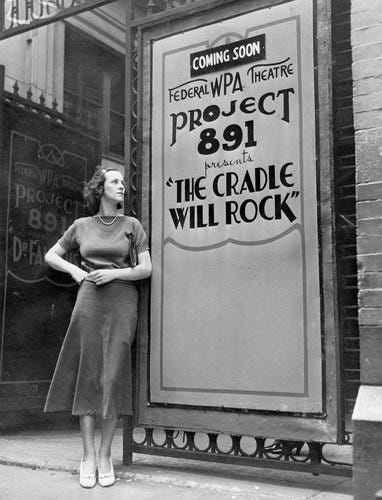

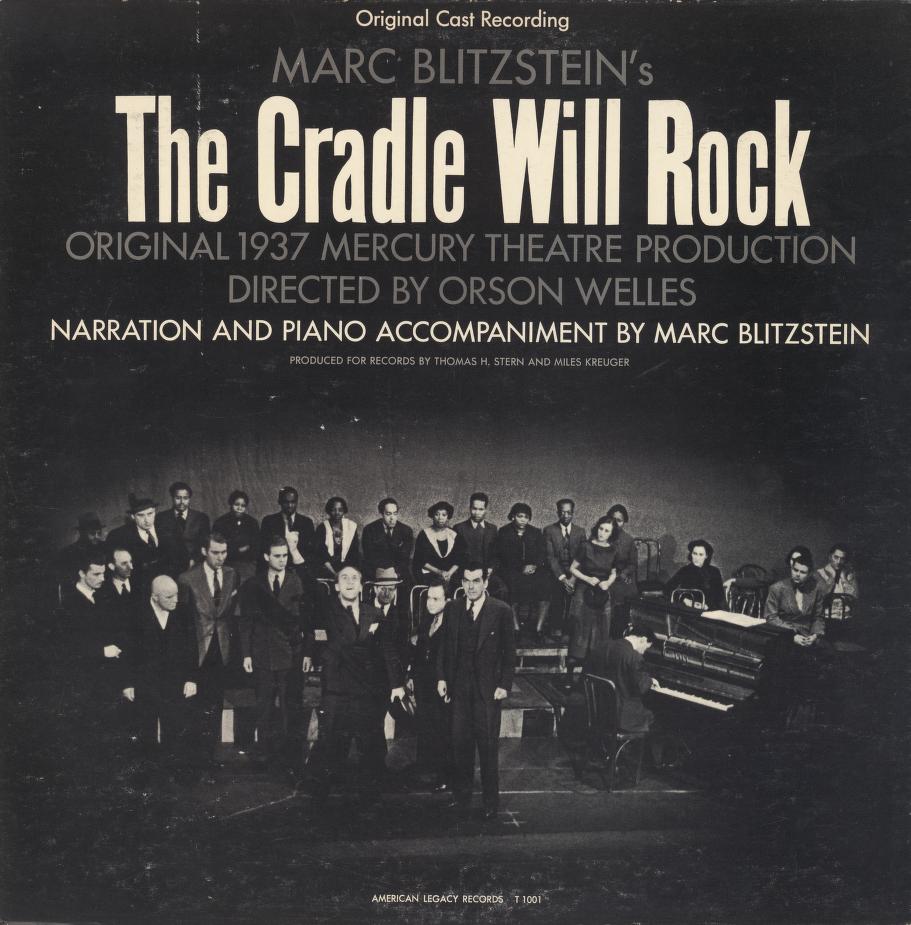

Famously locked out of its first performance, The Cradle Will Rock, written by New Masses regular Marc Blitzstein and directed by a 22-year-old Orson Welles, was the first musical to have a cast recording made. Review below, here is a link to the original album to listen for yourself.

‘The Phonograph Rocks the Cradle’ by Roy Gregg from New Masses. Vol. 27 No. 9. May 24, 1938.

TWO or three months ago I was yelping for a recording of The Cradle Will Rock, more in hope than faith, and scant hope, when I heard that the Mercury production was going to close. The show itself was something of a miracle (“the most exciting evening of theater this New York generation has seen”), but the transfer to discs—even after its sensationally successful run-called for plenty of miracle-making. The problems of expense and mechanical difficulties to be surmounted were tough enough, but the fundamental difficulty was, who had the nerve to tackle it? Some individuals in the major companies were interested but lacked nerve and authority. The best they could do was to suggest dance-band versions of some of the hit tunes, with, of course, some of the edges taken off the too biting texts. But if Broadway has its Mercury Theatre and Mr. Welles, the phonograph has Musicraft Records and Messrs. Rein and Cohen. And we have them to thank for the handsome red and black album-set of seven discs with a permanent performance of the Mercury production of The Cradle, intact with cast, Blitzstein and his piano, and the original musicodramatic dynamite.

The phonograph has its limitations when it attempts opera and drama, but The Cradle is no ordinary opera or drama. The very style of production (adopted of necessity, but proved to be ideal) is admirably suited to loudspeaker performance, and just as the unset stage and the minimum of stage business concentrated attention on the show itself, on records we lose nothing but that minimum of pantomime and “action,” leaving the field clear for the true inner action unfolded in speech and song. A few condensations had to be made, of course, but no important material has been omitted, and the slight gaps are bridged by Blitzstein’s running commentary.

The first scene is clipped a bit, skipping the dialogue between the Moll (Olive Stanton) and the Gent, Moll, and Dick (Guido Alexander), but that brings us all the quicker to the roundup of the Liberty Committee and the plunge into the first case, that of Reverend Salvation (Charles Niemeyer) and his 1915-16-17 sermons-record-sides two and three-the latter completed with Junior (Maynard Holmes) and Sister (Dulce Fox) Mister’s luscious “Croon Spoon.” Side four brings in Mr. Mister (Ralph MacBane) and Editor Daily (Bert Weston) and their apostrophe to the “Freedom of the Press,” and side five completes the scene with the incomparable “Honolulu.” The Drugstore episode (Druggist, John Adair; Steve Howard Bird; Sadie, Marian Rudley; and Gus, George Fairchild) and the poignant “Love Song” take up sides six and seven, with the next two presenting the riotous scene of Mrs. Mister (Peggy Coudray) and her proteges Yasha (Edward Fuller) and Dauber (Jules Schmidt).

Side ten brings us back to the Nightcourt and one of the musical high points of the work, the “Nickel” song by the Moll. Larry Foreman (Howard Da Silva) enters on side eleven with the title song-and incidentally, Mr. Da Silva may have been criticized for overacting a bit on the stage, but his recorded performance is an irreproachable masterpiece of blended subtlety and power. Mr. Blitzstein gives us the gist of the Faculty room and Specialist-Mister scenes, leading up to another peak, “Joe Worker,” superbly sung by Ella (Blanche Collins) on side thirteen; and the work ends with the climactic finale intact.

One can’t be sure just how the records will affect those who didn’t see the show: they may find the beginning a little jumpy, and the end is not as likely to sweep them off their feet as that of the stage production. But I don’t see how they can fail to get the meat of the work, be shaken right down to the heart and guts by its gripping drive, as dynamic if not even more compelling on these miraculously evocative discs than it was on the stage. And those who know the show, who have heard it once or a dozen times, will find new subtlety and strength in it every time one of these records spins on its turntable. Musicraft Album Number Eighteen, ready now; $10.50, and the best investment you ever made in American music, entertainment, and soul stimulation.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1938/v27n09-[plus-Special-Debate-Section]-may-24-1938-NM.pdf