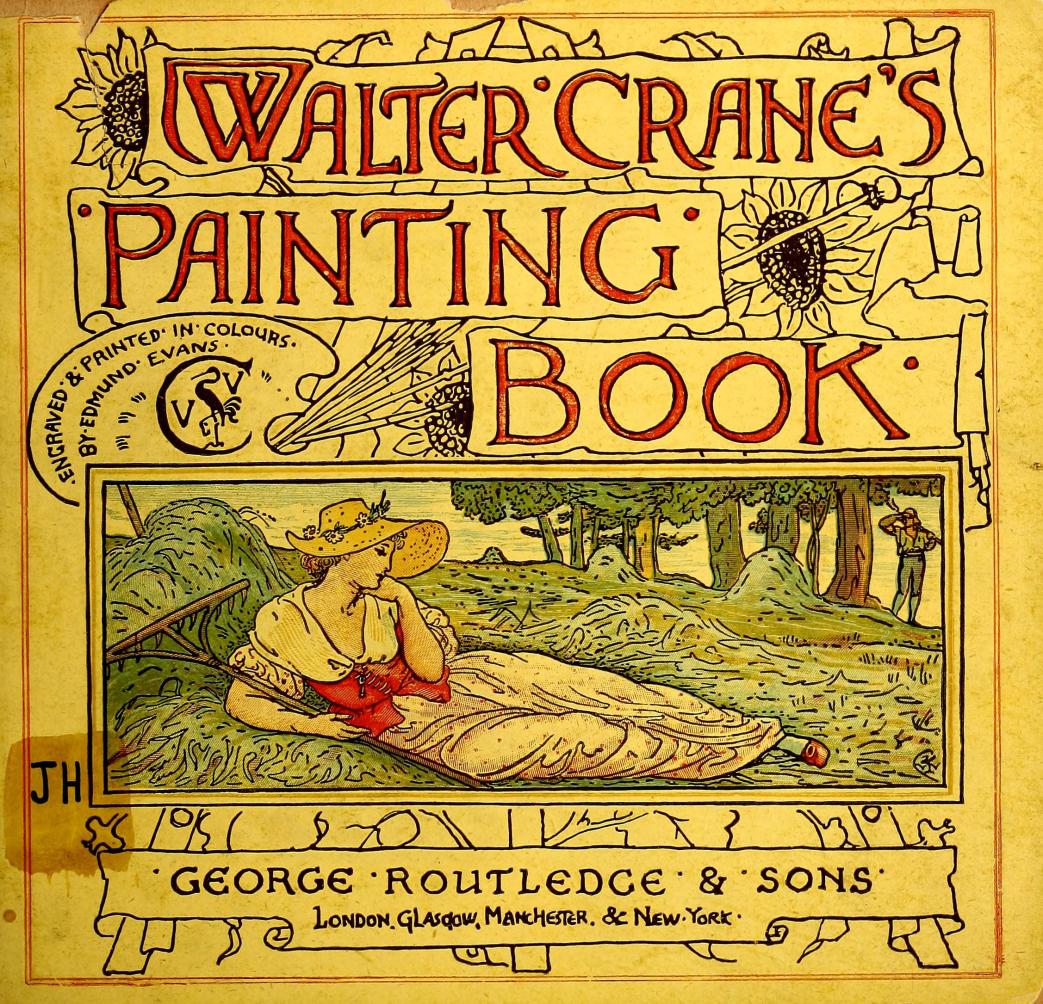

‘The Banner of Art’ by Walter Crane from St. Louis Labor. No. 490. June 25, 1910.

What Is Art.

It is the expression of the joy of life-the passion for beauty- the crown of all human handiwork. It may exist for the delight of a child, or it may perpetuate in immortal form the noblest ideals of a people.

Yet art, being a social product, is subject to the influence of all sorts of conditions, which constantly modify the character of its manifestations, and stamp them with the image and superscription of the age which gives them birth.

Thus, in our time there is much to hinder and distort that spontaneous expression which is of the true essence of art.

