A classic piece of radical reporting from John Reed as he covers the 1918 Chicago conspiracy mass-trial of the I.W.W. with no less than Art Young along as courtroom sketch artist.

‘The Social Revolution In Court’ by John Reed from The Liberator. Vol. 1 No. 7. September, 1918.

IN the opening words of his statement why sentence of upon Spies, to who one of the Chicago martyrs of 1887, quoted the speech of a Venetian doge, uttered six centuries ago—

“I stand here as the representative of one class, and speak to you, the representatives of another class. My defense is your accusation; the cause of my alleged crime, your history.”

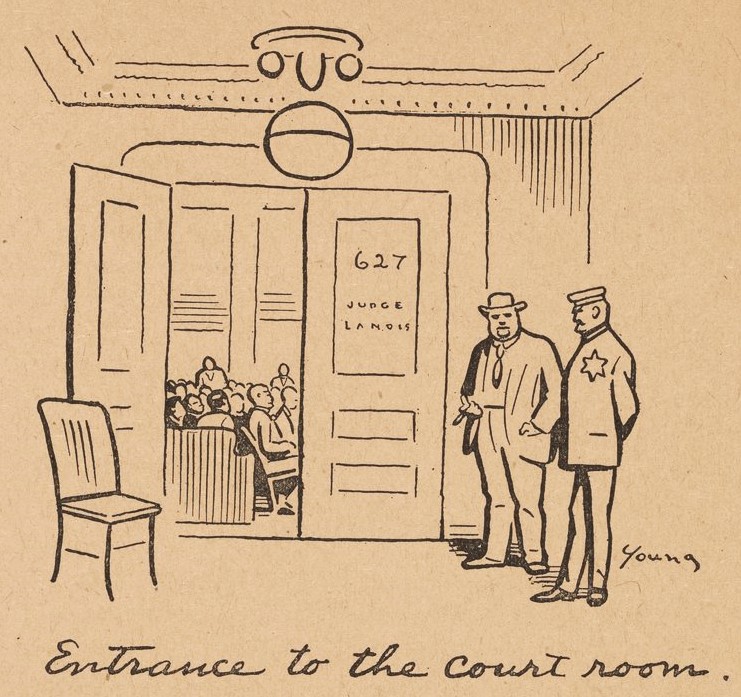

The Federal court-room in Chicago, where Judge Landis sits in judgment on the Industrial Workers of the World, is an imposing great place, all marble-and-bronze and mellow dark wood-work. Its windows open upon the heights of towering office-buildings, which dominate that court-room as money-power dominates our civilization.

Over one window is a mural painting of King John and the Barons at Runnymede, and a quotation from the Great Charter:

“No freeman shall be taken or imprisoned or be disseized of his freehold or liberties or free customs, or be outlawed or exiled or any otherwise damaged but by lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land-

“To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay right or justice…“

Opposite, above the door, is printed in letters of gold:

“These words the Lord spake unto all your assembly in the mount out of the midst of the fire, of the cloud, and of the thick darkness, with a great voice; and he added no more. And he wrote them in two tables of stone, and delivered them unto me. “- Deut. V. 22.

Heroic priests of Israel veil their faces, while Moses elevates the Tables of the Law against a background of clouds and flame.

