Leonard Abbott, even with only one cryptic reference to Edward Carpenter’s pioneer role in advancing gay freedom, provides a wonderful introduction as to why Carpenter and his writings had such a profound impact on a generation of radicals, including in the Socialist movement to which Carpenter belonged.

‘Edward Carpenter and His Message’ by Leonard D. Abbott from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 1 No. 5. November, 1900.

THERE is no single feature in the literature of our times that is more profoundly significant and interesting than the revolt against modern society. A Tolstoi in Russia, a Zola in France, an Ibsen in Norway, a Howells in America, have all made their art the vehicle of a social message. In England this tendency is especially marked. We have seen John Ruskin and William Morris, two of the most striking literary figures of the Victorian era, break away from the old traditions, and throw the whole weight of their influence into the struggle for better social conditions. In the England of to-day we see a spectacle equally remarkable. We find communism—that bugaboo of the respectable classes, that very embodiment in the popular mind of all that is accursed—openly espoused by a group of literary men whose genius is recognized all over the world.

Edward Carpenter is perhaps the most talented member of this group, and he strikes a note in contemporary literature that is as unique as it is inspiring and beautiful. Carpenter stands for democracy in its fullest and broadest sense—democracy which represents not merely political forms, but which penetrates to the very roots of society. He turns with horror from the life of to-day, with its degradation of human life, and its subordination of beauty to profit, and pictures the days of the future, when commercialism has been supplanted by communism. In his dream of the society which is to be he realizes his ideal of brotherhood of art, of nature-love.

Thirty years ago Edward Carpenter, while at Cambridge University, came under the influence of the Rev. F. D. Maurice, the Christian socialist, and entered the Church of England. He relinquished his orders, however, and for some years was a university extension lecturer on art, music and science in the north of England. In 1877 he visited the United States and became acquainted with Walt Whitman. He had already fallen deeply beneath the spell of this great democratic thinker, and upon his return to England he took to farm life at Millthorpe, near Sheffield, and began to think out his “Towards Democracy.” Much of this book was written in the open air, and it breathes the spirit of the fields and flowers. “Towards Democracy” and its sister poems, were published in 1883 and were quite startling in their unconventionality. Carpenter had become saturated with the Whitman spirit. He used in his poems the same rough, unfettered form, and held out to the world the same democratic ideal. “Leaves of Grass” finds its transatlantic prototype in “Towards Democracy.” The poem “Towards Democracy” is a wonderful revelation of Carpenter’s personality. In a series of seventy dramatic stanzas, which sweep the reader along with impetuous force, the poet touches every emotion in human life. He associated himself with the lowest and vilest, as with the noblest; he hurls anathemas against modern society; he writes passionately of love, and of kinship with nature and animal life; he voices the hope of a new era of fraternity and beauty.

In one of the most striking passages of “Towards Democracy” Carpenter gives a panoramic survey of England. With a master hand he paints the picture he sees before him. Rivers, mountains and cities all pass beneath his gaze:

“The beautiful grass stands tall in the meadows, mixed with sorrel and buttercups; the steamships move on across the sea, leaving trails of distant smoke. I see the tall white cliffs of Albion.

“I smell the smell of the new-mown grass, the waft of the thought of Death—the white fleeces of the clouds move on in the everlasting blue—with the dashing and the spray of waves below…

“I see the sweet-breathed cottage homes and homesteads dotted for miles and miles and miles. I enter the wheelright’s cottage by the angle of the river. The door stands open against the water, and catches its changing syllables all day long; roses twine, and the smell of the woodyard comes in wafts…

“The oval-shaped manufacturing heart of England lies below me; at night the clouds flicker in the lurid glare; I hear the sob and gasp of pumps and the solid beat of steam and tilt-hammers; I see streams of pale lilac and saffron-tinted fire. I see the swarthy, Vulcan-reeking towns, the belching chimneys, the slums, the liquor shops, chapels, dancing saloons, running grounds, and blameless remote villa residences.”

Finally comes the climax: “I see a land waiting for its own people to come and take possession of it.”

