A substantial look back by Clara Zetkin in this essay written for the tenth anniversary.

‘Effect of the Russian Revolution of 1905 on the West-European Labour Movement’ by Clara Zelkin from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 5 No. 76. October 26, 1925.

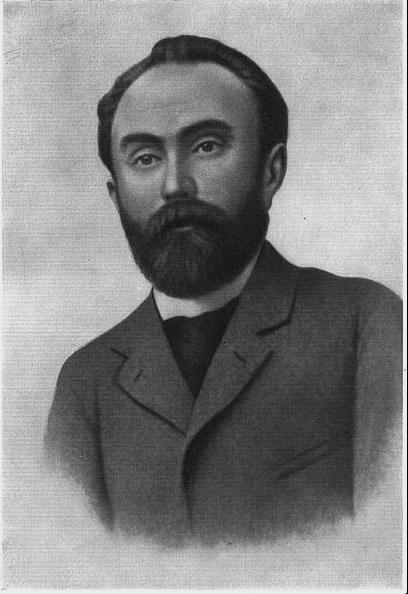

“You should not have taken up arms”. This was the priggish hectoring message which Plekhanov sent to the heroic champions of the Russian Revolution after the December events of 1905. This appreciation reminds one strangely of Vollmar’s notorious statement at the Stuttgart Party Congress of the Girman Social Democratic Party in 1898: “The Paris workers and lower middle class would have done better to go to bed than to set up the Commune.” The same Vollmar spoke quite differently in the Autumn of 1882 when he was in the full bloom of his “radical” sinfulness. In a lecture on the Commune of 1871 at the German Social Democratic Club in Zurich he showered praises on “the bold and unprecedented rising of the Paris workers”. In criticising the various practical errors and weaknesses of the Communards he claimed under the thunderous applause of his audience: “One should have made quite a different use of the guillotine than to turn it as was done in a sentimental theatrical scene.” The striking difference between these two historical appreciations of the Commune, is a glaring illustration of Vollmar’s transformation from a “radical” into a revisionist.

The witty Marxist, Plekhanov would have no doubt denied most energetically the assertion that in the appreciation of great revolutionary events he stood on the same level as the champion and leader of an anti-Marxist, lacking in faith, acquiescing in opportunism. However, without having the least intention to place the personality of Plekhanov on the same level as Vollmar, one cannot deny that there is a strange kinship in both their attitudes to a defeated revolution. Confronted with the defeat of the revolutionary forces, both of them lost the power to make a correct appreciation of the world events, a power which enables people to look with confidence to the future and to victories of tomorrow in the non-success of today. The tangible result of the moment prevented them from appreciating correctly the irresistible driving force of revolutionary eruptions, the outcome of social conditions and their importance for the further development of society. It also prevented them from understanding the continuous creative power of such eruptions. The great historical significance, the challenging fertility of revolutionary mass initiative was lost to them. Plekhanov’s judgement of the revolution of 1905 foreshadowed his later development, that is more: it contained as in a nutshell the conception which led to the decline of the Menshevik party, to their betrayal of the October revolution of 1917.

Lenin, who had derived from the thorough study of history a great understanding of the substance of revolution, saw with his keen appreciation of facts and of any possibilities for development the danger lurking in Plekhanov’s attitude to the revolution of 1905 for the strong and purposeful policy of the party, which wanted to be and could be the leader of the masses in future revolutionary struggles. For he was fully aware of the enormous and unique importance of revolutionary mass initiative as a factor in history. He therefore opposed Plekhanov’s condemnatory opinion with his usual determination and power. “You should not have taken up arms”. This judgment was tantamount to ignoring and denying the importance of mass initiative at a time “when Russia was going through a formidable revolutionary change.” Lenin’s “Introduction” to Karl Marx’s “Letters to Kugelmann” dated February 5, 1907 is a panegyric of “the historical initiative of the masses” which, like Marx in his appreciation of the Commune “he placed above everything else.”