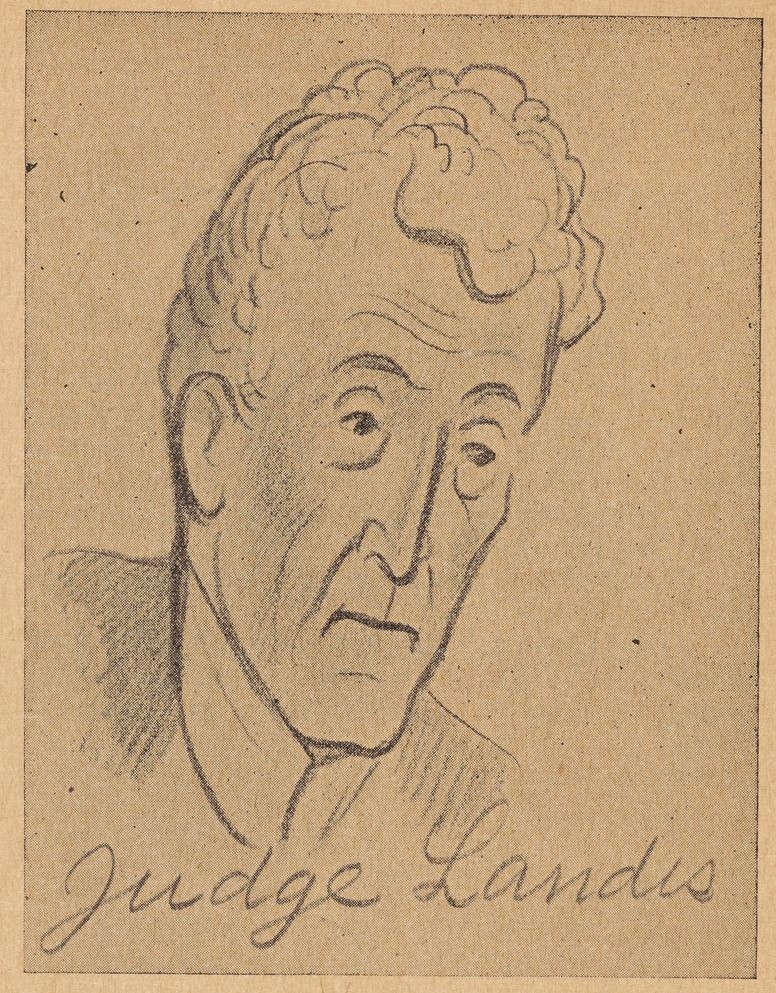

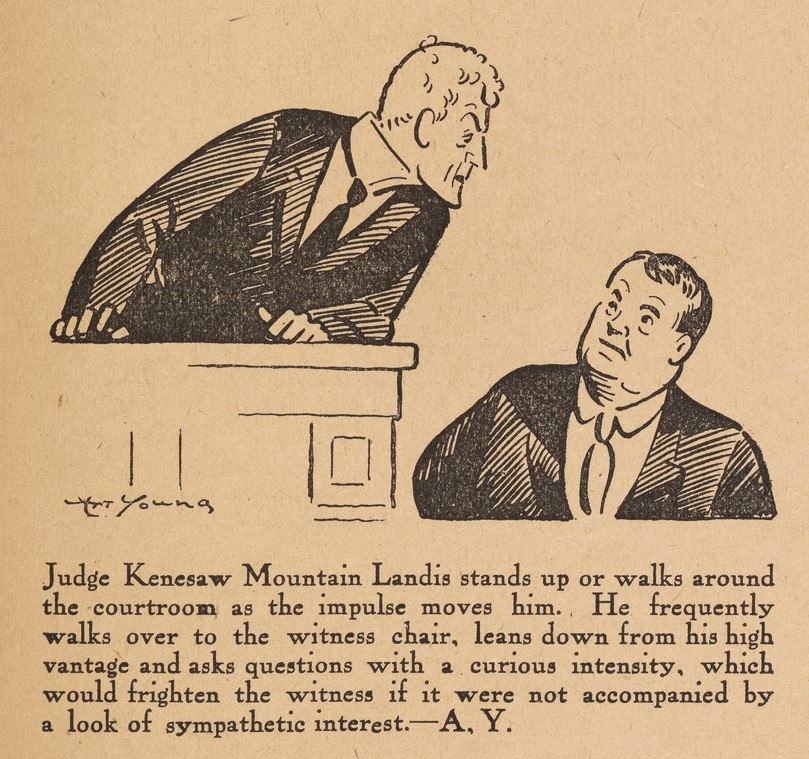

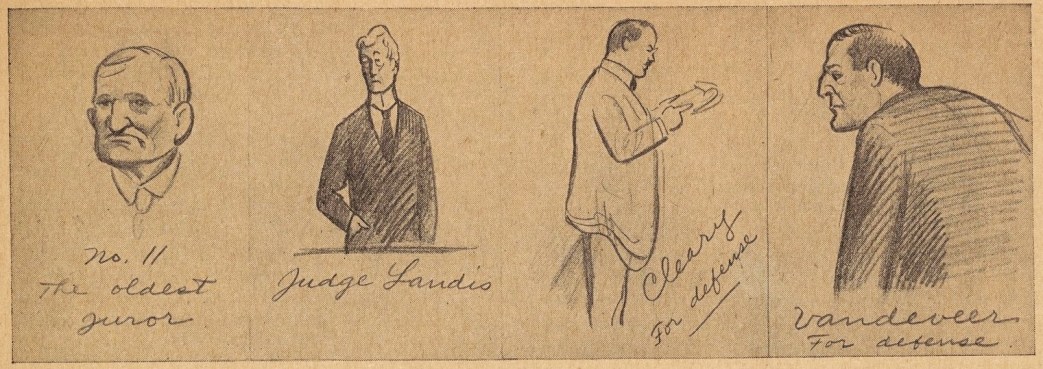

Small on the huge bench sits a wasted man with untidy white hair, an emaciated face in which two burning eyes are set like jewels, parchment skin split by a crack for a mouth; the face of Andrew Jackson three years dead. This is Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, named for a battle- a fighter and a sport, according to his lights, and as just as he knows thirty-nine million dollars. (No, none of it was paid.)

Upon this man has devolved the historic role of trying the Social Revolution. He is doing it like a gentleman. Not that he admits the existence of a Social Revolution. The other day he ruled out of evidence the Report of the Committee on Industrial Relations, which the defense was trying to introduce in order to show the background of the I.W.W.

“As irrelevant as the Holy Bible,” he said. At least that shows a sense of irony.

In many ways a most unusual trial. When the judge enters the court-room after recess no one rises- he himself has abolished the pompous formality. He sits without robes, in an ordinary business suit, and often leaves the bench to come down and perch on the step of the jury box. By his personal order, spittoons are placed beside the prisoners’ seats, so they can while away the long day with a chaw; and as for the prisoners themselves, they are permitted to take off their coats, move around, read newspapers.

It takes some human understanding for a Judge to fly in the face of judicial ritual as much as that…

As for the prisoners, I doubt if ever in history there has been a sight just like them. One hundred and one men- lumber-jacks, harvest-hands, miners, editors; one hundred and one who believe that the wealth of the world belongs to him who creates it, and that the workers of the world shall take their own. I have before me the chart of their commonwealth- their industrial democracy- One Big Union.

One Big Union- that is their crime. That is why the I.W.W. is on trial. In the end just such an idea shall sap and crumble down capitalist society. If there were a way to kill these men, capitalist society would cheerfully do it; as it killed Frank Little, for example-and before him, Joe Hill…So the outcry of the jackal press, “German agents! Treason!”- that the I.W.W. may be lynched on a grand scale.

One hundred and one strong men. Most of our American social revolutionists are in the sedentary trades- garment-workers, textile-workers, printers. At least, so it seems to us, in the great cities. Your miners, your steel and iron workers, building-trades, railroad workers-all these belong to the A.F. of L., which believes in the capitalist system as strongly as J.P. Morgan does. But these Hundred and One are out-door men, hard-rock blasters, tree-fellers, wheat-binders, longshoremen, the boys who do the strong work of the world. They are scarred all over with the wounds of industry- and the wounds of society’s hatred. They aren’t afraid of anything. They are the kind of men the capitalist points to as he drives past some great building they are putting up, or some huge bridge they are throwing over a river:

“There,” he says, “that’s the kind of working-men we want in this country. Men that know their job, and work at it, instead of going around talking bosh about the class struggle.”

