What the end of Reconstruction looked like in the North. Far more than a railroad strike or a series of major riots, what happened in 1877 remains unprecedented in U.S. history. A working class uprising that reached from coast to coast and involved many hundreds of thousands in desperate and bloody battles. Marxist labor historian Amy Schechter provides a fine introduction to those pivotal events, including a look at the St. Louis ‘Soviet’ which briefly flirted with workers’ rule only a few years after the Paris Commune.

‘The Labor Struggle of 1877’ by Amy Schechter from the Daily Worker (Saturday Supplement). Vol. 3 No. 158. July 17, 1926.

IN the years following the panic of 1873 conditions among the workers grew steadily worse. By 1877 the unemployed were estimated at 3,000,000. The death of workers from starvation became a familiar item in the day’s news and night after night police stations were thronged by families pleading for the shelter of a cell for the night. The employing class took advantage of the hard times and large army of unemployed to put over wage cut after wage cut, which the unions, greatly weakened by the long drawn-out depression, found it almost impossible to resist.

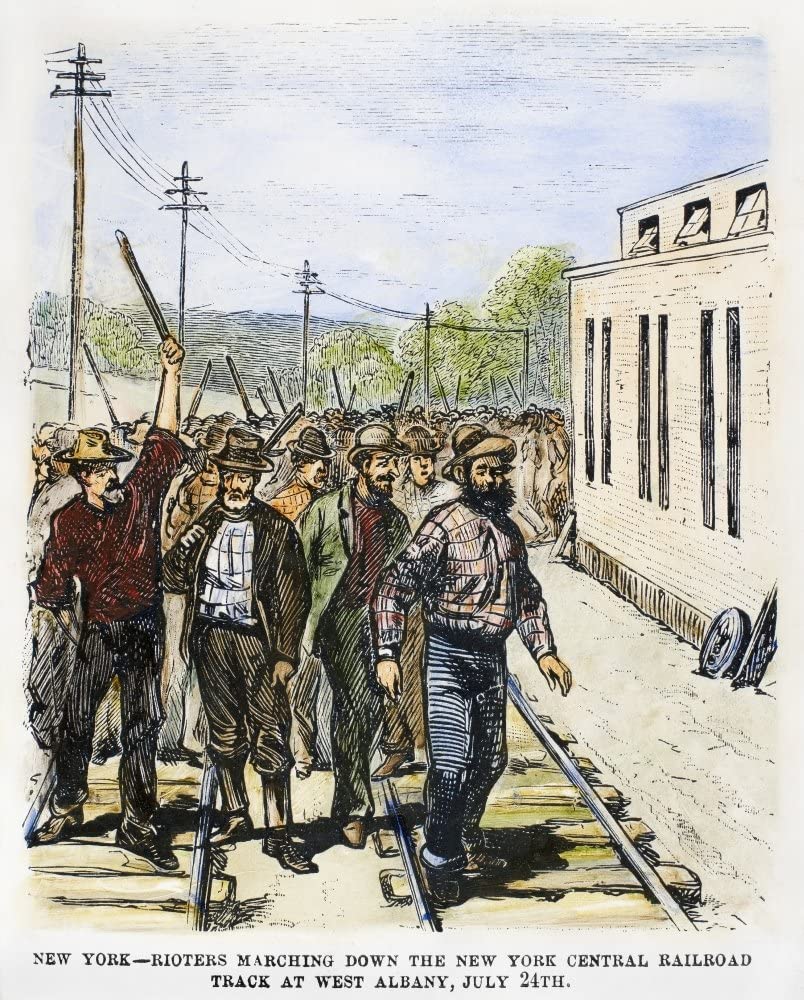

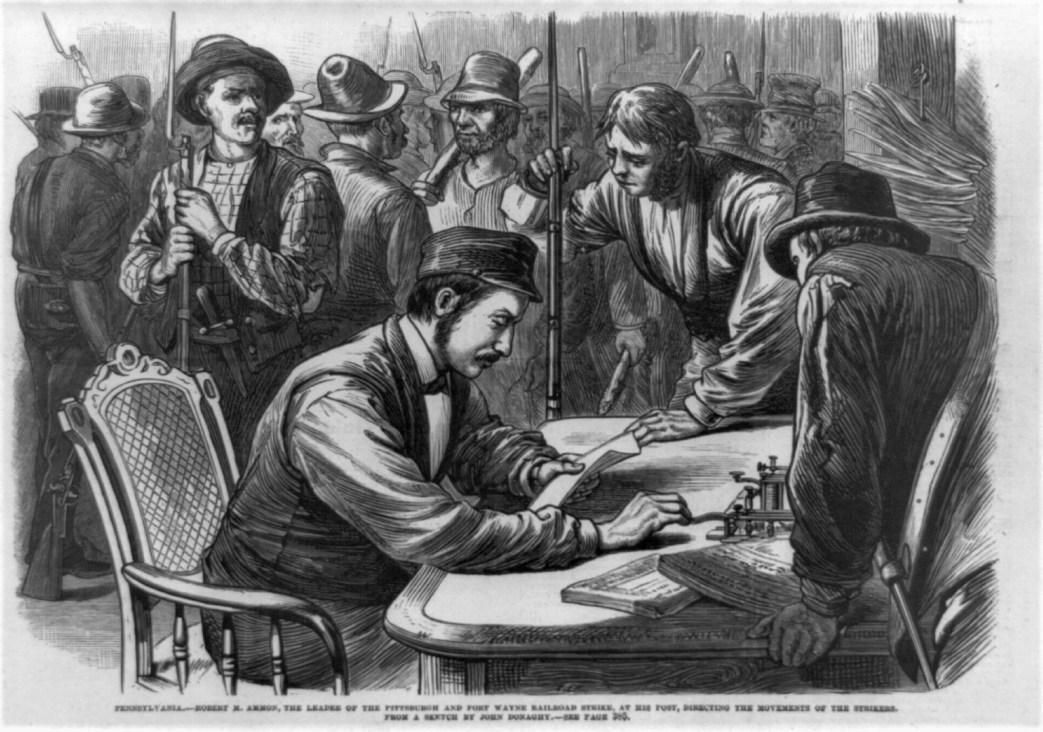

Early in ’77 a number of the great railroad corporations, several of which had only recently cut wages, announced further reductions to go into effect in the summer. An attempt was made by a rank and file committee organized by a young brakeman from men discontented with the lack of fight shown by union representatives chosen to treat with company officials, to form a secret union of all classes of rail workers on the three grand trunk lines to carry out a simultaneous strike against reductions.

Unfortunately, however, at the last moment dissension caused the committee to go to pieces, and the strikes that broke out from coast to coast were separate, spontaneous, and unorganized.

The first intimation of the violent struggle that was to spread from the Atlantic to the Pacific was on the Baltimore and Ohio road, which had announced a 10 per cent cut, the third in three years, to take effect on July 16. The men answered by walking out at Camden Point, Martinsburg and Cumberland, taking possession of the track and running freight trains onto sidings. The company officials appealed