The same economic conditions which have enslaved and degraded labor have enslaved and degraded art. The artist is mostly dependent upon a leisure class who live upon surplus values, upon rent, profit and interest derived from the continuous labors of the community or from speculations all over the world. The work of the painter is regarded as a luxury, or as a subject for speculative investment and the chaffering of dealers. True, we have our national and public galleries, where the works of great masters of the past or present may be seen and enjoyed by all- all, that is to say, who have leisure to go to such places. The mass is too much involved in the continuous struggle for the very means of subsistence for the thought of such pleasures. Art is outside their lives altogether.

We cannot be said now to have an art of the people at all. Such art as we have is produced for them, or for some of them, not by them. Modern art is the result of artificial cultivation. Its forms are often highly eclectic and exotic, and to get back to perfect simplicity and what is called “good taste” in the environment of our lives-in our decoration and furniture, our houses and gardens- requires the most careful training, and thought, and long study: and even then is no of much use unless there is already a predisposition in the mind-a sort of instinct for beauty.

The Instinct for Beauty.

It sems strange that this invaluable instinct should ever have been lost. We look back in admiration and wonder at the life of past ages and civilizations long passed away-to Greece, or to the middle ages, or even to China and Japan, before the invasion of Western modes and manners-and we find art intimate and inseparable from the every-day life of the people, as much a necessity as daily bread, and we do not see a single ugly thing.

To judge from the pictures of life in illuminated mediaeval MSS., England was once not only “merrie” but beautiful-her people well and picturesquely clad; her towns rich with lovely architecture-life a perpetual pageant. The fair green country and flower-starred meadows smiling through the gates and beyond the white walls of London. But centuries of industry and commerce, driven by the whips of competition-the scorpions rather-and the desire for riches regardless of by what means they are obtained, have done their work here as elsewhere. The giants, coal and iron, who ought to have been the servants, not the masters of the people, have laid waste the land and leave their blackened footsteps everywhere. In the grip of private ownership, and driven by the goad of profit, coal and iron, like other useful products of the earth, having become necessities, and, it being possible to exploit people through their necessities, they carry curses hopelessly mixed with their blessings wherever they go.

Amid the roar of looms and the throb of machinery, amid the steam and smoke of factories, how can the voice of art be heard? What influence can its ideals have upon the enormous output of goods made up for sale in the great world market? Modern commercial capitalistic commerce pours its torrent of machine-made goods into any opening in that market, until checked by what is called “over-production.”

Art In Fetters.

Well, the trade designer cudgels his brains, or looks up some past fashion, to make the goods attractive. Day in and day out the workers toil in the factory, each blindly doing his or her bit. Great trouble is taken by manufacturers to catch the eye and certainly the penny-of the public, but in all manufactures where color and pattern play a part it is, after all, but guess work. The art, or rather craft, of it is speculative. It is produced just for a season’s goods, on the principle that it may please-well, the average. It is produced not because it is useful or serviceable to mankind, but it is produced for profit. It is the great (unprincipled) principle of modern production.

The principle of artistic production apart from the commercial influence, is quite different. There is the impulse to produce, but to produce a thing that shall be useful or beautiful-that shall be both -the artist, a craftsman, gives of his best, something that gives pleasure in the making, though it may cost both time and trouble, and therefore is sure to give pleasure in the using. There is, too, the principle of working for a definite purpose and, it may be, a definite person or group, and the personal feeling and relationship always makes an important difference in producing a work.

In the old days of local production, home production and handicraft for home consumption, the goods made were excellent of their kind, though without that pretentiousness and “trade finish” our people have been taught to look for. The curse of adulteration was unknown. No people would want to cheat themselves. It has been the sacrifice of every consideration to doing trade at as big a profit as possible and the pressure of fierce competition that have directly encouraged such anti-social practices.

Now, competition, strange to say, has driven us into the jaws of monopoly, which by means of its weapons, “rings” and “trusts,” bids fair to lay its hands upon every necessity of life, including art, and becomes a more sinister power over humanity than ever was known.

The Pursuit of the Shadow.

And this extraordinary commercial and economic evolution has been going on in the midst of the struggle for political freedom and the advance of democratic institutions!

Like the dog in the fable, the people have dropped their economic substance for the illusory shadow of political power seen in the turbid waters of party politics.