They know their job, and work at it. But strangely enough they believe in the Social Revolution too. Hear this once more, their trumpet-call; the famous Preamble of the I.W.W.:

“The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of working-people, and the few who make up the employing class have all the good things of life.

“Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organize as a class, take possession of the earth and the machinery of production, and abolish the wage system.”

Jail, where most of them have been rotting three-quarters of a year, and march into the court-room two by two, between police and detectives, bailiffs snarling at the spectators who stand too close. It used to be that they were marched four times a day through the streets of Chicago, hand-cuffed; but the daily circus parade has been done away with.

Now they file in, the ninety-odd who are still in jail, greeting their friends as they pass; and there they are joined by the others, those who are out on bail. The bail is so high- from $25,000 apiece down- that only a few can be let free. The rest have been in that horrible jail- Cook County since early last fall; almost a year in prison for a hundred men who love freedom more than most.

On the front page of the Daily Defense Bulletin, issued by headquarters, is a drawing of a worker behind the bars, and underneath, “REMEMBER! We are in HERE for YOU; You are out THERE for US!”

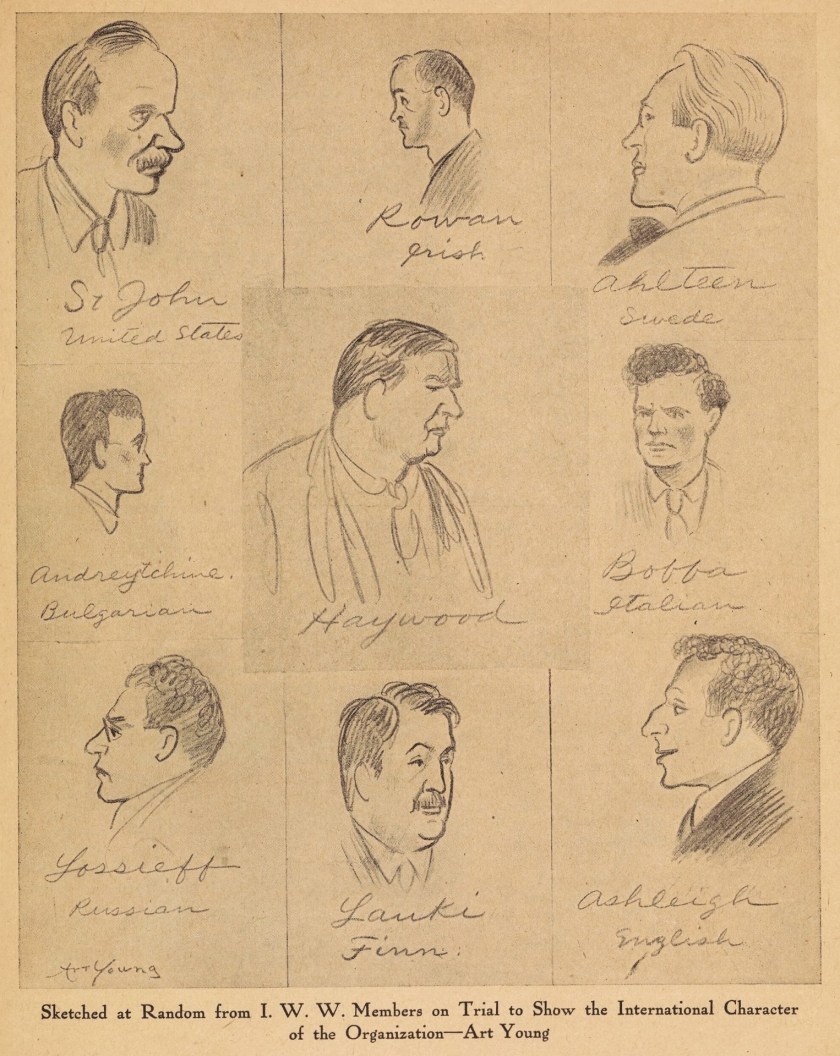

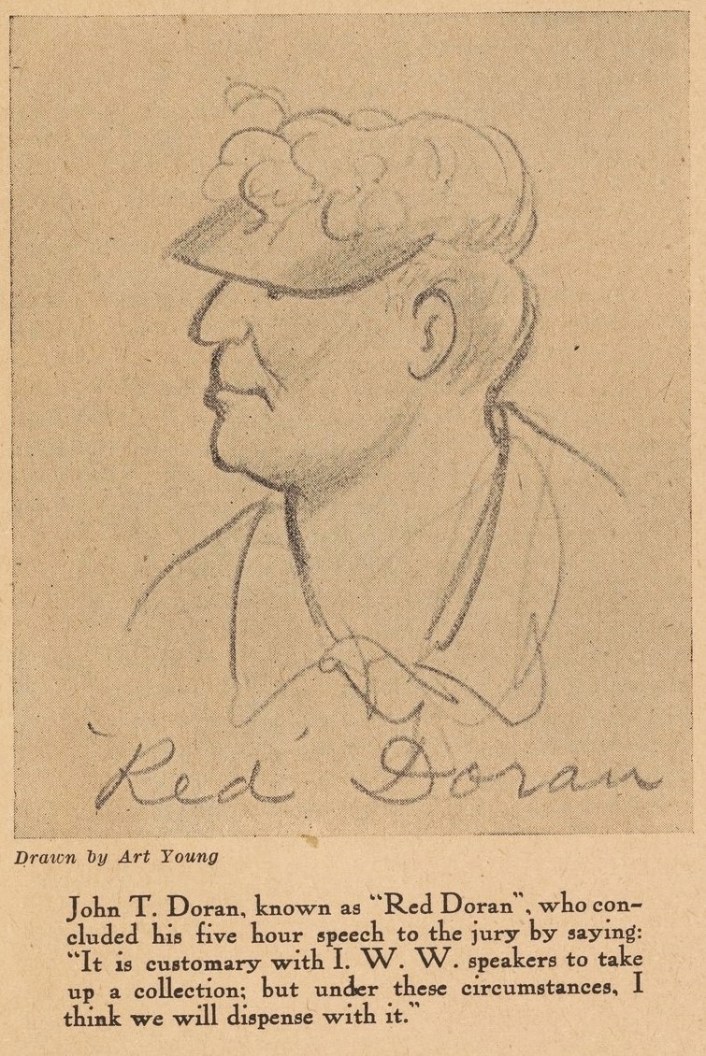

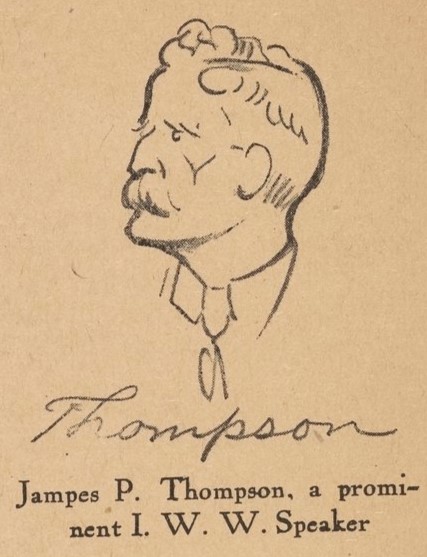

There goes Big Bill Haywood, with his black Stetson above a face like a scarred mountain; Ralph Chaplin, looking like Jack London in his youth; Reddy Doran, of kindly pugnacious countenance, and mop of bright red hair falling over the green eye-shade he always wears; Harrison George, whose forehead is lined with hard thinking; Sam Scarlett, who might have been a yeoman at Crecy; George Andreytchine, his eyes full of Slav storm; Charley Ashleigh, fastidious, sophisticated, with the expression of a well-bred Puck; Grover Perry, young, stony-faced after the manner of the West; Jim Thompson, John Foss, J. A. MacDonald; Boose, Prancner, Rothfisher, Johanson, Lossiev…

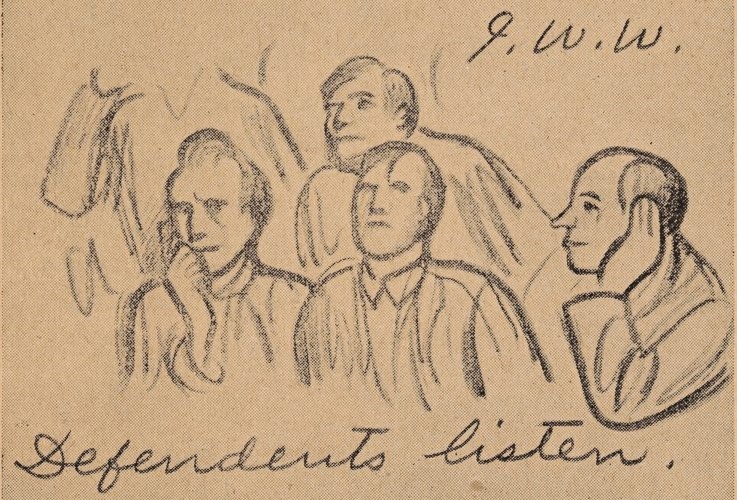

