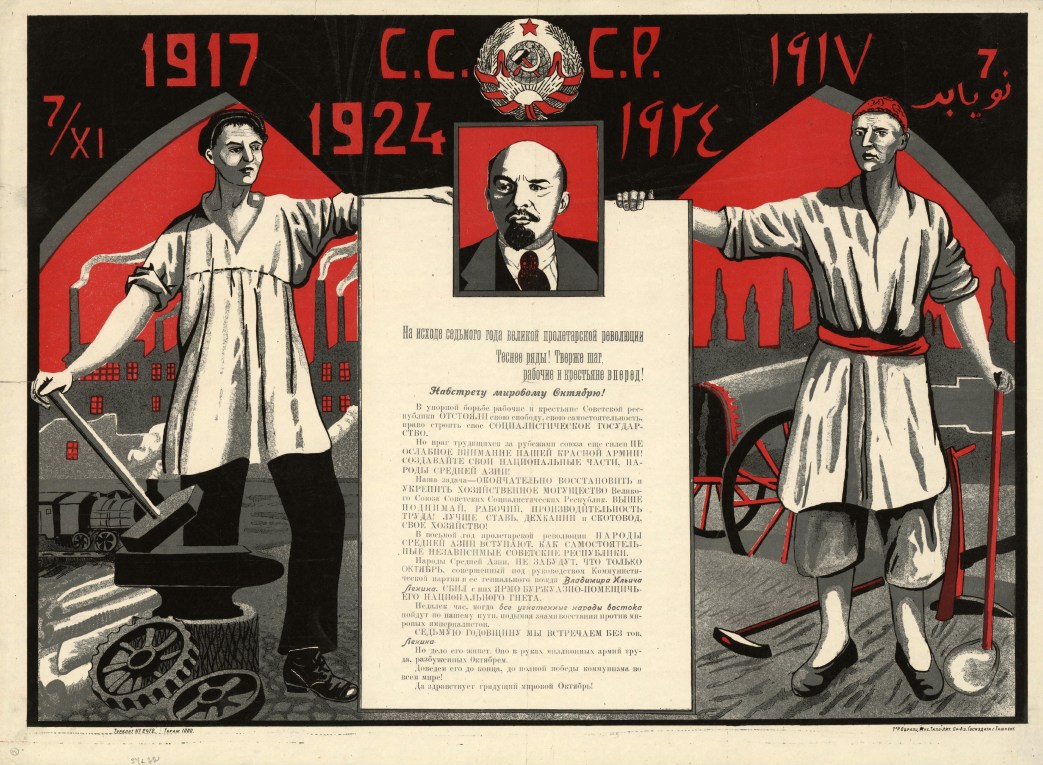

Written between Lenin’s January 1924 death and the Bolsheviks’ 13th Party Congress, the first without Lenin, that May, this substantial piece by Karl Radek details Radek’s own history with Lenin as well as Lenin’s larger political history. The debate over Lenin’s legacy and matel began before Lenin’s death, and Radek’s article should also be seen as part of the so-called Literary Debate that occurred in the Party that summer and fall. Spread over two issues of The Liberator, Radek places particular emphasis on Lenin’s role in founding the Communist International and his activity at its first four Congresses. Transcribed here for the first time.

‘The Life and Work of Lenin’ by Karl Radek from The Liberator. Vol. 7 Nos. 4 & 5. April & May, 1924.

FOR the first time in the history of humanity the news of the death of a political leader will not only spread throughout the entire world, but will even cause the hearts of millions of people of different lands and nations to tremble. There are lands where millions will mourn him, in some, hundreds of thousands, and in others perhaps only a scattered few; but there will not be a single nation where some persons will not say on January 22: “My leader is dead!”

All of the bourgeois revolutions had an international significance, not only because each one of them shook the foundations of complex international relations, not only because each one of them aroused the conscience by means of the progressive step it involved, but also because in all bourgeois revolutions the more advanced elements wished to go beyond the bounds of their nation, beyond the bounds of aspirations circumscribed by the borders of their territories. At the time of the English revolution a small group of communists, dreaming of the new millennium of human happiness, went to the extent of advocating war against capitalist Holland, and were preparing to carry their communist faith far into the domain of the English Channel. During the French revolution the struggle against the monarchy aroused in the hearts of many champions, with Anacharzis Kloats at their head, a feeling of internationalism, a feeling of absolute need of international overthrow of monarchy and feudalism. Likewise the revolutionary movement of the bourgeoisie of one country aroused the sympathy of the advanced elements of the bourgeoisie of another country. But this meant more than sympathy.

The bourgeois revolutions took place at a period when the economic balance of different countries varied so greatly that every bourgeois revolution became a national one. Each was unable to proceed beyond the bounds of its own territory. Moreover, because the revolutions were bourgeois in character each strove to gain certain advantages for its particular nation and therefore could not arouse a feeling of solidarity in others. The English revolution threatened the sovereignty of the bourgeoisie of Holland. The French revolution, bringing on its bayonets freedom from the yoke of feudalism, simultaneously threatened the German people with national disintegration and forced even those who remained loyal to the cause of the revolution and understood its greatness, to rise in rebellion against it in the struggle for the independence of their country. The worshippers of French revolution in Germany, Greisenau and Scharnhorst, became at the same time the organizers of a war of liberation from the Napoleonic yoke.

The Russian revolution, the first victorious proletarian revolution, became proletarian only because the development of capitalism reached not only to the Ural mountains and the summits of the Caucasus, but even to the shores of the Pacific Ocean. The capitalism which prepared the ground for a proletarian revolution in backward Russia, made the Russian revolution the champion of international revolution. And when the torch of the Russian revolution had been kindled it illumined the whole world, and it continues to do so, inflaming the hearts of millions of people throughout the universe. The German worker, informed by means of books and newspapers about the days that shook the world, and the Chinese coolie who learned of the Russian revolution in the saloons of San Francisco while conversing with English sailors, the Mexican laborer struggling against his own feudal lords and the American plutocracy, the Hindu peasant to whom the news of the Russian revolution came through the hostile telegrams of Reuter-each of these considered the great Russian revolution to be his own, the beginning of his own liberation.

