Matilda Rabinowitz, paid I.W.W. organizer sent to Detroit to bring the One Big Union into the auto factories, reports on conditions in the neighborhoods and plants of ‘Motor City.’ The week following this article, on June 17, 1913, thousands of workers walked out of the Studebaker plant, joined by the Timken Axle plant workers led by Rabinowitz. The first auto strike in history had begun.

‘The Automobile Industry and the I.W.W. in Detroit’ by Matilda Rabinowitz from Solidarity. Vol. 4 No. 23. June 14, 1913.

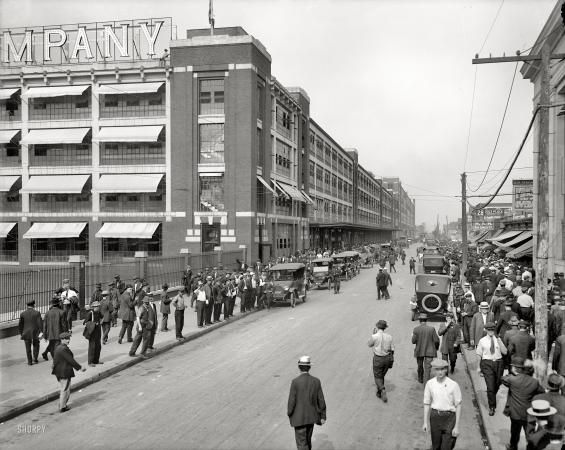

Detroit, which has come into prominence as the largest center in manufacturing automobiles within the past ten years, has at the same time been productive of industrial and social conditions for the working class, of which many cities with longer manufacturing pedigrees would be ashamed of.

A few years ago when automobile factories sprung up in Detroit very suddenly labor became scarce. The capitalists in control of the then embryonic industry began to look for slaves to produce automobiles.

All through the East advertisements were scattered, and thousands of workers were daily reading of the wonderful opportunities awaiting them in Detroit. Every worker had a chance to hold the best job forever; to own his home; to ride in his automobile; to even become a stockholder in the factory!

The industry was new, the wages e big, conditions were brilliant. e workers took the bait and came. Thousands began to pour into Detroit every year. There was a steady flow from the industrial towns of the East and the farm districts of the Middle West. The capitalists never stopped representing Detroit as a veritable Mecca, and the automobile industry as a gold mine, until they filled their factories with slaves to overflowing, and from a small city it grew to a population of 250,000.

Having grown so rapidly, as rapidly as the industry and the millionaires it made, Detroit presents today not as the capitalists would have it known throughout the country-“A city of opportunities” -but a city of rooming houses, cheap lunch rooms, and still cheaper amusement places. It has a large floating population of men between the ages of 18 and 35, people who cannot afford decent living conditions, and exist in overcrowded tenements, with nickel shows, saloons, and brothels adjacent. The enormous rents exacted by the landlord sharks make it impossible for the man with a family to find a dwelling place to correspond with his wages, and the average wage, as figured by the State Labor Bureau of Michigan, is about $2 a day in Detroit.

Wages are low, the cost of living high, general conditions are those of any other congested industrial city, if not worse, but still Detroit is held up as a model city throughout the country, and fresh labor power keeps pouring in, only to be ground down to the same level as those who came before.

When the I.W.W. made its advent into town the factory owners immediately began to see danger in it, and treated it accordingly. Speakers and organizers were arrested, the capitalist press howled, about the black deeds of it, and gave it editorial space; the police department was kept busy; generally there was one grand shakeup in the apparently placid “city of opportunity,” and the “good understanding between capital and labor” sham was brought to light.

The exploited, Taylor-systematized and efficiency-driven workers in the automobile industry began to wake up to the horrible iniquities of the wage system.

Noon-day agitation at the factories proved successful. In one of the largest factories the workers abandoned the daily handball playing within the factory and on the baseball field, and other innovations to keep the slaves contented, and came out every noon waiting for the speakers. In another the management threatened to cut down the nooning to thirty minutes, and in all of them workers are being fired for talking unionism at work, and even for talking to the speakers. The meeting hall of the I.W.W. is filled with spies for the companies, making it necessary to dispense with the reading of applicants names, and substituting numbers instead. Scores of workers are joining at every meeting, and new recruits soon become agitators within the factories. The manufacturers are frantic, and the kept press is writing, crying to the high heavens, warning the workers against the “I Won’t Work” movement. The Merchants and Manufacturers’ Association, in its annual meeting, held in Detroit in May, passed resolutions denouncing the I.W.W. as a menace to the existing system (how well they know) and ap- pealing to all “God loving,” “patriotic” citizens to rally against the “off-shoot of the anarchist-syndicalist movement of Europe.”

The I.W.W. has cheerfully accepted this recognition by the M. & M. and made fine capital out of it. The agitation at the factories is still going on, and it is hoped that before the summer is over the automobile workers of Detroit will have a big organization and the power to demand more wages, shorter hours, and with a higher standard of life and more time to think, prepare themselves for the final conflict which will end wage slavery.

The most widely read of I.W.W. newspapers, Solidarity was published by the Industrial Workers of the World from 1909 until 1917. First produced in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and born during the McKees Rocks strike, Solidarity later moved to Cleveland, Ohio until 1917 then spent its last months in Chicago. With a circulation of around 12,000 and a readership many times that, Solidarity was instrumental in defining the Wobbly world-view at the height of their influence in the working class. It was edited over its life by A.M. Stirton, H.A. Goff, Ben H. Williams, Ralph Chaplin who also provided much of the paper’s color, and others. Like nearly all the left press it fell victim to federal repression in 1917.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/solidarity-iww/1913/v04n23-w179-jun-14-1913-solidarity.pdf