Inside the rail of the court-room, crowded together, many in their shirt-sleeves, some reading papers, stretched out asleep, some sitting, some standing up; the faces of workers and fighters, for the most part, also the faces of orators, of poets, the sensitive and passionate faces of foreigners-but all strong faces, all faces of men inspired. In the early morning they come over from Cook County somehow; many scarred, few bitter. There could not be gathered together in America one hundred and one men more fit to stand for the Social Revolution. People going into that court-room say, “It’s more like a convention than a trial!” True, and that is one of the things that gives the trial its dignity; that, and the fact that Judge Landis conducts it in a cosmic way.

To me, fresh from Russia, the scene was strangely familiar. For a long time I was puzzled at the feeling of having witnessed it all before; suddenly it flashed upon me. The I.W.W. trial in the Federal court-room of Chicago looked like a meeting of the Central Executive Committee of the All-Russian Soviets of Workers’ Deputies in Petrograd! I could not get it into my head that these men were on trial. They were not at all cringing, or frightened, but confident, interested, humanly understanding…like the Bolshevik Revolutionary Tribunal…For a moment it seemed to me that I was watching the Central Committee of the American Soviets trying Judge Landis for, well, say counter-revolution. The great enclosure of the court-room assumed the character of delegates’ seats; the high bench was the bar, or docket, whose one occupant, Judge Landis, was typical of the old régime- the best of the old régime.

And then I noticed the clumps of heavy, brutish-faced men, built like minotaurs, whose hips bulged, and whose little eyes looked mingled ferocity and servility, like a bulldog’s; the look of private detectives, and scabs, and other body-guards of private property…

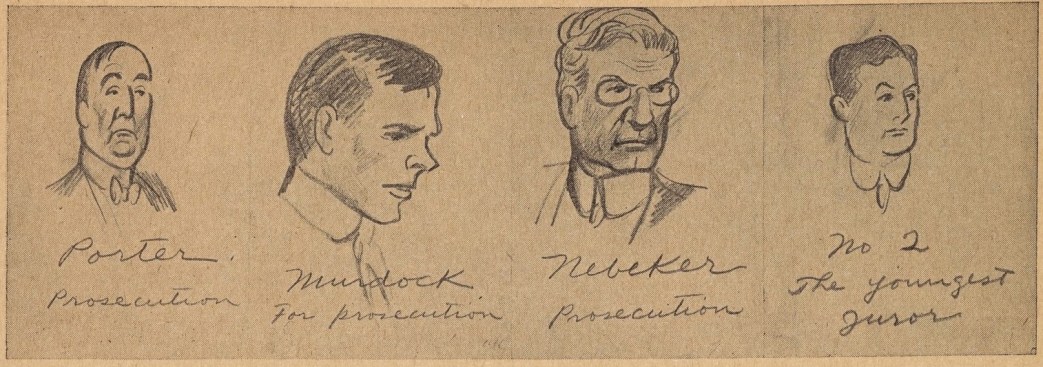

And I saw the government prosecutor rise to speak- Attorney Nebeker, legal defender for the great copper-mining corporations; a slim, nattily-dressed man with a face all subtle from twisting and turning in the law, and eyes as cold and undependable as flawed steel.