Edward Carpenter writes as one stifled by the artificiality of modern life. In fiercest words he lays bare the shams and hypocricies which he sees around him. He lashes “the insane greed of riches, of which poverty and its evils are but the necessary obverse and counterpart,” and “smooth-faced Respectability, so luxurious, refined, learned, pious—yet all out of other men’s labor.” He laughs at “ideas of exclusiveness, and of being in the swim; of the drivel of aristocratic connections; of drawing-rooms and levees and the theory of animated clothes pegs generally; of helplessly living in houses with people who feed you, dress you, clean you and despise you.” He sees a nation that has far departed from the laws of nature and of healthy life; ever is he haunted by the vision of the world that might be and thoughts of “the free sufficing life—sweet comradeship, few needs and common pleasures.” I propound a New Life to you,” he exclaims, “that you should bring the peace and grace of Nature into your own daily life—being freed from vain striving.”

In a poem entitled “After Civilization” Carpenter thus beautifully presents the idea of the unfolding of the new society:

“Slowly out of the ruins of the past—like a young fern-frond uncurling out of its own brown litter—

Out of the litter of decaying society, out of the confused mass of broken-down creeds, customs, ideals;

Out of distrust and unbelief and dishonesty, and fear, meanest of all (the stronger in the panic trampling the weaker underfoot);

Out of the miserable rows of brick tenements’ with their cheap jack interiors, their glances of suspicion, and doors locked against each other;

Out of the polite residences of congested idleness; out of the aimless life of wealth;

Out of the dirty workshops of evil work, evilly done;

I saw a New Life arise.”

In his essays Edward Carpenter has written definitely of the economic structure of the ideal society, but in his poems he rather gives us hopes and aspirations. He speaks of the spirit of mutual service and dependence under Communism, in which each will do the work before him “doubting no more of his reward than the hand doubts, or the foot, to which the blood flows according td the use to which it is put.” This conception of a social order based upon the idea “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need” is supported by references to the Law of Equality, which Carpenter interprets in this way:

“If you think yourself superior to the rest, in that instant you have proclaimed your own inferiority:

And he that will be servant of all, helper of most, by that very fact becomes their lord and master.

Seek not your own life—for that is death;

But seek how you can best and most joyfully give your own life away—and every morning for ever fresh life shall come to you from over the hills.”

In another poem he writes of “the outspread pinions of Equality, were on arising Man shall at last lift himself over the Earth and launch forth to sail through Heaven.” The stanzas entitled “The Curse of Property” are a tremendous indictment of existing property claims, and leave no doubt as to the trend of Carpenter’s communist teachings.

This truly remarkable book of poems strikes a note of intense realism, Edward Carpenter accents all the facts of life, “nothing blinked or concealed,” he makes himself the mouthpiece of the “vast unfettered human heart” in its every manifestation. But he is also saturated with an equally intense idealism. He lives and writes in the present, but his hope is in the future.

Edward Carpenter has given practical expression to his ideals by taking part in the Socialist agitation of England. About the year 1883, just after the first English Socialist society had been founded, and while William Morris and H.M. Hyndman were carrying on a vigorous propaganda in London, Carpenter was drawn into the Socialist movement. It was with his money that “Justice,” the first English Socialist paper, was started, and he both wrote and lectured on behalf of the Social Democratic Federation, When William Morris seceded from the Federation and founded the Socialist League, Edward Carpenter showed himself in sympathy with the new body, and contributed to Morris’ revolutionary journal, “The Commonweal.” He compiled and published during this period an interesting Socialist song book, with music, and shortly after some of his Socialist lectures and articles were issued under the title of “England’s Ideal.” In 1889 “Civilization, Its Causes and Cure,” and other scientific and social essays were published in book form, and a year later he wrote a long account of his travels in India, which he called “From Adam’s Peak to Elephanta.” During recent years Carpenter has given much attention to sexual problems, and a book entitled “Love’s Coming of Age” sums up his thoughts on love and marriage. Carpenter’s last contributions to literature are a series of essays on art and its relation to society, published under the name “Angels’ Wings,” and a translation of “The Story of Eros and Psyche,” from Homer’s Iliad.