It is part of the “bunkum” of modern politicians to talk of “the free and independent elector,” but how can a man afford to express free opinions when he and his are dependent upon someone else for their daily bread? But until the basis of life is fairly secure, until the housing, feeding and clothing question is settled, until every man and every woman has leisure and has attained a fair standard of comfort and refinement of the artistic sense? Yet human life in the higher sense can only be said to begin when those primitive and fundamental questions have been settled, either for the individual or the mass (for life under any circumstances is barbarous without art). They are frequently solved for the individual, no doubt; but for the mass, how can they be while 2 5to 30 per cent. of our town populations are unable to find sufficient means for their physical sustenance under present conditions?

To talk of art while such things be seems almost like Nero. “fiddling while Rome was burning.” The fair flower of art cannot spring from a poor soil any more than any other flowers. Yet the struggling tree beneath the smoky skies and the grime of a backyard in a modern town will still respond to the touch of Spring, and put forth buds and leaves.

The Winter of Art.

The instinct for beauty, the love of color and form, of harmony, of sweet sounds, of the spirit of romance, of the drama of love and life lie deep down in the human heart; warped and obscured it may be, and clouded by circumstance, or palsied for want of air and exercise, but they only await the touch of Spring-the Spring of hope and the stimulus of new thought to be kindled into fresh life. That Spring and the stimulus will be found in Socialism. If every work of art perished in some great conflagration, the instinct for beauty would still remain, and art spring again in new forms from the soil of human life.

Everywhere may still be found the remains of a traditional art among the people, whether in the form of folk songs and tales and dances, or plays, or in the handicrafts, weaving and embroidery, wood carving, metal work, such as are still produced by the peasants of Sweden, or of Hungary, and which of old were produced among our own people, as our village churches still bear witness.

