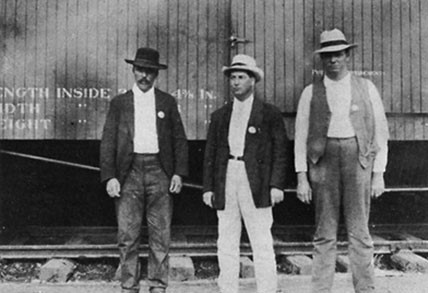

On November 22, 1919 Saul Dacus, Black lumber union organizer, walked down the main street of Bogalusa, Louisiana flanked for protection by two armed white men; union carpenters Daniel O’Rourke and J.P. Bouchillon. Murder ensued. Ten years after the fact, legendary radical labor journalist Art Shields gets the inside story of the ‘Bogalusa Massacre’ and the heroic multi-racial defense of southern timer workers.

‘Heroes of Southern Timber’ by Art Shields from Labor Defender. Vol. 4 No. 10. October, 1929.

LUM WILLIAMS was a labor hero. His fellow workers said after the Bogalusa massacre: “He died doing his duty. There was not enough money to buy him nor enough guns to scare him.”

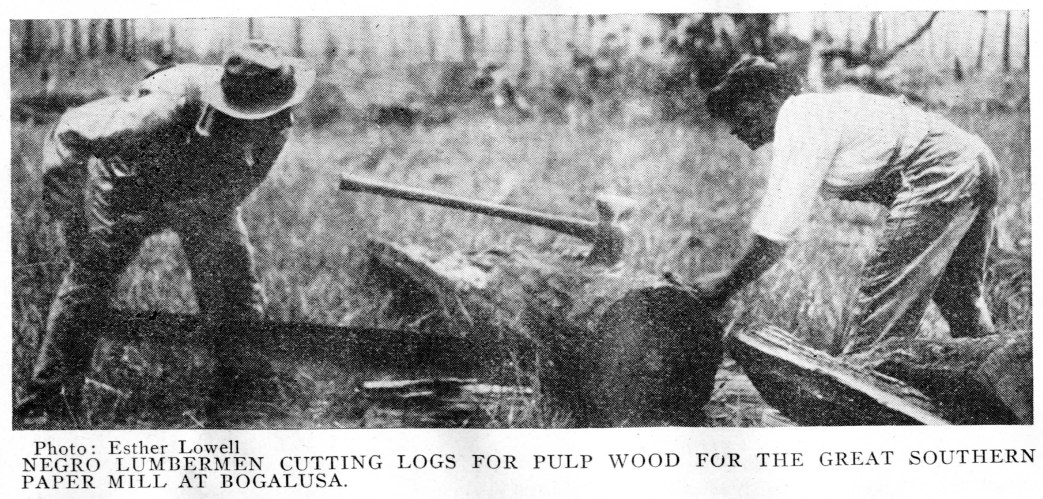

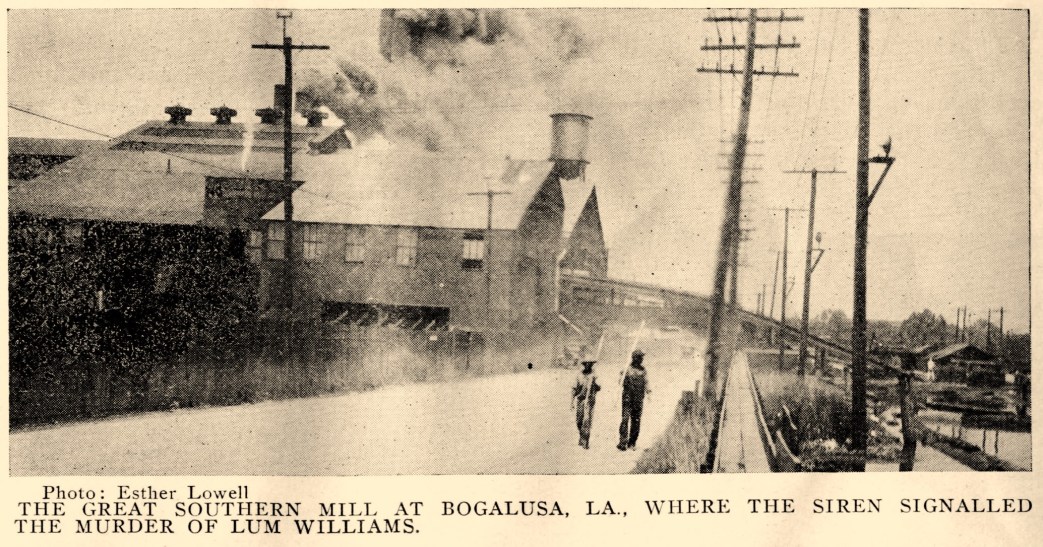

It is almost 10 years since the massacre. November 1919 was a bloody month for the lumber workers in the red fir and cedar forests of the northwest and the piney woods of the south. The big timber companies loosed their gunmen and used the American Legion against the unions with Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer helping the pack. On November 11 they raided the loggers’ hall in Centralia, Wash., castrated and lynched Wesley Everest. Eleven days later they slaughtered Lum Williams and four other sawmill workers by Pearl River in Louisiana, nearly 3,000 miles away. Lum Williams had lived in Bogalusa 12 years and was a millwright in the Great Southern Lumber Company mill when the 1919 wage-cuts came. Williams led the union movement that enrolled nearly a thousand men in the biggest sawmill in the world.

Bogalusa was a shabby lumber city of about 10,000, with cheap dwelling houses and great industrial plants belching smoke. An unusual setting for a diplomat, perhaps, but the diplomat was here, one of the shrewdest that ever mixed handshakes with bullets. Col. Sullivan, the clever general manager of the Great Southern saw Williams was a key man that he should win to his side. Failing in that he offered the young millwright $2,500 to leave town quietly. Williams refused.

