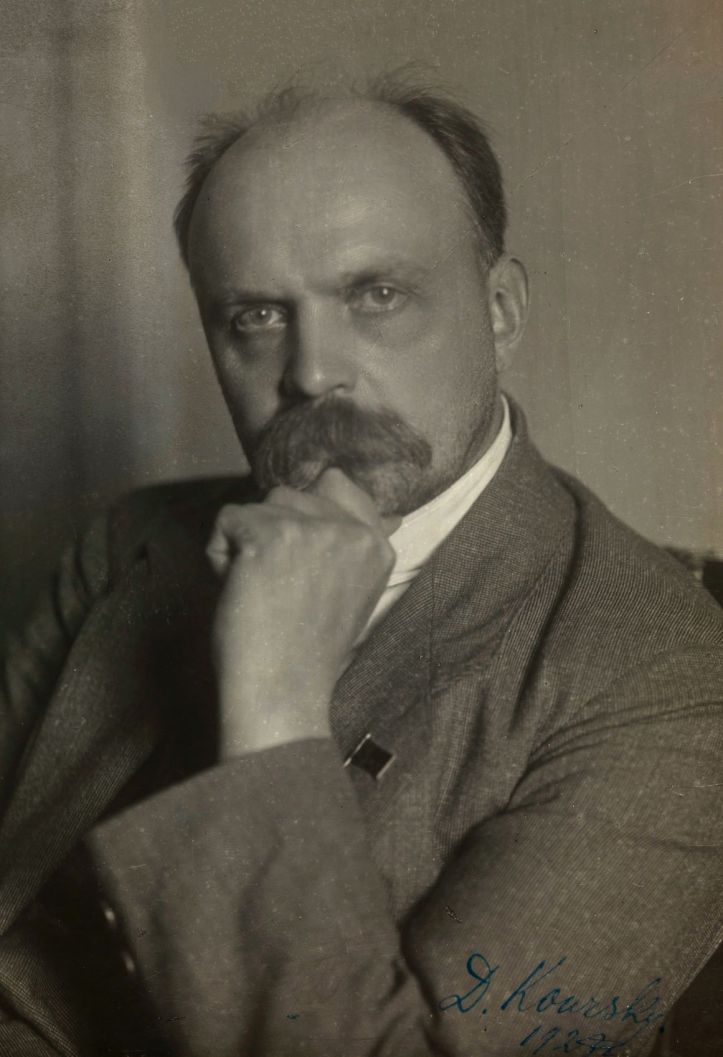

Dmitry Kursky was instrumental in creating the early Soviet legal system as Peoples Commissar of Justice from 1918 until 1928. Here he gives an early overview of law under the Soviet state.

‘Three Years of Proletarian Law’ by Dmitry Kursky from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 4 No. 17. April 23, 1921.

(The author of the extremely interesting account of “Two Years’ of Proletarian Law” in the Soviet Government’s Handbook to commemorate the Second Anniversary of its foundation, herewith brings his observations up to date.)

“Social Life is in its essence of practical nature.” This Marxian sentence finds its best support in the labor that has been performed by the proletariat in the field of law in the course of these three years. After the proletariat had repealed the old legislation and abolished the pre-revolutionary national institutions, particularly the old courts, it was afforded an opportunity for the construction of the new order and thus was enabled from the very outset to enter the path of practical realization of new forms of social life adapted to its nature.

