these circumstances the Chinese Communist Party organised armed insurrection in Canton.

There can be no question whatever that the moment of revolt in Canton coincided with the highest point of the rise both of the workers’ and of the peasants’ movement throughout the Kwantung province. Not only that, but it coincided with an extreme intensification of the crisis among the “upper orders”; only a few days before the rising Chang Fat Kwai had had to remove a large part of his soldiers from Canton in order to organise resistance to Li Chai Sung’s divisions which were marching on the town. The few regiments of Chang Fat Kwai left in Canton were to a large extent “disorganised” by Communist activity, which had been carried on in their ranks over several months. There was a full guarantee that some of these regiments would come out on the side of the insurgent workers. It was impossible to await a more favourable moment for armed insurrection. The Communists absolutely correctly estimated the decisive moment for striking a blow at the antagonist.

The Revolutionary Spirit of the Chinese Workers.

Such were the objective pre-requisites of the Canton rising. But we know that objective pre-requisites alone are insufficient for assuring victory to the revolution; it is also indispensable that there should be present “the capability of the revolutionary class for revolutionary mass action sufficiently powerful to break the old government, which never, not even in the period of crises, falls if it be not thrown down.” (Lenin.) And what was the position in regard to this factor of insurrection in Canton? Of the capability of the Chinese proletariat ‘for revolutionary mass action” hardly any except in- corrigible Mensheviks can doubt. Nor can there be any doubt that the Canton rising based itself directly on a rise of the mass movement and was an attack of the masses themselves. The whole problem consists in whether the advance guard of the Chinese proletariat- the Communist Party- was capable of organising, heading, and triumphantly effecting a revolutionary overthrow. We know the gigantic load of Menshevik errors in the past with which the Chinese Communist Party came to the Canton rising. But within a short time the Party was able to correct and overcome those errors. The best test of this is the line which the Party has been following of recent months in the same province of Kwantung. After the defeat of Ho Lung’s and Yeh Ting’s army the Communists betook themselves to revolutionary work among the peasants with doubled and tripled energy. The gigantic dimensions of the peasant movement quite recently in Kwantung is in large measure due to this work of the Chinese Communist Party, to its guiding participation in all the mass advances of the peasantry. But what of the position taken up by the Party in the day of Chang Fat Kwai’s coup? It would have done honour to any large European Communist Party. The Chinese Communist Party foresaw Chang Fat Kwai’s coup, had already evaluated its counter-revolutionary character and succeeded in maintaining to the end an irreconcilably hostile attitude to this “left” general. And yet Chang Fat Kwai came out under a banner and slogans which were more radical” than the banner of Pilsudski in his time. And we can get an idea of the correct line taken up by the Chinese Communist Party even from the slogans as passed on to us by the imperialist agencies.

Justification of the Rising.

Thus the combination of objective and subjective factors historically justifies the revolutionary rising in Canton and makes it absolutely in accordance with law, and even inevitable. It is just because of this that we regard it as an enormous factor in not only the Chinese, but also the international revolutionary movement, despite all the heaviness of its defeat. What are the further prospects of the revolutionary struggle in China? We have no desire whatever fatalistically to affirm that such defeats as that in Canton will not weaken the revolutionary mass movement of China in the least degree. No, the lesson conveyed by the defeat is enormous, and the healing of the bloody wounds received in Canton will occupy the Chinese workers and peasants a long time yet. But we maintain that this defeat will not arrest, or rather, cannot for any serious length of time arrest the new rise of the Chinese revolution which has begun. On what do we base this statement? Not simply on “faith” in the invincibility of the Chinese revolution, but on the circumstance that any other road except the revolutionary one would not be able to avoid or to alleviate or weaken those contradictions which brought to birth and are now nourishing the great Chinese revolution. There is no class, there is no social force in China which could direct the development of China along the way of compromise and reformism. This is excluded both by the entire international and the entire internal situation in which China exists. The Chinese “national” bourgeoisie have shown themselves to be just as incapable (if not more so) as the old ruling classes of China, of resolving the historical tasks which have arisen before this great country. It is too immature, too weak, to do so.

A New Stage.

The victory of the bourgeois-capitalist reaction in Canton cannot interrupt or arrest the revolutionary development of China just because reaction increases and develops to the extreme degree of intensification those contradictions which are causing the breakdown of the present-day economic system of China. All talk of the possibility of a “Prussian” or “Stolypin” road of development in China at the present time is based upon an absolutely superficial attitude, on fictitious analogies, and is radically off the track politically. The difficulties are great, but the workers’ and peasants’ revolution will succeed in overcoming them. China is entering upon a period of development and intensification of extremely ruthless civil war. Ahead lie fresh gigantic struggles and conflicts. The Canton rising is only the beginning of a new stage.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-5/v05-n02-jan-15-1928-CI-grn-riaz.pdf