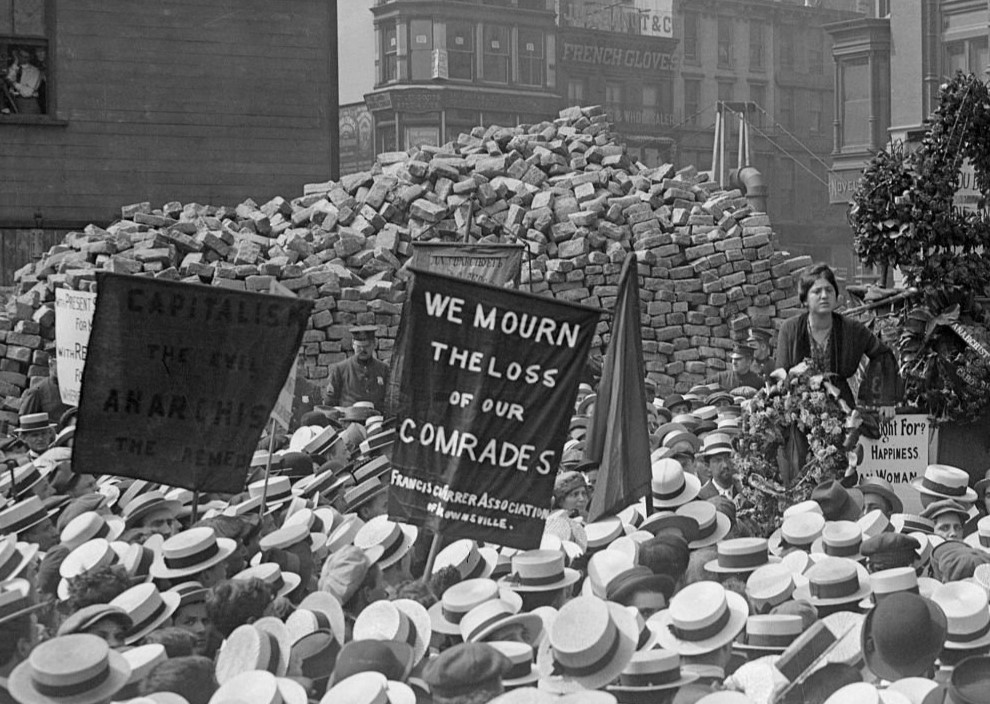

An important intervention by Elizabeth Gurley Flynn on the question of violence and defense of its oppressed perpetrators that divided the workers movement in 1914. On July 4, 1914 Quebec-born Arthur Caron along with fellow revolutionary anarchists Charles Berg and Carl Hanson were killed in an explosion at their 1626 Lexington Avenue apartment in New York City. Along with them, an uninvolved tenant, Marie Chavez, was also killed and twenty people were injured. Said to be a premature detonation of dynamite meant to assassinate John D. Rockefeller in retribution for the Ludlow Massacre of twenty strikers and their families, including 12 children, three months before, the event split the left with many, including in the I.W.W., of which the three were members or associates, distancing themselves in the aftermath.

‘Arthur Caron, “Dynamiter”’ by Elizabeth Gurley Flynn from Voice of the People (New Orleans). Vol. 3 No. 28. July 21, 1914.

On July 4th an explosion occurred in a tenement house on Lexington avenue in New York City. Four anarchists, three young men and one woman, were killed. Arthur Caron was the most prominent among them, having been actively identified with the unemployed, anti-militarist and recent free speech activities. Immediately lurid headlines in New York dailies attributed the explosion to bombs intended for Rockefeller and callous editors said “It served the ‘bomb-makers’ right.” But there is ample room for a reasonable doubt as to their responsibility. The police have “found,” as usual, literature, a printing press, apparatus, etc., but they have not been able to shake the statement of Louise Berger, the young woman who left her brother and the others asleep shortly before the catastrophe, that there were no explosives in her apartment. Nor have they been able to prove recent anarchist meetings anything more menacing than conferences with their lawyers as to their defense in Tarrytown. The possibility of some person bringing ex- plosives into the apartment, after the girl left, as e “plant” preparatory to a raid, is so apparent that even the New York Call, a paper certainly free from suspicion of anarchist sympathies, has suspended judgment. Clumsy and stupid as it may appear, there have been such plants before, and the animus of the New York detectives was manifest in their extreme brutality to Caron and O’Carroll during the unemployed agitation. Not only would such an “exposure of anarchy” prejudice the trials in Tarrytown and give ample excuse for rigorous suppression of all radical labor activities in New York City, but think of the glory for the Sherlock Holmes who would unearth the plot! It is a well known fact that men like Capt. Schaak or Bonfield of Chicago, Bimson of Paterson and Schmittberger of New York are anarchy-mad. They see a bomb in every red handkerchief. They attribute tremendous powers and fathomless depths of villainy to every young idealist who calls himself an “anarchist.” Men have been “framed-up” in New York innumerable times, revolvers dropped in their pockets, false witnesses hired, murders committed under cover of self-defense. It becomes the duty of all fair-minded people to demand a clear bill of particulars before accepting the police version of the tragedy.