In the essay, “Civilization, Its Causes and Cure,” we touch the heart of Edward Carpenter’s life philosophy. To the majority of readers the title will seem a strange audacity—the more so since Carpenter looks upon civilization in no mere humorous sense, but quite soberly and seriously, as a disease. He instances its unhealthiness and retinue of doctors, its feverish spirit of unrest, and its miserable poverty; comparing these features with the normal life of the more developed savage races. Carpenter lays great stress on the moral and physical qualities which humanity has lost in its progress from barbarism to civilization, and while he is far from advocating a mere return to first principles, he shows quite clearly that civilization has not meant all gain. He also lays emphasis on the fact that the men of to-day have almost wholly abandoned nature, and “disowned the very breasts that suckled them.” “Man,” he says, “deliberately turns his back upon the light of the sun, and hides himself away in boxes with breathing holes (which he calls houses), living ever more and more in darkness and asphyxia, and only coming forth perhaps once a day to blink at the bright god, or to run back again at the first breath of the free wind for fear of catching cold!” “He is the only animal,” he adds, in another passage, “who, instead of adorning and beautifying makes nature hideous by his presence. The fox and the squirrel may make their homes in the wood and add to its beauty in so doing; but when Alderman Smith plants his villa there, the gods pack up their trunks and depart; they can bear it no longer. The bushmen can hide themselves and become indistinguishable on a slope of bare rock; they twine their naked little bodies together, and look like a heap of dead sticks; but when the chimney-pot hat and frock-coat appears, the birds fly screaming from the trees!”

Edward Carpenter lays the blame for modern conditions chiefly on the institution of private property, and its accompanying system of class government. Property, he claims, has divorced man (1) from nature, (2) from his true self, (3) from his fellows, At the same time he realizes that the development of modern society is working out its own downfall. The industrial tendency to-day is ever toward co-operation and communal ownership, as opposed to private competition, and as Carpenter claims, the only logical culmination appears to be communism— that is, public ownership of the means of life. He claims that such conditions would insure a secure and brotherly life for all, and that the human spirit, freed from the bonds of a sordid commercialism, would soar to heights undreamed of to-day. He believes that there would be an almost universal return to nature and simplicity. “Then,” he says, “when our temples and common halls are not designed to glorify an individual architect or patron, but are built for the use of free men and women, to front the sky and the sea and the sun, to spring out of the earth, companionable with the trees and the rocks, not alien in spirit from the sunlit globe itself or the depth of the starry night— then, I say, their form and structure will quickly determine themselves, and men will have no difficulty in making them beautiful. In such new communal life near to nature—its fields, its farms, its workshops, its cities—we are fain to see far more humanity and sociability than ever before; an infinite helpfulness and sympathy, as between the children of a common mother.”

