Leonard Abbott reviews the history of one of the most influential of all English-language Socialist publications, William Morris’ ‘Commonweal.’

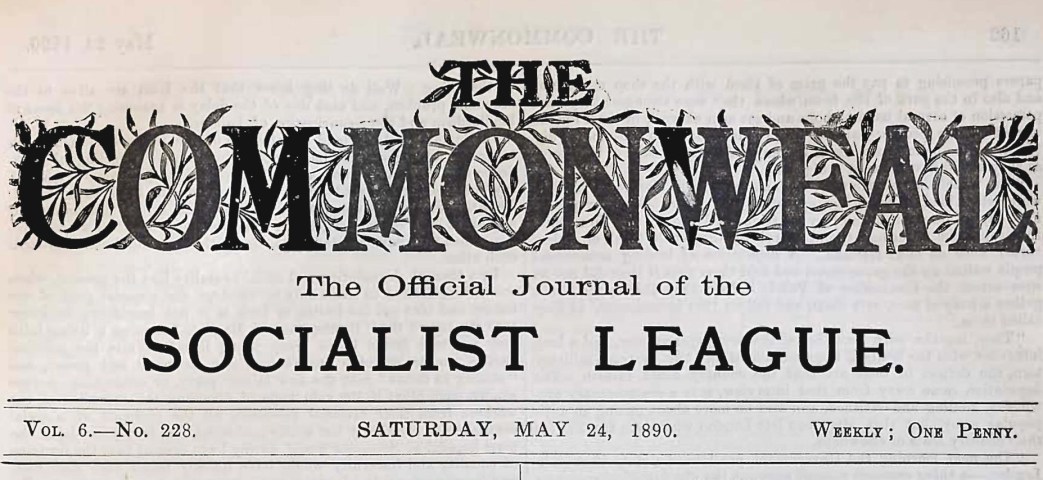

‘William Morris’s “Commonweal” by Leonard D. Abbott from The Comrade. Vol. 3 No. 4. January, 1904.

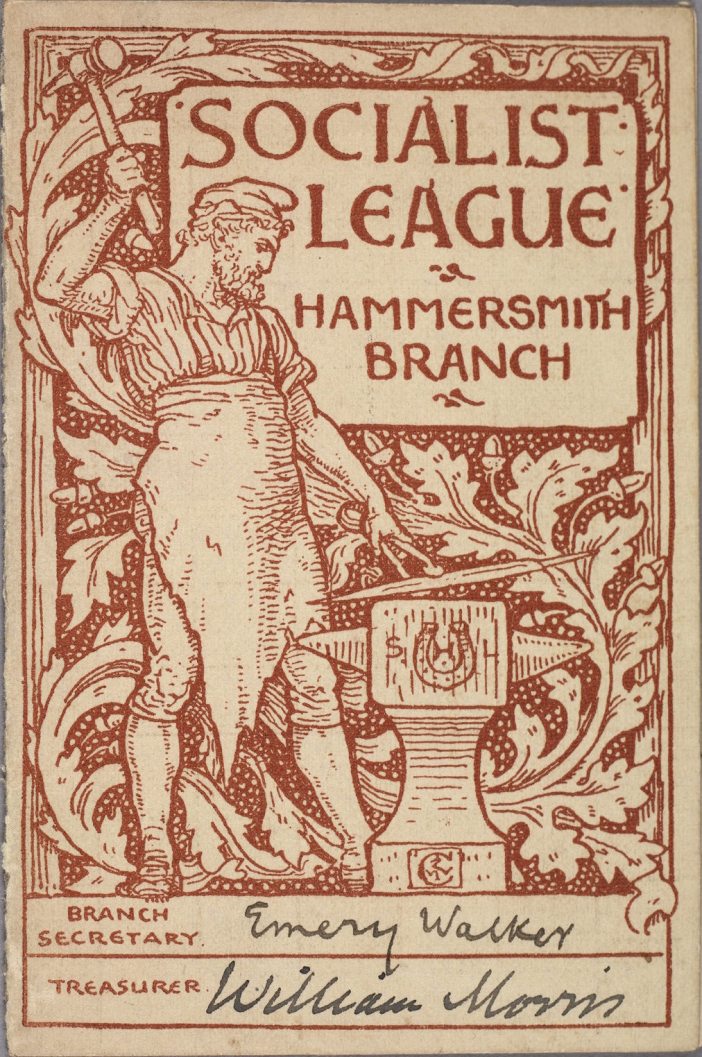

N the evening of December 30, 1884, William Morris, Edward Aveling, Eleanor Marx, Ernest Belfort Bax, and eight others, met together in a little room in Farringdon street, London. The result of that conference was twofold. First, a new organization, the “Socialist League,” came into existence. Second, a new paper, the “Commonweal,” was started. Neither the organization nor the paper lasted half a dozen years. They were what the world would call “failures.” But, if one may be per- mitted the paradox, they were successful failures. That is to say, they did their work and exerted an influence so subtle and far-reaching that it would be impossible to calculate its extent.