“Oh, if with respect to the appreciation of the historical initiative of the Russian workers and peasants in October and December 1905 our Russian Social Democrats would only learn from Marx”, Lenin exclaimed and he added on the strength of the letters: “In September 1870 Marx called the rising madness. But when the masses rose Marx wants to march with them, to learn himself in the struggle together with them, and not to preach at them. He understands that any attempt to give a definite prognosis of the chances would be either charlatanism or hopeless pedantry. He put before everything the fact that the working class is making world history heroically, resourcefully and with self-sacrifice…Marx could even recognise that there are moments in history when a desperate struggle of the masses even for a hopeless cause is necessary for the further education of the mass and their preparation for the next struggle.” Lenin urges “to learn from the theorist and leader of the proletariat to believe in the revolution, to learn how to rouse the working class to defend itself until the aim of their revolutionary tasks has been achieved, to learn to preserve the will to power which does not tolerate pusillanimous despair because of the temporary non-success of the revolution.”

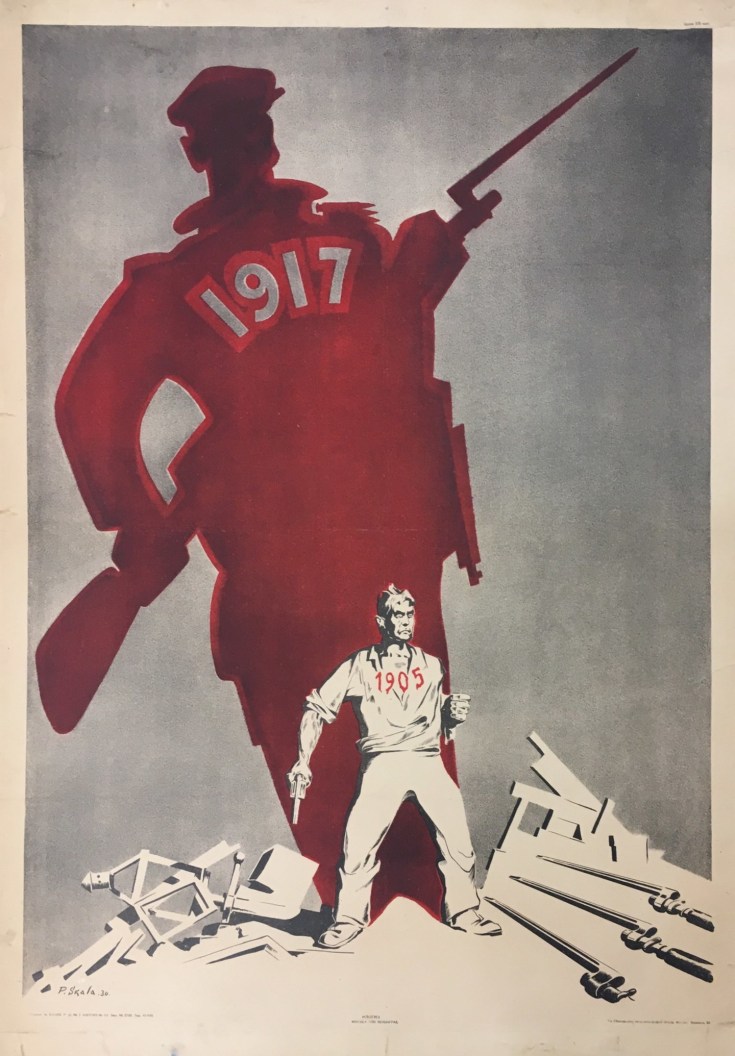

The proud and prophetic words with which Lenin concluded his “Introduction” have become reality: “The Russian working class has already shown once and will show again and again that it is capable to storm the heavens.” The Russian working class has stormed the heavens. That its storming was translated into victory is the result of Lenin’s life work. Guided by the clear recognition of the revolutionary character of the time and of the situation in Russia, inspired by the unshakable belief in the revolutionising power of mass initiative, he worked with iron logic and unflagging energy at the creation of the party, which armed with the right spirit, determination and organisation, acquired the capacity to raise volcanic mass initiative to purposeful revolutionary mass determination, and to be the brain, the back-bone and the guiding hand of revolutionary mass struggles. A solid double chain consisting of strongly welded together links connects the working and peasant masses who fought and suffered a glorious def at in the revolution of 1905, and the Bolsheviks who fought and learnt with them, the victorious proletariat and peasantry of the Red October of 1917 and their leading class party. But the creative spirit awakened by the defeated revolution made itself felt in the international labour movement at an earlier date than in Russia.

