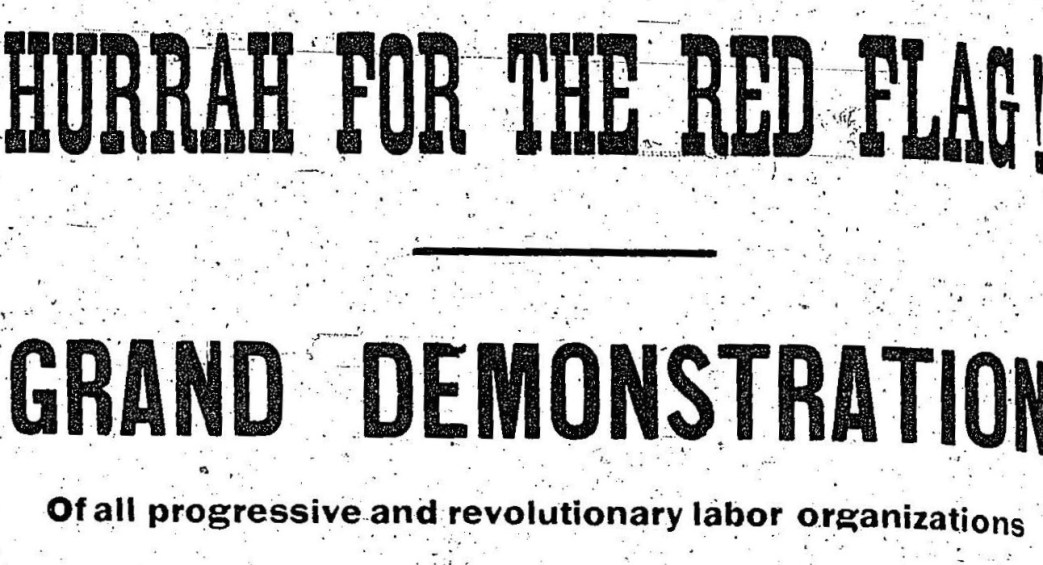

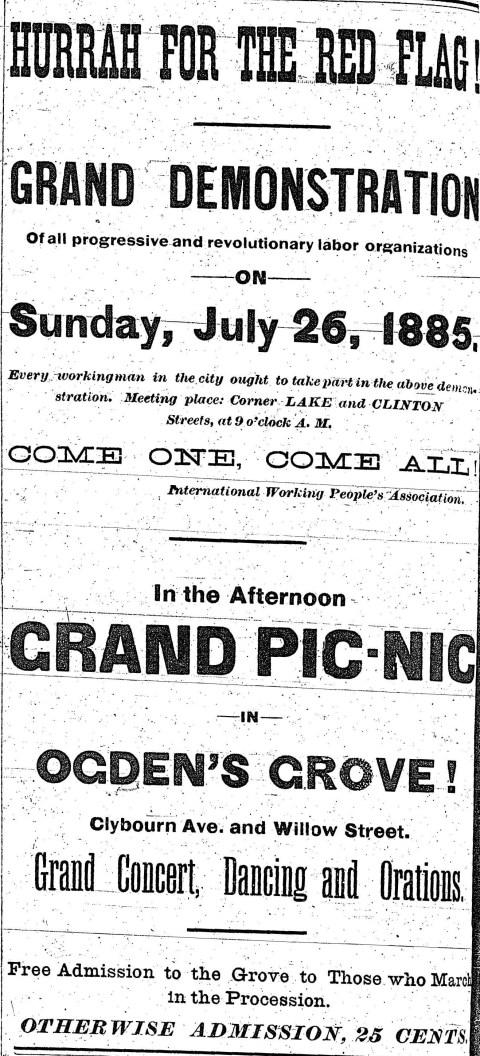

‘Brave Marching Women Guard Red Banner’ from The Alarm (Chicago). Vol. 2 No. 1. August 22, 1885.

