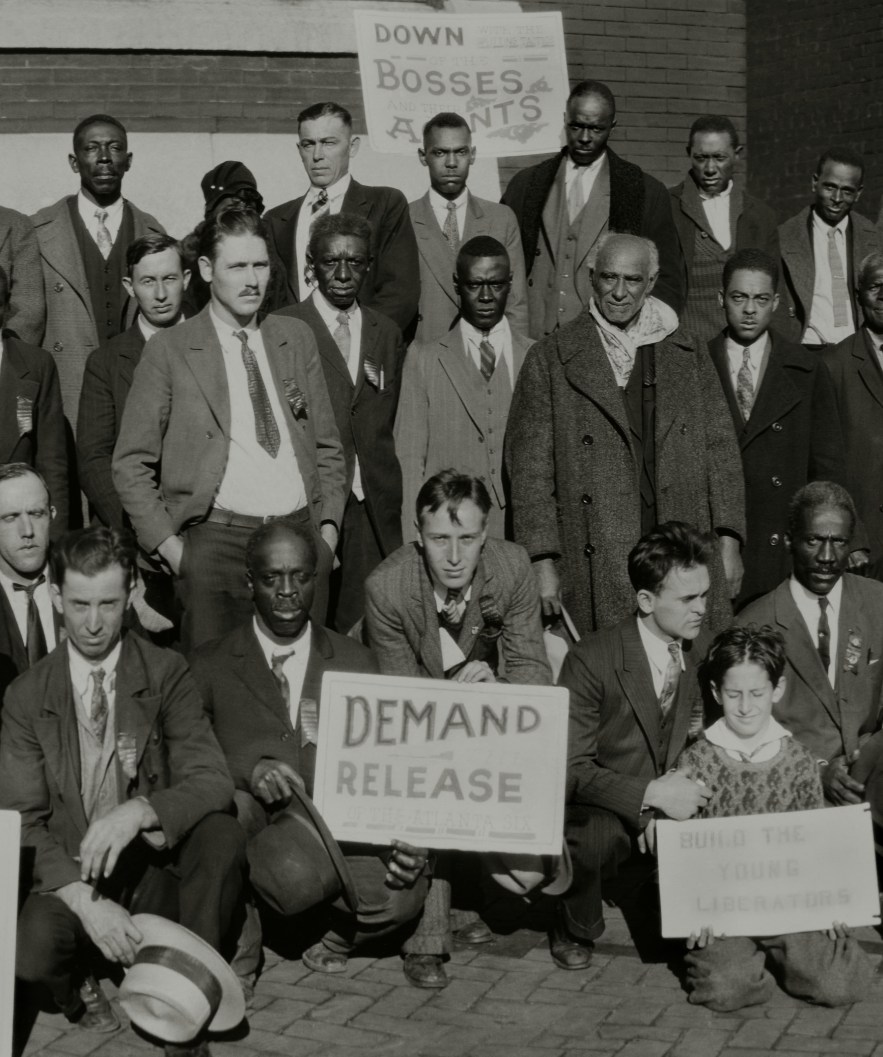

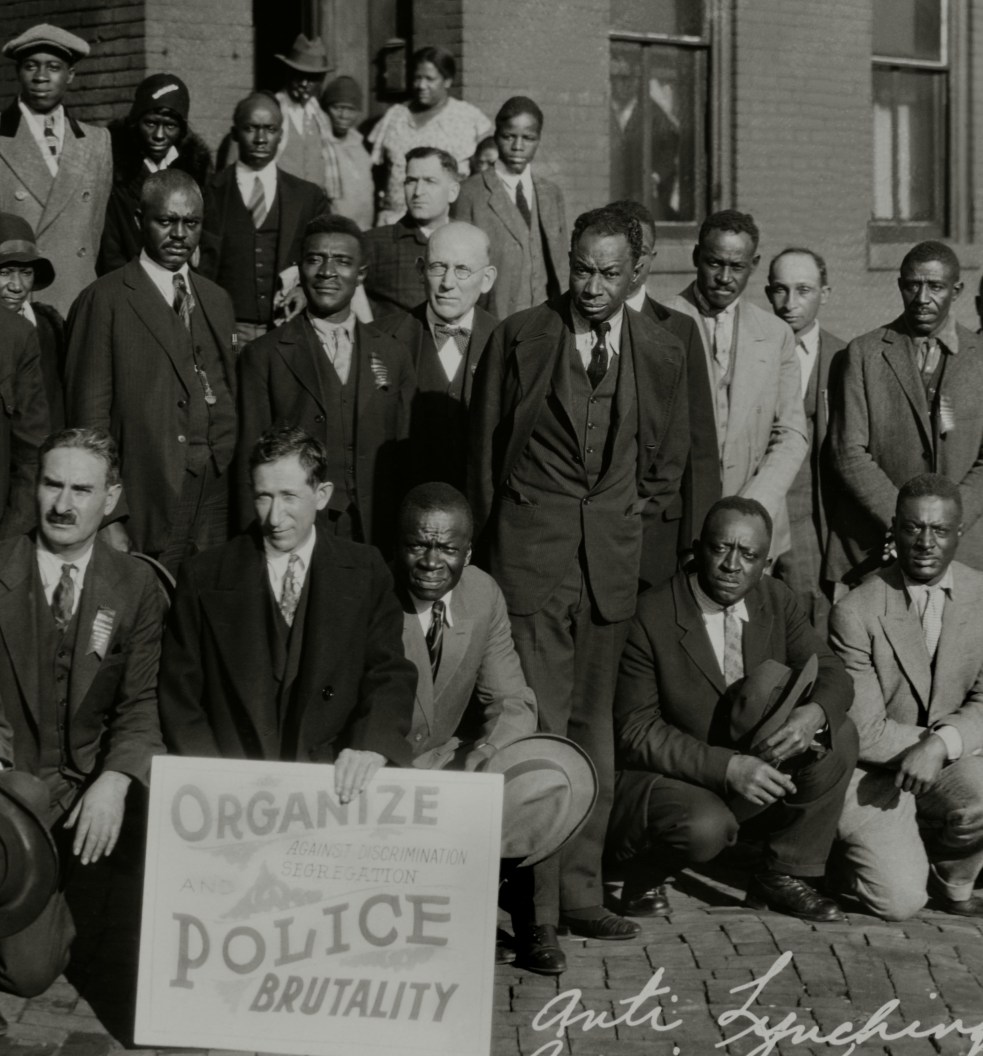

Cyril V. Briggs report, serialized over three issues, on the Emergency National Convention Against Lynching in St. Louis during November, 1930. Over 100 delegates who would found the League of Struggle for Negro Rights. Illustrated with a remarkably detailed photo from the convention of those delegates.

‘St. Louis Convention of the League of Struggle for Negro Rights’ by Cyril V. Briggs from the Daily Worker. Vol. 7. Nos. 280-282. November 22-25, 1930.

ST. LOUIS, MO.-There have been several fine conventions of class struggle organizations during the past year- the Trade Union Unity League convention in Cleveland, the convention of the International Labor Defense in Pittsburgh, etc. None has shown a more militant spirit or a finer representation of workers from the factories and fields than the convention just ended of the American Negro Labor Congress, whose name is now by unanimous decision of the convention the League of Struggle for Negro Rights.

One hundred and twenty delegates were present, a number of them arriving late Sunday. They came from 18 states, and from as far away as California, Alabama, New York. They represented 17 organizations in addition to the local branches of the League of Struggle for Negro Rights. Seventy-three of the delegates were Negro workers; forty-seven, white workers. There was a women representation of 17, most of them Negro women from the South and the Middle West. There were 25 young worker delegates, some of them members of the Young Liberators, the youth organization of the League of Struggle for Negro Rights.

The spirit of the delegates was expressed not only in their enthusiasm and militancy in the convention but by the grim determination by which they overcame every obstacle arising out of their wretched economic conditions as a result of their exploitation by the white ruling class and of the efforts of the bosses and their state agents to prevent them going to the convention. Some came by old Fords which broke down many times on the way. Others arrived by buses.