The hankering of the highly developed industrial states after a “place in the sun”, the war made by Japan against China and by the U.S.A. on Spain, the Boer War, the campaign of the great Powers against China under Wilhelm’s leadership, who bragged beforehand about the laurels which were to be reaped, the Russo-Japanese struggle for supremacy, all this showed that capitalism had entered upon the era of imperialism. The differences between the great capitalist states increased in number and became more acute. These differences were fraught with the danger of sanguinary contests of arms on a large scale, of terrible destruction in which the proletariat could not consent to play the role of gladiators if they were intent on looking after their class interests and the social differences within the capitalist states had also grown and become more acute. The formidable gulf between exploiters and exploited has been widened. The bourgeois mode of living of the small labour aristocracy and of its political and trade union bureaucracy could not eradicate the fact that large sections of the proletariat vegetated not only relatively but absolutely in want and misery and frequently went under. The fact that the proletariat had organised itself certainly increased its economic and political power, enabling it to defend itself against exploitation and enslavement. But at the other pole of society the economic and political power of the bourgeoisie had grown tremendously. The fighting methods and weapons hitherto used by the proletariat proved to be more and more ineffective against the deadly enemy of the workers. The fruit reaped from the nothing-but-trade union movement and from the parliamentarism was sour and far from plentiful, even where the bourgeois rule was a democratic rule.

The cry for bread, justice and liberty of the starving masses demanded as insistently as the theoretical perspicacity in the left wing of the Second International, new means and methods for the proletarian class struggle. The important role of the proletariat in the process of capitalist production pointed forcibly to the general strike, the political mass strike as an adequate weapon for the proletarian struggle. Herwegh’s “Bundeslied” sung by ever-growing proletarian masses in which he called on the masses to awaken and realise their power to hold up the wheels of fate was a challenge to the bourgeois world.

The recognition, or rather the application of the mass strike, was for a long time the subject of heated discussion within the Second International. At first there was not a “clean cut” division in the pros and cons, between reformists and revolutionary Marxists. A good few who claimed for parliamentarism the monopoly of all means of grace and the power to lead the proletariat along paths strewn with flowers to victory, were for the mass strike as a means for the defence or conquest of a democratic franchise. Their championship of the mass strike was certainly half-hearted, for if not consciously, at least instinctively the chieftains of opportunism and revisionism in the Second International felt the revolutionary, historical substance and the revolutionising effects of the general strike.

This contentious question had not yet been settled in theory by the Second International even as an expression in a pious resolution, when the mass strike confronted it challengingly in practice. The cause of it was the struggle of the Belgian proletariat for universal suffrage and the secret ballot. This struggle brought to light the self-sacrificing determination of revolutionary mass initiative and also the incapacity, weakness and treachery of the leading Vanderveldes. The spontaneous general rising of the mine slaves was called off in favour of parliamentary action, which on its part did not even make full use of the powers of parliamentarism, and ended shamefully by a whining letter to the royal “friend” of the dancer Cleo de Merode. The self-sacrificing mass strike in Holland was also not allowed to be brought to a successful issue.

