‘The Death of Durruti’ from Spanish Revolution (United Libertarian Organizations New York). Vol. 1 No 7. December 9, 1936.

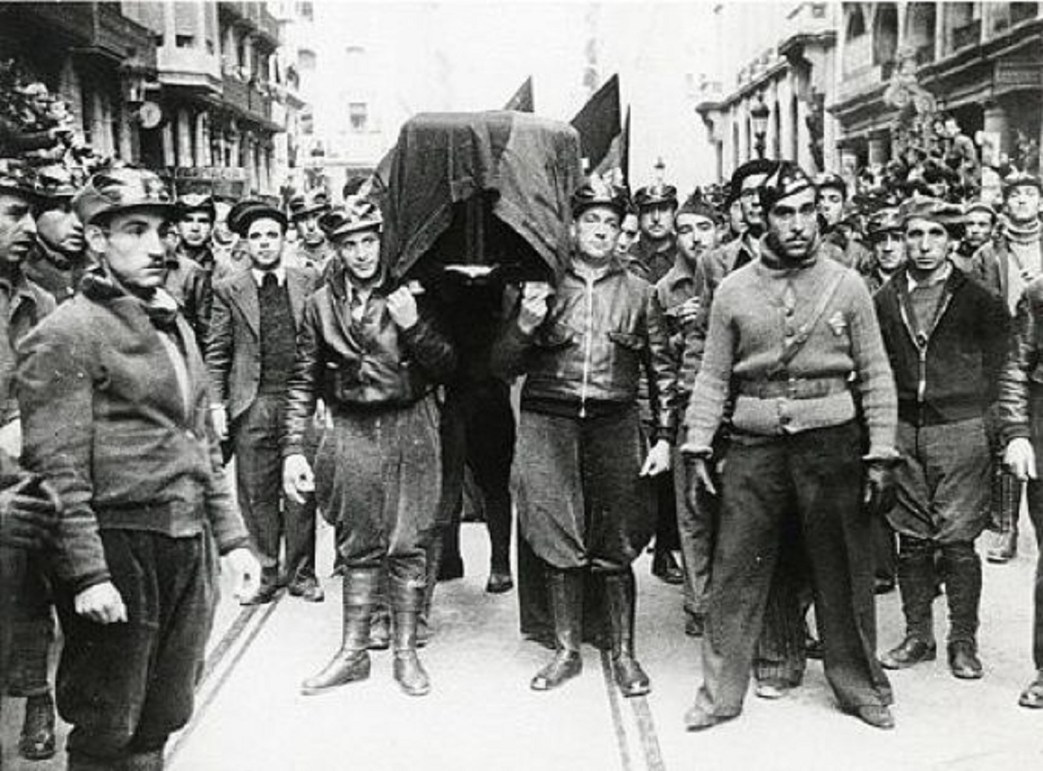

Five hundred thousand people marched to the grave of Buenaventura Durruti. They did not goosestep in military-like formations as the drilled and robotized crowds of dictator-ridden countries do. They marched in the spontaneous fashion of revolutionary crowds, swept by the deep feeling of grief for a lost revolutionary hero. It was a spontaneous outpouring, a spontaneous manifestation of popular sympathies, of a deep-felt sense of reverence for one who in his life and actions came to embody so much of the hopes and aspirations of the toiling masses of Spain.

He was a revolutionary hero and not a “professional” revolutionist of the kind which did so much to discredit the idea of revolutionary action in the eyes of the working masses of the world. He did not divorce moral responsibility from revolutionary action. His heroic life was impelled by a sense of revolutionary duty, freely accepted and acted upon in the manner of a free individual. He did not stultify himself before a “Leader,” did not glorify the soulless discipline of a revolutionary automaton.

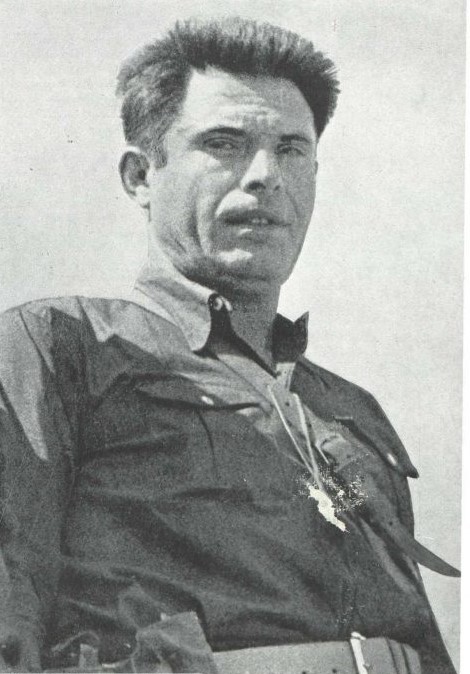

Hence the great power welling from the innermost being of this man who only four months ago was still working at his factory bench. It is the same power which now emanates from the great mass of revolutionary workers of Catalonia, enabling them to perform the miracles of revolutionary reconstruction so much admired by every observer. The revolutionary masses of Catalonia responded so readily to the magnetic force of an idealist revolutionary like Buenaventura Durruti, because they felt him to be one of them, a man who came to represent somewhat more vividly the heroic qualities of a class that is aware of the creative stirrings of a new world.