Arthur Caron was a typical unemployed working man, not the “professionally unemployed” nor of the intellectual dilettanti so numerous during last winter’s agitation. He worked many years as a weaver in Fall River, but was interested in architecture and longed for a chance to study. He lost his wife and baby a short time ago. Grief and loneliness drove him to the “Mecca of America,” only to find thousands out of work, to tramp the streets hungry and cold and without success. Finally he drifted into Tannenbaum’s unemployed group, in the hope of some solution for his pressing problem. He was arrested in the church raid, arrested again with O’Carroll while going home after a meeting, thrown into an automobile and frightfully beaten by two detectives while two others held him. His nose was broken and he was sent to a hospital. Again in Tarrytown, where a meeting to protest against the Colorado outrages was attempted, he was hooted and jeered when he said: “I am an American,” and pelted with rocks and mud by the law-and-order element. He asked for bread. He received the blackjack. He asked to be heard. He received a volley of stones.

If this young man did turn to violence as the last resort, who is responsible? Who taught it to him? The psychology of violence is a very natural result of police brutality and mob lawlessness. This young man was denied any outlet for his protest against his misery, and left to brood over it. Couple with this a bitter indignation at the indifference of the latest Nero, who scattered Sunday school tracts while Ludlow burned, and his sufferings are evidence.

In the excitement following the tragedy one of the most exasperating features was the unseemly haste with which so many dilettanti immediately repudiated Caron. They never waited to give the dead the benefit of a doubt, found not a single extenuating circumstance. The anarchists were very fair in absolving the I.W.W. from any connection with their recent agitation. Joseph J. Cohen, secretary of the Ferrer Association, Alexander Berkman, Mrs. Sinclair stated Caron was not a member of our organization, in answer to the usual newspaper attempts to label every- one connected “I.W.W. To my mind this was quite sufficient. Since we were in no way involved I saw no reason why we should condemn or repudiate now any more than in the MacNamara case. But on July 6th the New York Call published the following from Joseph J. Ettor:

“The newspapers said this morning that Caron belonged to the I.W.W.,” said Ettor. “It is only fair to say that Caron was never one of us. When he tried to join the I.W.W. we refused to let him in for excellent reasons, one of which was that he didn’t work.

“The I.W.W. doesn’t approve of dynamiting or setting off bombs or taking human life. We have been accused of violence, but that is not true. The I.W.W. has neither advocated nor participated in violence against social order. General strikes is the method we favor for overthrowing the capitalist system, and that is the only kind of force we are in favor of. “Caron took part in several of the demonstrations in this city and elsewhere, but he acted as an individual in some, and others were not I.W.W. demonstrations at all. Everybody is trying to make the I.W.W. the goat.”

On the 8th, in reply to a critic, he repeated this in substance except to admit that the I.W.W. believed in violence “as a defensive measure,” and to state that a committee of Local No. 179 were authority for the statements about Caron’s rejection.

I see no reason why the committee could not speak for themselves, but I emphatically take issue with the sentiments expressed both by them and Fellow-worker Ettor.