to the governor of West Virginia for troops in order to clear the railroad property of strikers and protect the scabs running the trains. The call was promptly answered, but since part of the state militia that were sent in fraternized with the strikers, and the rest found themselves helpless in the face of the strikers’ determined stand, not much was accomplished by this move. The governor now appealed to the president of the United States to put down the disorders, his appeal being supplemented by a personal one from the president of the B. & O. road. In answer President Hayes issued a proclamation commanding all strikers to retire by noon, July 19, on pain of dire penalties, which was completely ignored by the strikers, who did not let it interfere in the least with their plans. In addition, General French, in command at the Washington Arsenal, and General Barry from Fort Henry, were ordered to proceed with all avail- able troops to the threatened points. This was the first time that the national government had interfered in a strike, and the move created immense excitement among workers thruout the country.

THE central committee of the B. & O. strikers at Baltimore issued a circular stating the causes for the strike-that in addition to this being the third cut in three years, they often had only 15 days’ work a month; that when the trains were sent into Martinsburg they were kept there four days and forced to pay their own board, which amounted to more than their wages, leaving nothing for the support of their families; that when they thus fell into debt their wages were attached, which, according to company regulations, meant their immediate discharge.

By now the railroad men had been joined by large numbers of workers from the mills and factories of Baltimore. When word came on July 20 that the Fifth and Sixth Regiments of the Maryland National Guards were to be sent from the city to break the hold of the strikers along the railroad line, the Baltimore workers swore they should never leave the station. The militia, realizing the strength and determination of the crowd, being very slow in assembling at their armories, their commanding officer ordered the militia call to arms, 1-5-1, to be sounded through the city. The wild pealing of the alarm bells, last heard at the outbreak of the Civil War, aroused excitement to a tremendous pitch.