So, quite coolly, Col. Sullivan passed sentence of death. If Williams stayed he would be killed, went the word. No idle threat. Bogalusa gunmen had a record of murders that Butte, Montana, must step to equal. A reign of terror was going on that Fall. Just a few days before the massacre the gunmen went through the Negro quarter whipping union members. One old Negro had both arms and one leg broken. Ed O’Brien, white, vice-president of the trades council, and old northwesterner, was run out of town by Banker Lindsley’s Self-Preservation and Loyalty League, with the letters “I.W.W.” painted on his back, though O’Brien was an A.F. of L. man. The gangsters accused him of expressing sympathy for the Centralia prisoners.

Williams had everything to live for. He had a beautiful wife and child. But he was game and devoted. He would not run away. However, he wired the governor of Louisiana and Attorney General Palmer demanding protection. Palmer was just then arresting steel He strikers and deporting revolutionists. coldly wired Williams that the United States His New government would not interfere. Orleans Bureau chief of the department of justice, Forrest Pendleton, made a brief visit to Bogalusa and conducted a fake investigation, winked his eyes at the approaching massacre and went home. Don’t forget that fellow Pendleton, readers. He later opened up a strikebreaking private detective agency of his own in New Orleans and during the street car strike there this summer bore the title of chief U.S. deputy marshall.

Then came the episode of Sol Dacus that inflamed the gunmen to the breaking point. Dacus was the Negro organizer who had been operating in the woods among the loggers in the camps outside of the sawmill town. The gunmen had been after him but Sol was clever.

He shifted his base, sleeping on a bed of pine needles under the trees one night and in some lonely Negro worker’s cabin the next. Then one day he appeared openly in Bogalusa, walking down Columbia Street to Williams’ headquarters.

Two white union men with shotguns in their arms walked beside Dacus, guarding their colored fellow worker. They brought him to Williams’ office where he held a consultation with his chief. At once the Great Southern gang raised the stereotyped slogan of “race equality” throughout Bogalusa. And privately they whispered: That man must die quickly.

