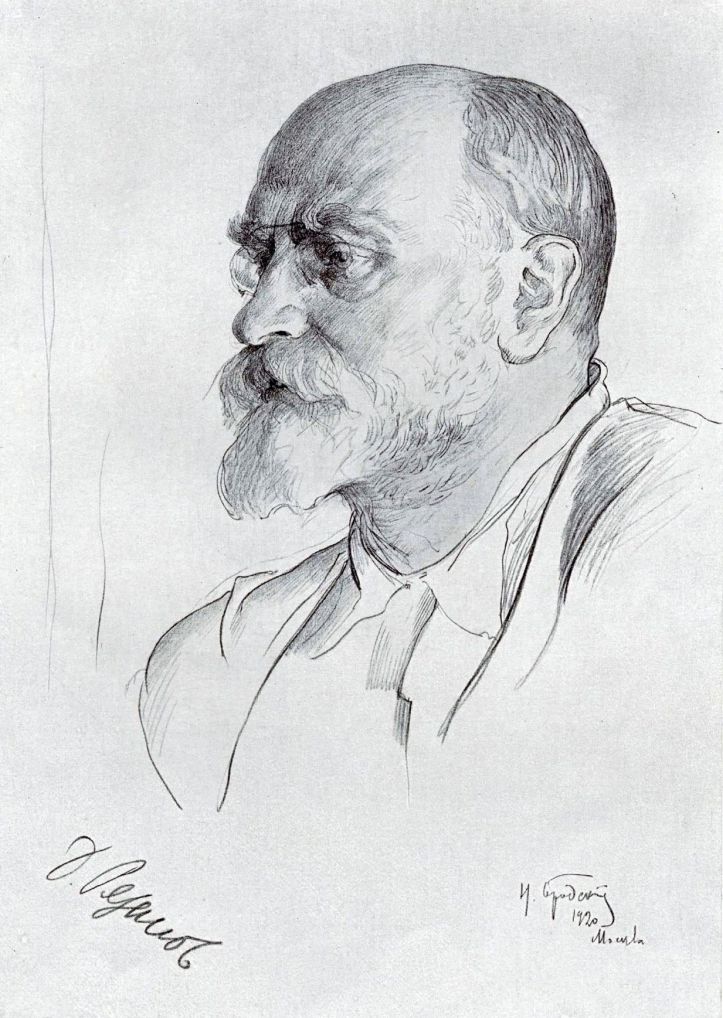

There is not a better introduction to the establishment of the First International than this essay written for the 60th anniversary of David Riazanov, director of the Marx-Engels Institute and foremost Marx scholar of his generation.

‘The Founding of the First International’ by David Riazanov from International press Correspondence. Vol. 4 No. 67. September 25, 1924.

After the defeat of the revolution in 1848, a defeat involving the suppression of all movements of the working class on the continent and in England, ten years passed before the labour movement began to rise again, and the International Labour Association emerged from the rising waves. During this decade of political reaction, and of hitherto unexampled economic prosperity, scarcely impeded by the Crimean war and participated in by the whole of the countries of Europe, Russia not excluded, a new generation grew up, and this generation did not awaken from its political indifference until the world-wide crisis of 1857-1858. The political revival beginning in 1859, and again raising many of the national and political questions which had been put before the revolution of 1848, but never answered, again filled the democratic movement everywhere with fresh life. And from 1858 onwards the abolition of slavery in the United States and in Russia became practical questions of the day.

The English Labour Movement in the Fifties and Sixties.

In England, where Chartism had lost its last organ in 1858, after Ernest Jones had failed in the attempt to impart to Chartism the character of a class movement, and it had ceased to exist as united political organisation, the labour movement split up entirely. Its old tendency of dissolving into separate sectional movements with different aims, and into various organisations all competing with one another for the attainment of the same object a tendency to which Chartism had also been liable now gained the upper hand again. There was not a trace to be found of a united labour movement with united leadership.

Political conditions most favoured the development of those forms of the labour movement which did not run directly counter to the ruling reaction, and thus enjoyed the patronage of bourgeois philanthropists. Headed by the honest pioneers of Rochdale, the co-operative societies gained firm ground in the fifties, and played a leading role among the forms of activity taken by the labour movement at that time.