THE Sixth Regiment, finding their way blocked as they left their armory to go to the station, suddenly, without warning, fired a volley into the dense crowd. Maddened by the attack, the crowd charged the troops, attempting to overcome and disarm them, to be met by repeated fusillades.

Leaving numbers of dead and dying in their tracks, the troops managed to reach the station; but, fearing the wrath of the crowd, who had surrounded the station and dragged the engineer and fireman from the troop train, the commander abandoned the attempt to move the troops, and called upon Washington to take over the situation. The capital sent in General Barry, with artillery, and fifty of the leading strikers were captured and imprisoned. But the B. & O. had to announce officially that it would make no more attempts to run trains for the time being.

By this time the federal government seems to have been pretty thoroly frightened by the situation existing thruout the country, and considering the proximity of Baltimore, began to fear for its own safety. “Washington itself was considered to be in danger,” and the cabinet decided “that no further depletion of the military and naval forces at the capital ought to be made.” The fact that two companies of marines marching through the streets to entrain for the strike area were saluted there, in the capital itself, by a great crowd with groans and hisses, was not reassuring. The war vessels Swatara and Powhattan were directed to take on board the soldiers and marines stationed at Norfolk and proceed to the Potomac, the iron-clads at Washington, Philadelphia and other points were ordered to prepare for instant service; provision was made for the defense of the United States treasury, etc.

PENNSYLVANIA, with its great industrial population, “was in arms from the Delaware to the Monongahela.” Not only the railroaders, but thousands of miners were out, and there were armed clashes in all parts of the state. We read of miners marching from mine to mine to get the men out, with loaves of bread stuck on poles, and the war cry of “Bread or Blood.”

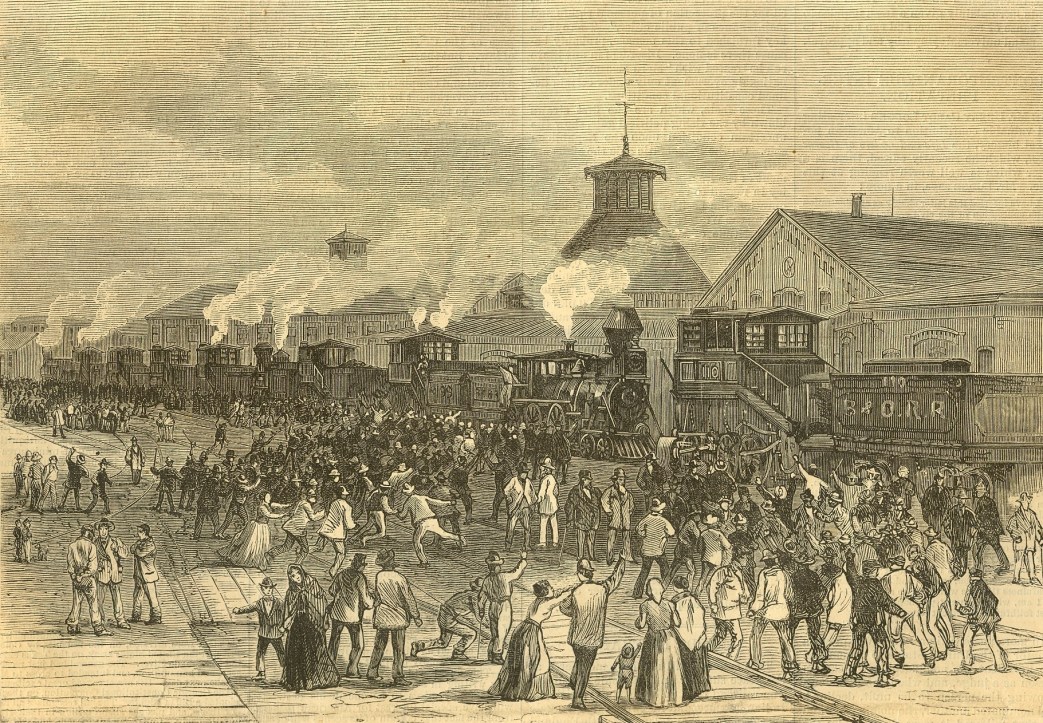

The Pennsylvania Railroad had already cut wages 10 per cent in June, and now they intended to introduce “double-headers” on the line; that is, freight trains made up of double the number of cars manned by crews of the same size as formerly. This involved the dismissal of hundreds of workers, and much more labor for the men who were retained.