I do not think they express the opinions of the general membership and it brings to an issue two propositions:

1. Does unemployment constitute a bar to membership?

and

2. Who does speak officially for the I.W.W. on its attitude towards violence, or should anyone so speak? It comes with poor grace from Local No. 179, of which I am a member, to reject a man because he was unemployed, when in this very much “mixed” local there is a capitalist, a rich doctor employed by the city, a minister of the “Church of the Social Revolution,” several school teachers, and more than several persons who haven’t worked for a very long time. Just why was Caron ineligible? Does the fact that he “was not working” constitute a bar, as Ettor says? I have never so read in the I.W.W. Constitution. If a weaver, unemployed, applied for membership in Local No. 20, Lawrence; Local No. 152, Paterson; Local No. 157, New Bedford, do you suppose the secretary would refuse his application? The qualification for membership is “an actual wage-worker” (it doesn’t say employed or unemployed), one who accepts the concept of the class struggle and believes an economic industrial organization is necessary for immediate betterment and ultimate emancipation. A workingman may be an anarchist or a socialist, a Catholic or a Protestant, a Republican or a Democrat, but subscribing to the preamble of the I.W.W. he is eligible for membership. And we are not responsible for his individual views or activities, be it the confession of the Catholic, as in Lawrence; the ballot of the Socialist, as in Paterson; the Republican agitation among the Italians of New York who took the flags away from the monarchists by force and still retain them, or the anti-Rockefeller demonstrations participated in by some of our New York members. So long as the individual performs his duties as a loyal member of the union, his personal affairs remain inviolate.

Caron’s desire to join the I.W.W. was probably a result of his experience as a textile worker, plus his contact with the I.W.W. men, who initiated the unemployed movement at Fellow-worker Haywood’s suggestion. It had a twofold purpose, to stimulate those out of work to action on their own behalf, and to popularize the eight-hour program as some amelioration for unemployment. Naturally anyone who showed intelligence and ability, our fellow-workers looked upon as good material for the I.W.W. After Tannenbaum, Plunkett and the others were arrested, the movement began to drift aimlessly. Tresca, Hamilton and I argued that the I.W.W. should take the helm actively, but were overruled, so that while our organization had full responsibility it had no control. Then it was that the anarchists came in and assumed the leadership, which they had a right to do under the circumstances.

Eventually our men realized that if they were to have the name they must have the game, so they organized what they called for expediency “Local No. 1 Unemployed I.W.W.” This was at Haywood’s suggestion and while it was not officially a component part of the I.W.W. the plan was to issue cards that would be honored as a transfer when the men had work and money to pay dues in the local of their industry. Its program to hold meetings advocating the I.W.W., especially along the water front, was very practical, as the unemployed movement was petering out. The secretary of this was Charles Plunkett, a member of No. 179, and Caron was one of the members enrolled.

During the interval between Tannenbaum’s arrest and the formation of this Local No. 1, everyone who bobbed up was labeled I.W.W., “red virgins, white virgins, sweet Maries,” etc. It may be contended that the men had no right to organize this Local No. 1, but if they couldn’t get new recruits into No. 179, how were they to hold them together? It impressed them as most reasonable way to gather some fruits for their labors, and was in spirit the I.W.W. Possibly a great deal of confusion could have been cleared up in the minds of the workers if Ettor had spoken at the final Union Square unemployed meeting. Haywood and I were both sick, but Ettor, who was in the crowd, refused to speak, and the I.W.W. propaganda lost a valuable opportunity, but received credit for a lot of nonsense.

After the I.W.W. initiated the unemployed movement in New York City it is almost an admission that we did so to capitalize misery, to refuse a man a membership card because “he was not employed,” and I have emphasized this not to defend Caron, but to exonerate ourselves from any such suspicion. We all heartily endorsed Fellow-worker Haywood’s suggestions, because we understood the primary motive was to arouse the unemployed to demand jobs or bread; the secondary motive, to make them realize that the I.W.W. is the only organization offering an adequate program to abolish the system that makes unemployment inevitable.

Without for one moment impugning his sincerity, I believe Fellow-worker Ettor is entirely too diplomatic in his attempts to make the I.W.W. pacifically palatable. The clarity of St. John’s statement before the “United States Industrial Relations Commission” was destroyed by Ettor’s subsequent explanations, although he had not heard St. John’s testimony.