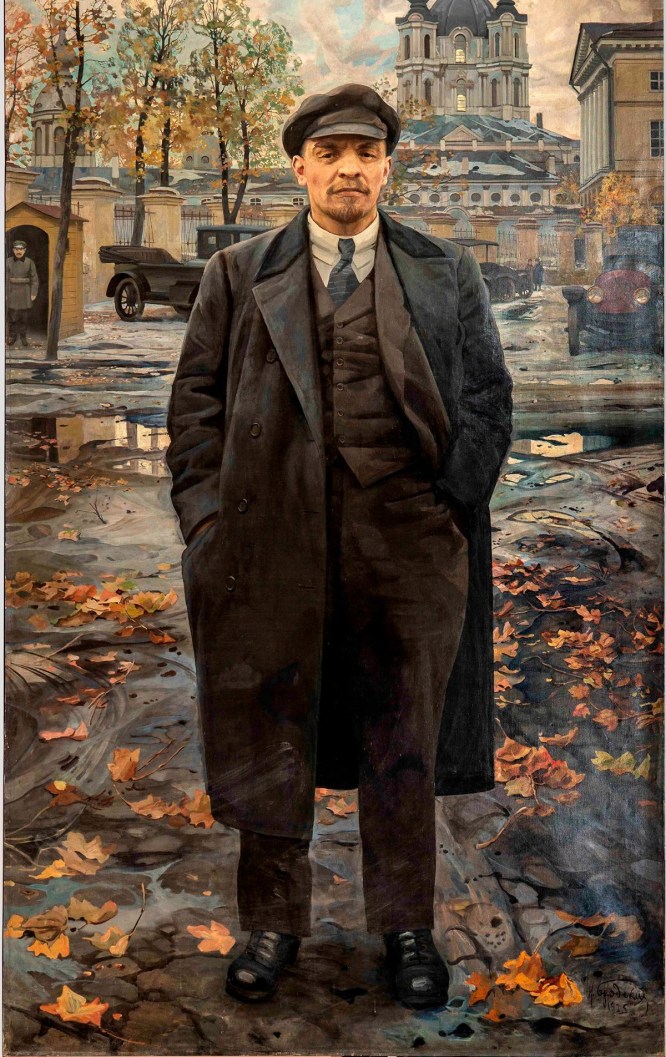

The standard bearer of the Russian Revolution-Lenin-became the standard bearer of the world revolution. He became the symbol of a new era in human history, the era of the liberation of the toiler, the era of the struggle of the working class for the re-creation of the world on a new basis. The death of Bebel aroused grief in the hearts of millions of workers in Europe, but it was unable to shake the proletariat and the peasantry of the whole world, for the German Social Democracy had not outgrown the limits of the capitalist world. The death of Lenin will shake these millions, will force them to think of the past and of the difficult road which still lies before us and which must be cleared by the axe with very great difficulty. Lenin raised the standard of the revolt against world capitalism. It is because of this that the death of Lenin unites in grief all those who struggle against the yoke of the bourgeoisie.

The death of Lenin will give an impetus to proletarian thought throughout the world. In all countries the proletariat learned to fight from the mere fragments of Lenin’s thought which had reached them in the form of our leaflets and resolutions. Verifying these thoughts in their own experiments and seeing in them the truth concerning their own lives, they were assured; they knew that at the helm of the ship of International Revolution stood this genius of the international proletariat. And they entrusted themselves to his leadership. But he is no more! The minds of all who think in the rank and file of the labor movement, are busied with the thought of how to absorb the life and work of Lenin; how to find in his writings the weapons for the struggle, and how to learn to control this weapon independently. There is nothing more convincing than the words which a German Communist uttered upon receiving the news of Lenin’s death: “Don’t give us the select works of Lenin, give us, in the chief European languages, all the works of Lenin, in order that we may assimilate his thoughts and methods through his own works.”

Many years will pass before it will be possible to erect this monument to Lenin-at least in the chief countries where the labor movement is prominent; until we shall by diligent study of the life and work of Lenin be able to help the European worker to absorb his entire inheritance.

In the meantime, the problem of the communists is how to present at least in very general outlines the historic role of Lenin and to give a skeleton of his thought.

Lenin as the Founder of the First Proletarian Government

The teachings of Marx are written in the books created by him. His correspondence is a sufficient commentary on his compositions. Lenin left dozens of volumes. When his correspondence is collected it will add additional dozens of volumes. But the chief commentary on Lenin’s teachings is the work of Lenin, his labor, the creation of the Communist Party of Russia and the struggle of the party for power. These are the methods by means of which the proletariat held the power under unheard of conditions-the method which Lenin bequeathed to the Russian proletariat, not only as a means of retaining power, but also as a means of solving problems; the methods in whose name the working class of Russia took the power into its own hands.

Marx took part in the revolution of 1848 in Germany. But because of the weakness of the proletarian elements, he could not play a decisive role. The revolution of 1848 in Germany was an historical abortion. It arrived too late to be successful as a bourgeois revolution and too early to be headed by the proletariat. The revolution of 1848 was followed by decades of reaction, where Marx could be no more than an observer, studying the mechanism of the bourgeois world. To relieve this reaction came the epoch of nationalistic wars, in which again the proletariat could not become the leading force. Because of this it was impossible for Marx to take the leading part. Soon the meteor of the Paris Commune illumined the horizon. Only the genius of Marx could understand the meaning of the ephemeral phenomenon. And even here it would be needless to speak of the role Marx played as a leader.

After the Paris Commune and until the death of Marx, reaction reigned in Europe. The revolutionary problems of the bourgeoisie were solved in the West. The proletariat, however, began to line up its forces carefully and slowly. They assembled in small groups in various countries. Their timorous movements could not be conducted from one center. The entire genius of Marx was exhausted in the effort to learn the fundamental laws governing the development of the bourgeois world and the proletariat’s relation to it. Marx’s genius could not be tested in the fire of civil war and make him the ingenious leader of the revolution.

Lenin stood firmly on the principles of Marx’s teachings, which he understood more profoundly and more thoroughly than any other of Marx’s disciples. But Lenin had from the first days of his career prepared himself for the role of a political leader of communist revolutions. His whole life was devoted to the analysis of a problem which was not solved until 1917, viz., to the preparation for the great breach in the ranks of the international bourgeoisie which took place in October, 1917. Thirty years ago this spring the young Lenin in his work “What is this-the Friends of the People” wrote: “The social democrats direct all their attention and activities to the working class. When its advanced representatives shall have assimilated the ideas of scientific socialism and the idea of the historic role of the Russian worker, when all these ideas shall have received wide publicity and there will be formed among the workers permanent organizations that will help in their present desperate economic strife and will advance the conscious class struggles-then the Russian worker, rising at the head of all democratic elements, will crush absolutism and lead the Russian proletariat, together with the proletariat of the entire world, along the path of the open political struggle to the victorious communist revolution.”

The study of Lenin’s teachings regarding the communist revolution involves above all the knowledge of the method employed by Lenin, as the leader of the struggle of the Russian proletariat for power.

All were struck by the unheard-of faith with which Lenin appeared as a statesman, as a leader of the proletarian party. Some ascribed this faith to his tremendous will power, which made him a born leader. Others found the source of Lenin’s faith in his firm belief in socialism. Strength of will, however, does not always unite people; sometimes it repels them, especially when the test of time shows that will to be leading itself and others into the wrong path. Lenin’s power as a leader consisted in his ability to impress his party comrades with the conviction that his would always lead them to the true historical course.