On July 19, the date set for the introduction of the new system, the men struck, sending an ultimatum to the company in which they demanded, among other things: The same wages as before the cut, the abolition of the “double-headers” except on coal trains, no victimization of strikers, Following a conference with the strike committee at Pittsburgh, which resulted in a dead-lock, the strikers insisting they would treat only on the basis of their ultimatum, the officials demanding unconditional surrender. The latter sent the sheriff to arrest the leaders and raid strike headquarters. When strikers defied him the company asked the governor to send in troops. The threat of General Pear- son, commanding officer of the three regiments of Philadelphia state guards that came in answer to the call, that it was “useless to attempt to stop the working of the road, and the trains must go through,” was met with jeers and shouts of “Who are you?” and “Give us bread!”

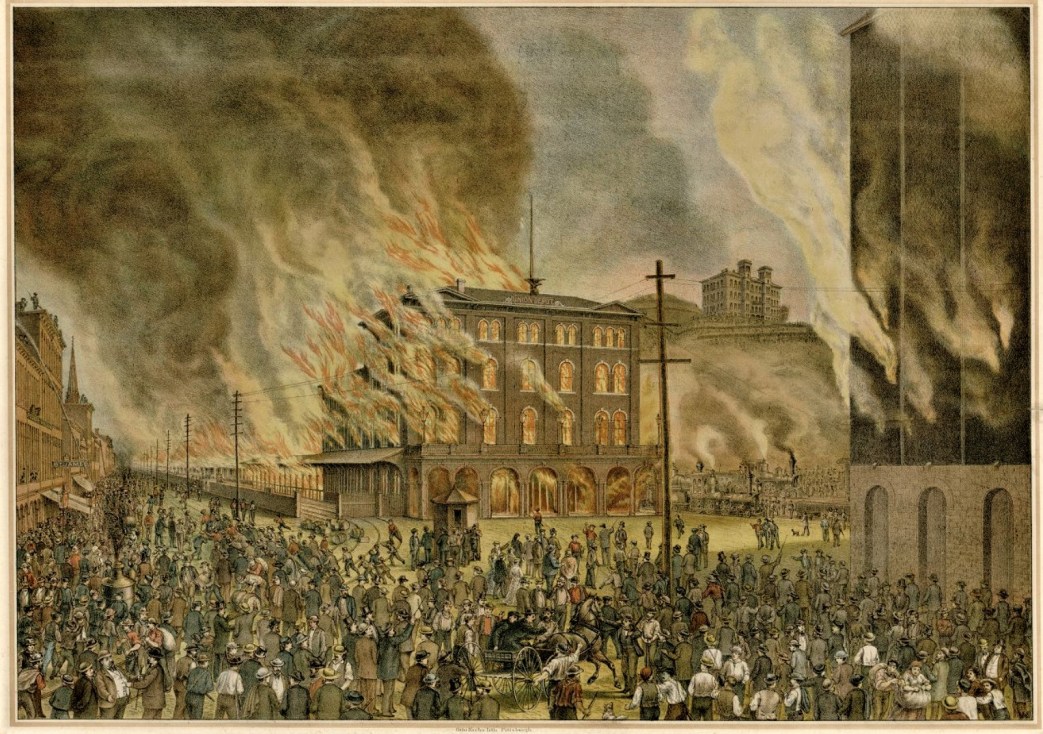

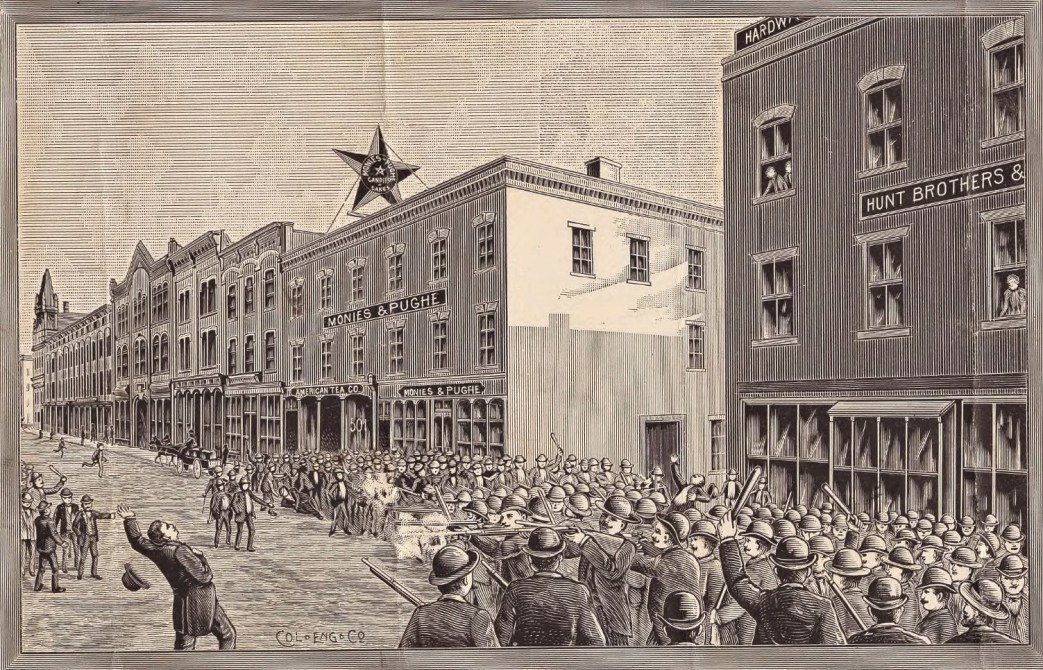

THE NEXT day the storm broke. The sheriff again went to arrest the strike leaders, this time under the protection of the Philadelphia troops. Thousands of workers barred the way -the railroaders had been joined by most of the workers in that city of workers. The sheriff read the riot act, and the troops immediately began firing into the crowd. The bloody battle of Baltimore was repeated, but here the local militia went over to the side of the strikers. A number of these fraternizing soldiers fell beneath the fire of the Philadelphia troops, and their slaughter helped to increase the bitterness of the population. The crowd broke into gun stores thruout the city, carrying off some $100,000 worth of arms-guns and swords and knives and pistols.

The Philadelphia troops had retreated to the railway roundhouse, and all night long the strikers tried to storm their refuge with two pieces of artillery captured earlier in the evening. Finally succeeding in making a breach in the walls, they tried to rush the building, but were forced back by the terrible concentrated fire of the troops within. Next the besiegers sent lighted cars of oil-soaked coke along the track toward the roundhouse, and soon it was in flames. The troops managed to escape from it under cover of a heavy artillery barrage, and after a fierce battle all along the line of retreat finally