What is the final word for the I.W.W. on the subject of violence? Is it Ettor’s that “the general strike is the only method we favor for overthrowing the capitalist system and that is the only kind of force we are in favor of?” Was it St. John’s before the Industrial Commission, that violence would be used if necessary to accomplish a social revolution, without regard for life or property? Is it embodied in Haywood’s and Ettor’s article on the I.W.W. in the New York World of Sunday, June 14th: “The Industrial Workers of the World have been accused of violence. This is not true. The I.W.W. have neither advocated nor participated in violence against the social order?” Or did Lessig speak correctly, when he answered the question of the stand on violence by saying: “We might hesitate at first to advocate it, but if we saw fit I guess we would?”

St. John has said in “The History of the I.W.W.”: “The tactics used are determined solely by the power of the organization to make good in their use,” and instances the “taming” of the Cossacks in McKee’s Rocks.

Giovannitti had an article in The Independent of October 13, 1913, on “Syndicalism, the Creed of Force,” in which he says:

“UNMORAL VIOLENCE.

“It is not true that it is unconditionally opposed to political action in the generally accepted sense of the word, and it is equally false that it is opposed to the use of physical force. As a matter of fact, if Syndicalism does not openly advocate violence, as some anarchists do, it is neither because of a moral predisposition against it, nor on account of fear, but simply because, having a vaster and more complex conception of the class war, it refuses to believe in the myth of any single omnipotent method of action. Violence. moreover, being the extreme outward expression of a moral reaction created by outside situations, is objective and instinctive and not subjective and artificial.

The law of the least effort will unconsciously but firmly induce the workers to refrain from violence, but if impellent needs and the inflexible necessity of getting certain results make it indispensably condition- al to the solution of a deadlocked controversy, it will of course automatically assert itself, even without an expressed suggestion. In this case, being neither counseled nor premeditated, violence is neither right nor wrong-it is either necessary or unnecessary, effective or useless, as the resulting circumstances alone will determine.”

Now, where do the rest of us stand? Is the position of St. John, Lessig and Giovannitti universally accepted by the I.W.W. or is Ettor’s? Granted that there is no “official” position, no Article A, Section B in the constitution, about this, still there should be some approximate agreement or else each one should distinctly state “this is my personal opinion” and cease saddling the organization with it, be he pro or con.

As a matter of fact, I believe Giovannitti has stated what most of us think, and St. John’s utilitarian position needed no amplification. But whichever version we take, let us have some uniformity, that we may never again witness the absurd spectacle of the General Secretary saying, “This is the I.W.W. position,” only to be contradicted by a national organizer in a little while! This does not mean we should bind ourselves to an endorsement of violence, nor does it mean we should repudiate it per se. Either to my mind would be equally unwise and dogmatic. “Circumstances alone will determine,” impresses me as the most common sense attitude. Certainly the most conservative of Socialists would justify the offensive as well as defensive action of the miners after the Ludlow massacre.

But whether we do or we do not accept violence, there can be no reason why after refusing to condemn the MacNamaras who pleaded guilty we should now spit on the mangled corpses of dead workingmen, whose lips are stilled and who may be the victims of a gigantic conspiracy. We need not accept their ideas, we need not take the responsibility for their words or deeds; yet if we believe them guilty we may extend to them sympathy for their intense suffering that found an outlet only in this desperate futile way; sympathy for their horrible deaths; sympathy for the foolish shortsightedness that carried explosives into a crowded tenement house. We may realize that violence against an individual will not change conditions. nor will revenge restore the babies of Colorado. But let us fix our condemnation on the brutality that produced such a psychology, a hate as quenchless as our wrongs; on the society that drives her children to such desperate retaliation.

Surely we are big enough in spirit and bold enough in character to inscribe on our banner: “The working class, may they ever be right, But right or wrong-the working class!”

The Voice of the People continued The Lumberjack. The Lumberjack began in January 1913 as the weekly voice of the Brotherhood of Timber Workers strike in Merryville, Louisiana. Published by the Southern District of the National Industrial Union of Forest and Lumber Workers, affiliated with the Industrial Workers of the World, the weekly paper was edited by Covington Hall of the Socialist Party in New Orleans. In July, 1913 the name was changed to Voice of the People and the printing home briefly moved to Portland, Oregon. It ran until late 1914.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/lumberjack/140721-voiceofthepeople-v3n28w080.pdf