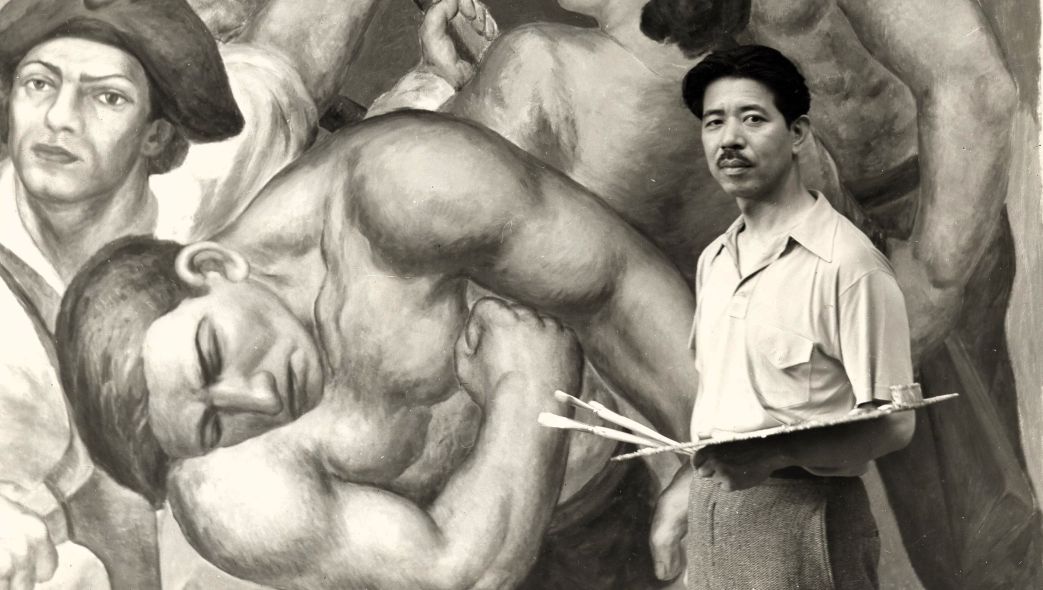

‘Eitaro Ishigaki’s Two Traditions’ by Charmion von Wiegand from New Masses. Vol. 19 No. 5. April 28, 1936.

EITARO ISHIGAKI, born in Japan, has spent the major part of his life in the United States, and has become an American painter working in the traditions of the West. At the same time, he is a revolutionary painter. This conjunction of forces brings sharply to the fore the relation of the revolutionary painter to his native racial tradition. Ishigaki has solved this problem in his own way. In many respects it is the reverse solution chosen by William Gropper in his painting. Yet both are revolutionary artists; they belong to the same generation; they were born between two centuries; they experienced the World War during the formative period of adolescence. Nevertheless, they approach their problems from opposite directions. They have had, however, two major experiences in common- becoming American and becoming revolutionary.

Ishigaki’s rebellion against the bourgeois social order has taken the form of repudiating his native racial tradition. He has sought to take root in the western tradition of art. Gropper has signified his rebellion by repudiating that tradition and finding inspiration in the forms and feeling of eastern art; Gropper works in the very tradition against which Ishigaki rebels.

Each artist in his own way has dramatized the first forms of rebellion-against one’s family, one’s nation, one’s culture. This is the initial revolt of every individual in bourgeois society, who seeks to grow and develop. From this adolescent revolt against the parents, the individual seeks to find his Critical evaluation of way to maturity. one’s own social background is the first move of the artist toward revolutionary activity.

Ishigaki is the son of a worker, hence he never was deeply affected by the culture of the Japanese ruling classes. His father, a boat builder, emigrated to the United States when Ishigaki was sixteen years old. Despite the cruel fact of racial discrimination, a superior technical civilization and a democratic tradition provide the worker with more benefits than a half-feudal society. Hence the youth Ishigaki sought to become an American in habit, thought and art. Doubtless in the beginning he shared the faith in democratic shibboleths.

But why had his repudiated cultural tradition nothing to offer him, when it had so happily fertilized nineteenth century French painting? (Manet, Gauguin, Van Gogh.) A study of the Japanese prints of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries now on exhibition at the N.Y. Public Library provides an answer; they represent the popular art of wood block prints in color, made and sold by the thousands in Japan. They were probably the first art which Ishigaki came in contact with and they demonstrate how an aristocratic tradition of sufficient vigor finally permeates down into the masses of the people and shapes their tastes. Most representative, perhaps, of this popular art are the prints of Utamaro, whose favorite subject was the geisha. The impulse that beats through his fragile and perishable prints stamped with gold and scarlet, grey and smoke green, is erotic. They reveal a rococo art of great refinement and sensitivity-rich in subtle color nuances, composed in line of precise and perfect definition. Beautiful as this art is, to a poor worker’s son, it could offer nothing except a tantalizing vision of a paradise never intended for his enjoyment. The young artist who experiences the full impact of the class struggle must find such a static paradise cloying and repugnant, just because it lulls to an opium dream, awakening from which makes reality doubly painful. Hence Ishigaki had to seek his models elsewhere.

Marxism, as well as democracy, grew out of the western tradition. Both are built on the western culture of action whose central core is the deed, whose symbol in art is the human body in three dimensions. Such a pictorial tradition must have been eagerly absorbed by a youth interested in the class struggle and desirous of repudiating the actionless Nirvana of feudal eastern culture, which offers no method for the worker to extricate himself from a serf-like position.

Ishigaki took up the western tradition at a point where the first proletarian art developed-the romantic revolutionary period of 1848. His main theme in all pictures is the world-wide contemporary class struggle. He paints it in the romantic style of Delacroix, thus grafting new subject matter onto the typical western tradition derived from the Renaissance and the classic art.

Yet while Ishigaki has worked in the most characteristic vein of western painting, his work preserves some traces of eastern art-in the manner in which he paints the eyes, and in his preference for circular pat- terns of composition. This circular motif is best realized in the landscape called “Uprising” with a white inspector on horseback between advancing imperialist troops and native workers. Here the brilliant color and the converging figures in motion are reinforced by circular rhythms in earth and sky, giving a sense of a wider cosmic movement.

Ishigaki’s present style is the result of several different phases of development. In the small canvas “Traffic Problem” he offers the comic motif of a fat lady mounting a bus done in the manner of the Japanese print-using his own tradition for satire. much as Quirt does when he makes Renaissance motifs into symbols of derision. Ishigaki has also made his experiments in cubism. “The Whip” uses the motif of horse and rider with the whip in an abstract form; here the horse’s flank and the curve of the lash complete an S composition of terrific intensity. In its sombre greys and browns, “The Whip” combines Cubist form with expressionist feeling; in this it reflects the clash of modern life-the contradiction in terms of class struggle and the tumbling towers of the background suggest the industrial milieu out of which this fight emerges.

Much of Ishigaki’s recent work has a mural quality and he has a predilection for over-life sized forms-for example his massive portrait of an ARM holding a hammer. He is now at work on a mural for the Harlem Courthouse-sponsored by the Federal Art Project of the W.P.A.-and it will be interesting to see how his large forms appear on an actual wall. In choosing for his mural the liberation of the slaves by the Civil War, Ishigaki has found a sympathetic theme. Discrimination against the Negro in the U.S.A. has affected him deeply and such pictures as “South USA” and “Lynching” are among his most dramatic and moving works. Uncompromisingly sincere, Ishigaki is a painter who will not stand still and the course of his further development is of vital interest for revolutionary art.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1936/v19n05-apr-28-1936-NM.pdf