The fifties were however not very favorable for the trade union movement. Except for a few exceptional cases, the trade unions kept going with the greatest difficulty. The tendency gaining the upper hand was that which regarded any political action as a disturbing element.

But the situation was changed at one blow after the crisis of 1857. “The era of strikes” – say the Webbs – “which began in 1857 with the decline of business, proved how deceitful these hopes had been.”

The most important strike of this period was however the strike in the London building trade.

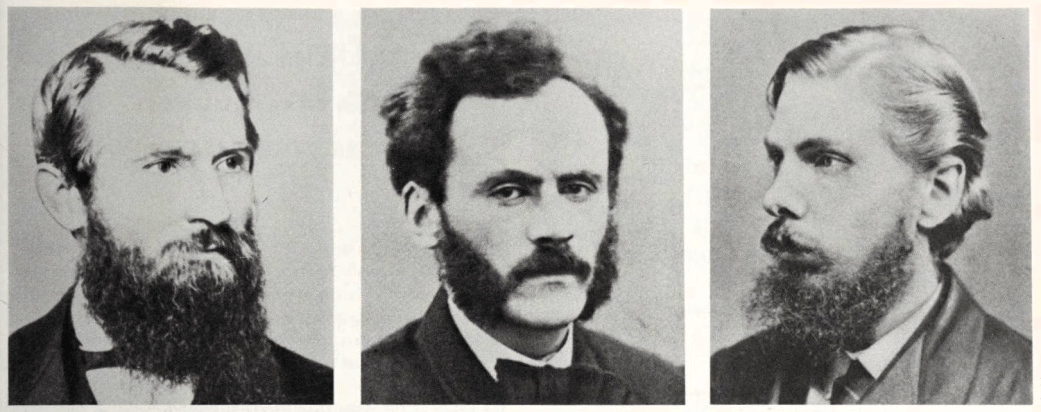

The whole of the English trade unions supported the building workers of London. For the period of half a year (from 21st July 1859 till 6th February 1860) this strike kept the English working class in a state of excitement. The workers’ representatives and members of the committee (formed of delegates from different trades) – especially G. Odger, the future chairman, and W.R. Cremer, secretary of the general council of the International Labour Association- explained the demands of the workers at the meetings. “If political economy is against us” cried Cremer at a meeting in Hyde Park: “then we shall fight against it.” The whole struggle was regarded as a fight between the political economy of the working class and the political economy of the capitalist class.

The first building workers’ strike ended with a compromise. The workers abandoned their main demands for the time being. Despite this, this strike formed a turning point in the history of the English labour movement. The struggle for the right of coalition induced even the most peacefully inclined trade unions to take part. The trades committees formed during these strikes for the purpose of organising the collection resulted in many places in the formation of Trades Councils, amongst others the London Trades Council (July 1860), which now undertook the task of defending the common interests of the workers in the struggle against the capitalists.

And when the next great building strike broke out in the spring of 1861, the building workers were backed up from the beginning by all the London trade unions. The newly formed London Trades Council exerted its utmost forces in support of the building workers’ demands. It was this Council which organised the whole action against the employment of soldiery as strikebreakers. The deputation sent to the government in accordance with the resolution passed by a delegates meeting of all London trade unions, convened by the Trades Council, consisted of the following: S. Coulson, W. Cremer, G. Howell, Henry Martin, John Hieasz, G. Odger – all members of the future General Council of the International.

The second strike brought the building workers not only the same security for their coalition rights which the first had brought, but at the same time shorter working hours. A standard working day of 9 1/2 hours was fixed.

But the strike movement of 1859 till 1861 not only brought about a closer feeling between the local trade unions, and an awakening of class solidarity among the English workers, but it had another important result. The employers, who always brought up foreign competition when resisting the trade unions, now threatened to import cheap foreign labour. This threat was no empty one, as the increasing competition of Germany in the tailoring and baking trades speedily showed. The struggle for equal working conditions had to be extended to the continent. Thus the international propaganda of the trade union organisation became a matter of vital importance for the English workers, and they became conscious of the need of establishing connections with continental workers, especially in France, Belgium, and Germany.