And I looked through the great windows and saw, in the windows of the office-buildings that ringed us round, the lawyers, the agents, the brokers at their desks, weaving the fabric of this civilization of ours, which drives men to revolt and dream, and then crushes them. From the street came roaring up the ceaseless thunder of Chicago, and a military band went blaring down invisible ways to war.

Talk to us of war! These hundred and one are veterans of a war that has gone on all their lives, in blood, in savage and shocking battle and surprise; a war against a force which has limitless power, gives no quarter, and obeys none of the rules of civilized warfare. The Class Struggle, the age-old guerilla fight of the workers against the masters, world- wide, endless…but destined to end!

These hundred and one have been at it since in their youth they watched their kind being coldly butchered, not knowing how to resist. They have mastered the secret of war- take the offensive! And for that knowledge they are hunted over the earth like rats.

In Lawrence a policeman killed a woman with a gun, a militia-man bayoneted a boy; in Paterson the private-detective-thugs shot and killed a worker standing on his own porch, with his baby in his arms; on the Mesaba Range armed guards of the Steel Trust murdered strikers openly, and other strikers were jailed for it; in San Diego men who tried to speak on the streets were taken from the city by prominent citizens, branded with hot irons, their ribs caved in with baseball bats; in the harvest fields of the great Northwest workers were searched, and if red cards were found on them, cruelly punished by vigilantes. At Everett, the hirelings of the Lumber Trust massacred them.

The creed of the I.W.W. took hold mostly among migratory workers, otherwise unorganized; among the wretchedly exploited, the agricultural workers, timber-workers, miners, who are viciously underpaid and over-worked, who have no vote, and are protected by no union and no law, whose wage and changing abode never allow them to marry, nor to have a home. The migratory workers never have enough money for railway fares; they must ride the rods, or the “side-door Pullman”; fought not only by Chambers of Commerce, Manufacturers’ Associations, and all the institutions of the law, but also by the aristocratic labor unionists. The natural prey of the world of vested interest; of this stuff the I.W.W. is building its kingdom. Good stuff, because tried and refined; without encumbrances; willing to fight and able to take care of itself; chivalrous, adventurous. Let there be a “free speech fight” on in some town, and the “wobblies converge upon it, across a thousand miles, and fill the jails with champions.

And singing. Remember, this is the only American working-class movement which sings. Tremble then at the I.W.W., for a singing movement is not to be beaten.

When you hear out of a freight train rattling across a black-earth village street somewhere in Iowa, a burst of raucous, ironical young voices singing:

“O I like my boss,

He’s a good friend of mine,

And that’s why I’m starving

Out on the picket-line!

Hallelujah! I’m a bum!

Hallelujah! Bum again! Hallelujah!

Give us a hand-out

To revive us again!”

When at hot noon-time along the Philadelphia waterfront you hear a bunch of giants resting after their lunch, in the most mournful barbershop rendering that classic:

“Whadda Ye Want Ta Break Yer Back Fer the Boss For?”

Or,

“Casey Jones-The Union Scab.”

I can hear them now:

“Casey Jones kept his junk pile running,

Casey Jones was working double time;

Casey Jones, he got a wooden medal

For being good and faithful on the S.P. line!”

When you hear these songs you’ll know it is the American Social Revolution you are listening to.

They love and revere their singers, too, in the I.W.W. All over the country workers are singing Joe Hill’s songs, “The Rebel Girl,” “Don’t Take My Papa Away From Me,” “Workers of the World, Awaken.” Thousands can repeat his “Last Will,” the three simple versus written in his cell the night before execution. I have met men carrying next their hearts, in the pocket of their working-clothes, little bottles with some of Joe Hill’s ashes in them. Over Bill Haywood’s desk in National headquarters is a painted portrait of Joe Hill, very moving, done with love…I know no other group of Americans which honors its singers. Not only popular singers, but also painters, musicians, sculptors, poets. This for example by Charles Ashleigh:

TO BEAUTY

“Your name, they say, is pale and old,

And speaking of you leaves men cold.

New things, they say, have filled your place;

New thoughts and words, across the space

Of swaying time, have marched and sat

In the high place we worshipped at.

But still for me your name can sing

A hymn that blots my cavilling,

An ecstasy that rocks my heart

And tears the squalid veil apart.

So long as I can feel your reign

And sense your holiness again,

I’ll throw my youth into your hands

And bear your glory through the lands.”

Wherever, in the West, there is an I.W.W. local, you will find an intellectual center-a place where men read philosophy, economics, the latest plays, novels; where art and poetry are discussed, and international politics. In my native place, Portland, Oregon, the I.W.W. hall was the livest intellectual center in town. There are playwrights in the I.W.W. who write about life in the jungles,” and the “wobblies ” produce the plays for audiences of wobblies.”