crossed the Allegheny River, never stopping till they reached Claremont, 12 miles beyond the city limits, where the strikers had vowed to drive them. The workers, who had suffered heavy losses, were now pretty well exhausted, and a vigilance committee that was formed at last managed to arrest the strike leaders. Two roundhouses and all the railroad shops had been destroyed, as well as some 1,600 cars and 125 locomotives.

IN Reading the whole Sixteenth Regiment, composed of Irish workers, went over to the strikers. They not only gave them their arms and ammunition, but, according to a reliable account, “they were repeatedly heard swearing that not only would they not fire upon the mob in any event, but if the Eastern Greys (who had shot down a number of workers before the Sixteenth reached the city) did so, they would fire upon them and help the rioters clean them out and burn the railroad’s property.” Also that “the only one they’d like to pour their bullets into was that damned Frank B. Gowen” (the superintendent of the railroad).

One of the strangest features of the strike, and the one of which least is known, is the mysterious St. Louis “Soviet,” set up under socialist-leadership. This “Soviet” sent out committees which closed up every shop and mill in the place, and for a week seems to have taken over most of the functions of government in the city. In their proclamations the executive committee spoke of themselves as “the authorized representatives of the industrial population of St. Louis.” Orders were issued providing for food distribution, medical attendance, etc. How representative the committee really was and what its composition was will be worth finding out some day. At any rate, the bourgeoisie of the city were panic-stricken at its appearance-the spectre of the Paris Commune, then only seven years past, continually haunted the ruling classes of that period as the spectre of the Russian revolution does the ruling class of today.

THEY formed a committee of safety, and, after a week of the “Soviet’s” rule-and from all available accounts its control seems to have been almost absolute-raided its headquarters with cavalry and infantry and artillery, some 600 in all. Seventy-three men were found in the building and arrested, “a body of sinewy men, toil-worn and grim, clad in rough garments such as laborers wear,” a reporter who accompanied the raiders describes them.