In the grand demonstration of July 26. there were seven ladies who marched with the American Group, as guard to a beautiful banner. It was a thing unique and must have suggested to the thousands of spectators on that bright Sunday morning that if Communism can attract the gentler sex to such a degree that they will take part in public demonstrations, and in obedience to their convictions dare even to face public scorn and the possibility of disorder and arrest by the organized powers of society, there surely must be some quality in Communism which challenges respect. The most of them are mothers, who, by all, the usual experiences, have been taught to know the meaning of the words distress and care; they know the value of sweet peace, whose consolation they have tasted in scant measure; yet, out of a sincere desire for a full share of contentment, they engage in a cause which to the unreflecting mind has a significance only of confusion and barbaric strife. The mere parade in the sense of pageantry was of subordinate interest to them; the effect aimed at was an impression upon the public mind to disprove the idea that Anarchists are creatures of the baser sort- rough, disorderly, animated by the impulse of destruction for plunder’s sake alone, and at war with the best interests of society. No one could view those ladies as they marched, and especially could no one meet them in exchange of ideas in conversation, without being convinced that their presence before the public eye was due to an intelligent conviction of the truth of communism. They sought to win respect for the truth they hold by showing their personal devotion for it, and comments upon their appearance have shown a gratifying proof that the design was met by complete success. Conduct such as this has a very important influence in the propagation of any cause that has a basis of ideas.

The act was heroic. It had the flavor of devotion derived not alone from merit in the argument, but also from its likeness to the many acts of bravery by women recorded in history. The thrill of admiration that comes to the student upon perusal of them in the books of to-day will be felt by future generations poring over the record of events of these times which are at the dawn of the anarchistic period. The ladies are of course above the influence of a wish to grace the procession for historical vaniglory- their purpose was loftier and more earnest, and a practical effect was sought for the advancement of an argument; but none the less will history find itself in debt to them and acknowledge the debt in graceful mention. No feature of the parade could have made a stronger impression upon observers than this. It was the touch of delicacy that gave refinement to the demonstration, and disarmed much criticism which might have found a target in masculine members. Even the most ignorant of the minds that are opposed to us must have been affected by the thought that a cause having such exponents is not likely to be wholly bad. This impression alone may be counted a large gain for us in the work of spreading anarchistic ideas; but we are confident that, with almost every one who looked on our line of march, the reflection could not be resisted that it was the ability to reason, the use of reason, and the deductions from reason which inspired those delicate women to step forward confessed as revolutionists, and bear the fatigue of a parade under the red flag.

We may consider the ice now fully broken, and future demonstrations of all anarchistic groups will probably have within them this very striking feature. The amount of argument contained in the fact of women showing themselves to be our companions in this work of humanity is greater than can be readily estimated. It has a wonderful power to propitiate the ignorant prejudice of the multitude, while to higher but still objecting minds it argues a less degree of blood- thirstyness and piracy than is generally credited to us. In all ways it is to our advantage, and the grand project for human equality could scarcely find a more efficient means of compelling the respect and attracting the sympathy of our fellow members in society.

J. A. H.

The Alarm was an extremely important paper at a momentous moment in the history of the US and international workers’ movement. The Alarm was the paper of the International Working People’s Association produced weekly in Chicago and edited by Albert Parsons. The IWPA was formed by anarchists and social revolutionists who left the Socialist Labor Party in 1883 led by Johann Most who had recently arrived in the States. The SLP was then dominated by German-speaking Lassalleans focused on electoral work, and a smaller group of Marxists largely focused on craft unions. In the immigrant slums of proletarian Chicago, neither were as appealing as the city’s Lehr-und-Wehr Vereine (Education and Defense Societies) which armed and trained themselves for the class war. With 5000 members by the mid-1880s, the IWPA quickly far outgrew the SLP, and signified the larger dominance of anarchism on radical thought in that decade. The Alarm first appeared on October 4, 1884, one of eight IWPA papers that formed, but the only one in English. Parsons was formerly the assistant-editor of the SLP’s ‘People’ newspaper and a pioneer member of the American Typographical Union. By early 1886 Alarm claimed a run of 3000, while the other Chicago IWPA papers, the daily German Arbeiter-Zeitung (Workers’ Newspaper) edited by August Spies and weeklies Der Vorbote (The Harbinger) had between 7-8000 each, while the weekly Der Fackel (The Torch) ran 12000 copies an issue. A Czech-language weekly Budoucnost (The Future) was also produced. Parsons, assisted by Lizzie Holmes and his wife Lucy Parsons, issued a militant working-class paper. The Alarm was incendiary in its language, literally. Along with openly advocating the use of force, The Alarm published bomb-making instructions. Suppressed immediately after May 4, 1886, the last issue edited by Parson was April 24. On November 5, 1887, one week before Parson’s execution, The Alarm was relaunched by Dyer Lum but only lasted half a year. Restarted again in 1888, The Alarm finally ended in February 1889. The Alarm is a crucial resource to understanding the rise of anarchism in the US and the world of Haymarket and one of the most radical eras in US working class history.

PDF of full issue: https://dds.crl.edu/item/54013