This correct path he was unable to find in socialism. Kier Hardie, the leader of the English reformers, who led the English proletariat into the wrong path, had unshaken belief in socialism; likewise Jean Jaures, the leader of French reformism, had profound faith in socialism, as did also Victor Adler, the sanest man of the Second International, who had brought the Austrian proletariat to the brink of social patriotism. But not one of the above mentioned stood the historical test, despite their sincerity. Socialism does not become a religion; it becomes a science of the conditions of the proletarian victory. The source of the iron faith of Lenin was the fact that he, as no other of Marx’s disciples, thoroughly absorbed Marx’s social teachings, and that he applied them as had none of the other disciples of the father of socialism. Occupied by the practical work of forming a proletarian party in Russia, and by its leadership, Lenin left very few works de- voted to the general basis of Marx’s teachings. It is sufficient to note how Lenin in his youthful work raised problems in historical materialism; it is enough to compare his question with the same problem presented in the works of Plekhanov and Kautsky of the same period, to see how Lenin solves the problems of Marxian theory. Two or three of his pages taken at random in the pamphlet he issued at the time of his discussion regarding the trade unions and devoted primarily to a series of dialectics and eclectics, show how modest Lenin was when he called himself the pupil of Plekhanov. Lenin was a great independent Marxian thinker. This quality was the prerequisite which permitted this powerful man to become the chief political leader of the international proletariat. Lenin the thinker, Lenin the political leader of the Russian revolution, grew up in an environment which placed the problem of revolution as a problem of political struggle. This immediately permitted him to outgrow the other disciples of Marx. Lafargue was brought up in a petty bourgeois land which had passed through the storm of three revolutions and in which capitalism had not yet paved the way for a new proletarian uprising. The great talent of Lafargue could not evolve itself into genius.

Kautsky, the first after Engels and Marx to attempt to accept Marxism independently, could utilize it only in the study of the history of society. Actually, however, in the problems of the German movement, Marxism served him as a means of impressing the proletariat that it was impossible either to outflank the class enemy or to step over him; that it is necessary to gather slowly the forces for the decisive battle. This decisive battle was so distant that when Kautsky in his works on the social revolution timidly arrived at the problem of seizing power, the outlines of his problem were so unintelligible even to himself that he overlooked one of the chief factors of the proletarian revolution, the question of where the victorious proletariat was to obtain its bread the day after its victory.

Plekhanov, the brilliant exponent of Marx’s teachings, the able defender “Against any Kind of Critics,” lived far away from the sources of the storm, far from Russia. And his entire deep interest in the revolutionary struggle in Russia seemed insufficient to necessitate the application of all the power of his mind to the study of the practical problems associated with the revolutionary struggle of the Russian proletariat. There is nothing more characteristic than the fact that after “Our Disagreement” Plekhanov did not make a single effort at any detailed study of one of the chief problems of the Russian revolution-the agrarian problem.

Lenin as a theorist, Lenin as a political scientist, devoted himself at the very outset of his study, to the chief field of action of the Russian proletariat and the main forces which must needs participate in the Russian revolution. A comparison of the agrarian problems as presented by Kautsky, Kshivitsky and Comper Morel on the one hand, and as presented by Lenin on the other, shows clearly not only the difference of the economic conditions of Western Europe from Russia, not only the peculiarities of the agrarian problem in Russia as compared with Western Europe, but also the difference between Lenin as a revolutionary leader, and the most prominent representatives of European scientific socialism. Lenin studied the agrarian problem not only from the standpoint of interpretation of the development of capitalist fortunes, and the correctness or incorrectness of Marxian economic teaching in the field of agriculture, but above all from the standpoint of the struggle of the proletariat for power, from the standpoint of selecting for the proletariat an ally in its struggle.

Kautsky could find this ally only in the agricultural worker. But how far this refusal to attempt the conquest of the poverty-stricken peasant on the basis of mere opportunism was the result of either good or bad application of Marxism, or even the result of the passiveness of the German Social Democrats, their absolute refusal to struggle for power, and the tendency of the German proletariat to- ward the co-operative interests-is best illustrated by the fact that the German social democrats were unable even to begin the struggle for the winning of the agricultural laborers, the element in the village which Kautsky had considered the ally of the proletariat. In Russian economy Lenin found in the peasantry the ally of the proletariat in its struggle for power, and for decades taught and advocated the formation of an alliance between the struggling proletariat and the peasantry.

Plekhanov denied the illusions of the Populists regarding the peculiar revolutionary role of the peasantry, since he was unable to concentrate the attention of the Russian working class upon the problem of alliance with the peasantry as the class without which the proletariat would be unable to conquer power and against whose will socialism could not be introduced. This Lenin was able to accomplish, and here Lenin, the great independent proletarian thinker, was transformed into a political leader. To direct the struggle of a class presupposes a thorough knowledge of the conditions of its victory, and ability never to forget these conditions either in moments of great triumph or in times of violent defeat. Lenin’s relation to the peasantry marked a new era in the history of the labor movement throughout the world. The agrarian problem will not play the same concrete part everywhere that it did in the Russian revolution. In all the advanced capitalist countries, the workmen will take a more outstanding role than in Russia, but everywhere the problem of conquering the means of producing bread will play the most decisive role in the proletarian revolution. And this role of conquering the means whereby bread is produced, Lenin was the first to point out to the international proletariat both in theory and in practice.

But there is another angle to Lenin’s interpretation of the agrarian problem which appears to be his fundamental contribution to the future struggle of the international proletariat. In their struggle against opportunism, the representatives of revolutionary Marxism of Western Eu- rope “threw out the baby with the bath-water.” Even when they refused to accept Lasalle’s view of the bourgeoisie as “one reactionary mass,” they in reality feared the alliance of the proletariat with non-proletarian elements. Lenin, struggling in the most decisive manner against the Menshevik policy of alliance with the liberal bourgeoisie, as with a class incapable of marching with the proletariat to the overthrow of absolutism, had with unfailing energy raised the problem of union with the peasantry, with the petty-bourgeois class whose interests demanded the overthrow of czarism. He thus taught even the proletariat of other countries to look upon the problem of union with other non-proletarian elements, not from the standpoint of an abstract denial of alliance in general, but from a concrete point of view, from the standpoint of the analysis of the interests of a given class, on the basis of the problem at what interval of the historic course can a non-proletarian class or a part of such class march together with the proletariat against an enemy which must be removed. In his pamphlet “Leftism-an Infantile Malady of Communism,” Lenin advocated as one of the fundamental conditions in the proletarian struggle for the possession of power and for retaining power, the conquest of the mass-ally no matter how weak it might be.

The chief contribution of Lenin, as the statesman who paved the way for the possession of power by the proletariat, was his teaching of the significance of a proletarian party. To understand Lenin’s controversy with the Mensheviks in 1903 regarding the role of the party and the personnel entering into its make-up, is to understand one of the cardinal points of Lenin’s policy. Lenin taught the proletariat the art of manoeuvering in the class struggle. This problem he presented to the proletariat at the beginning of his historic work; but simultaneously he taught that there can be no organized struggle of the proletariat unless it unites into one manoeuvering unit. If his teachings regarding the relation of the proletariat to the peasantry and the liberal bourgeoisie are the teaching of the manoeuvers of the proletarian party, then his views of organization are his teachings of how to preserve the proletariat from becoming a passive object of the enemy’s manoeuvers.

