Ella Reeve Bloor shares her personal memories of Annie Clemence, one of the heroic leaders of the 1913-1914 Michigan Copper Strike which included the Italian Hall Disaster resulting in the death of 73 people including 59 children at Christmas Eve party in 1913.

‘Anna Clemence: The Story of a Militant Working Class Woman’ by Ella Reeve Bloor from Working Woman. Vol. 2 No. 7. July, 1931.

She was born of Slav parents in Michigan. Her father slaved in the Calumet mines for years, and when Annie was about nineteen years old, the Western Federation of Miners began its heroic battle to organize the copper mines.

In 1913-14, although the Calumet Hecla Copper Company, owners of the mines, received at that time, four hundred per cent dividends, and the superintendent received a salary of $125,000 plus his dividends, the miners received a very low wage. They lived in miserable shacks, and worked in deep, dangerous mines, some even running out under the Portage Lake, hundreds of feet under the ground. These miners used water drills, some of them weighing 175 pounds, holding them high over their heads. The walls of their “Claim” became slippery, and many of them fell to their death.

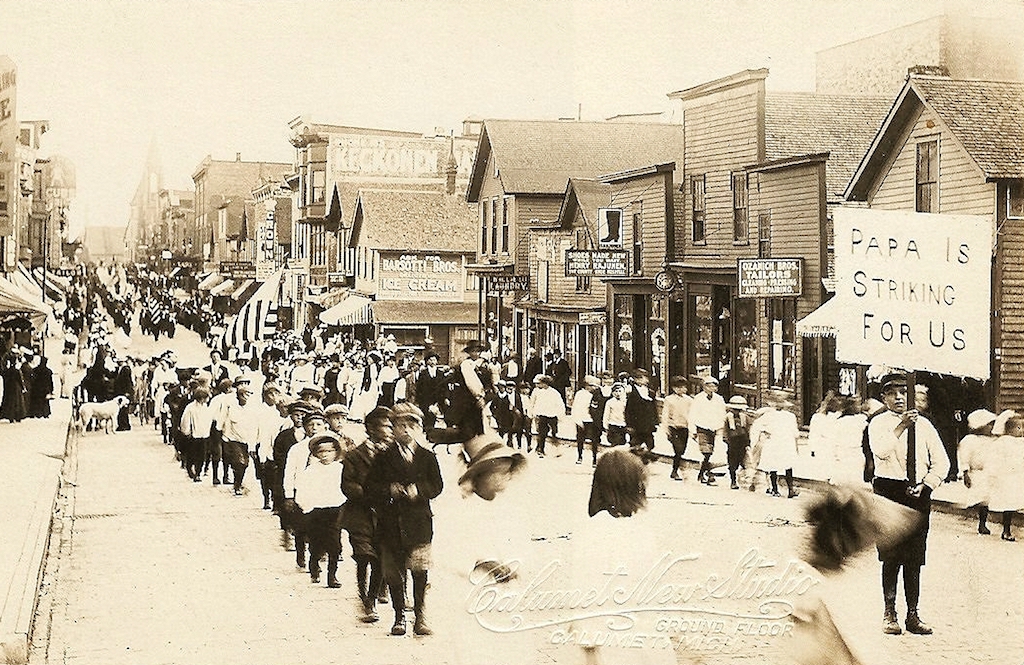

Their demands, as an organized part of the Western Federation were that two men should work on every drill and for the “right to organize.” These demands were torn to shreds when presented in writing to the superintendent. Then ensued one of the most tremendous strikes in our class history.

At this time I was a union organizer in Schenectady, N Y. We had also had a victorious strike against the. General Electric Company, of nearly 15,000 workers, machinists, iron molders, electrical workers, including 2,000 women. On account of our militancy we won the strike in about ten days.

The various unions connected with this strike appreciated my work so much that they gave me $150 and told me to go up to Michigan and help the women and children in the copper miners’ war. It was about Christmas time and it was bitter cold.

The day I arrived the Women’s Auxiliary of the Western Federation of Miners, numbering over 400 members, were holding a meeting in the large miners’ hall at Calumet. Annie Clemence, the president, came to the door in answer to my knocks and looked me over very critically. “Are you a union woman,” she asked. “Show me your card.” I showed her my union card and then I said, “Here’s my Red card, too.”