The first number of the “Commonweal” appeared in February, 1885, and for a year the paper was issued as a monthly. During this early period Morris was joint editor with Dr. Aveling, whose cold articles on “Scientific Socialism,” illustrated by algebraic formulae, appeared side by side with Morris’s passionate poems. It is not surprising that the two fell out after a year together; and Aveling gave place to H. Halliday Sparling. Sparling was an Irish- man with a good deal of literary ability. He edited for London publishers the sagas of Iceland and songs of Irish minstrelsy. In 1890 he married Morris’s second daughter, May, but the marriage was an unhappy one and culminated in a divorce. Sparling’s contributions to the “Commonweal” appeared mostly during 1886 and 1887, and when he withdrew his active support, and Frank Kitz and David Nicoll came to the fore, the paper began to show signs of marked degeneration. Both the last named were workingmen with Anarchistic tendencies, and their articles were characterized by language that frequently exceeded the bounds of good taste. Morris became disgusted, and withdrew both his literary and financial support. Nicoll thereupon assumed charge of the paper, with disastrous consequences. His articles grew more and more violent in tone, and he was finally arrested on a charge of “inciting to murder.” So the “Commonweal” came to an ignominious end!

The palmy days of the “Commonweal” (though it was never financially self-supporting) were during the first two or three years of its existence, when Morris was deeply interested in its welfare, and wrote generously for its pages. His first contribution to the paper was the now famous “March of the Workers.” In the second issue appeared “The Message of the March Wind,” an exquisite love poem, which he was led to expand into an unfinished series, bearing the general title “The Pilgrims of Hope.” This serial poem describes the awakening of two lovers to a sense of the social injustice around them, and their strenuous efforts to “set the crooked straight.” It contains without doubt some of the finest work of Morris’s lifetime, and its vivid scenes, no longer taken from classical lore, nor from the great epics of the North, but from the grim, sordid present. mark an important epoch in his poetry. Here is an extract from the first installment, telling of a meeting of the “Communist folk.” It is of special interest, for Morris, in describing the lecturer, is obviously thinking of himself.

“Dull and dirty the room. Just over the chairman’s chair

Was a bust, a Quaker’s face, with nose cocked up in the air.

There were common prints on the wall of the heads of the party fray,

And Mazzini, dark and lean, amidst them gone astray.

Some thirty men we were of the kind that I knew full well,

Listless, rubbed down to the type of our easy-going hell.

My heart sank down as I entered, and wearily there I sat,

While the chairman strove to end his maunder of this and that.

And partly shy he seemed, and partly, indeed, ashamed,

Of the grizzled man beside him as his name to us he named;

He rose, thickset and short, and dressed in shabby blue,

And even as he began it seemed as though I knew

The thing he was going to say, though I never heard it before.

He spoke, were it well, were it ill, as though a message he bore,

A word that he could not refrain from many a million of men.

Nor aught seemed the sordid room and the few that were listening then,

Save the hall of the laboring earth and the world which was to be.

Bitter to many the message, but sweet indeed unto me.

Of man without a master, and earth without a strife.

And every soul rejoicing in the sweet and bitter of life;

Of peace and good-will he told, and I knew that in faith he spake,

But his words were my very thoughts, and I saw the battle awake,

And I followed from end to end; and triumph grew in my heart,

As he called on each that heard him to arise and play his part

In the tale of the new-told gospel, lest as slaves they should live and die.”

In the sixth number of the “Commonweal” appeared a prologue entitled “Socialists at Play,” spoken by Morris at an entertainment given by the Socialist League at South Place Institute, London, on June 11th, 1885. It begins:

“Friends, we have met, amidst our busy life,

To rest an hour from turmoil and from strife;

To cast our care aside while song and verse

Touches our hearts and lulls the ancient curse.”

The poem is too long to quote in its entirety. The following lines give some idea of its quality:

“So be we gay; but yet amidst our mirth,

Remember how the sorrow of the earth

Has called upon us till we hear and know,

And, save as dastards, never back may go!

Why, then, should we forget?

Let the cause cling About the book we read, the song we sing;

Cleave to our cup and hover o’er our plate,

And by our bed at morn and even wait.

Let the sun shine upon it; let the night

Weave happy tales of our fulfilled delight!

The child we cherish and the love we love,

Let these our hearts to deeper daring move;

Let deedful life be sweet and death no dread,

For us, the last men risen from the dead!”

William Morris’s prose contributions to the “Commonweal” were in many ways quite as notable as his poems. “A Dream of John Ball” was first published as a serial in the third volume of the “Commonweal.” How many of us, since then, have fallen under its spell and echoed its words! “News from Nowhere,” which has so recently appeared in the pages of the “Comrade,” with Jentzsch’s sympathetic illustrations, first saw the light in the sixth volume of the “Commonweal,” and has been reprinted in edition after edition.