Several rode the rods part of the way. One young Negro worker from Birmingham traveled by freight to Chattanooga where he attended the Southern Anti-Lynching Conference and was elected a delegate to the St. Louis convention. He was told by his father that he need not return if he “mixed himself up” with the anti- lynching convention. He made the most militant speech at the Chattanooga conference, expressing the readiness of the southern Negro masses, and especially the youth elements, for militant struggle against boss oppression. He arrived in St. Louis penniless, but militant and happy to be a part of a convention organizing a real struggle against the savage oppression to which his race is subjected. Another Negro young worker rode the rods into St. Louis from Youngstown, Ohio. Most of them starved on the way, being barred from eating in the white lunchrooms, and not always able to go out of their way to the Negro sections, which are always segregated away from the main streets of the towns. The white delegates suffered along with the Negro delegates, walking out of the white lunchrooms in company with the Negro delegates when the latter were refused service. In one town in Ohio, a delegation of Negro and white workers traveling by Ford was held up by police at the point of a gun and forced to submit to a search of their persons for no other reason than that they were white and Negro workers traveling together.

The most militant speeches were made by the southern Negro delegates during the discussion from the floor. Mary Pevey from Georgia electrified the convention with her bitter indictment of the capitalist oppressors of Negro and white workers, declaring that “not only the Negroes are being oppressed but the workers everywhere are being brutally exploited and thrown on the streets to starve during the present crisis of capitalism. The conditions concern not only one race of people but all the workers. We say that if a worker cannot get a living wage- they are not free; they are slaves. It is our duty to tell you that the preachers will tell you when you return to your homes to pray these conditions away, but we cannot pray these conditions away. We have got to organize, white and Negro, side by side, against our common enemies. We must be willing to die if necessary for the cause.

A Negro delegate from Indianapolis was so thrilled by the fighting spirit of the convention that he wished its proceedings could be broadcasted to all the workers throughout the world. He told the convention how he had joined the church, he had joined the fraternal bodies, he had joined all sorts of reformist organizations, and never until he joined the League of Struggle for Negro Rights did he find an organization really fighting for the rights of the Negro masses. “My people are being lynched and these churches, lodges, etc., are not raising a hand to fight the lynching mobs. I am here with you to live and die in this struggle for Negro rights.”

Delegate Kingston from Philadelphia declared that “the working class today, both white and Negro, are faced with a problem that we must either submit to slavery and starvation, or combine our forces to combat them. We must stand together. The capitalists are able to maintain their rule only by creating a division in the ranks of labor. We must organize to fight.”

It is the unanimous verdict of the delegates to the anti-lynching convention of the American Negro Labor Congress (now the League of Struggle for Negro Rights) that history was made in this city during the past few days. It is a verdict that the imperialist oppressors of the Negro masses will be forced to concur in sooner or later.

The convention concretized the struggle of the Negro masses for unconditional equality, for the right of self-determination and by its decisions and its selection of the new name the League of Struggle for Negro Rights fully crystalized the idea that it is an organization of struggle and that struggle is for Negro rights from the very smallest fight against oppression and for all immediate demands of the Negro masses clear up to the ultimate liberation of the Negro masses, with state unity of the “Black Belt” and the right of the Negroes to decide their relationship to other governments with the right of separation from the bourgeois United States government if they so desire.

In a ringing manifesto to the Negro and white workers and poor farmers, the convention gave a bitter incident of American bourgeois democracy, pointing out that:

“In this so-called democratic United States, the citadel of capitalist civilization and culture, the white ruling classes carry out the most shameless and barbarous oppression of millions of Negro workers and farmers. Economically super-exploited, socially ostracized, in many places denied even the most elementary human rights, the Negroes are relegated to the lowest rungs of the social ladder and exist as a nation of “untouchable” or “social lepers,” subjected to the most flagrant persecutions and abuses.

“It is an infamous lie perpetrated only by a government of slave drivers and their agents to maintain the yoke of slavery has been listed from the Negroes in these United States. The so-called “proclamation of emancipation” only signifies a formal abolition of slavery without removing its real basis-the monopoly of the land by the plantation owners of the South, a monopoly they still enjoy-after the civil war- with the connivance and support of the so-called friends of the Negroes, the northern capitalists.

The fact is that in the South millions of Negro workers and poor farmers are still in the position in many instances worse than chattel slavery.”

The manifesto declares that the right of self-determination with confiscation of the land for the Negroes who work it is the only solution of lynching and Negro oppression and calls upon the white and Negro masses “to fight for the right of self-determination of the Negroes in the ‘black belt’ where they are the majority of the population by securing the land to the Negroes who work the land, by establishing the state unity of the Black Belt and by securing to the Negro majority the right and possibility of deciding its relations to other governments.”