The many fugitives living in London offered excellent opportunity for entering into such communication. At this time, after a large number of the French workers had either emigrated to America or returned to France after the amnesties of 1856, the central resort of proletarian emigrés was the “Communist Workers’ Educational Union”, whose members were actually recruited mainly from the handicraft class (tailors, painters, watch- makers), and, like Eccarius and Lessner, both members of the old “Union of Communists”, were at the same time active members of the English trade unions.

There was speedy opportunity of entering into immediate communication with workers on the continent, through the intermediation of various refugees. The third World Exhibition was opened in London in May 1862, and was attended by labour delegations from various countries. The French delegations were the most numerous.

French Workmen in England.

The defeat of the revolution of 1848 was felt more severely by the French proletariat than by any other. The government which had seized power by a coup d’état now ruthlessly suppressed any independent movement in the working class. Various police measures and prohibitions were combined with endeavours on the part of the Empire to reconcile the workers with the new regime by means of improvements in the material situation of the working class, a kind of “imperial socialism”.

But the crisis of 1857-58 brought about a change in France, as in England. All delusions on “imperial socialism” were abruptly dispelled. Despite the anti-combination-law, the crisis was immediately followed by a strike movement in defence of the old wages. The excitement among the working population was very great. The Italian war, which had been undertaken in order to provide a safety valve for the discontent prevailing within the country itself, called forth much enthusiasm among the working population, but this changed to a storm of indignation as soon as the conditions of the peace of Villa Franca were made known. It now became evident that there was no turning back. But on the other hand it was equally evident that the further development of the Italian question would further increase the dissatisfaction of the clergy. A counter-weight could only be formed by the working class, and by the liberty-loving bourgeoisie and petty citizen class. Therefore the first steps were taken towards a “liberal empire”, and towards the rapprochement to England which was expressed in the trade agreement of 1860.

In the imperial family Prince Napoleon was the chief representative of the liberal and anti-clerical tendencies. His confidant was Armand Levy, who had been active in the revolution of 1848, and had been tutor to the children of Mickiewicz, the great Polish writer. He succeeded in gaining the collaboration of many representatives of various associations for his newspaper, which defended the cause of all suppressed nationalities, and devoted much space to the labour question. He was successful in forming a group among the Parisian workers, and this supplied him regularly with correspondence. In collaboration with these correspondents Levy published a series of pamphlets formulating the demands of the workers in the spirit of imperialist socialism.

It was with this group that the idea originated of forming an own labour delegation for the London World Exhibition. This same Levy acted as chief intermediary between the workers and Prince Napoleon, who was chairman of the imperial exhibition committee. It was this circumstance, the alleged semi-official character of the labour delegation, which was utilised later on various sides against the French members of the International.

In reality the matter was very different. Among the Parisian workers there was another group, mostly followers of Proudhon, willing to take part in the delegation under certain conditions only. This group was headed by Tolain. It was successful in having the election of the delegates carried out by the workers themselves.

But how little the meeting held on 5 August 1862, at which the French labour delegation was ceremoniously welcomed, can be regarded as starting point of the International Labour Association, is demonstrated by the fact that the leaders of the English trade unions had nothing whatever to do with the whole matter.

Those arranging the meeting emphasised from the beginning that the reception was not prepared by the English workers alone, but by the English employers as well. The meeting was arranged under the aegis of those same exploiters who, a few months before, had fought the English workers with all the means at their disposal. Thus no definite propositions were made for bringing about a permanent connection between French and English workers. The addresses held by French and English alike did not place the interests of the working class in the foreground, but those of industry, and the necessity of an understanding between workers and employers was emphasised as sole means of improving the unfavourable position of the working class. No word was uttered on the necessity of the working classes of different countries combining with one another in their struggle for emancipation. And yet the visit made by the French to the London world’s exhibition was indirectly of great significance, for it proved a very important stage on the road to an understanding between English and French workmen. The contact with English comrades, and the becoming personally acquainted with English conditions, have borne fruit.

One of the most important results was the separation of the workers following in the track of “imperial socialism” from those who, under the leadership of Tolain and his friends, wished to be free from any official control.