In his controversies regarding the first paragraph of the statute of the Social-Democratic party, Lenin presented a problem not less important than in all his political controversies with the Mensheviks. Moreover, this problem regarding the first paragraph of the statute presupposes the realization of Lenin’s entire political plan. The working class of Russia had lived under the weight of czarism which did not permit it to create a powerful mass organization. The working class proceeded into the struggle against autocracy through economic and political strikes in the most elementary manner. The Mensheviks dreamed of founding a broad mass proletarian party, which would have found no place under the state of Russian czarism. All talk of an all-inclusive democratic organization under such conditions was vain; in reality it opened the ranks and the doors of the labor party to all those who expressed their sympathy with the labor movement and who supported it materially. This meant the subjection of the revolutionary labor movement, not yet consolidated, to the petty- bourgeoisie. Under the state of czarism, which antagonized wide circles of petty-bourgeois intelligentsia of humble European liberalism, every lawyer hid himself under the banner of socialism. Those who admitted him into the labor party merely on the condition of acknowledging its program and supporting it materially, surrendered the growing labor movement into the hands of the petty-bourgeoisie. Lenin, in demanding that only those who work in some illegal proletarian organization should be considered members of the party, was striving to decrease the danger of subjecting the labor movement to the petty-bourgeois intelligentsia. Even he who broke away from bourgeois society and, venturing to belong to the illegal proletarian organization, became a professional revolutionist did not as yet fully manifest that he would remain faithful to the cause of the proletariat, but he at least offered a certain guarantee.

By marking the way for the proletariat on the basis of Marxian analysis, and by creating an illegal organization of professional revolutionists, Lenin paved the way for the centralization of the revolutionary leadership in the proletarian struggle. The better socialists of Europe, even Rosa Luxemburg, who vigilantly followed the struggle of the Russian proletariat, saw in Lenin’s views of organization an expression of conspiratory tactics, and feared the breaking away of the Bolshevik organization from the mass struggle of the proletariat. This fear however was later shown to be unfounded. The Mensheviks created a very broad organization in moments of uprising, but this organization was directed by the feebly opportunistic intelligentsia. Lenin, on the other hand, created an organization which was able to direct the proletarian struggle in its most difficult moments, which could maintain its revolutionary principles in the years of peace and which appeared as a wide mass organization in a period of great historical upheaval, drawing the proletariat into the class struggle. Lenin never adhered to any special doctrine of form of organization; from the illegal organization before 1905 consisting only of thousands, and through the mass organization consisting during the first and second revolutions of tens of thousands of men, he brought the communist party to hundreds of thousands which, after the October revolution, influenced millions of people. The forms changed from time to time, but throughout all these changes of form Lenin carried one idea: for the proletariat to win the victory a revolutionary organization is absolutely essential. This organization must be solidly united and concentrated, for its enemy is ten times as powerful.

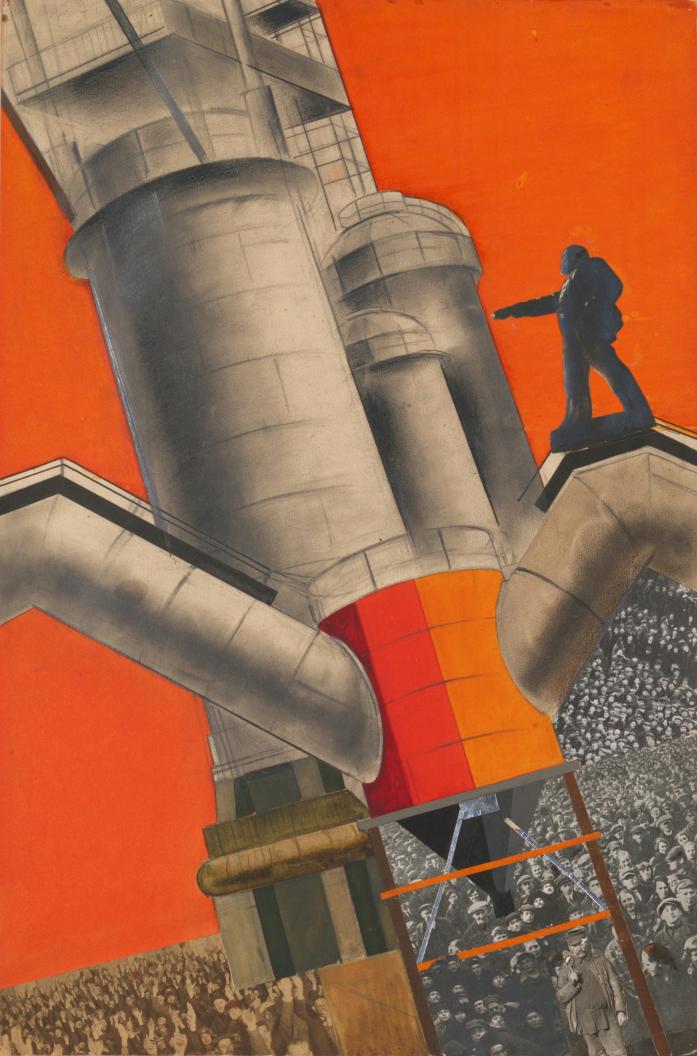

Having formed a mass party capable of manoeuvering in battle against the enemy, Lenin places first on the program the problem of preparing an armed uprising for the possession of power. He was able in the moments of our weakness, or when we were thrown back after defeat, to teach his party to struggle for every foot of ground, for every position, to go through the greatest daily hardships, and thus to accumulate power for the proletariat. Not once in his life however did he forget that all this effort had one goal; it was preparation for armed uprising, for seizing of power by the proletariat.

There is nothing more instructive for a contemporary communist than a comparison of Lenin’s work during the time of the victorious counter-revolution with his work during the greatest upheaval of the labor movement. When the first revolution was crushed, he struggled in the most decisive manner against all those who refused to acknowledge the victory of the counter-revolution and who, hoping for a new spontaneous rise of revolutionary forces, refused to undertake the hardship of gathering new forces and to utilize for this purpose all their resources; however, with the same energy he fought against those who lost their revolutionary perspective and were willing to exchange the revolutionary struggle of the proletariat for a struggle for an insignificant reward. At this time of reaction Lenin studied the lessons of 1905 most diligently, in order that he might be able to utilize them in the next uprising.

How valuable in this direction, is his article of 1908, published in the journal of the Polish Social-Democrats, in which he even then, on the basis of the lessons of the Moscow uprising, raised the problem of technical preparedness for the next armed rebellion.

During the imperialistic war, when the labor movement of the entire world was broken up not only by the military apparatus of the bourgeoisie, but also by the treachery of the Social-Democrats, Lenin, while aiding every practical move of his adherents and occupying himself with every definite means of creating an illegal organization by utilizing all legal possibilities, simultaneously developed, during his exile in Switzerland, Marx’s teachings concerning government and the dictatorship of the proletariat; and thus he prepared for the uprising of October, 1917. Even people like Mehring and Rosa Luxemburg, who never for a moment laid down their arms before the victorious German imperialism and the triumphant social-patriotism of the International, nevertheless considered the fact that Lenin advocated civil war in his first manifesto to the Bolshevik central committee issued two months after the opening of the world war, nothing but romantic sentiment. They did not even at this moment dare to advocate the split of the German social-democracy.