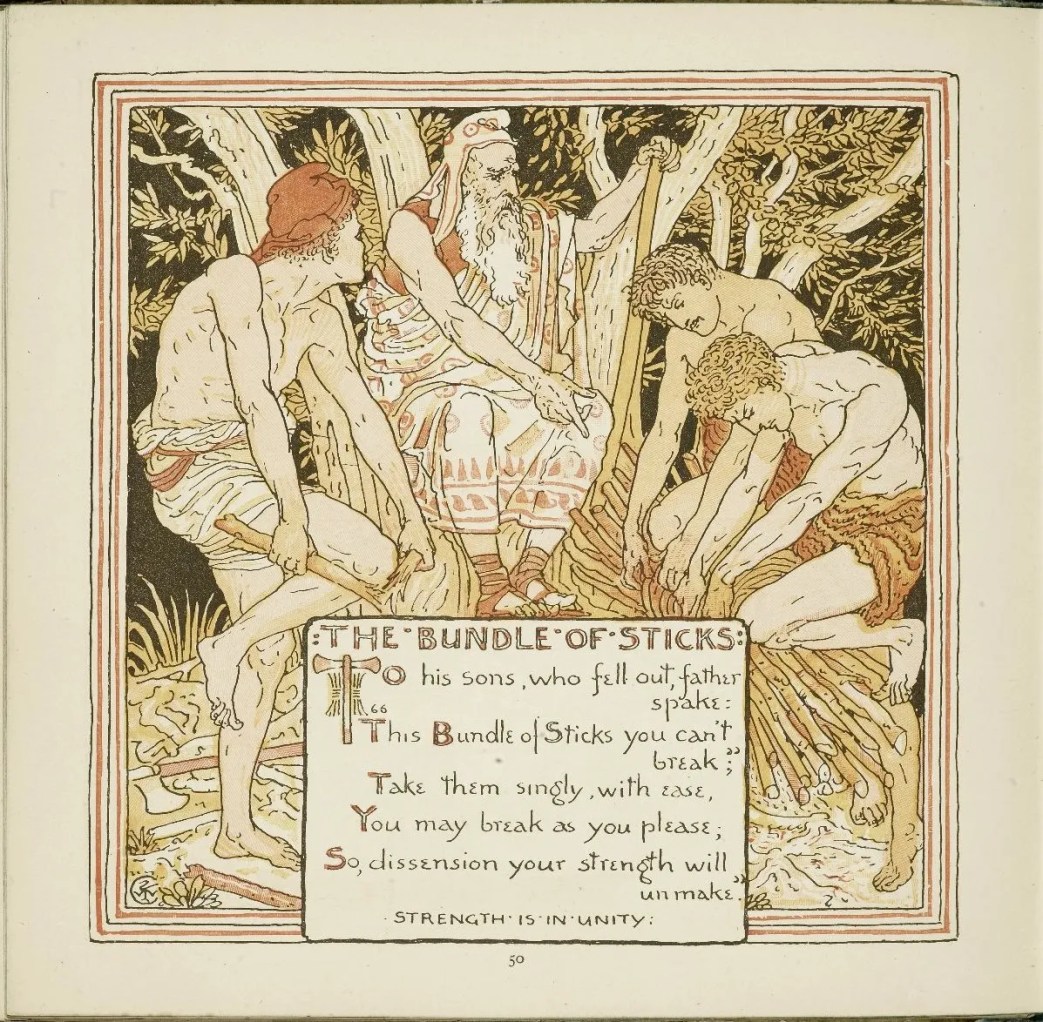

Well, we cannot recall the past, but we may read its lessons. We must face now conditions, new methods. Socialists would be the last to disregard any advantage which modern invention and science has given to us, and the splendid vision of what we might make of the world and of human life which takes shape before us when we contemplate the enormous resources at the command of man, and his increased power over Nature, and his productiveness in every direction should inspire us with the determination to realize the great Socialist ideal. What we protest against is the present waste of effort the wastefulness of the capitalistic system and its artificial starvation amidst plenty. It is alike wasteful of the re- sources of Nature, of art and of human lives. We would substitute co-operation for competition, mutual aid for mutual injury. We would make machinery really “labor saving” by putting upon it the burden of all the heavy toil and monotonous drudgery which now absorb and degrade so many human lives, but we would not set it to turning out millions of futilities of the same pattern for the market, or suffer it to usurp the work only proper and pleasurable to individual brains and hands, or to destroy the beauty of Nature or the joy of art. These things should be the inheritance of all, and play an important part in the thought and life of any people worthy to be called civilized.

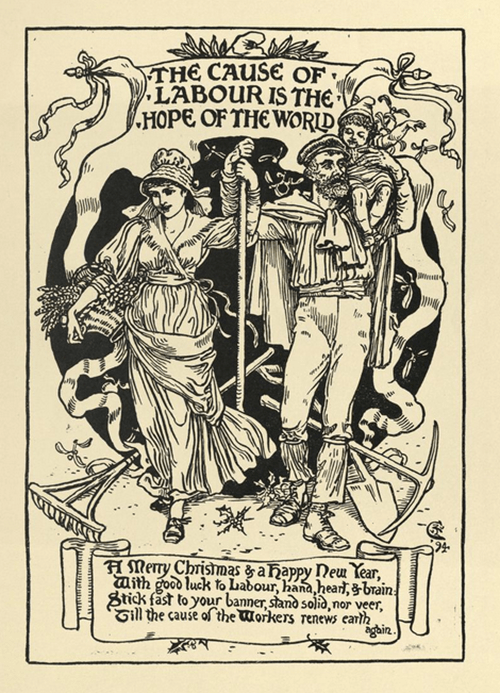

TOWARDS THE DAWN.

Let us, then, uphold the banner of art, with all its splendid traditions. The inseparable companion and complement of human life. May it display to us the spiritual form and ideal of the Socialist state, and ever present the living symbols of our hope and faith, and, by keeping these continually before our eyes, unobscured by temporary differences, confirm us in that unity of purpose and singleness of aim which are so essential to the advancement and success of our cause.

“For,” as William Morris says, “the hope of every creature is the banner that we bear.”

A long-running socialist paper begun in 1901 as the Missouri Socialist published by the Labor Publishing Company, this was the paper of the Social Democratic Party of St. Louis and the region’s labor movement. The paper became St. Louis Labor, and the official record of the St. Louis Socialist Party, then simply Labor, running until 1925. The SP in St. Louis was particularly strong, with the socialist and working class radical tradition in the city dating to before the Civil War. The paper holds a wealth of information on the St Louis workers movement, particularly its German working class.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/missouri-socialist/100625-stlouislabor-w490-DAMAGED.pdf