There is no doubt but that the French delegates entered into communication with English trade union leaders, perhaps through the intermediation of some of the French emigrés. The connections thus formed were then maintained by the members of the French labour delegation, who found headquarters in London and settled there permanently for instance E. Dupont, the future secretary of the International for France.

But these connections between English and French workers, made during the visit of the delegation, would have been speedily dissolved had not two events the cotton famine and the Polish insurrection called forth parallel movements on both sides of the Channel.

The cotton famine, a consequence of the civil war in North America, became exceedingly acute in the years 1862 and 1863. The situation of the workers in Lancashire was frightful. And the French textile workers suffered equally.

In London a workers’ committee was formed, headed by Odger and Cremer, and in Paris a similar committee was formed almost simultaneously, under the leadership of Tolain, Perrachon, Kin, and others, for the purpose of organising collections for the suffering workers.

The action taken in aid of the Polish insurgents was equally parallel. The English workmen, despite the want and misery caused them by the civil war in North America, held great mee- tings for carrying on an energetic campaign against the government, which was inclined to take the part of the slave-holders. They also held a number of meetings expressing their sympathy with the Polish insurrection, which began at the beginning of 1863, and exerted every endeavour to exercise such pressure on the government as would induce it to act in a friendly manner to- wards the Poles. A delegation elected by one of the meetings in St. James Hall (held on 28th April 1863, under the chairmanship of Professor Beesly) was received by Palmerston, but received an evasive reply. In order to put greater pressure on the government, it was decided to convene another meeting, participated in this time by the representatives of the French workers.

Tolain and his friends accepted the invitation of the English workers. The meeting was held in St. James’ Hall on 22. July 1863. Cremer spoke for the English workers, and subjected the whole of Palmerstons’ foreign policy to a severe criticism. Odger also spoke on behalf of the English workers, and demanded war against Russia. Tolain spoke on the same lines, eloquently describing the sufferings of the Poles, and emphasising the necessity of putting a stop to Russian barbarism.

Immediately after the meeting, the English and French workers held consultations, discussing the necessity of closer and more permanent connection.

And now it was the London Trades Council which grasped the initiative as fully authorised representative of the workers of London. On 23rd July the Council arranged a festive reception for the French workers. The secretary, Odger, welcomed the French workers, and expressed the hope that the day was not far distant when the workers of all countries would join together, when war and slavery would disappear, and their place be filled by liberty and universal welfare. A Polish delegation was also present. A German worker, a weaver, spoke of the advantageous effects of co-operation between the workers of different countries.

Preparations for an International Labour Association.

It was unanimously resolved to appoint a committee com-issioned to draw up an address to the French workers. But more than three months passed before the committee had completed this task, and the draft of the address was submitted to a new meeting. (10. November 1863.) The address was supported by Odger, Cremer, and Applegarth (who died recently), and was unanimously approved.

In the second half of November the address was translated into French by Professor Beesly, sent to the Paris workers, and eagerly read in all the suburbs of Paris.

This address of sympathy expresses the idea that solidarity among the nations is best furthered by the union of the workers of all countries. An international congress is proposed as intermediary.

“Let us convene a meeting of representatives from France, England, Italy, Poland, and all the countries possessing the will to mutual work for humanity. Let us hold our congresses, let us discuss the great questions upon which the peace of the peoples depends.

The fraternisation of the peoples is the first necessity for the cause of labour. For whenever we attempt to improve our social position by shorter working hours or increased wages, our employers threaten to bring over Frenchmen, Germans, or Belgians, who will do our work for lower wages. We are unfortunately obliged to admit that this has already been done, though not through any intention on the part of our brothers on the continent, out through lack of a regular and systematic connection among the working slaves of all countries. We hope that this connection will be actualised, for our principle of raising the wages of badly paid workers as far as possible to the level of the better paid workers is one which puts an end to the employers’ device of playing us off one against the other, and thus lowering our standard of living to suit their mercenary spirit.”

