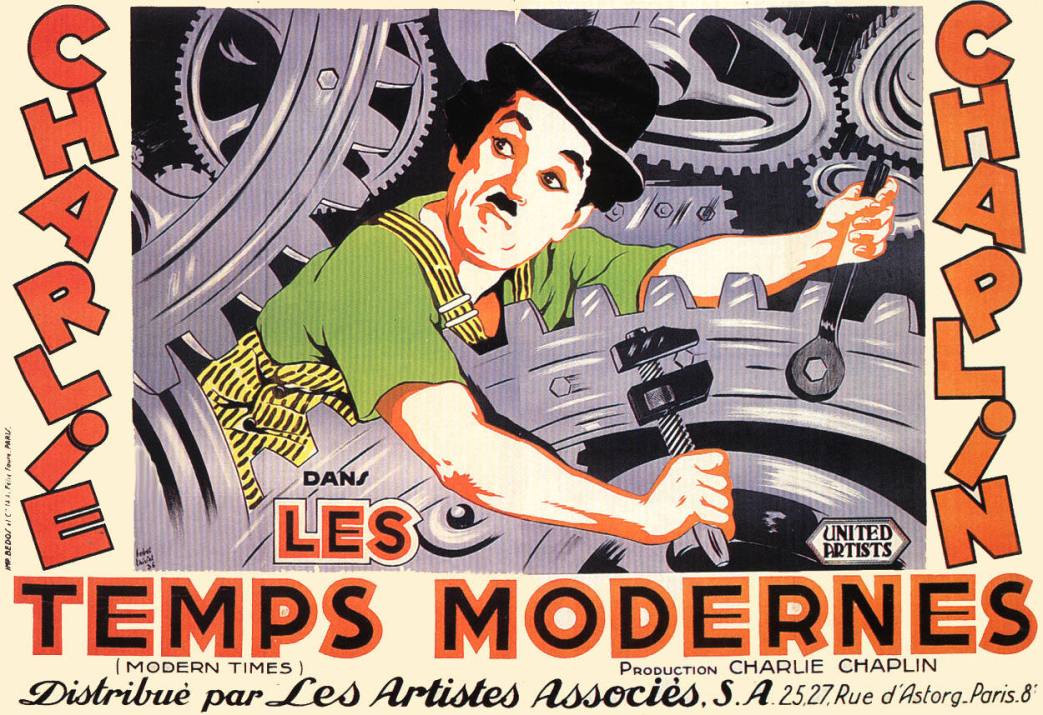

‘Chaplin in “Modern Times”’ by Robert Forsythe from The New Masses. Vol. 18 No. 8. February 18, 1936.

IF you have had fears, prepare to shed them; Charlie Chaplin is on the side of the angels. After years of rumors, charges and counter-charges, reports of censorship and hints of disaster, his new film, Modern Times, had its world premiere (gala) last week at the Rivoli Theatre, with the riot squad outside quelling the curious. mob and with the usual fabulous first-night Broadway audience gazing with some doubt at a figure which didn’t seem to be quite the old Charlie. For the first time an American film was daring to challenge the superiority of an industrial civilization based upon the creed of men who sit at flat-topped desks and press buttons demanding more speed from tortured employes. There were cops beating demonstrators and shooting down the unemployed (specifically the father of the waif who is later picked up by Chaplin), there is a belt line which operates at such a pace that men go insane, there is a heart- breaking scene of the helpless couple trying to squeeze out happiness in a little home of their own (a shack in a Hooverville colony). It is the story of a pathetic little man trying bravely to hold up his end in this mad world.