Of smaller articles for the “Commonweal,” on all kinds of subjects, Morris wrote scores; and in almost every number there were editorials, “Notes on Passing Events,” “Political Notes,” etc., signed either with initials or full name. Many of Morris’s lectures-“How We Live, and How We Might Live,” “Feudal England,” “Monopoly,” “Useful Work Versus Useless Toil”-were printed in the “Common- weal.” “Under an Elm Tree” is a country soliloquy, in which Morris asks why men cannot be “as wise as the star- lings in their equality, and so perhaps as happy”; “The Worker’s Share of Art,” “Attractive Labor,” “Unattractive Labor,” elaborate Morris’s well-known views in regard to the pleasure of the common task. “The Revolt of Ghent” is a medieval fragment culled from Froissart’s Chronicles.

Morris must have found it very difficult to obtain articles even remotely approaching the standard he desired. At times second-rate matter went into the paper. A great deal of space was occupied by American correspondence of a dull and uninteresting kind. There were, however, a few writers of real ability who could be counted on for regular and competent work. Foremost among these was Bax, who collaborated with Morris in the second volume in the authorship of “Socialism from the Root Up,” since published in book form. Whatever one may think of Bax’s temperament and point of view, it is idle to deny the force and originality of his work. A large number of his essays, preserved in book form, first appeared in the “Commonweal.”

Other distinguished writers for the paper included Wilhelm Liebknecht, Frederick Engels, Paul Lafargue and Sergius Stepniak. Two of the most cultured contributors were Henry S. Salt and J.L. Joynes, Eton masters both. Joynes translated the poems of Freiligrath, besides contributing original verses and articles. The “Commonweal” has some interesting American associations. Laurence Gronlund, who visited Morris in 1885, wrote for it. So also did Percival Chubb and W. Sharman. The former is now one of the principals in the Ethical Culture Schools in New York. The latter’s widow lives in Yonkers.

A few artists were in active sympathy with the “Commonweal.” Walter Crane designed two beautiful head- pieces for the journal. He also contributed three cartoons- “Vive La Commune!”, “Mrs. Grundy Frightened at Her Own Shadow,” and “Labor’s May Day.” The only example of Morris’s art is to be found in the unpretentious willow pattern used as a background for the title of the paper.

In the “Commonweal” for November 15th, 1890, appeared a long article by William Morris, entitled “Where Are We Now?” A pathetic interest attaches to it, for it was Morris’s last contribution in the paper and reveals his mood with remarkable frankness.

“It is now some seven years,” he said, “since Socialism came to life again in this country. To some the time will seem long, so many hopes and disappointments as have been crowded into them.” The task they had set out to accomplish, he continued, was one of appalling magnitude, and he felt compelled to confess that the forces on the side of Socialism had been miserably inadequate. “Those who set out to make the revolution were a few workingmen, less successful even in the wretched life of labor than their fellows; a sprinkling of the intellectual proletariat, whose keen pushing of Socialism must have seemed pretty certain to extinguish their limited chances of prosperity; one or two outsiders in the game political; a few refugees from the bureaucratic tyranny of foreign governments; and here and there an unpractical, half-cracked artist or author.” Speaking of the inside of the Socialist movement, Morris could not conceal the fact that there had been “quarrels more than enough,” as well as “self-seeking, vainglory, sloth and rashness”; but he added that there had been “courage and devotion also.” “When I first joined the movement,” he went on to say, “I hoped that some workingman leader, or rather leaders, would turn up, who would push aside all middle class help, and become great historical figures. I might still hope for that, if it seemed likely to happen, for indeed I long for it enough; but, to speak plainly, it does not so seem at present.”

And so, with the waning of Morris’s enthusiasm, the “Commonweal” died and the record was scattered. There are very few files of the “Commonweal” in existence, and its scarce numbers are eagerly sought. In certain respects it was a crude effort. In many ways it must have utterly disappointed Morris himself. Yet the Socialist movement would be appreciably poorer without this paper. And, whatever its shortcomings, it was the most ideal venture, it furnished the most romantic episode, in latter-day journalism.

The Comrade began in 1901 with the launch of the Socialist Party, and was published monthly until 1905 in New York City and edited by John Spargo, Otto Wegener, and Algernon Lee amongst others. Along with Socialist politics, it featured radical art and literature. The Comrade was known for publishing Utopian Socialist literature and included a serialization of ‘News from Nowhere’ by William Morris along work from with Heinrich Heine, Thomas Nast, Ella Wheeler Wilcox, Edward Markham, Jack London, Maxim Gorky, Clarence Darrow, Upton Sinclair, Eugene Debs, and Mother Jones. It would be absorbed into the International Socialist Review in 1905.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/comrade/v03n04-jan-1904-The-Comrade.pdf