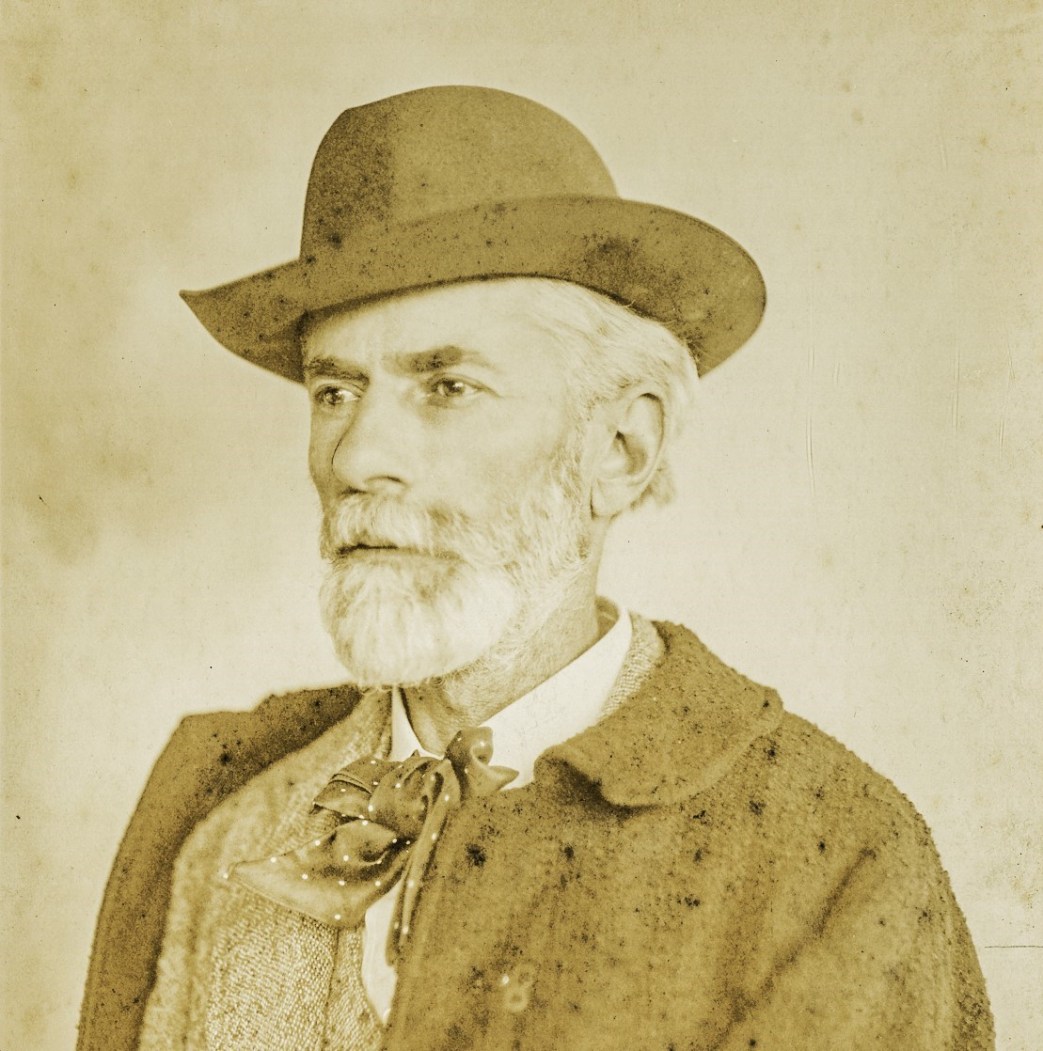

Edward Carpenter has much in common with two of America’s greatest sons, Henry D. Thoreau and Walt Whitman. He shares with both the passionate nature—love, amounting almost to religion; with both he revolts from the cumbrous machinery of a complex civilization. In the same way that Thoreau retired to his hut by Walden, Carpenter spends his days at a farm in a beautiful Yorkshire dale, and here he lives a simple country life, working day by day on the soil and alternating manual with intellectual toil. Occasionally also he lectures throughout England. He has entered into relations of true fellowship with the laboring people around him, who come to him to discuss their daily affairs, their trials and their hopes. Edward Carpenter’s personality is delightful. He is small and well-proportioned and his thoughtful face is one of singular beauty, with brown beard and expressive eyes.

“To meet Edward Carpenter,” says one of his friends, “or to listen to one of his characteristic lectures on social questions, is to find oneself in touch with a man who is absolutely free from the fetters of conventionality. Here in the human world is that which makes you think of nature—a wave of the sea, an oak on the free hillside; it is nature become intelligent and human, or man become a part of nature and still man! He does not strike one as brilliant, or as learned, or as eloquent, but as something entirely natural and fresh and unconstrained. Some happy secret is his, and life is made beautiful and calm and full of joy therewith.”

Perhaps Edward Carpenter told the world his “happy secret” when he wrote the following poem:

“Sweet secret of the open air—

That waits so long, and always there, unheeded.

Something uncaught, so free, so calm, large, confident—

The floating breeze, the far hills and broad sky;

And every little bird and tiny fly or flower

At home in the great whole, nor feeling lost at all or forsaken,

Save man—slight man!

He, Cain-like from the calm eyes of the Angels,

In houses hiding, in huge gas-lighted offices and dens, in ponderous churches,

Beset with darkness, cowers;

And like some hunted criminal torments his brain

For fresh means of escape, continually;

Builds thicker, higher walls, ramparts of stone and gold, piles flesh and skins of slaughtered beasts,

’Twixt him and that he fears;

Fevers himself with plans, works harder and harder,

And wanders far and farther from the goal.

And still the great World waits by the door as ever,

The great World stretching endlessly on every hand, in deep on deep of fathomless content—

Where sing the morning-stars in joy together,

And all things are at home.”

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v01n05-nov-1900-ISR-gog-Wisc.pdf