Lenin had at this dark hour already begun to prepare for the October proletarian uprising. But the same man, having returned to Russia during the first weeks of the February revolution, presented to his astonished comrades the idea of the soviet power, simultaneously with unheard- of patience taught the party to interpret the situation to the masses still living in the social-patriotic maelstrom and, to move step by step in accordance with the growth of the revolutionary crisis among the masses. Lenin, who came to Russia with the idea of the soviet republic in mind, advocated the idea of a constitutional assembly as a stage preceding the soviet republic. The idea of a soviet republic was then his guiding star, but he understood that the masses would follow this star only after being disappointed with and dissuaded from the idea of democracy and the constitutional assembly. He did not demand that they skip the democratic stage; he himself wanted to live through this stage with them; he abandoned this idea only after the conquest of power, when the constitutional assembly had demonstrated to the public that it was an obstacle in the way of peace, for which they had struggled in the first place.

Marxism as a whole taught the proletariat how to fight for power. But this idea was concealed from the international proletariat, not only because of the opportunism of the social-democrats, who exchanged the dictatorship of the proletariat for bourgeois democracy, but because after 1871 the European labor movement developed on the basis of bourgeois democracy in all its details. Lenin opened anew the teachings of Marx regarding the dictatorship of the proletariat, not only because he was the revolutionary disciple of Marx, but also because the Russian proletariat was entering the struggle for power.

Lenin, as the leader of the October uprising, and Lenin, as the director of the soviet power, appears as the highest expression of all his teachings during the period of preparedness. “A revolutionary statesman must consider millions of people,” Lenin would say. And he, as the leader of the soviet power taught the world proletariat in the millions what a small group of Bolsheviks had taught them during the preceding decades. By the symbol of the scythe and hammer he reminded the entire European proletariat: “Seek your ally among the peasants, for this alliance will give you bread for the revolution; the Red Star of the Red Army signifies that the power of the enemy must be broken by the power of the proletariat, who leads behind him those classes of society whose interests demand a struggle against the landlord and capitalist reaction.” Standing at the head of a tremendous government machine, he proved to the proletariat of the entire world that power can be retained only by the support of the consolidated advance guard of the proletariat, the communist party. Thus Lenin tested his theoretic teachings in practice, and by means of this test became the teacher of the international proletariat and the founder of the Communist International.

Lenin as the Founder of the Communist International

EVEN during the period of his first sojourn in western Europe, prior to his exile, Lenin began to study with great interest the labor movements of western Europe which he had formerly known merely through books and periodicals and which he was now able to study in actual practice. He often told of the impression made on him by the Swiss and French workers’ meetings; how his new observations contradicted the pictures which he had created in his own imagination, while in Russia, regarding the European labor movement. But the great realist did not for one moment surrender himself to skepticism, but sought the revolutionary essence of the West-European labor movement in its daily tasks. Lenin did not come into close contact with the labor movement and its leaders in Germany, Switzerland, France and England until 1901, when upon his return from exile he took part with Martov, Axelrod and Plekhanov in the publication of the “Iskra.” The “Iskra” became the fighting organ not only of the Russian Social-Democracy but of international socialism. The time of its publication coincided with the climax of the conflict between the revolutionary and revisionist tendencies of international socialism. The practical problems of the West-European labor movement were analyzed in the “Iskra,” for the most part by Plekhanov. Lenin directed his attention mainly to the theoretical side of this problem, but at the same time studied carefully the development of the labor movement. He visited workers’ meetings in Munich, listened attentively not only to the speeches of socialist orators at meetings in Hyde Park, London, but also to the speeches of the advocates of various religious sects, which found a lively response among the working masses of England.

It became quite clear to Lenin, from the first active appearance of Bernstein, that revisionism represented the expression of the interests of the labor aristocracy and labor bureaucracy. This Lenin now saw demonstrated through the different types in the labor movement. At the International congresses at Amsterdam and Stuttgart he observed the leading organizations of the Second International and undoubtedly felt himself quite alone. The debates at the Stuttgart Congress on colonial policy, and on the struggle against the danger of war, showed Lenin the road pursued by the leaders of reformism. The articles which he wrote on the sessions of the International Bureau after the first revolution, were already saturated with profound hatred for all these Van Kal’s, Traelstras and Brantings.

At that time the International itself was not yet broken up, but Lenin was aware that it contained enemies of the working class, and the entire worthy company of the Second International, from the open revisionists down to Kautsky whom Lenin had met in 1901 in Munich, and in whom at best he recognized a man with his head in the clouds. The theoretician of Polish Marxism, Comrade Warski, pointed out very cleverly in his article on the lessons of the Bolshevik anniversary, that while the entire left wing of the Second International, including its better men, represented the opposition to reformism in the Second International, it was Lenin alone who became the initiator of the Third. Suffice it to read in “Enlightenment” Lenin’s short review of a book written by the German Trade Union leader, Karl Legien, about his visit to America, to recognize that on one except Lenin wrote about this honorable company in this manner.

The disagreements between revisionism and radical Marxism, at that time headed by Karl Kautsky, were merely differences in the interpretation of Marxian doctrine. In reality, in daily practice, these two tendencies agreed pretty well with one another, and upon this fact rested the unity of the Second International. The congress met for some years without giving rise to any serious conflicts. Usually their work resulted in the acceptance of some common resolution. In actual practice the so-called radical Marxists did not even propose a revolutionary preparedness of the masses by means of clear and decided revolutionary agitation. In 1910 in Germany a split in the ranks of the so-called orthodox Marxists was noticed. It was a split on practical grounds, on grounds of action. The so-called left radical section and the so-called center, with Kautsky at the head, were formed. The division took place on the questions of the fight against imperialism and of mass strikes. At first it appeared to Lenin, that we, the left radicals, had incorrectly formulated our attitude to imperialism but were absolutely right on the question of a general strike. While Martov’s article against Rosa Luxemburg appeared in Kautsky’s organ, Lenin published in the Russian Central Organ the article of Pannekoek in defence of the position of the left radicals and morally supported the left.

The War Breaks Out.