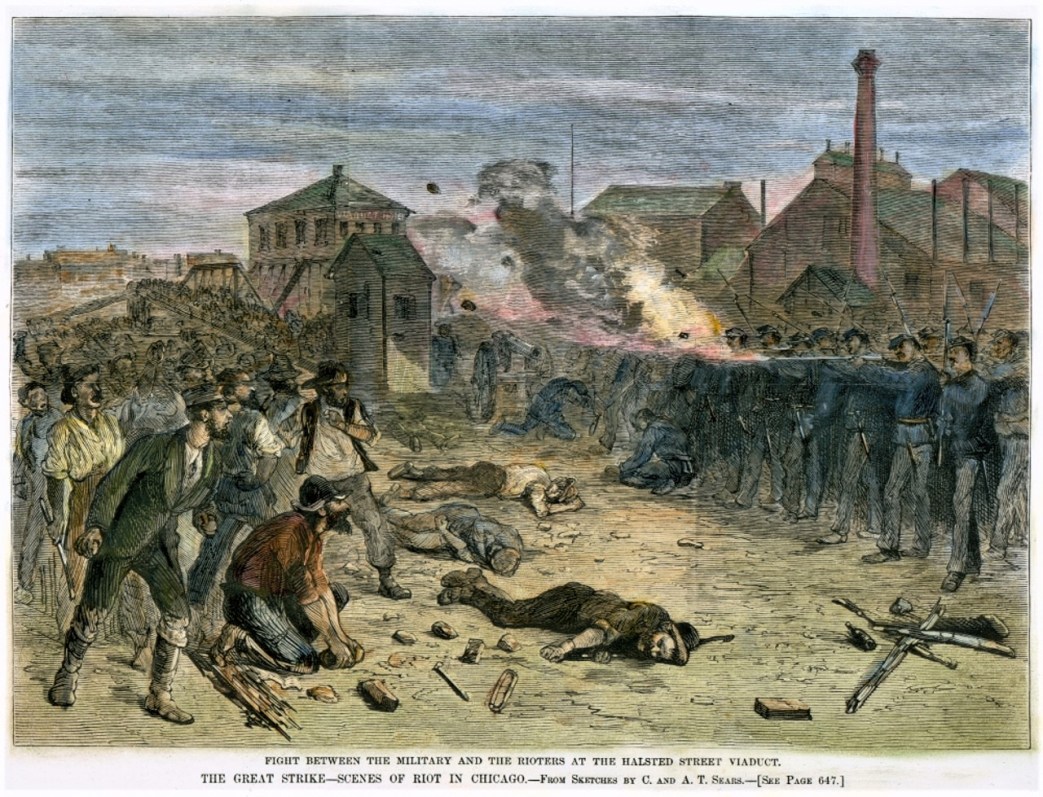

The one other city in which socialist influence seems to have counted at all in the strike was Chicago. There the strike agitation was conducted, according to Hillquit, under the direct supervision of the party national executive of the Workingman’s Party (later the S.L.P.). The leading spirit was the same Parsons, then a compositor on the Chicago Times, who in 1886 was murdered by the government as one of the “Chicago anarchists,” and who even at that time the government had begun to fear and wish out of the way. The fighting centered round the South Side railroad yards, with a pitched battle between federal troops and workers at the Halsted street viaduct. In Chicago a number of railroad companies finally acceded to the strikers’ demands, and the city council appropriated $500,000 for public improvement to provide work for the unemployed.

As to the final results of this tremendous outpouring of energy and heroism, this swift flaming of revolutionary passion, it is, perhaps, best to quote Sorge, the brilliant co-worker of Karl Marx, who did a great deal to- wards laying the foundations of the revolutionary movement in the United States.

“The whole movement,” he wrote, “was the spontaneous outbreak of the anger and discontent of the workers, and those sections of the population standing nearest to them, with their miserable conditions of life and with the appalling mismanagement of the ruling classes. And, as in practically every spontaneous movement, the numerous victories of the workers in many sections of the country brought them no lasting gain, because they lacked the organization necessary to profit from their victories.” (Neue Zeit, V. 10, 1892.)

This fatal lack seems to have been brought home to labor to a marked extent in the course of the struggle, and afterwards, when capitalism began a savage warfare on what was left of the old unions, reviving the old conspiracy laws, extending the use of the courts as an instrument against the workers, and making, open military preparation for the next struggle that might arise. The Knights of Labor began to grow enormously in strength, but, above all, the socialist movement began to break away from its isolation and to gain a foothold among the masses, and for the first time the workers to awaken to the consciousness of the necessity of a mass party to lead them in their war with capitalism.

The Saturday Supplement, later changed to a Sunday Supplement, of the Daily Worker was a place for longer articles with debate, international focus, literature, and documents presented. The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1926/1926-ny/v03-n158-supplement-jul-17-1926-DW-LOC.pdf