More than eight months passed before an address in reply to this was received in London from the French workers. This delay is to be explained by the fact that the Parisian workers were preparing for the second ballot elections held in March 1864. It was the first attempt at separation from the bourgeois opposition. In a manifesto (Manifest des soixante), drawn up by Tolain and signed by sixty workers, including Calélinat, the present treasurer of our French sister party, the necessity of independent political activity on the part of the working class is explained. The fundamental principles of the manifesto were Proudhon’s, but with the difference that the “sixty” declared themselves in favour of active participation in the elections, whilst Proudhon was opposed to this.

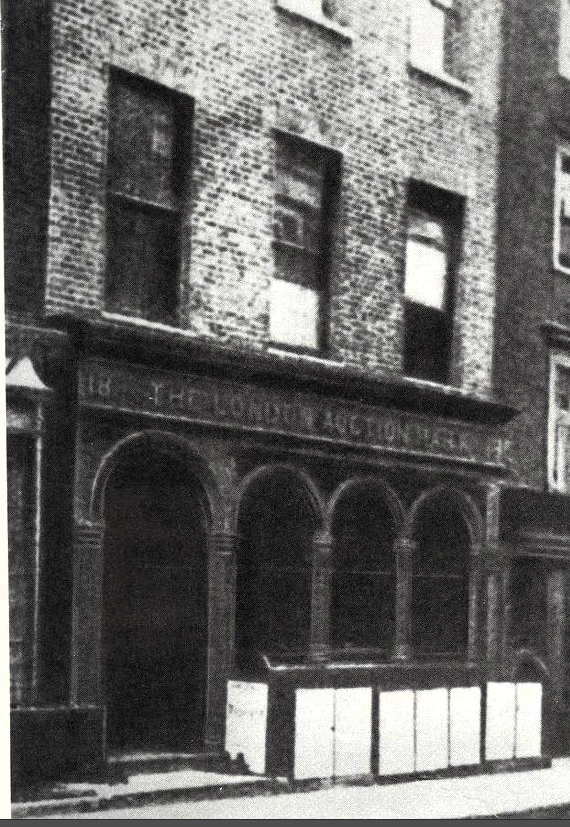

It was not until after these elections that negotiations with the English workers were renewed. The intermediaries were Henri Lefort, who is still alive, and his friends among the French refugees. Lefort had also lent his aid in the elections. It was decided that the address replying to the English workers should be carried to London by a delegation elected for the purpose. On the 17th September 1864 the English labour paper, the “Beehive” published the announcement that on Wednesday 23th September, 1864 a meeting would be held in St. Martin’s Hall, Longacre, at which a labour deputation from Paris would read their address in reply to the English workers, and submit a plan for the attainment of a better understanding among the peoples.

The Meeting at which the International was Founded.

At the meeting, which Marx described in a letter to Engels as “crowded to suffocation”, the chair was occupied by the same Prof. Beesly who had conducted the great Poland meeting the year before. His speech, in which he emphasised the necessity of an alliance between England and France, and expressed the hope that the result of the meeting would be co-operation and brotherly feeling between the workers of England and those of all other countries, was followed by the reading, by Odger, of the address sent by the English workers to the French, Tolain replied on behalf of the French delegation:

“Workers of all countries, if you want to be free, it is now our turn to hold congresses; the people, now awakened to the consciousness of their power, are rising against the tyranny of the political system, against the monopoly in social economy; for industry is developing its productive forces day by day, thanks to the advances of scientific discovery; the employment of machinery facilitates the division of labour and further enhances the power of industry; and the trading agreements realising the free trade idea open out new field for industry everywhere.

“Industrial progress, division of labour, free trade, these are the three new objects which must chain our attention, for they are going essentially to alter the economic conditions of society. Urged by the might of facts, and by the needs of the times, the capitalists have combined together in mighty financial and industrial companies, and if we do not take up measures in defence, the pressure of this preponderance will not be counteracted by any counterweight, and will speedily rule us despotically. We workers of all countries must unite to throw impassible barrier before this disastrous system, which will otherwise divide humanity into two different classes, into a mass of starved and brutalised beings on the one hand, and a clique of overfed snobs and mandarins on the other. Let us help one another by solidarity that our goal may be reached. This is what our French brothers have to propose to our English brothers.”