By creating a state whose legislative and judicial branches consisted only of workers and were elected by the workers, the proletariat enabled its institutions to function without first having achieved complete perfection of the whole proletarian system, and to operate in the direction of further and further developing and perfecting the laws in accordance with the interests of the proletariat. And now, at the threshold of the fourth year of the Revolution, the proletariat is able to create a number of codes, in other words, books of law based on a unified basis and constructed in a systematic manner, embracing the national structure, the organization of labor, the organization of national economy, and penal code protecting these institutions. This work has been practically undertaken by the People’s Commissariat of Justice. But already now it may be said that the proletariat will assign to the code of laws created by it that place which appropriately belongs to a code of laws in a proletarian state: the code will not become a time-honored, century-old code like that of the bourgeoisie, such as for instance the Code Civil (Code Napoleon), but will be primarily a systematic book of reference for the administration and the courts in their daily work, and only for the duration of the transition period until the proletariat shall have eliminated class rule and with it the state itself. This practical character of proletarian justice and of its organs may be traced through the course of the last three years; the substance of the law, in its perfected forms, in other words the code, as well as the organs of law themselves have passed through a constant transformation. Typical illustrations of this transformation are: 1) the organic law (Constitution of the R.S.F.S.R.) of 1918, was supplemented and partly amended as far back as 1919, particularly in the matter of the relation between the central and local authorities by the acts of the 7th Soviet Congress and still further in the next year by a regulation of the Central Executive Committee on volost and uyezd Soviets; and this process of amending the Constitution is unceasing, for just at this moment a Commission is elaborating the norms of the relation between the People’s Commissariats and the Executive Committees; (2) the code of the R.S.F.S.R. on civil law, passed by the Central Executive Committee in 1918, was amended by a number of subsequent decrees concerning the bringing up of minors as well as social welfare work for older children; it is to be replaced by a new code now being drawn up by the People’s Commissariat of Justice; (3) the code of labor laws of 1918 has been essentially amended and enlarged, both by the decrees on labor duty, as well as by the wage scale regulations of 1920; (4) during these three years five decrees on courts have been issued, which to be sure do not touch the foundations of court organization—collegium courts and relief judges—but offer in each case a great number of new norms, for instance a new procedure for preliminary examination and defence, in the provisions of 1920; (5) in three years ten decrees on revolutionary tribunals have been promulgated; thus in 1920 detailed regulations on — railway military tribunals appeared. Such examples may be cited in every field of the national administration. One might point out also the reasons for and the nature of the amendments, but it is at present important to state only one thing: the legislation of the Soviet Government is of very practical character, and, unlike the aloof and distant bourgeois laws, does not lag behind life, but uninterruptedly undergoes a process of amendment parallel with the development of the proletarian state. The following figures will show the increasing participation of the working class in legal institutions as well as in the people’s courts:

Number of: 1918 1919 1920

People’s Courts: 2887 2942 3708

Revolutionary Tribunals: 37 39 51

If one recalls that each people’s court in the course of a year requires at least one hundred judges (relieving each other in succession), we shall see that in the last year as many as 1,500,000 workers have directly participated in the court business, notwithstanding the fact that the whole court apparatus is only one fifth as large as that of the pre-revolutionary period. The people’s courts in 1920, according to the figures for twenty six provinces, disposed of 708,000 cases, criminal cases constituting about sixty five per cent of the whole number. The activity of the people’s court is best characterized by the nature of the punishments imposed. In the first quarter of the year 1920 there were sentenced: to deprivation of liberty 29,586 persons (11,580 of this number to suspended sentences); to public labor without loss of liberty, 13,201; to fines 36,150; to public censure, 5,618; to other punishments, 6,403 persons.

These figures sharply distinguish the people’s courts from those of the pre-revolutionary era: sentenced to work without loss of liberty, suspended sentences, and public censure—these punishments, applied on a large scale, did not exist under the old laws; they were recommended for adoption to be sure by social criminologists (for instance suspended sentences). The division “other punishments” deserves still greater attention: under this head it has frequently happened that the courts have created types of law that are new in the fullest sense of the word. Thus, for instance, people’s courts would sentence persons for counterrevolutionary comments or for anti-political expressions of opinion, to conditional punishment requiring the offender to present to the court before a certain date a certificate of attendance of a course in political science; or, in order to honor the reputation of the revolutionists who died heroically, those offending their memory are required to decorate their graves with flowers; in combating such practices as neglect of duty or exploiting the masses by means of religious prejudices, trials were held with the greatest possible publicity, since the sentences and the opinions in support of them constitute extremely useful material for political propaganda, etc.

Such is the activity of the people’s courts. This activity shows that the proletariat is creating ever new forms of social life also in the field of law not merely taking revenge on the criminal, but with the object of adapting the human material that is available, inherited from capitalism as it is, to the new modes of life leading to Communism.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v4-5-soviet-russia%20Jan-Dec%201921.pdf