Charmion von Weigand reviews Walter Quirts’ first solo exhibit at the Julien Levy Gallery in 1936.

‘The Art of Walter Quirt’ by Charmion von Weigand from the New Masses. Vol. 18 No. 13. March 24, 1936.

ONE of the greatest errors made by the critics who reported the exhibition of Walter Quirt’s paintings (Julien Levy Galleries) has been to call him a “revolutionary Dali.” Quirt’s unified, logical synthesis compressed into exquisite miniature painting is the antipodes of the irrational, intuitional, nightmare dreams of Surrealism. Quirt and Dali have little in common except a love of meticulous painting on a miniature scale and an ability to see objects realistically in unexpected and novel relationships.

Quirt’s exhibition as a whole might be termed The Death of Humanism. It is an ironic comment on the present state of our society in relation to the ideals which it once promulgated at the beginning of its development. To underscore the irony, Quirt has consciously or unconsciously used co positional motifs which derive from the early Renaissance painting.

His models seem to be the Florentine painters of the early Renaissance the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the moralist painters of German Reformation- Breughel and Hieronymous Bosch. He applies color in their manner and uses their precise linear perspective, whose rules were worked out experimentally at that period. Quirt’s painting is tight, like that of early realistic painting in Florence; it employs classical composition. His is a self-imposed restraint, the better to emphasize his meaning. Actually he rejects the esthetic of classicism by giving a superb satire on it.

Quirt is a transition artist. He is an American with the inherited traditions of European culture. He is at the same time a revolutionary artist who dreams of a new world. He therefore finds himself at the crossroads between two cultures- one directed to the future and the other built on the past. His work is a resume of painting tradition derived from the Renaissance- a return to the sources of our culture and a demonstration of how these sources have been rejected in essence, while the empty shell has continued to receive lip-service.

In taking the old classical form of the Renaissance and imbuing it with new content, Quirt is doing what the Constantinian artists of Rome did in an earlier age: they used the iconography of Roman art to embody in it the new Christian legend, which was in the process of forming itself.

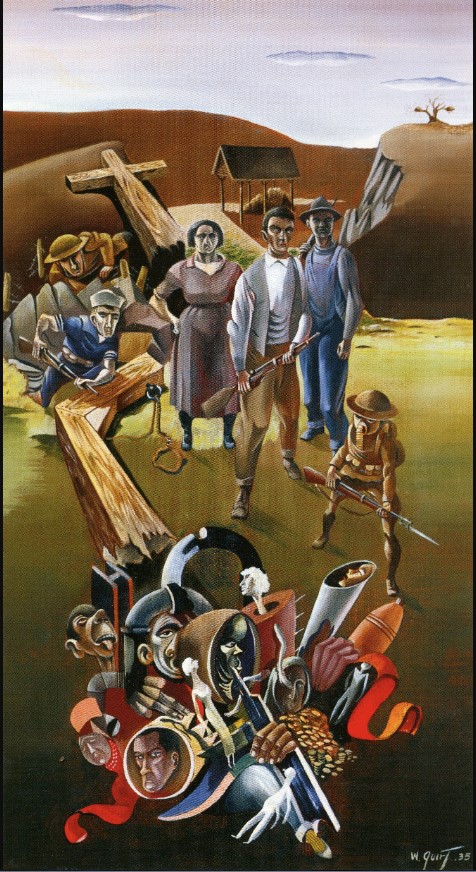

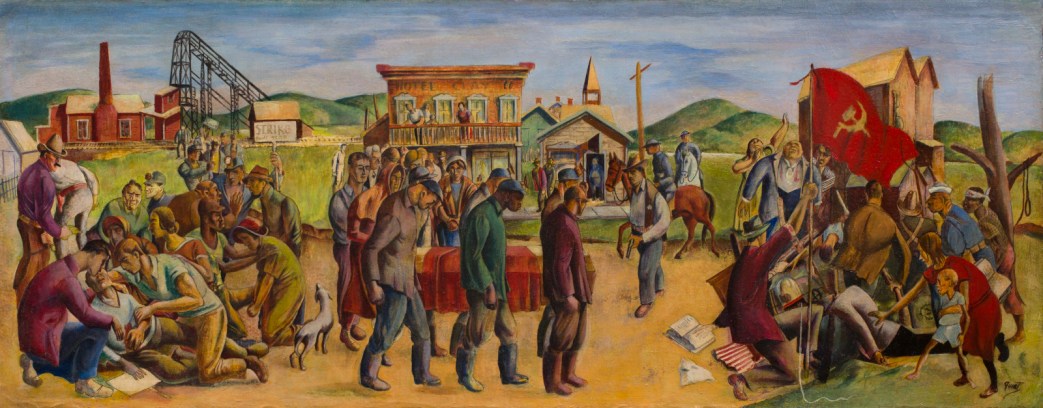

In such a manner Quirt, on the collapsing structure of bourgeois culture, which saw its dawn in the Renaissance, raises the revolutionary banner. Yet as culture is continuous and proceeds historically with few breaks, he uses the old forms- rejecting the decadent researches of modernist and surrealist art for a form created in the youth of the present system. He uses Marxism as the yardstick to measure the shortcomings of American life and the position of the workers. He strips the garments from idealism and reveals the greed, hypocrisy and corruption underneath. Even the titles of his pictures are moral lessons: etched in ironic derision: “Give us this day our Daily Bread,” “Consider the Lilies of the Field,” “Inferior” (of the Negro), “Opium of the People,” etc.

Take for example one of the most complex of his compositions: “Morals for Workers.” Here the painter indulges in an orgy of moral indignation. Every one of the conventional virtues so carefully inculcated in American institutions is held up for inspection and mocked at with bitter irony. Centered in the composition is that golden girl of the American magazine cover- emaciated and in rags. To her left in a rickety shack sit the worker’s family- the sacred family of Mary, Joseph and the child, hungry but putting their last penny in the savings bank thrift is a virtue. Cleanliness is next to godliness, so the poor Hooverville tramp washes in the cracked bowl outside while a spry old saint in a red nighty blesses his efforts-motif of the Baptism. At the top of the picture, the worker punches the time clock, for punctuality will reward you and if not you, the capitalist who waits. Far to the right of the golden girl, workers lean from their tumble-down hut to salute silken American flags-patriotism is sacred. Nearby a young boy studiously reads books with the picture of Lincoln beside him- application will make you Horatio Alger or the president. Below in the furthest left corner the ragged worker embraces the bloated capitalist love thy neighbor as thy self-and the days of your hunger and exploitation will be long.

Such painting belongs spiritually to the same realm as Giotto’s frescoes of the virtues and vices and those moral sermons, in fresco, of the Siennese with their vision of the Last Judgment. Quirt’s whole gallery of pictures is a last judgment on bourgeois culture based on the exploitation of the worker and the farmer-the two stalwart heroes who appear always united in his paintings, martyrs of a new epic which is yet to be portrayed.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1936/v18n13-mar-24-1936-NM.pdf