The dark day of August 4th came. Lenin, exiled in the Carpathian mountains, received the news of the complete treachery of the German and International Social-Democracy. For a moment he doubted the news, thinking it perhaps a trick of the international bourgeoisie, as a war manoeuvre; but soon he was convinced of the tragic reality and, having left Austria for Switzerland, immediately took up his fighting position. I had an opportunity to talk to Lenin as early as the end of 1914, when his position had already been expressed in the historical manifesto of the Central Committee of the Party and in a few numbers of the “Social Democrat.” I shall always remember the profound impression my conversation with Lenin made on me. I had come from Germany to establish communications with revolutionary groups of other countries. In Germany we unconditionally rejected the position of the Social-Democratic majority from the first day of the war. We rejected the defence of the Fatherland in an imperialistic war. We clashed in the struggle with Kautsky and Haase, who did not go beyond the confines of timid opposition to social patriotic leadership in the party and differed from this only in that they yearned for peace. In our propaganda conducted in the censored press as well as in the hekto-graphed leaflets, we advanced the prospect of revolutionary war against war. But my conversations with Lenin meant to me, and through me to my German comrades, an abrupt move to the left. The first problem Lenin put to me was the prospect of a split in the German Social-Democracy. This question was like a dagger in my heart and in the hearts of my comrades. We had spoken thousands of times of reformism as a policy of the labor aristocracy, but in spite of it cherished the hope that after the first patriotic outbreak the entire German party would turn to the left. The fact that Karl Liebknecht did not vote openly against war on August 4, may be explained thus: that he had hoped that under government persecution, the entire party would break away from the government and the defence of the imperialistic Fatherland. Lenin put the question directly; what is the actual policy of the Second International? Is it an error, or a betrayal of the interests of the working class? I began to explain to him that we stood at the parting roads of two epochs: the epoch of the peaceful development of socialism within the limits of democracy, and the epoch of storm and stress, that it was not merely a question of the disloyalty of the leader but of the attitude of the masses, who unable to find sufficient force to oppose war subordinated themselves to the policy of the bourgeoisie; and that the hardships arising because of this policy would force the masses to break away from the bourgeoisie and to enter upon the path of revolutionary war. `Lenin interrupted me by saying: “It is an historicism that all of this is explained by the change of epochs; but can the leaders of reformism, who had even before the war systematically led the proletariat into the camp of the bourgeoisie, and who at the outbreak of war went over to this camp openly, can they now become the champions of a revolutionary policy?” I answered that I did not believe it possible. “Then,” declared Lenin: “the reformist leaders, survivors of an outgrown epoch, must be cast aside. If we actually wish to facilitate the transition of the working class to the policy of war against war and war against reformism, we must break with the reformist leaders and with all who are not honestly fighting against them. Now the problem of when to break off, how properly to organize and prepare for this split, is a problem of tactics, but to strive toward this break is the fundamental duty of every proletarian revolutionist.” Lenin insisted upon the keenest form of ideological war against the social patriots; he insisted upon the absolute necessity of an open declaration of the treachery committed, especially the treachery of these leaders. He repeated these words many times when we worked together later; when drawing up resolutions he always attacked on the basis of this political definition, considering it the index of revolutionary sincerity and logic, and of the will to break away from the Social-Democracy.

With the same sharpness Lenin presented the problem of opposing the Slogan of Civil Peace with the Slogan of Civil War. Since the time of our polemics with Kautsky, we German left radicals had become accustomed to advance the less clearly-formulated slogan: “mass action.” The indefiniteness of this slogan corresponded to the embryonic state of the revolutionary movement in Germany in 1911-1912, when we regarded the demonstration of the Berlin workers in the Tiergarten at the time of the struggle for universal suffrage in the Russian Diet as the beginning of the revolutionary struggle of the German workers. Lenin pointed out, that although this slogan might be suitable for the purpose of opposing mass actions to the parliamentary combinations of the leaders of the German Social-Democracy in pre-war times, it became absolutely unsuitable in times of blood and iron, in time of war. “If,” he said, “the discontent with the war should increase, even the centrists will be able to organize a mass movement in order to exert pressure upon the government and force it to end the war by a peaceful agreement. If our aim, the aim of exchanging the imperialist war for a revolution is not to become merely a useless wish, but a goal for which we really want to work, the slogan of civil war must be definitely and clearly advanced.” He was greatly pleased when in his letter to the Zimmerwald Conference Liebknecht used the words: “against civil peace-for civil war.” This was proof to Lenin that in essentials Liebknecht was in agreement with us.

The split in the Second International as a means of forming the revolutionary movement of the proletariat, the civil war as a means to victory over imperialist war- these were two fundamental ideals which Lenin had endeavored to impress on the minds of the advanced revolutionary elements in every country with which he had contact. Despite the fact that Lenin had even then insisted definitely and clearly upon the later Communist Inter- national, he nevertheless went to the Zimmerwald and Kienthal conferences called by the anti-war militarist Social-Democratic organizations. He well understood that it was necessary first to awaken the minds of the workers by forming blocs with the centrist tendencies, to shake the unity of Social Democracy, and to gather together considerable sections of the working masses, in order not to be satisfied with propaganda alone, but to begin the actual struggle.

Not only did he follow attentively all the documents produced in the course of the struggle of the various tendencies. This, by the way, he did without sparing any pains. It is sufficient to state that he read the pamphlet of the Dutch Marxist Horter regarding the war from the first page to the last with the help of a dictionary, without knowing a word of the Dutch language. He also followed most attentively every minute symptom of revolutionary self-activity among the masses, endeavoring to ascertain the degree of political development already attained. When in Berne, Switzerland, from an old comrade who since the nineties had stood at the extreme left wing of the German Social-Democracy, but who was absolutely ignorant on questions of principle, Lenin obtained literally a complete picture of the movement. I remember the astonishment of this Social-Democrat, when Lenin gave him no rest, until he had told him what the working men and women shouted at the demonstrations. “They shouted the usual things!” the Social-Democrat replied. But Lenin insisted: “Still, you must tell me, just what did they shout?”-until he obtained from the man the necessary information. He followed with the greatest attention all details in the European and American press in order to discover the trend of feeling of the masses, which the political articles, strictly reviewed by the war censors, no longer expressed. The great revolutionary leader sought even in foreign countries this intimate relation with the working masses which alone made it possible to find the keynote of the movement. He spent whole evenings in saloons in order to discern the real foundation of the movement, in talk with the Swiss workers, who were by no means the best products of revolutionary thought. When the comrades at that time leading the left wing of the Swiss labor movement were shaky and hesitant, he insisted that every one of us seek contact with at least small groups of the workers, upon whom alone he relied.

As early as 1916 when we had gathered small groups of adherents in different countries, and in the ranks of the Zimmerwald bloc had created the so-called Zimmerwald Left, Vladimir Ilyich insisted that we begin drawing up the program of the future revolutionary International.

Out of this preliminary work of his, his book “The State and Revolution” appeared later. As early as 1916 he advocated the idea of the State-Commune, which at first was no more intelligible to us than the famous April thesis of Lenin was to our Russian comrades. All of us had read Marx’s book about the Paris Commune many times, but we had overlooked the new idea it contained, the idea of the State-Commune, and Lenin had with great difficulty made clear to us his own point of view. It was very characteristic of him as a tactician that the experience of 1905 had even then caused him to point out to us the possible role of the Soviets as the organs of the State-Commune. But at the time of the February revolution, Lenin having only vague information regarding the actual situation in Russia, in reply to a question of comrades Pyatakov and Kollontay, departing for Russia and asking for directions, he said: “No confidence in the provisional government. The constitutional assembly is nonsense. The Petrograd and Moscow Dumas must be taken possession of.” In the struggle for the State-Commune, Lenin sought the aid of organs closely related to the daily life of the masses, without concerning himself greatly as to the names of the organs.