What has all this to do with the trial in Chicago? I plead guilty to wandering from the point. I wanted to give some of the flavor that sweetens the I.W.W. for me. It was my first love among labor organizations; I have had the honor of being arrested in an I.W.W. strike, and of being in jail with Bill Haywood and other worker-champions for a few days. I shall never forget the impression made on me by a young Italian striker, who read Robert Ingersoll eagerly aloud in the jail; and by Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, then at the height of her rebel beauty; and Carlo Tresca, one of the biggest souls in the world’s labor movement; and Arturo Giovanitti, who writes English poetry to my mind more magnificently than any English-speaking poet…

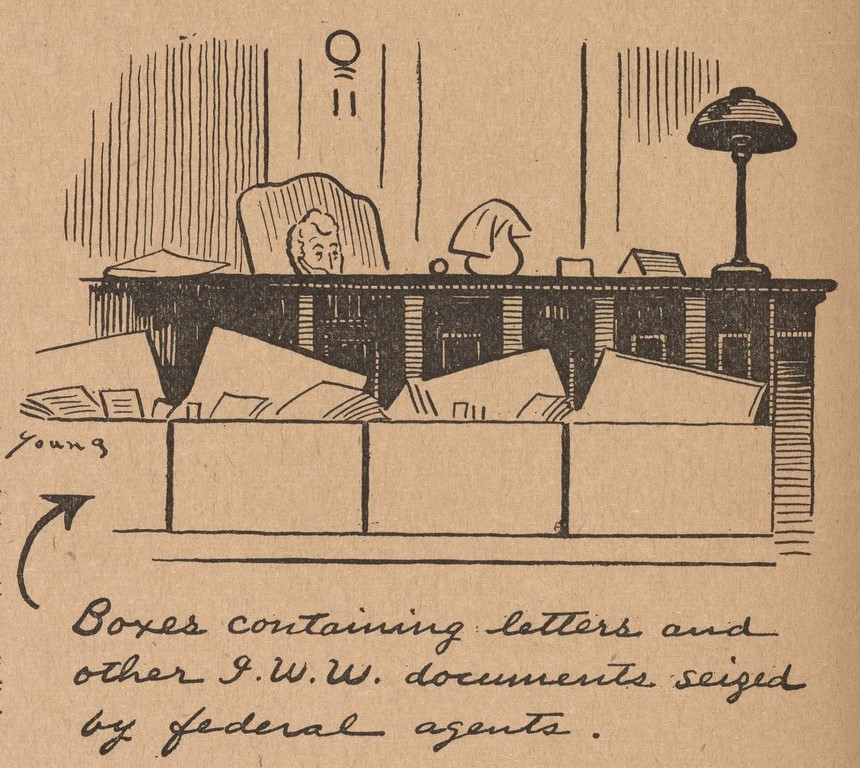

It was in September, 1917, that the I.W.W. manhunt began. From that time until April, 1918- seven months- the boys lay in jail, waiting for trial. They were charged with being members of an organization, and conspiring to promote the objects of this organization, which were, briefly, to destroy the wage-system- and not by political action. All this leading inevitably to the “destruction of government in the United States”…This main count in the indictment would have been highly ludicrous if it hadn’t been mixed up with the sinister “obstructing the War Program of the Government”; and there were dragged in the twin sins of Sedition and Opposing the Draft…

And while the hundred and twelve were rotting in jail, a ferocious hunt was launched throughout the country. I.W.W. halls were raided, conventions jailed; papers were seized; workers were herded into bull-pens by the thousand; and every organization of police, volunteer or regular, joined the campaign of violence and terrorization against the I.W.W., so widely labelled as German agents.

Of course the “Treason” phase of the case broke down completely. It was only inserted to disguise the real nature of the prosecution, anyway. The blood-curdling revelations of German intrigue promised the world by the prosecution at the opening of the trial did not materialize. The Government experts who examined the books and accounts of the organization admitted that all was in order. Finally, it was not proven that there was an I.W.W. policy concerning the war, or even concerted opposition of opinion to Conscription….

Among other farcical incidents was the loudly-heralded arrival in Chicago of ex-Governor Tom Campbell of Arizona, with a “suitcase full of proofs that the I.W.W. was paid by Germany.” For weeks he stood off and on, waiting to be called to the witness-stand. Then of a sudden he announced in the newspapers that the famous “suit-case” had been stolen by an I.W.W. disguised as a Pullman porter!…