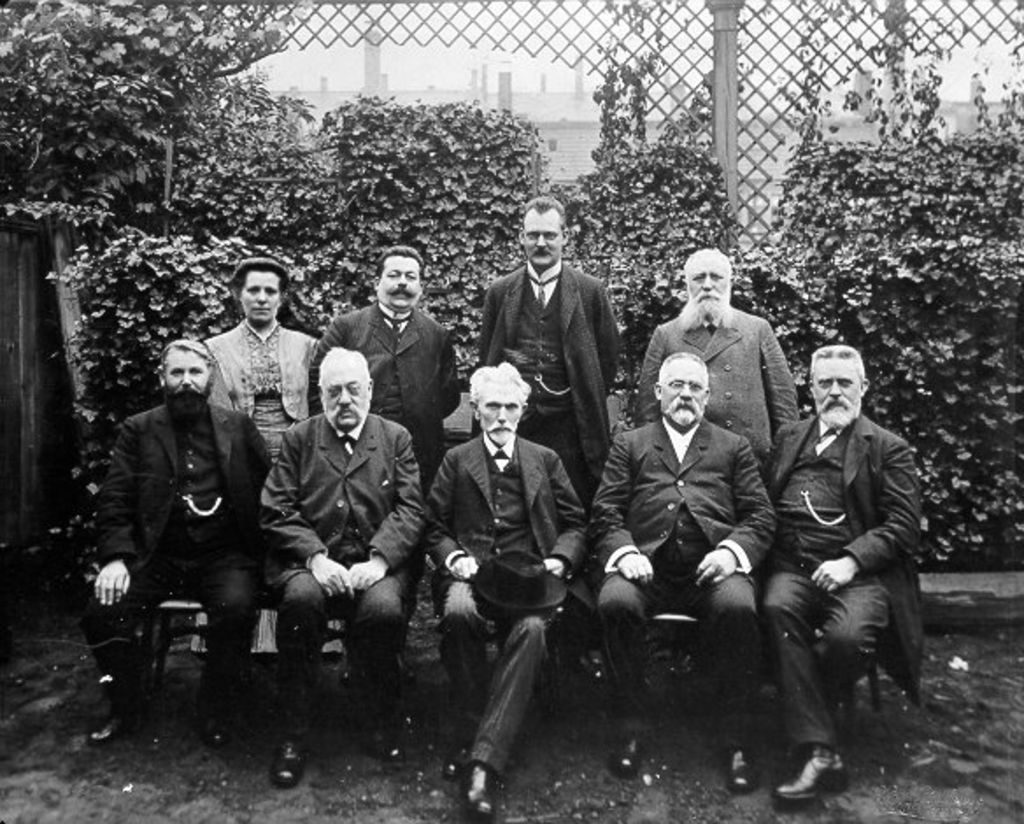

Nevertheless the general strike remained on the agenda of history, for both these cases threw only light on the difficulties and perils of its application, but did not by any means prove its inadequacy as a weapon of the proletariat. The leaders of the Second International were compelled to place it on the agenda of the World Congress in Amsterdam in 1904 together with the question of ministerialism which kept the Social Democratic Parties on edge, in spite of the Paris compromise resolution or rather because of this accursed resolution. The great battle which raged around ministerialism for which Jaures fought with all his genius, power and brilliancy, relegated the interest in the general strike to a back seat. Among its most obstinate and impassionate champions was Aristide Briand who subsequently showed himself more able than the Sheidemanns and Eberts to make full use of a business coalition with the bourgeoisie. Just as in the question of ministerialism so in the question of the general strike one of those “unanimous” decisions was concocted which left in the end the matter undecided and gave in fact no satisfaction either to reformists or revolutionary Marxists. It is true the political mass strike, as a proletarian weapon, received the official blessing of the Second International. But its application was connected with so many reservations and was made dependent on so many precautions and considerations before and after that it was tantamount to a postponement till doomsday. The Congress of the German reformist trade unions held in Cologne in 1905 drew the practical conclusion from the Amsterdam decision. Under the influence of artful opportunist wire-pullers and dominated by the fears of shortsighted trembling bureaucrats, the Congress forbade propaganda of the political mass strike and absolved the trade unions from any obligation to support it.