It calls for “the removal of all armed forces of the white ruling class from this territory- in the Black Belt.” It declares that “in contradiction to the fallacy of the ‘peaceful’ return to Africa, this convention declares its determination to struggle for the unqualified rights of the Negroes in this country” and that further “in contradiction to the illusions spread by Garveyism, of revolutionary granting by the imperialists of freedom without struggle for the African masses, this convention supports the revolutionary struggles of the masses of the various African colonies against the imperialist robbers and for the establishment of independent native republics.”

The manifesto points out to the Negro workers that they cannot free themselves by merely fleeing to the North. “The heritage of the plantations still cling to them in the northern industrial centers. The chains of the convict labor in the South extend to the cities and enshackle the Negro industrial worker. The Negro in the North cannot free himself as long as his brother remains a slave in the South.”

It calls upon the white workers and poor farmers to support the struggles of the Negro masses, pointing out that “the interests of the great masses of white workers are diametrically opposed to any special oppression of any section of the working class. The existence of a section of workers specially exploited and oppressed is a constant threat to the living standards of the working class as a whole. The presence of cheap labor is a weapon with which the bosses are able to nullify all the economic gain of the workers. The poisonous venom of race hatred injected into the ranks of the white workers becomes converted into an instrument for the destruction of working class solidarity, the only guarantee for successful struggles.”

The manifesto was thunderously received by the convention and unanimously adopted. Both the delegates and the large number of spectators present were electrified with its militant demands, especially the demand for confiscation of the land of the Southern land-monopolists in the Black Belt for the Negro toilers who work the land and who today are shamelessly robbed and oppressed by the land owners.

THE adoption of a new and more appropriate name with a looser form of organization was not one of the least of the problems which faced the convention of the American Negro Labor Congress at St. Louis. The new name adopted is the League of Struggle for Negro Rights.

Since its organization in 1925, there had been objections to the name American Negro Labor Congress, some legitimate. some unfounded. While the new name has not disposed of all objections, it was nevertheless the considered opinion of the convention that the name League of Struggle for Negro Rights more adequately expressed the scope and purpose of the organization than had the old name or for that matter any other name proposed. The convention was unanimous in its adoption of the new name.

It is manifestly impossible to get into a name all the ideas behind an organization. The League of Struggle for Negro Rights expresses the main ideas of the purpose of the organization and that it is based on struggle and not on reformism and legalistic petitions like those organizations dominated by the belly-crawling petty bourgeoisie. Moreover, the name itself stresses the important lesson that struggle is essential to the securing of Negro rights, to the achievement of Negro liberation. The new name further removes the misconception that the league is confined to Negro membership alone or that its activities are limited to the confines of purely economic struggles. The fact that over one-third of the delegates to the convention were white workers, and that a number of them were elected to the National Executive Committee, gave unmistakable emphasis to the character of the league as an organization of white and Negro workers banded together in the struggle for Negro rights. Words like worker and labor were deliberately omitted from the new name. The convention did not intend that membership in the League of Struggle for Negro Rights should be confined to Negroes, nor yet to the industrial proletariat, Negro and white. The convention intended to draw into the struggle for Negro rights the broad masses, white and Negro, the farmers and agricultural laborers, and even those elements of the petty bourgeoisie who while not willing to support the economic struggles of the workers and poor farmers could yet be won on a nationalistic basis for the struggle for the right of self-determination, state unity of the Negro masses in the Black Belt.

By omitting terms like labor and worker from the new name of the organization the convention also gave notice of its intention not to confine its struggles for Negro rights to the field of labor. By designing its purpose as a struggle for Negro rights and not only ultimate Negro liberation, the convention rightly interpreted that struggle as including the very smallest fight against oppression and for all immediate demands clear up to complete Negro liberation.

The convention also decided that the organization should have a looser form than in the past. It is now possible for the masses to join the League of Struggle for Negro Rights in any form they desire, through affiliations of their lodges, clubs, unions, etc., or by joining a branch of the League. They can join any of the existent branches or they can organize a branch with six or more members, without regard to the existence of branches in any city. That is, they can organize as many branches in any city as suits their convenience. Each branch elects a small executive committee to direct the work. Each branch and affiliated organization elects a delegate to the City Committee.

In this way the convention laid the basis for the building of a real mass organization and for the prosecution of a militant struggle against Negro oppression and for the unconditional equal rights of the Negroes.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924. National and City (New York and environs) editions exist.