And because Durruti’s life was imbued with that sense of individual moral responsibility, the sense of spontaneous solidarity, the revolutionary passion of a libertarian, it is because of this fact he succeeded in inscribing by his epic life and death one of the most glorious pages in the heroic struggles of the Spanish proletariat. From his youngest days he served the revolutionary cause with the modesty and unobtrusiveness of a true revolutionist. He did not fight for leadership, for superior commanding positions. There were none in the anarchist movement which he embraced so fervently. He fought alongside the workers of Barcelona in the darkest hours of the Fascist dictatorship of Primo De Rivera. It was then that his name already became a legend to the great mass of Barcelona workers, who, unlike the drilled and disciplined workers of the Marxist countries, did not resign themselves meekly to the Fascist dictatorship. He fought the Fascists with their own weapon. The acts of Fascist terror were not let go unanswered. Untrammeled by pedantic “revolutionary” theories, by a brain-spun strategy derived from holy texts and writings, he reverted to individual terror, which in the time of complete Fascist domination, kept the fire of revolutionary enthusiasm burning among the masses of workers.

He tasted to the bitter end the life of a revolutionary hounded at home and in exile. Driven from one country to an other, persecuted by the police of almost every “democratic” country of the world, he kept on wandering from one refuge to another, leading the tortured life of an anarchist exile.

He went back to Barcelona immediately after the revolution of 1931. He could easily have compensated himself for the years of suffering by some soft political job which were open at that time to every expatriated exile. But like many of those comrades who made the anarchist movement the great moral power it is now in the life of the Revolution, Durruti spurned any offers of that kind. He went to work in the factory, and it is from there that his clarion call for a new real revolution resounded throughout the whole country. While working at the factory bench, he became a greater power than the socialist politicians occupying prominent ministerial positions.

He was the first to raise the banner of revolt against the sham of the new democratic government. He exhorted the workers to bestir themselves to a new mighty effort toward a genuine revolution and not the kind of which the politicians spoke in 1931. And because of his tremendous influence, he was singled out for persecutions by the new governing powers. He was banished to Africa, beaten and tortured in the prisons, hounded at his place of work and driven from one factory to an other.

But around him the steel wall of proletarian solidarity kept growing in strength and power of resistance. In spite of all the persecutions and machinations of the government, the workers of Barcelona flocked to the banner of social revolution raised by Durruti and his comrades of the anarchist federation. It was due to Durruti and thousands like him, nameless heroes of a great movement, that the workers of Barcelona were not caught mapping in the great critical hour of the Fascist revolt. Together with other countless heroes, Durruti fought at the barricades of Barcelona where the destinies of the Spanish revolution and that of the fate of the international proletariat hung in the balance.

And then from the street barricades of Barcelona to the most dangerous sector of the front, leading one of the most valiant brigades of comrades, which already made history by saving Madrid in its critical hour. The “General” Durruti- that is what the capitalist and communist press wrote of him. But he was no more a “general” in their sense than he was a “Leader” of the Stalin kind. He led his men by the power of personal example, of moral persuasion, of revolutionary enthusiasm and deep faith in the cause of the common man that permeated his being. He demanded discipline, but the free self-control of a class-conscious revolutionist, and not the drilled automatic obedience insisted upon by the socialists and communists in their attempt to shape the fighting forces of the Revolution in the pattern of the Russian army. And now even the enemies have to recognize that his brigade was one of the best fighting units in the military sense.

His death came as a fitting climax to his heroic life. Always in the front ranks of his fighting men, sharing the risks and hardships of every comrade in his brigade, he finally succumbed to the numerous wounds received during the fight for Madrid. Always fighting shoulder to shoulder with the masses of workers battling for a new humanity, exercising leadership by personal example and revolutionary action displayed on a high moral plane such he remained to his last minute. And in revering him the great masses of workers that poured out spontaneously to pay hommage to his epic life and death, also paid a deep felt tribute to the libertarian movement which molded and shaped the heroic qualities of this man into the pattern of a new humanity.

Spanish Revolution (not to be confused with the POUM supporters’ paper of the same name, time, and look) was the English-language twice monthly journal of the United Libertarian Organizations (ULO) from 1936 until 1938. The paper was initiated by Spanish C.N.T. delegates in New York City to support the anti-fascist revolutionary syndicalists of Spain. Editorship was collective, with the ULO including the Jewish Anarchist Federation (Freie Arbeiter Stimme), the Russian Federation (Dielo Trouda), the Vanguard group, several IWW locals, a Spanish language federation (Cultura Proletaria), and Carlo Tresca’s Il Martello.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/spain/spanishrevolution/v1n07-dec-09-1936-span-rev-nyc.pdf