The thick, stifling, paralysing atmosphere of those years was rent by the voice of the Russian Revolution: “I am”. A voice which roused the masses and brought clarity and determination to the revolutionary Marxists in the Second International. Revolutionary mass initiative made itself powerfully felt in Russia. It made “world history” by mass strikes of various professional groups which sprang up like hot springs. It sent forth from the barricades deadly lead into the ranks of the enemy. The electrical spark of the revolutionary mass rising flew across the frontiers of Russian. The first most direct and powerful effect of the revolutionary struggles in Russia and Russian Poland on the proletarian masses was stunning, but soon there was joy at the fact that workers and peasants had taken up arms to fight for their freedom. For had not even good radical Marxists taught that through the technical development of firearms, modern town planning, etc., street and barricade fighting had become impossible and belonged so to speak to a stone age of revolutionary exposition. Engels’ foreword to Marx’s “Class Struggles in France”, or rather its misinterpretation by the Party Committee had led them astray. But low and behold barricades which seemed to have grown out of the earth, rifle fire and the thunder of cannon proclaimed that the exploited workers can defend themselves with arms against their masters and tormentors. This recognition gave an impetus to the feeling of power and the proletarian masses gained therefrom determination to fight and to attack. The superstitious belief in “lawfulness”, “normal, peaceful development” and in the “gradual growing into Socialism” received a severe blow. The role of armed struggle, of mass power as an inevitable, revolutionary, historical factor was felt instinctively or in some cases realised consciously. “To want to speak Russian” with the exploiting and enslaving authorities was already then a quite usual form of speech at workers’ meetings. The effect of the Russian Revolution did not evaporate in high-flown sentiment. It brought forth results. This was the case first of all and above all, wherever the masses were near to the revolutionary fighting centre and wherever the mass rising had severely shaken the hostile oppressive state power. In Finland the proletarian class struggle became part of the national independence movement. Led by the Social Democratic Party and supported by the national-bourgeoise, the revolutionary proletariat extorted from Russian tsarism by a heroic general strike, the beginnings of national autonomy and the right to vote for the Landtag, which at that time could justly call itself the most democratic of all franchise systems. It was universal, direct, secret and equal and conferred active or passive rights both on men and women. The firebrand of the Russian revolution set alight the energy and will to fight of the Austrian proletariat and of its leader the Social Democratic Party. It did not come to a general rising over there in the struggle for franchise. Strong determination to carry it out and thorough preparation for it were sufficient to deal a death blow to the hated limited system of franchise, and to win universal or rather manhood suffrage. The Social Democratic leaders of both countries seem to have forgotten the revolutionary origin of the “democracy” which they offer to the workers in lieu of revolution. They are among the most venomous haters and detractors of the Russian Revolution which developed into the conquest of State power and the establishment of the Soviet Republic with proletarian dictatorship. An irony of history and the indelible sign of the most vulgar bourgeoisisation.

Could not one imagine that the Russian revolution of 1905 would as a matter of course produce great results in Germany? The objective historical prerequisites were there. The deprivation of the franchise in Saxony, the interference of the supreme authorities with the right of association and assembly, the stub- born refusal of a democratic franchise in Prussian and the adventurous imperialist policy dictated by Wilhelm’s vainglorious whims all this combined added zest to the influence of the Russian revolution. Therefore the bold revolutionary attack of the workers and peasants on tsarism was welcomed by the German workers with great joy and enthusiasm. They felt it to be an example to be followed and a warning that the battle was imminent. But what was really lacking was leadership by a proletarian class party, capable of intensifying, raising and welding together the revolutionary mood of the masses into an unshakable will to fight. But the Social Democratic Party lagged far behind the revolutionary mood of the masses, like the whilom Landsturm lagged behind the regular forces in the struggle for supremacy between Austria and Prussia in 1866.