Le Lubez, who translated Tolain’s speech into English, then submitted to the meeting the plan of action proposed by the French workers: a central commission, formed of workers from all countries, was to be established in London, whilst sub- commissions were to be appointed in all the capital cities of Europe, and to correspond with the central commission in London. The central commission was to submit questions for discussion, which were then to be simultaneously discussed by all sub-commissions, and the result communicated to the central commission.

A congress was to be held in Belgium in the course of the following year, attended by representatives of all the working classes of the different countries. This congress would arrange the final form of the organisation. After an address of Lefort’s had been read, Wheeler proposed the following resolution:

“The meeting, having heard the reply sent by our French brothers to our address, once more welcomes the French delegation, and as their plan is calculated to further unity among the workers, the meeting accepts the draft just read as the basis for an International Association. At the same time it appoints a committee, authorised to increase its membership, commissioned to draw up the statutes and regulations of the proposed association.” The resolution was seconded by Eccarius on behalf of the Germans, by Major Wolff for the Italians, by Bosquet for the French, by Forbes for the Irish, and was passed with acclamation.

This is all we know about this historical meeting. The members of the provisional central council were commissioned to work out the statutes, but no definite lines were prescribed for this. Even the name of the newly founded association was not decided upon. The committee was left to pour basis principles into the new mould of an international association as best they could. The formulation of this declaration of principles was thus left to the varying opinions obtaining in the committee itself.

Marx and the International.

It is to the German communist Karl Marx that thanks are mainly due for the program drawn up and the statutes drafted for the International Association thus created by the English and French workers.

In the official report his name is first mentioned among the members of the elected committee, where it takes the last place. This circumstance alone proves that his name was known to the conveners of the meeting. He himself writes as follows on the subject:

“A certain Le Lubez was sent to me, asking if I would participate on behalf of the German workers, and especially if I would send a German speaker for the meeting, etc. I sent Eccarius, who managed splendidly, whilst I assisted him as dumb figure on the platform. I knew that on this occasion real “powers” both from London and Paris would be figuring, and thus decided to depart from my otherwise fixed rule of declining all such invitations.”

W.C. Cremer, a carpenter, had invited him to the meeting in a letter, which reads as follows:

Dear Sir,

The committee organising the meeting announced in the enclosed invitation begs respectfully for the honour of your presence. The production of this letter will gain you entrance to the room in which the committee meets at half past 7.

Yours truly,

W.R. Cremer.

Thus, though it is scarcely possible to designate Marx as the founder of the International Labour Association, still there is no doubt but he was its intellectual leader from the time of the first session of the provisional general council. With the help of Eccarius he opposed every attempt towards transforming the new association into a new variation of the former “International Association”, or to amalgamate it with another, as for instance the “Universal League”, on whose premises the provisional council held its first meetings.

At the second session (12th October 1864) a resolution was passed, proposed by Eccarius and Whitlok, giving the new society the name of “International Labour Association”.

In the sub-commission, commissioned to draft the statutes, Marx succeeded in securing victory for the fundamental ideas of scientific socialism. He was obliged to grant some concessions in the debate with French and Italian revolutionists, but on the whole the “Inaugural Address” proposed by him, as also his declaration of principles, were approved as best expression of the demands of the working class by almost all the workers in the General Council. At the fourth session of the provisional General Council, on 1st November 1864, Marx read his work, which, with a few alterations in the style, was unanimously accepted.

From this day onwards the First International had its program, and on this day the young organisation could begin its work of propaganda.

The “Inaugural Address” of the International Labour Association closed with that same appeal of: “workers of the world, unite”, which had formed the closing words of the Inaugural Address of the first International Workers’ Union, the Communist Manifesto, the first to proclaim united action among the workers of all countries as one of the most important conditions for the emancipation of the proletariat.

But that which had been the appeal of a tiny minority, of a small group whose internationality lay mostly in its programme, had now become transformed into an appeal sent forth by a labour organisation international in its membership and its programme alike. Thousands and thousands of workers gathered together for self-emancipation in the sections and groups of the First International. The alliance of the workers of all countries which it founded now celebrates its renaissance in the new International with its millions of proletarians.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1924/v04n67-sep-25-1924-Inprecor-loc.pdf