One of the results of his program work of this period is his attitude toward the question of self-determination of peoples. Before the war Lenin advanced this problem from its Russian aspect, as a means of freeing the Russian proletariat from the influence of Great Russian Chauvinism, and as a means of winning the good will of the masses of non-Russian peoples in Russia, in whom he hoped to find the ally for the struggle against Czarism. During the war he approached this problem on its international aspect. Rosa Luxemburg’s pamphlet on the bankruptcy of the German Social-Democrats, in which she generally disputed the possibility of liberation by means of wars of national emancipation in the period of imperialism, induced Lenin to advance the question of self-determination anew. With unprecedented tactical flexibility, though rejecting decisively the so-called defence of country for imperialistic governments suffering from the West-European narrowness of horizon he pointed out to us, that if the period of national wars has passed in Western Europe, it has not yet passed in Southwestern Europe, it has not passed for the national minorities in Russia, nor in the colonies in Asia. Lenin had not devoted himself to a concrete study of the colonial movements before the war; in these problems many of us knew ten times as much as he, and he strove most conscientiously to collect the necessary concrete mate-rial through books and discussions. But he turned this material against us, and in the question of the self-determination of peoples, combatted the position of Kautsky, for whom this slogan became the weapon of pacifism and a solution of the Alsace Lorraine problem. With the severe criticism he directed against my thesis on the question of self-determination of peoples, he taught us the significance of this problem, as the dynamic force against imperialism. The cunning centrist philosophers, like Hilferding and his ilk strove to prove to the European proletariat that Lenin advanced the colonial and national problems at the second congress of the Communist International in the interest of the government. But Lenin led a bitter war against Gorter, Pannekoek, Bucharin, Pyatakov and myself in this question, while still a persecuted emigre in Switzerland. This question had for him the same significance as the winning over of the peasants on an international scale as an ally for the world proletariat. Without alliance with the revolution of the young enslaved peoples of the East and of the colonies, the victory of the International proletariat was impossible. This Lenin taught us as early as 1916.

From the very beginning of the February Revolution, Lenin strove to destroy the bloc with the centrists for the liquidation of the Zimmerwald Union. He considered that the Russian Revolution, raising the question of revolution in all belligerent countries, would give to us communists a mass force and thrust all the irresolute elements of the centrists into the camp of the traitors. He did not permit us to sign the manifesto of the Zimmerwald Commission regarding the Russian Revolution, for he saw that our signatures along side of Martov’s, might confuse the Russian workers and would interfere with the struggle against Tscheidze and the Mensheviks. This split did not take place during 1917 for we strove to make use of the Zimmerwald Bureau to induce the Independent Socialists in Germany to take up the struggle against German imperial- ism; the Spartacus Union had not yet separated from the Independents. After the seizure of power in October, 1917 the Zimmerwald Union practically died. The struggle of the Russian working class proved to be the chief means of awakening the world proletariat. The whole year of 1918 was devoted to the preparation of the constitutional congress of the Communist International.

This congress, which took place in 1919, at the moment of the opening of the struggle with Denikin and Kolchak, created nothing new in principle. It was based upon the ideological activity of the Bolsheviks in the Zimmerwald Left, in the preceding years of the War. Its decision, the Manifesto, and above all Lenin’s thesis on dictatorship and democracy, laid the foundation for the future work of the Communist International. At the time of the October Revolution, many reading the decrees on peace and on the land, thought that these documents would share the fate of proclamations which are never executed. In the most critical moments of the Russian Revolution, when the news was received of Kolchak’s movements to- wards the Volga and of the defeat of the young Red Army in the South, the decisions of the first Communist International were issued; and not only many of the West-European Communists but also many of us, members of the Russian Communist Party, working illegally in the West asked ourselves whether these documents were not the legacy of the Russian Revolution which was in deadly danger. The executive of the Communist International, cut off by the blockade from the West-European Labor movement, could have very little practical influence on its movements, could give very little aid to the West-European workers. They independently paved the way for them- selves, learned to solve their own problems, and not until 1920, with the victory of the Red Army over Denikin and Kolchak, did the daily activities of the Russian Communist International begin. And now Lenin rose at the head of the International labor movement, as its practical leader, as its good genius, helping the young Communist movement to understand its first steps and to find its future way.

Lenin wrote three important documents for the second congress of the Communist International. Delegates coming from all over the world found translations of Lenin’s pamphlet “Leftism-The Infantile Disorder of Communism.” They were acquainted with Lenin’s “The State and Revolution,” like a torch lighting the way to their great goal-the dictatorship of the Proletariat. His pamphlet on Leftism lighted the way of the young communist parties which had thought that in one leap they could seize the enemy by the throat, that the revolutionary wave would bring them straight to their goal. Lenin taught the young communist parties, refusing any compromise in the revolutionary strife, to consider the experience of the Russian Revolution. He pointed out to them that in order to attain the dictatorship of the proletariat it was first necessary to win over the majority of the working class. He pointed out that in order to win over the majority of the working class every means supplied to the more advanced workers by the very bourgeois democracy which they intended to overthrow, must be utilized. He pointed out to them that if the way to the barricades should lead through the Parliament, the idea of Communism must be preached to the working masses from even this dunghill. He pointed to the mass organization of the proletariat, to the trade unions which must be snatched out of the hands of the yellow leaders by unwearying efforts. He pointed out that the revolutionary minority cannot decline to compromise, if this compromise might facilitate the winning over of the majority. It is difficult to cover in a few words the contents of this memorable work of the great leader. We must say that nine-tenths of the leaders of the Communist International have not even yet fully mastered this pamphlet. This little pamphlet contains the quintessence of the entire philosophy of bolshevism, its strategy and tactics, and many years of victory and defeat will pass before we shall be able to say that these ideas of Lenin have really become part of the flesh and blood of the leaders of the Communist International. The more one reads this pamphlet, the more new ideas and finer shades of thought one finds. Suffice it to say that after two years of application of the united front tactics, only last year did I discover that this had been already developed in the pamphlet, though I had completely forgotten this when for the first time I applied these tactics in 1921 to the famous “Open Letter” to the Social-Democratic parties and the trade unions. The inexhaustible lessons either developed in or contained between the lines of this treatise about the class-war will have for our strategy no less value than Clausevitz’s book “Of War” had for military strategy. The difficulty of applying these lessons is the impossibility of learning the strategy of the proletariat by means of propaganda, by discussions on the struggle of the Russian proletariat. The daily experience of the Communist parties the world over constantly changes the form in which the fundamental problems arise, and the independent activity of mind of every Communist party is essential if it is to rise to the level of revolutionary strategy of our greatest revolutionary leader.

The second document offered by Lenin at the second Congress, was his first draft of conditions of admission to the Communist International. These theses have been ridiculed, many protests were levelled against them; but when we read them, when we inquire which of these parties comprising the Communist International has already learned to fulfill even one tenth part of these conditions, we see their great political significance. If Lenin’s book “The State and Revolution” showed us the goal of the Communist movement or, speaking more precisely, its first great stage of the journey; if this pamphlet on leftism shows the whole difficult path of the struggle for dictatorship-these theses of Lenin present the problem of what the Communist party should become. It does not pay to pass any new resolutions without first verifying how far these theses have been fulfilled. These theses are a test, a measuring rod of the degree of development of the Communist International from the social democratic left parties into real Communist parties.