The revolutionary vanguard of the German working class was filled with enthusiastic solidarity for the workers and peasants in Russian who wanted to break the chains which kept them so long enslaved. When the Social Democratic Party Congress met in Jena in 1905 the political resolution of the Party Committee did not originally contain even the least allusion to the Russian revolution. It was only when from the Left someone moved a resolution in keeping with the great event that the leaders “of the international liberating Social Democracy” were induced to add to the expressions of their adhesion to principle and of their political perspicacity, a few sentences to welcome the most important event of the times. Naturally on the supposition that the special resolution would not then be brought forward. More significant even than this episode “behind the scenes” was the explanation how it happened that the text of the official resolution had not mentioned the Russian revolution by a single word, namely because of excessive political wisdom and precaution. No information had as yet been received about the details of the rising and it was not certain what the issues of the revolutionary struggle would be. This simply meant: a brotherly handshake and a wreath of laurels for the avowedly victorious revolution, and at the same time an open door for the cowardly retreat from a brutally defeated revolution. The Marxist spirit of the historic understanding for the driving powers of revolutionary mass initiative was just gone to the devil, there only remained philistine phlegma of an insipid opportunism, which only worships success from which it can make capital.

But in spite of everything the powerful breath of the revolution had stirred up the proletarian masses. The pusillanimous petty-bourgeois wisdom of the Social Democratic leaders who aped statesmanship could not but be to a certain extent influenced by the accomplished fact. It continually cropped up in the discussions on the political mass strike and helped the waverers and doubters to come to a decision which was decidedly “veering to the left”. Contrary to the Cologne Trade Union Congress the Party Congress declared that in principle the mass rising was one of the best weapons in the struggle, a weapons for the liberation of the proletariat through the bestowal of rights such as universal franchise, the right of association, etc. The radicals were jubilant over this victory. However, a year later the Mannheim Party Congress put an end to this short summer joy, and the discomforts of winter ensued. The Party Congress brought the capitulation of the advocates of the revolutionary mass strike before the narrow reformist hostility of the general Commission of the trade unions. It did not rise to the occasion by issuing the slogan of the mass strike for the franchise struggle in Prussia. The defeat of the Russian Revolution overshadowed the decision and even had a damping effect on Bebel’s temperament and attitude.

The decision which breathed resignation prevented the very necessary mobilisation of the Party for a far-reaching class struggle. But it did not extinguish the consciousness which the Russian Revolution had awakened in hundreds of thousands of brains, which were struggling and seeking for truth. Innumerable meetings throughout the Reich had turned their attention to the heroic struggle of the Russian workers and peasants and had expressed solidarity with them. At first this too met with resistance. Leading “radical” comrades in Berlin, which set the tone, would have nothing to do with such solidarity meetings. The reasons for their refusal were: such meetings would result in endless lawsuits for the Party and for every speaker in years of imprisonment. Meetings and demonstrations in sympathy with the Russian Revolution became only possible after the Berlin women comrades the Prussian association law placed them at that time organisationally outside the Party – put the men comrades to shame by convening public meetings with the much dreaded agenda. This broke the spell, as is shown by the daily press of that epoch.

The scientific literature of the German Social Democrats benefited very much by the revolution of 1905. The “Neue Zeit” is a perfect mine of wealth in support of this. Kautsky’s profound insight as the keeper of the holy grail of pure Marxism did not foresee at that time that the revolutionary Russian labour movement would hatch out the Basilisk egg of Bolshevism. He looked upon the Russian Revolution as a mountain spring which would give freshness and strength to the fighting energies of the West European proletariat and raved about the “revolutionary international hegemony of the Young Russian working class.” He considered the Russian Revolution as a peculiar historical process on the border of bourgeois and Socialist society, as a process which accelerates the disintegration of the bourgeois order and also the advent of Socialism. One could still feel the heartbeat of the Russian Revolution in the attitude to the situation and the task it created. The outcome of this attitude was Kautsky’s first uncastrated edition of his pamphlet “The Way to Power”. I should like to remind you of the following passage: “In a state with such a high industrial development as Germany or Great Britain, the proletariat would be probably already strong enough today to conquer State power, and it would find already today economic conditions enabling it to set up a state power capable of replacing capitalist enterprises by social enterprises.” What Kautsky has written of the revolution of 1905 as an admirer and learner shows vividly how deep Kautsky, the hater and detractor of the revolution of 1917, has fallen as a theorist and as a man.