Williams could whip two gunmen but not 75, the approximate number Col. Sullivan sent against him. The mill siren shrieked the signal at high noon Saturday. The gang gathered, a motley crew of roughnecks and white collars. Some were under Sullivan’ orders as company gunmen. Some as city policemen, for Sullivan was mayor as well as general manager. And many belonged to the company’s Loyalty League, led by Banker Lindsley. They rushed at the Williams’ place on Columbia Street, the main thoroughfare. The millwright’s family was in the cottage on the lot. Tom Gaines, a militant unionist soon to die, was in the garage. There was an old boat in the yard and the tiny union office where Williams was sitting with his brother Jim and a group of unionists.

Let E.C. Rowan tell the story of the slaying in his own vivid way. Rowan was an idealistic ex-foreman of the company who fought for the union all through the campaign. I’m taking the following account from the pamphlet he wrote of the massacre. His narrative is the only authentic story of this historic affair, and I am indebted to W.L. Donnels, an organizer who risked his life in Bogalusa, for what may be the only extant copy. It comes to Labor Defender readers. now for the first time I am sure, since its distribution 10 years ago was very limited and confined to southerners.

Rowan’s story follows as he got it from the survivors: “Jim Williams said to Lum Williams, ‘Here comes that bunch for something.’ Lum answered, ‘Well, let them come, we’ll see what they want.”

“About twenty-five of the gunmen came in with shot guns near their shoulders. They ranged themselves between the dwelling and the office, about 15 feet from the office. Several other men with guns stopped near the boat. Without rising from his seat, Lum said:

“Come on in you fellows and let’s see what you’ve got.’

“Lum then walked to the door unarmed and said:

“Well, here I am, what do you want?’

“The head gunman had been pointing his gun toward the garage, where he had probably seen Tom Gaines. As Lum spoke the gun was turned towards him, and he was shot; the load hardly scattered. It tore a hole through him about as big as man’s fist, touching his heart.

“Williams fell without a word. Bourgeois, his brother-in-law, caught him and was dragged down under him.

“Bourgeois says that Lum looked toward him and smiled as sweetly as he ever saw; he died doing his duty. There was not enough money to buy him, nor enough guns to scare him.

“When Lum was shot, every man in the mob seemed to shoot. Then Bouchillon was shot in the stomach with a shotgun, also in the right hip with a rifle. He too fell on top of Bourgeois.

“Tom Gaines in the garage was also killed instantly, a buckshot load under his left arm.

“The other men crouched in the office, or got behind the door. It kept raining bullets. The glass of the door spattered in their faces. Jim Williams said, ‘We must do something or all of us will be killed.’ He grabbed a 22 calibre target rifle, and shot Jules LeBlanc in the wrist. This shot surprised the gunmen so that many of them tried to get behind the house and the boat. The firing almost ceased.

“Jim Williams, Richoux and O’Rourke jumped through the window into the other lot. O’Rourke had already been given his death wound. He threw up his hands and begged not to be shot again. Clay Richoux was wounded, but got away, leaving a trail of blood. Jim Williams had left the empty rifle in the house. He threw up his hands. A man attempted to shoot him, but Mrs. Williams, Jim’s wife, struck the gun: the man slapped her down. Lum Williams’ wife then struck the gun, and the load of buckshot hit the fence nearby.

“After getting to the street O’Rourke was jerked into an automobile by officials of the Great Southern Lumber Co. O’Rourke was carried to the Great Southern Lumber Co.’s hospital under arrest, and died there a few days later.” (O’Rourke was in effect murdered in the company hospital, it is said. Good treatment would have saved him.)

“Four widows and sixteen orphans are left at the mercy of the world.

“That night at the Pine Tree Inn a banquet was given. This was almost in hearing of the moans of the families of Lum Williams and of his father. The banquet was attended by many of those who had fought so galantly in this battle.”

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Not only were these among the most successful campaigns by Communists, they were among the most important of the period and the urgency and activity is duly reflected in its pages. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1929/v04n10-oct-1929-ORIG-LD.pdf