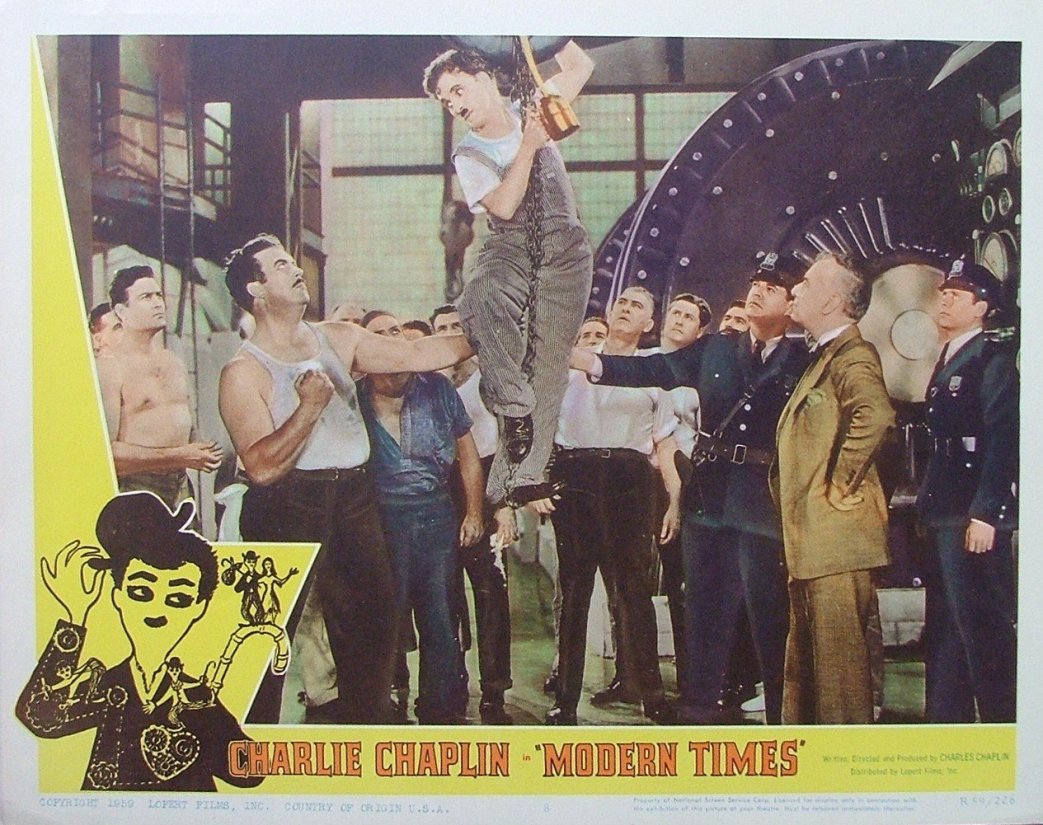

Chaplin’s methods are too kindly for great satire but by the very implication of the facts with which he deals, he has created a biting commentary upon our civilization. He has made high humor out of material which is fundamentally tragic. If it were used for bad purposes, if it were made to cover up the hideousness of life and to excuse it, it would be the usual Hollywood product. But the hilarity is never an opiate. When the little man picks up a red flag which has dropped from the rear of a truck and finds himself at the head of a workers’ demonstration, it is an uproarious moment, but it is followed by the truth- the cops doing their daily dozen on the heads of the marchers. In the entire film, there is only one moment where he seems to slip. After he meets the girl and gets out of jail for the third time, he hears that the factory is starting up again. What he wants most in the world is a home, where he and his girl can settle down and be happy. It is the same factory where he has previously gone berserk on the assembly line. From the radical point of view, the classic ending would have been Chaplin once. again on the belt line, eager to do his best and finding anew that what a man had to look forward to in that hell-hole was servitude and final collapse. Instead of this there. is a very funny scene where Charlie and Chester Conklin get mixed up in the machinery in attempting to get it ready for production. Just when they have it ready, a man comes along and orders them out on strike. At this point I was worried. “Uh- huh,” I said to myself. “Here it comes. The usual stuff about the irresponsible workers, the bums who won’t work when they have a chance.” But what follows is a scene of the strikers being beaten up by the police and Charlie back again at his life of struggle. Except for that one sequence the film is strictly honest and right. It is never for a moment twisted about to make a point which will negate everything that has gone before.

If I make it seem ponderous and social rather than hilarious, it is because I came away stunned at the thought that such a film had been made and was being distributed. It’s what we have dreamt about and never really expected to see. What luck that the only man in the world able to do it should be doing it! Chaplin has done the entire thing himself, from the financing to the final artistic product. He wrote it, acted in it, directed it, cut it, wrote the music for it and is seeing that it is sold to the distributors who have been frantic to get it. It is not a social document, it is not a revolutionary tract, it is one of the funniest of all Chaplin films, but it is certainly no comfort to the enemy. If they like it, it will be because they are content to overlook the significance of it for the sake of the humor.

And humorous it is. Chaplin has never had a more belly-shaking scene than the one where he is being fed by the automatic machine, with the corn-on-the-cob attachment going daft. The Hooverville hut is a miracle of ruin. When he opens the door, he is brained by a loose beam; when he leans against another door, he finds himself half-drowned in the creek; when he takes up a broom, the roof, which it has been supporting, falls in. He comes dashing out of the dog house for his morning dip and alights in two inches of water in a ditch.

Religion comes off a trifle scorched in the scene where the minister’s wife, suffering from gas on the stomach, comes to visit the prisoners in jail. There are hundreds of little characteristic bits which build up the picture of Mr. Common Man faced by life. To the gratification of the world, Chaplin brings back his old roller-skating act, teetering crabbily on the edge of the rotunda in the department store where he is spending the night (one night only) as a watchman. He gives the waif (splendidly played by Paulette Goddard) her first good meal in months and a night’s rest in a bed in the furniture department. His desire to get away from the cruel world is so strong that he deliberately gets himself arrested, stoking up with two full meals in a cafeteria and then rapping on the window for the attention of a policeman when he nears the cashier’s desk.

From the standpoint of humor, however, the picture is not a steady roar. The reason for it is simple: You can’t be jocular about such things as starvation and unemployment. Even the people who are least affected by the misery of others are not comfortable when they see it. They are not moved by it; they resent it. “What do you want to bring up a lot of things like that for?” That Chaplin has been able to present a comic statement of serious matters without perverting the problem into a joke is all the more to his credit. It is a triumph not only of his art but of his heart. What his political views are, I don’t know and don’t care. He has the feelings of an honest man and that is enough. There are plenty of people in Hollywood with honest feelings but with the distributive machinery in the hands of the most reactionary forces in the country, there is no possibility of honesty in films dealing with current ideas. It is this fact which makes Modern Times such an epoch-making event from our point of view. point of view. As I say, only Chaplin could have done it. Except for the one scene I have mentioned, he has never sacrificed the strict line of the story for a laugh. That is so rare as to be practically unknown in films. Modern Times itself is rare. To anyone who has studied the set-up, financial and ideological, of Hollywood, Modern Times is not so much a fine motion picture as an historical event.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1936/v18n08-feb-18-1936-NM.pdf