The third of Lenin’s documents was his draft of the theses on the colonial question. Even these have not yet permeated the flesh and blood of either the proletarian Communist parties of the West, whose hundreds of millions the bourgeoisie still holds in its savage claws, nor the minds of our young Communist parties of the East. The work of the English, French and Dutch comrades in the colonies is met by the most tremendous difficulties not only through the police of the imperialist governments, but also by the lack of preparation of our comrades for work among colonial masses of an unbelievably low cultural level. Our comrades in the colonies very often err on the side of left Communism. Raised on the literature advocating the struggle for the dictatorship of the proletariat, they are learning with great difficulty to associate the struggle for the unification of the young proletariat and the artisans of China, Corea, Persia, India and Egypt against the foreign and the native bourgeoisie, with the attempt to support the national emancipation movement of the young native bourgeoisie against the foreign capitalist bourgeoisie oppressing them. Decades will pass before it will be possible in practice to combine the national liberating struggle of the colonial peoples with the proletarian revolution in Europe and America. But one thing is now clear: Lenin’s genius has shown the way to the international proletariat. In the person and teachings of Lenin a unifying center for the struggling masses of the world was created for the first time in the history of the class struggle. For the first time we are beginning to find our way out of the impasse in which the European proletariat had remained, and to find the path of a real world movement. The book of our Hindu comrade Roy about India gave us the first test of Lenin’s teaching in a concrete example. The struggle carried on by the newspaper edited by Roy gives the first test of the periodical application of Lenin’s teachings, and we say, that this test proves how far and how keenly our leader could see. the time of the Hamburg Congress of the Second International, the Hamburg social democratic newspapers printed a poem of welcome to the Congress. The poet appealed to the Chinese Coolie working in the rice fields, to the Negro toiling in the cotton fields of America, to the Negroes mining for gold, and called them under the liberating banner of the International. But these were vain words. This same Second International is now celebrating a great victory. Its leader, Ramsay MacDonald organized the first labor government. But whom did he appoint to the ministry over the affairs of three hundred million op- pressed Hindus? Sir Sidney Olivier, an official of the old colonial office, the Governor of Jamaica. This colonial official is an experienced defender of the interests of the owners of the sugar plantations in Jamaica. Will he now call the Hindu workers of his majesty, the King of Eng- land, under the banner of the Second International or will this perhaps be done by Lord Chelmsford, formerly the Viceroy of India, who was appointed the first Lord of the Admiralty by the grace of Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Second International? Only the Communist International can organize the colonial workers, and the merit of Lenin, in showing us this road, will remain memorable in history to the international working class and to humanity.

The third congress of the Communist International saw Lenin still at his battle post. The wave of revolution of 1918-19 had disappeared. The German communist party, having become the mass party of the proletariat, marking neither the change of the situation nor that the attack of capital had already begun, permitted itself to be deceived, and rushed armed into battle with not even the sympathy of the majority of the toiling masses behind them. We all understood the party’s error, we all rejected the theses of the German Central Committee, which developed the theory of attack at the moment of political retreat. But we, the immediate workers of the Communist International, knowing that the Party Central formed of the old leaders of the Spartacan movement and the best leaders of the former Independent party, was the only possible center of the German Communist movement, wished to teach our German brother party the lessons resulting from their defeat as kindly as possible. forced us to change our theses five times; he forced us to say brutally to the German Communists and the Communists the world over: “First win over the majority of the proletariat, and only then may you face the task of seizing power.” Lenin saved the Communist party, and with the same determination supported the united front tactics which met violent resistance within the ranks of the Communists and not only the ranks of the West-European Communists. With extraordinary sensitiveness he pointed out the fundamental differences between the conditions in Russia in 1917, and the conditions under which the West-European Communists had to fight. He well understood that in dealing with proletarian mass organizations that had accumulated through a period of fifty years, and con- trolled by the yellow leaders, very complicated and very persevering work was essential. A series of compromises is necessary, very difficult for communists, but unfortunately essential for winning over the majority of the proletariat. Overburdened with government work, having no time to follow up the details of the developments in the west, Lenin possessed some peculiar sense which enabled him to grasp the essential differences in the situation of every country, and the problems of every Communist Party.

At the fourth Congress of the Communist International, having just recovered from the first attack of his illness which took him away from us, Lenin reported the situation in Russia. The Congress received him with the deepest joy, and with great sorrow saw the difficulty with which their beloved leader chose his words in order to express his clear ideas in a foreign language. Before delivering his report, Lenin, with a wink inquired; “But what shall I say when asked of the immediate prospects of the world- Revolution?” and immediately answered himself; “I shall tell them that when the communists behave more sensibly the prospects will improve.” Lenin gave directions the method of war against war to the Russian trade union delegates departing for the Hague Conference of the Trade Unions. This last advice of Lenin to the international proletariat represents a sample of his extraordinary realism. He announced that those who promise in spite of the lessons of the imperialist war, to bring about a general strike in case of a new outbreak are either fools or deceivers. If we can not prevent the imperialist war, the masses will be drawn into the war and we too will have to go to war and work for the revolution in the ranks of the imperialist armies. The task is to prevent, with every possible effort, an outbreak of war. And Lenin developed anew, point by point, the plan of daily revolutionary work against the danger of war.

A year of work in the Communist International has passed without Lenin. This year brought us two great defeats; in Bulgaria and in Germany. We must learn the lessons of these defeats alone, without Lenin. The revolutionary wave has not risen as yet, as we expected in the summer of this year. And if it does not rise next year, we shall have to analyze a whole series of complicated problems. We shall have to organize the masses during the period of reaction and the offensive of capital and combine their daily struggle with the preparation for the future struggle for dictatorship. We have forty-two parties- Every one of these exists under different circumstances. It is extraordinarily difficult to consider all the peculiarities of these conditions and despite the differences to carry on united Communist work. But we possess Lenin’s legacy, an inexhaustible source of his thoughts and his methods, tested in thousands of attacks and retreats. We shall learn from Lenin’s works. Just as in Marx it is not the results, not the concrete solutions that are most valuable, but the method of solution, the approach of the greatest of proletarian revolutionaries to the problems.

The Communist International and the Russian proletariat has suffered the greatest loss. If ever the words were true that death takes away the body only, they certainly are true in the case. Therefore the Communist International will shed no tears over Lenin’s grave, but will undertake with renewed energy the mastery of whatever is immortal in Lenin’s teaching, and with Lenin’s sword in hand will be victorious.

Our beloved comrade is no more; the Communist International will solve its problems with the collective thought of all the Communist parties.

Lenin’s banner and Lenin’s teaching arm the Communist International for the entire epoch still dividing us from the victory of the proletarian world revolution.

PDF of issue 1: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1924/04/v7n04-w72-apr-1924-liberator-hr.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1924/05/v7n05-w73-may-1924-liberator-hr.pdf