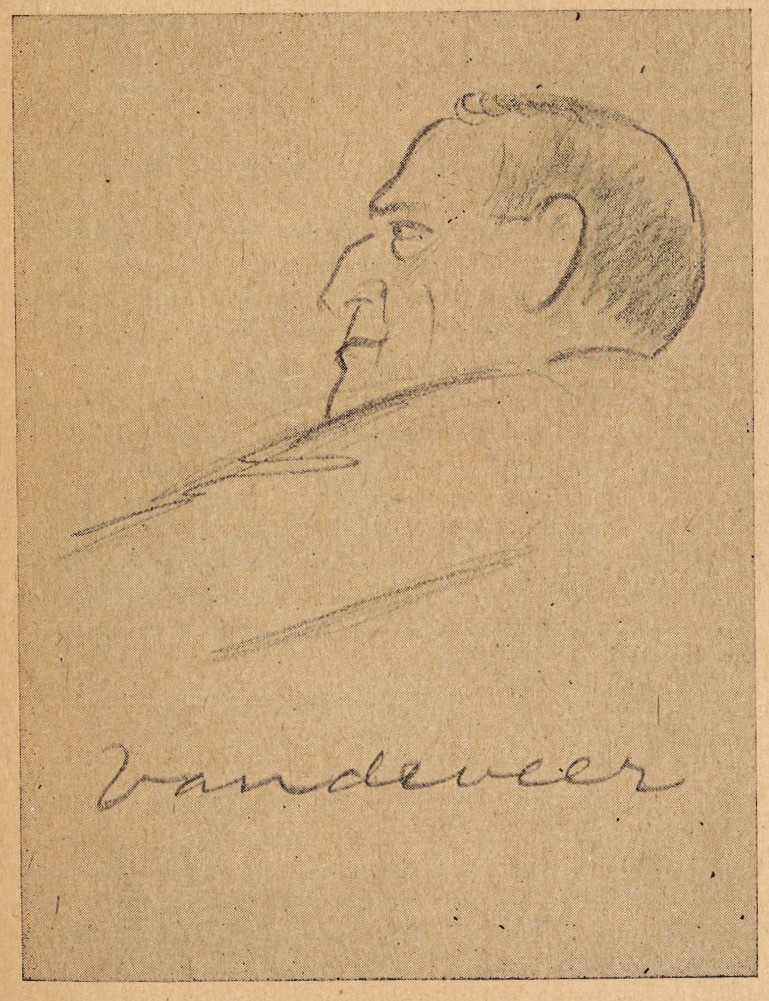

In order that there should be no opportunity for sentimentality, the prosecution dismissed all indictments against women defendants; in order that the I.W.W. should not be able to testify about the worst outrages perpetrated against the workers, not one of the Bisbee deportees was put on trial, and not one of the Butte strikers who might testify to the “Speculator” mine fire…But because of the latitude allowed by Judge Landis, and the skill of Vandeveer and Cleary, the defense has been one long bloody pageant of industrial wrong; Coeur d’Alene, San Diego, Everett, Yakima Valley, Paterson, Mesaba Range, Bisbee, Tulsa…

From the very beginning, behind shallow legal pretexts loomed the Class Struggle, stark and implacable. The first battle was in the choice of a jury, which dramatically revealed the position of both sides. In examining talesmen, the attorneys for the prosecution asked such questions as these:

“Can you conceive of a system of society in which the workers own and manage industry themselves?”

“Do you believe in the right of individuals to acquire property?”

“You believe, do you not, that all children should be taught respect for other people’s property?”

“You believe, do you not, that the founders of the American Constitution were divinely inspired?”

“Don’t you think that the owner of an industry ought to have more say-so in the management of it than all his employees put together?”

Any prospective juror who admitted a familiarity with Labor history, with economics, or with the evolution of social movements, was peremptorily challenged by the prosecution. The questions of the defense were invariably objected to, and the prosecution made a series of extraordinary speeches to the court, in which were remarks such as the following:

“Karl Marx, father of that vicious doctrine- the cesspool into which the roots of the I.W.W. have gone for much nourishment.”

“This case is an ordinary criminal case, in which a number of men conspired to break the law…Their crime consists in the fact that they conspired to take from the employer what is constitutionally his, and in the ownership of which the law supports him.”

“The wage system,” said Mr. Clyne, of the prosecution, “is established by law, and all opposition to it is opposition to law.”

Another time Attorney Nebeker delivered himself of the following: “A man has no right to revolution under the law.” To which Judge Landis himself made remark, “Well, that depends on how many men he can get to go in with him- in other words, whether he can put it over.”

The defense sternly held to the Class War issue. Among questions asked the jurymen by Vandeveer and Cleary were:

“You told Mr. Nebeker that you had never read any revolutionary literature. Have you never read, in school, about the American Revolution of 1776? Or the French Revolution which deposed the king and made France a republic? Or the Russian Revolution that overthrew the autocracy and the Tsar?”

“Do you recognize the right of people to revolt?”

“Do you recognize the idea of revolution as one of the principles of the Declaration of Independence?”

“You have told Mr. Nebeker that you don’t think it is right to take away property from those who own it. In our own Civil War, do you think it was right for Congress to pass a law which took away from the people of the South several million dollars’ worth of property in the form of chattel slaves- without compensation?”

“You don’t believe then that property interests are greater than human interests?”

Suppose these defendants believed that a majority of the people would be right in abolishing modern property rights in the great industries in order to free a great number of working-men from industrial slavery, would that prejudice you against them?”

“Do you believe workers have the right to strike?”

“Do you believe they have the right to strike even in war times?”

“Which side usually starts violence in a labor dispute?”

“Would you be opposed to the application to industry of the underlying principles of American democracy?”

“Do you consider that one individual has an inalienable right to exploit 200 or 300 men and make protected profits off their labor?”

“Don’t you know that 2 per cent of the people of this country control 60 per cent of the nation’s wealth? That two-thirds of the people own less than 5 per cent of the country’s wealth?”

“Do you know that one man had a greater income last year than the combined income of 2,500,000 other Americans?”

“Do you know what effect the wage system has had upon infant mortality?”

“Do you know that prostitution is largely caused by the fact that women in industry do not receive living wages?”

“Do you believe in slavery-whether it be chattel slavery, where the master owned the worker body and soul, or whether it be industrial slavery?”

And so on, for a whole month. What an education that jury had; and what an education the whole country would have had, except that the jackal press has “hushed up” or perverted utterly the story of the I.W.W. trial. Publicity could not help but win the case for the “wobblies “; and so the great prostituted newspapers ignore the most dramatic legal battle since Dred Scott- one whose implications are as serious, and whose sky banked with thunderheads.

Day after day, all summer, witness after witness from the firing-line of the Class Struggle has taken the stand, and helped to shape the great labor epic; strike-leaders, gunmen, rank and file workers, agitators, deputies, police, stool-pigeons, Secret Service operatives.

I heard Frank Rogers, a youth grown black and bitter, with eyes full of vengeance, tell briefly and drily of the Speculator mine fire, and how hundreds of men burned to death because the company would not put doors in the bulkheads. He spoke of the assassination of Frank Little, who was hung by “vigilantes” in Montana, and how the miners of Butte swore to remember…(In the General Headquarters of the I.W.W. there is a death mask of Frank Little, blind, disdainful, set in a savage sneer.)

Oklahoma, the tar-and-feathering of the workers at Tulsa; Everett, and the five graves of Sheriff McRae’s victims on the hill behind Seattle all this has come out, day by day, shocking story on story. I sat for the better part of two days listening to A.S. Embree telling over again the astounding narrative of the Arizona deportations; and as I listened, looked at photographs of the miners being marched across the arid country, between rows of men who carried rifles in the hollow of their arms, and wore white handkerchiefs about their wrists.

