‘Conditions in the Restaurant Industry’ by Charles Mundell from One Big Union Monthly. Vol. 1 No. 8. October, 1918.

Why did the Hotel, Restaurant and Domestic Workers of Chicago recently attempt to organize themselves into a union, and why did the employees of the downtown lunch rooms recently attempt to pull a strike? What have these workers got to complain of? Do they not receive fair wages, to say nothing of the fact that they always get their three square meals each day?

These were the questions which I put to Mrs. ——, one of the active workers in the organization of this union and who was arrested and kept in jail three days. This fellow worker has been working in hotels and restaurants off and on for nearly three years. She knows whereof she speaks, having actually seen the conditions which she describes.

Fellow Worker first entered the employ of Mr. Weeghman, in one of the downtown lunch rooms. She describes the conditions which prevailed there at that time as positively heartbreaking. The wage received at that time varied from $8 to $9 and $10 per week for eleven, twelve and thirteen hours’ work per day seven days per week.

The conditions imposed upon the female help were especially revolting, she says. These girls were driven like slaves and worked for every ounce of energy in their bodies. Many times, she says, these girls would burst into fits of hysterical weeping because of the severe trials which they were compelled to undergo.

Not only were they expected to work like dogs, but they were given absolutely no protection against the liberties taken with their persons by their fellow employees. They were supposed to take as a matter of course the insults, the suggestions, and the vulgarity used by the men who worked alongside them. When they complained they were told that if they did not like it they could go. When asked by Fellow Worker why they submitted to these intolerable conditions they would reply: “What can we do? It is the same everywhere. In every restaurant and hotel the girls are looked upon as common prostitutes and are treated as such.”

The fellow worker says that while working in this restaurant she resented an insult hurled at her by the chef, and for it she received a severe beating, was dragged down into the basement and locked up in one of the rooms and made so ill by such treatment that it was necessary to call a physician. Later she was taken home in a closed automobile.

She was also employed a few months ago in the Morrison Hotel, where she saw conditions equally as bad, if not worse. Here, she says, the kitchen and pantry help were compelled to slave fourteen and sixteen hours a day. The cooks and waiters were organized, but the “common” help was not. She asked these cooks and waiters why they did not attempt to organize the kitchen and pantry help.

They replied that they had nothing whatever to do with the kitchen and pantry workers; that if these girls and men did not like their conditions, let them organize; that it was no concern of the cooks and waiters. This attitude is characteristic of craft unionism. “To hell with our less fortunate fellow workers—just so WE get what is coming to us!” Under such circumstances who is to be blamed when these workers stay right on the job after the cooks and waiters have gone out on strike?

Fellow Worker says that the food served to the workers in the big hotels is positively as poor as can be imagined; that the girls are constantly complaining of being ill and sick at the stomach from eating such unwholesome food.

The hours are never regular. Sometimes the workers were compelled to work during the hours of rush and are then sent to the basement to “rest” and to be “off” for a few hours, during which time, of course, they were not paid. And then they had to report again for the next rush. And so, while they actually worked for ten to twelve hours, they were kept on the job for fourteen and sixteen hours.

They were compelled to come some days at 12 o’clock, get off at 3, back at 6, and off again at 1. Other days they came early in the morning and worked all day. Can such outrageous conditions be imagined in this twentieth century and in “free” America?

During the weeks prior to the strike the workers were slaving on an average of ten, eleven and twelve hours per day, seven days a week, for feom $10 to $15 per week.

While Fellow Worker— was being kept in jail by the benevolent authorities for the crime of attempting to call the workers out of the downtown lunchrooms she met some sixty or seventy girls and women who had been arrested as “immoral” women. She found that, with hardly an exception, these girls and women were workers in hotels and restaurants. Asked why they came to take up such lives, they replied: ‘There seemed to be no other way out. We did not receive sufficient wages in return for our eleven and twelve hours work in the eating houses to pay our room rent, laundry and other personal expenses, to buy clothing, shoes, etc., or to take in a show once in a while, so we were compelled to find other means of supplementing our incomes.”

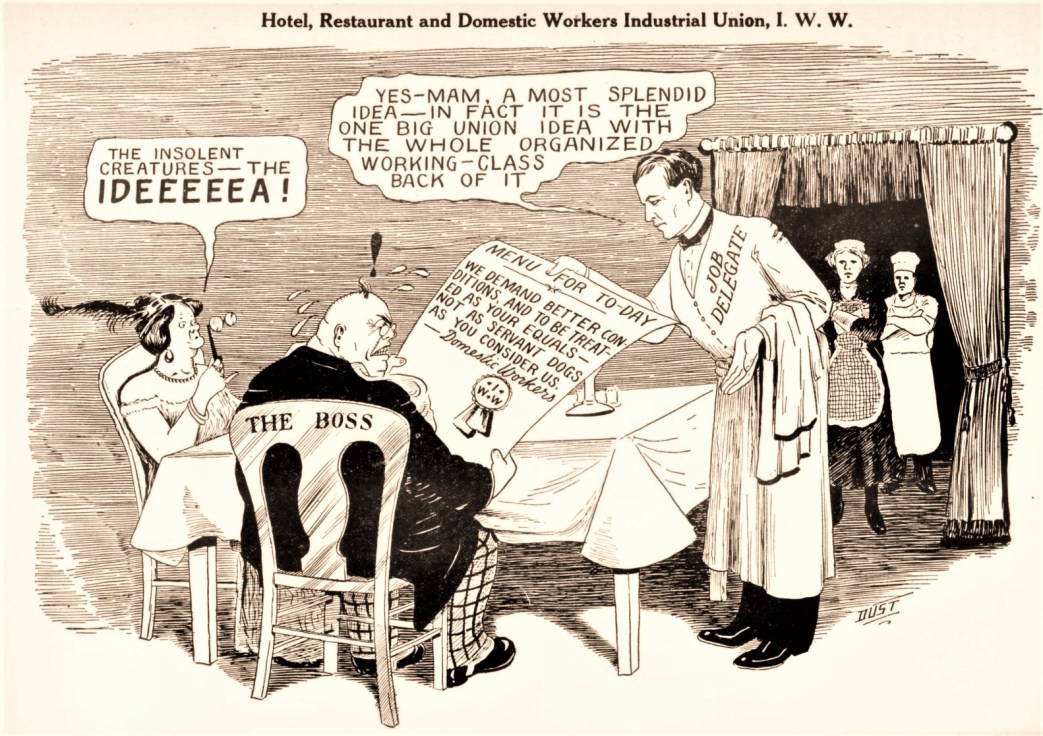

Fellow workers, is it any wonder these much-to-be pitied workers became interested in organizing a union? Is it any wonder they turned to the I.W.W. for help, after they were turned down by the American Federation of Labor?

And yet, when they held meetings, voted unanimously to enter the I.W.W., and decided to strike for eight hours, a minimum of $20 per week and a six day week, they were met at the lunch room doors by hired sluggers, gunmen and police.

One Big Union Monthly was a magazine published in Chicago by the General Executive Board of the Industrial Workers of the World from 1919 until 1938, with a break from February, 1921 until September, 1926 when Industrial Pioneer was produced. OBU was a large format, magazine publication with heavy use of images, cartoons and photos. OBU carried news, analysis, poetry, and art as well as I.W.W. local and national reports.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_one-big-union-monthly_1919-10_1_8/sim_one-big-union-monthly_1919-10_1_8.pdf