‘The Burlesque Strike’ by Del from New Theatre. Vol. 2 No. 10. October, 1935.

On Thursday, September 5th, the burlesque emporiums of New York opened as usual. The customary crowd paid their admissions, brass-lunged vendors hawked their wares up and down the aisles of the theatres, lights were dimmed. Tired bandsmen filed into their accustomed places and except for the steady patter of rain outside, nothing seemed amiss.

The predominantly male clientele settled its wet feet on the balcony rails, placed its dripping hats under chairs, leaned back and patiently awaited an end to the preliminary cacophony of pleasant and familiar sounds the swish of candy paper, the crackle of newspapers and the unabashed tuning of saxes and brass.

On this particular afternoon, the curtain seemed ominously still. For instead of rising to disclose animated rows of effulgent blondes and flashing legs, the houselights went on and a prosaic looking manager came on to convey a message that brought from the audience cat-calls, hisses and boos.

The show would not go on, he said, because the cast had gone on strike. The money, he added ruefully, would be refunded at the box office!

Considerably disgruntled, the audience finally left the theatre. No escape! Inside the theatre or out! The ubiquitous struggle for better living and working conditions had even reached across the footlights to these dames, who were supposed to make you forget your troubles!

Consciously or not, the audience had witnessed labor history in the making. It was the first strike led by the Burlesque Artists Association.

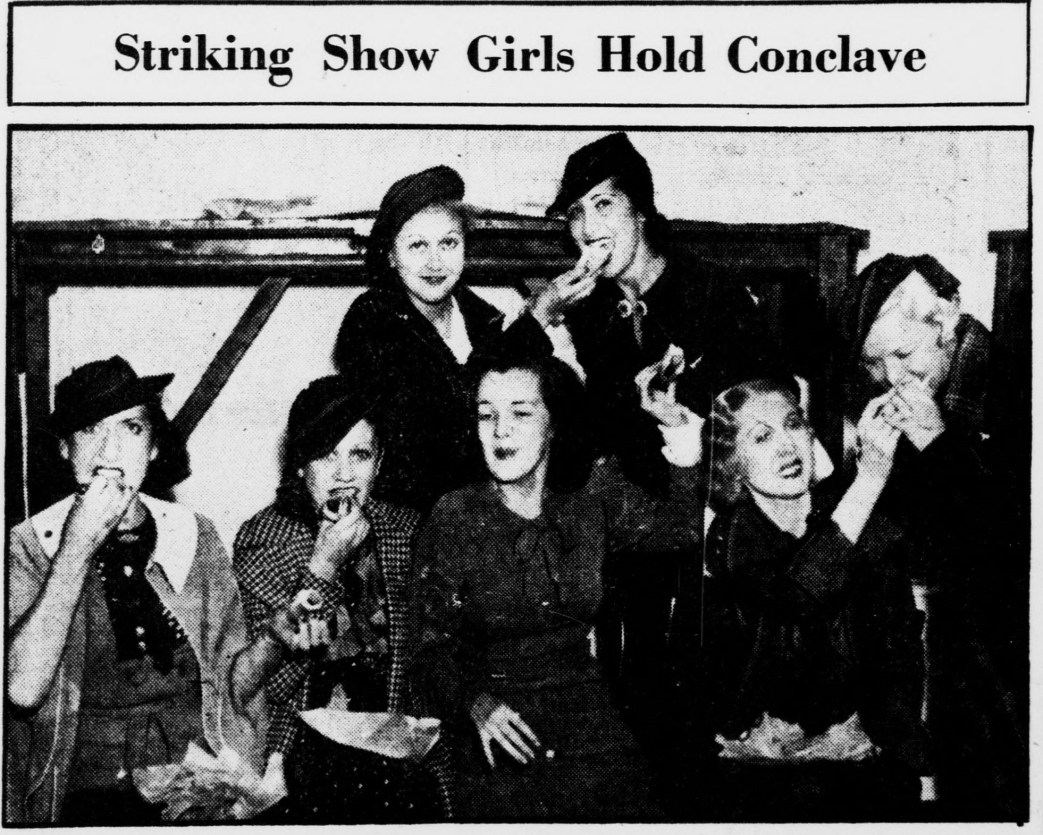

A visit to strike headquarters in Union Church on 48th Street just off Broadway, provided some strange sights indeed. We had to push our way through dense crowds, some listlessly watching the antics of a corner evangelist, others attracted to the brilliantly lighted Strand Theatre which was loudly paging Mr. Hearst’s “Glory.”

At the strike meeting, some of the performers seemed bewildered by their first experience. We posed a question to a vivid brunette with an amazing hat perched at an amazing angle. “You’ve got me buddy,” she answered, “I’ve been here eight hours and I still don’t know what the hell it’s all about!” However, a strikingly beautiful blonde parade girl, in the manner of a veteran trade unionist, did know what it was all about.

“We’ve been getting $21.50 a week for stock and $23.50 on the road for an eighty hour week. No day off. This isn’t show business. It’s slavery.”

A chorus girl sitting with a male performer, who proudly announced himself an “organizer” told us, “This thing started with almost nothing and it’s getting bigger all the time. We didn’t have to be convinced that we needed better conditions. We needed leadership and once we got it, we felt that nothing could stop us.”

With such splendid spirit it was a foregone conclusion that the strike would be won. Three days later, the strikers returned to their theatres after registering a solid victory. $22.50 for stock, $25.00 on the road and a day off every fourteen days were the demands that were won. Also a minimum of $40.00 a week for principals. Such demands as two weeks’ salary guaran- tee against possible closing through revocations of licenses and police raids are to be arbitrated with an impartial board.

The Minskys, virtual dictators of the industry, indignantly denied that the strikers had won any victory, because as the youngest and loudest Mr. Minsky expressed it, “We were going to give them more money anyway.”

In his closing speech to the strikers, Tom Phillips their leader, made a remark that should put the strikers on their guard. “Go back to your theatres,” said Mr. Phillips, “not as though you have won a victory, but as if nothing had happened. If the stage hands or musicians ask you how you feel about the strike, just mind your own business and don’t discuss it with them.” Such an attitude cannot but weaken the burlesque performers in their struggle against the employers for better conditions. For, as labor experience has shown, victory lies in the ability to unite with one’s fellow workers so that a strike of one group may greatly multiply its strength with the support of allied groups.

But these fledgling unionists must be congratulated on the splendid manner in which they conducted their first strike. Not only did they prove that burlesque people are capable of conducting a serious struggle to better their conditions, but they proved that there exist whole strata of people in the stage professions for whom there is a crying need for organization.

Producers in every phase of theatrical activity have long nursed the tradition which stated that the “show must go on!” Well, it was a swell slogan for producers for it meant that nothing may interfere with the steady stream of profits into their pockets, but what about the performers? Burlesque has given the classic answer, “The show WON’T go on unless we get decent working conditions!”

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v2n10-oct-1935-New-Theatre.pdf