Everyone knows how the deportees were loaded on cattle cars, how the engineer, protesting, was forced to pull the train out, and how finally, arriving at Columbus, New Mexico, the train was ordered back and finally halted in the desert, where United States troops saved the wretched people from exposure and starvation. Many of the deportees had wives, families and property in Bisbee, some were not I.W.W.’s at all, and others had no connection with the labor movement in any way; a large number of the men owned Liberty bonds, and many were registered in the Draft.

At first the committee of the deportees telegraphed to Wiley E. Jones, Attorney General of the State of Arizona, as follows:

“Sentiment of the men deported from Bisbee is that they wish to return to their homes immediately, but they are aware that their arrival may cause acts similar to those of July 12th. We wish to avoid any breach of the peace, and so respectfully suggest that you incorporate in your report some method by which we will be enabled to return to our homes with adequate protection. We feel that we are not justified in longer accepting alms from the Federal Government so freely offered us in the situation forced upon the Government by the action of a lawless mob.”

And to Thos. Campbell, Acting Governor of Arizona: “On account of the troublesome times in the nation and the state, our men do not wish to be the means of causing any breach of the peace. We respectfully demand protection for return to our homes.”

To the Hon. Wm. B. Wilson, Secretary of Labor: “Will the Federal Government restore and make secure the constitutional rights of the men deported from Bisbee? Or does the Federal Government join hands with the state of Arizona in thus notifying the people of America that its common citizens have no rights worthy of consideration by men elected and sworn to uphold the constitution?”

And again, to the Secretary of Labor and the President: “Federal Constitution was violated when striking miners were deported from Bisbee. We are remaining here not because we want to be idle at Government expense, but because we believe that the Federal Government will return us to our homes and give us protection. Please say what the Government intends to do.”

After a few weeks the blankets issued to the deportees were withdrawn, and a notice was posted up in the camp, saying briefly that beginning on the morrow the food allowance would be cut down, and would continue to be reduced until at last nothing would be given. All telegraphic protests and queries about this brought no answer.

And so it was done, until the deportees were driven out of camp, to crawl home, without protection, the best way they could.

They telegraphed to the President, the Secretary of Labor, the Department of Justice, to Senator La Follette, Congressman Meyer London, Congresswoman Jeanette Rankin.

“The deportees intend to remain here insisting upon the restoration of their rights as citizens. If the Federal Government withdraws its support now the deportees will be in the same position as when the Government first came to their aid in Hermanas. Does a delay of two months nullify the rights guaranteed us by the Constitution? A definite answer is requested…”

To all these telegrams there were just three replies. Tumulty answered that the matter would be brought to the attention of the President; Jeanette Rankin answered encouragingly, and made a fight for the deportees; Meyer London was silent; but the bitterest irony of all was a letter from the Department of Justice in Washington:

“MR. A.S. EMBREE. SIR: September 29th, 1917. Your letter of the tenth inst. with reference to the deportation of yourself and other persons from the state of Arizona to Columbus, New Mexico, has been referred to this department, and the statements and arguments made by you therein have received careful consideration. This department does not believe, however, that there is any Federal law referred to by you which would justify action by the Department of Justice. Respectfully, For the Attorney General, WILLIAM C. FITTS, Asst. Attorney General.”

There is no law, then, which can be invoked to prevent the interstate deportation of workmen by private persons with guns! I believe that this letter will take its place in history beside that other great utterance of irresponsibility, “Let the people eat grass!”

I sat listening to a very simple fellow, an agricultural worker named Eggel, who was telling how the “vigilance committees and the gunmen from the towns of the Northwest hunted the I.W.W. farm-hands. Without emotion Eggel described how he and others were taken off a train at Aberdeen, South Dakota, and beaten up.

“One man would sit on your neck, and two men on your arms, and two on your legs, while a detective, Price I think was his name, beat us up with a 2-by-4, and it was criss-young crossed, notches made on it, this way and that way, so it would raise welts on a man…beat you over the back and your hips…

“So they took me away in one automobile, and they took Smith in another, and then they gave me another beating. So after that third beating I came back to Aberdeen, and slunk in at night, and I slept beneath a livery barn, and the next day I crept down to the depot and took a train for North Dakota…”

Listen to the scriptural simplicity of this:

“Well, they grabbed us. And the deputy says, ‘Are you a member of the I.W.W.?’ I says, ‘Yes’; so he asked for my card, and I gave it to him, and he tore it up. He tore the other cards up that the fellow-members along with. me had, so this fellow-member says, ‘There is no use tearing that card up, we can get duplicates.’ ‘Well,’ the deputy says, we can tear the duplicates up too.’

“And this fellow-worker says, he says, ‘Yes, but you can’t tear it out of my heart.’“

The humility of the workers is beautiful, the patience of the workers is almost infinite, and their gentleness miraculous. They still believe in constitutions, and the phrases of governments- yes, in spite of their preamble, the I.W.W. still have faith in the goodness of mankind, and the possibility of justice for the righteous.

Take care they do not lose this valuable quality. Take care, most arrogant master-class in the history of the world- call off your Vigilantes, and all of your hypocritical flim-flam which is invented in wartime to enslave the workers.

It will be an evil day for you if Tom Mooney hangs; it. will be an evil day for you if the I.W.W. goes to jail- singing in a deeper tone, as one of its young poets, M. Robbins Lampson, is singing:

“Justice became a harlot long ago

And sold herself to every master’s use.

Though some declare she died still pure,

I know She compromised with Death, and signed a truce

With Shame, who took her to his splendid house…”

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. An essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1918/07/v1n07-sep-1918-liberator-hr.pdf