The ripest theoretical fruit of the first Russian Revolution in Germany was Rosa Luxemburg’s pamphlet on the political mass strike. This pamphlet is the creation of a genius with Marxist training. It breathes understanding of and enthusiasm for this revolution. In this pamphlet we do not only hear the voice of the scientific searcher for truth, but also the voice of the champion of revolution, who longs to give form to another social life. With a stroke of the pen Rosa threw aside in this pamphlet all the former definitions, classification, regulations, etc., on the general strike. She establishes its historical nature simply and yet distinctly as “the classical form which the proletariat moves in revolutionary situations.” She shows that it is many-sided and continuous like life itself. For she had known of it as active life, she had observed it and helped self-sacrificingly to carry it out during the time when he did her revolutionary duty in Poland. Born of the revolutionary struggle of the Russian and Polish workers, this pamphlet, published by the then very radical Hamburg Party organisation, was to be an inspiring bugle call for the German proletariat to join the revolutionary struggle. It is such a bugle even now in spite of the fact that some of the arguments are out of date.

But the influences which led to the growing bourgeoisation of the Social Democracy and the trade unions and to their bankruptcy as organs of the proletarian class struggle had more to do with the shaping of conditions in Germany and the faith of the workers than the Russian Revolution of 1905. The more acute the class differences in state and economic affairs, the fiercer the exploitation of the masses by imperialist capitalism, the bolder the advance of reaction all along the lines, in a word the more insistently the situation demanded that the German proletariat should take up revolutionary fighting methods and weapons, drawing practical conclusions from the lessons of the Russian revolution, the more pacific was the action of the Social Democrats, the greater their belief in the efficacy of reform, the more determined were they to discourage every form of mass initiative. A contributing factor to this in the dialectical metamorphosis of historical life was the revolution of 1905. It increased the fear of the reformist leaders of mass movements which go ahead without the least respect whatever for bourgeois law and order. The so-much advertised action for the introduction of universal suffrage in Prussia resulted only in well-organised, but ineffective demonstrations. The Social Democrats with their usual lack of courage and fear of responsibility failed to call a general strike and thus give an impetus to the class struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie throughout the Reich and to lead the workers into the battle. Into a battle which from the historic viewpoint was of a much higher value for the conquest of state power than the bits of paper thrown into the ballot box. The renunciation of the revolutionary struggle of large masses for universal franchise was the prelude of the shameful pact of the Social Democrats with imperialism in the world war, of their treacherous coalition with the bourgeoisie in the post-war period and of their cowardly renunciation of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

But nevertheless the light emanating from the first Russian revolution has had its effect on the minds and trend of thought of the German proletariat, it roused their fighting enthusiasm. These emanations have joined forces with the bitter experiences of the imperialist contest for power of the capitalist states and its effect on the everyday life of the proletariat, they have joined forces with the lessons of the victorious Russian revolution of 1917, developing into a mighty flame. And this flame brings light into the minds of the masses and rouses their enthusiasm. The German proletariat has much to make good. It will do this under the leadership of the Communist Party which through hard struggle must learn to fulfil its double task: To arouse revolutionary mass initiative and to develop it into a purposeful self-sacrificing will to fight, to acquire through the development of its own ideological and organisational activities, the capacity to lead and to have confidence in the leadership, faithful to revolutionary Marxism, in the spirit of Lenin. For this is the indispensable pre-requisite for that daily work and struggle which can create mass initiative and lead it. Mass initiative whose aim is: conquest of power and establishment of proletarian dictatorship. Not only mass initiative with the heroism of the Russian revolution of 1905, but mass initiative capable of emulating the triumph of the Red October of 1917.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1925/v05n76-oct-26-1925-inprecor.pdf