Her face beamed, as she said, “Come right in, I’ve got a Red one, too.” Here were gathered 400 miners’ wives and daughters from all the nearby camps. Their husbands and fathers had been on a strike for five months, but they were full of hope and courage. Annie not only led these Federation women, but she also led the picket lines from camp to camp to encourage the men.

One day while the soldiers were also marching from camp to camp to intimidate the strikers, she had led her group miles from Calumet to a remote camp. On the highway they met another group from Keweenaw mine. Annie was carrying, as she always did, an enormous American flag. The leader of the other group carried a smaller American flag.

Suddenly the soldiers swept down upon them and cut the smaller flag into ribbons. In reporting the incident at union headquarters, Annie said:

“When I saw that man’s flag cut to pieces, it made me mad, so,” she said, “I held my flag out in front of me and told them to go ahead and shoot me through the flag. Then the workers all over the U.S. would know what they did to their women and children in the copper country, and what they did to their flag.” “But,” she added, “they did not have the nerve.”

On Christmas Day about four o’clock, the children of the strikers gathered in the large Italian hall upstairs. They had just received their presents and were singing, when a door opened on the side of the hall, and a man with a Citizens’ Alliance button on his cap (the Alliance was a strike- breakers’ organization) opened the door and yelled “Fire!” There was no smoke, not a semblance of fire, but the children and some of the parents became panic stricken and rushed downstairs. The women, led by Annie, tried to quiet them, and no one realized how many had rushed down. At the foot of the stairs, a box entry had two doors which opened outward, Here the children were caught in a terrible trap.

The deputies and strike breakers gathered outside the door, held the door shut and, inside of four minutes, seventy-three of our children and a miner who had a child in his arms were suffocated to death. I saw the marks of the children’s nails in the plaster six feet from the floor where they had vainly clutched for a breathing place. Then the fiends who were the cause of this tragedy carried the dead children upstairs, and laid them in a row in front of the platform, Annie was screaming, “Are there any more dead?”

One deputy said, “What are you crying about?” Are any of these your children?”

She cried: “They are all mine.” “They are all my brothers and sisters,” and then she rushed at some priests, who were praying over the dead, crying, “You scab priests, don’t you dare to touch those children of our strikers.” The deputies then locked her up in the court house where they took the bodies of the children for the night.

The next day there was mourning in every home. The Citizens’ Alliance began to fear that they had gone too far, and sent their women to tell the mothers of the dead children that they would give them money to bury them. In one house a mother had lost three of her children. Here, when the strike-breakers’ women came and offered her money, she looked at them in a dazed way and cried, “You want to buy my children, you want to pay for them. I love my children as I love my soul, but I would rather put them in the ground naked than to touch a penny of your blood money.”

And so it was in every miner’s home. Not one penny was taken from the murderers.

Although all this terrible suffering was kept from the press, the workers’ press was putting it out to the world, with photographs of Annie Clemence carrying her American flag draped with Red and black, and one miner, carrying a Red Flag (their only hope).

The miners carried each little white coffin on their shoulders, marching through the snow to the graveyard.

I took Annie with me to all the larger cities of the Middle West to put our case before the labor men of the country and to raise money for the strikers, and their families. She made a great hit with the workers everywhere, with her dramatic stories of the strike, her sense of humor, and her beautiful loyalty to her class.

The Working Woman, ‘A Paper for Working Women, Farm Women, and Working-Class Housewives,’ was first published monthly by the Communist Party USA Central Committee Women’s Department from 1929 to 1935, continuing until 1937. It was the first official English-language paper of a Socialist or Communist Party specifically for women (there had been many independent such papers). At first a newspaper and very much an exponent of ‘Third Period’ politics, it played particular attention to Black women, long invisible in the left press. In addition, the magazine covered home-life, women’s health and women’s history, trade union and unemployment struggles, Party activities, as well poems and short stories. The newspaper became a magazine in 1933, and in late 1935 it was folded into The Woman Today which sought to compete with bourgeois women’s magazines in the Popular Front era. The Woman today published until 1937. During its run editors included Isobel Walker Soule, Elinor Curtis, and Margaret Cowl among others.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/wt/v2n07-jul-1931-WW-R7414.pdf