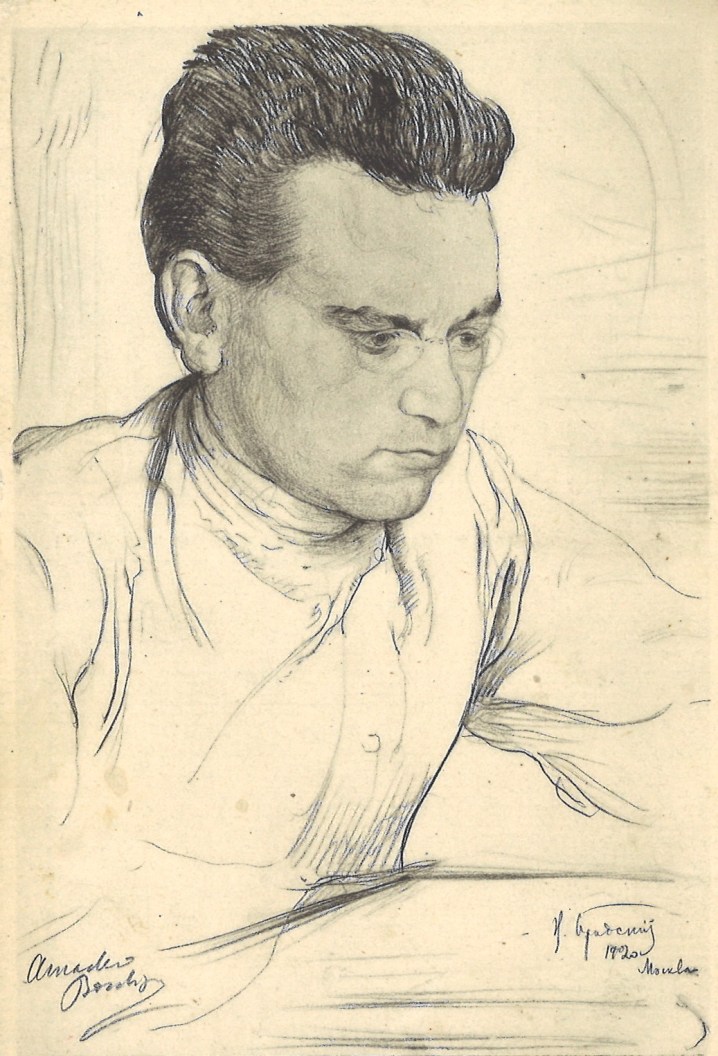

A fascinating document from a report by Gramsci, recently made Party Secretary, before the leadership of the Communist Party of Italy on its internal life. With particular focus on the faction around Amadeo Bordiga then in the process of splitting with the Comintern, Gramsci also details other tendencies in the Party.

‘The Situation in the Communist Party of Italy’ by Antonio Gramsci from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 5 No. 60. July 30, 1925.

Comrade Gramsci recently gave a detailed report before the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Italy, on the inner situation in the Italian Party. We give below the most essential parts of this report. Ed.

The conditions under which the C.P. of Italy has to fight, are extremely difficult. It has to fight on two fronts against the Fascist terror and against the reformist terror exercised by the trade unions of the D’Aragona type. The regime of terror has considerably weakened the powers of the Italian trade unions. The reformist leaders exploit this state of affairs for their own ends, and undermine the action of the revolutionary minority in the trade unions. The masses are anxious for unity, and to carry on the fight within the “Confederazione Generale del Lavoro” (Federation of Free Trade Unions). The reformist leaders thus find themselves obliged to oppose the organisation of the masses. At the last congress of the Trade Union Federation D’Aragona proclaimed that the number of members in the Trade Union Federation must not be permitted to exceed one million. This means that the leaders of the free trade unions only want 5,5 % out of 15 million Italian workers to be organised. As adherents of the Social Democratic policy of joint action with the bourgeois parties, they do not want to organise the peasantry, since this would weaken the basis of the bourgeois democratic parties.

How is reformism to be combatted and yet a split in the trade union movement to be avoided? We see one possibility only: the organisation of factory nuclei. Since the reformists oppose the concentration of revolutionary forces, it is the task of the factory nuclei to gather all the factory workers around the Party, and to strengthen the “Inner Factory Committees” or, where these do not exist, to form Propaganda Committees. These last should be mass organisations adapted to developing the trade union movement, and to participating in the general struggles against capitalism and against the ruling regime.

In this respect the Italian communists are in a much more difficult position than the Russian Bolsheviki before the war, for they have to hold their own simultaneously against Fascist reaction and against reformist reaction. But the more difficult the situation, the firmer must be the establishment of the communist factory nuclei, both with regard to ideology and to organisation.

In these questions there is no disagreement in the standpoints held by the Communist Party of Italy and the Communist International. The Italian Commission of the Enlarged Executive was occupied solely and exclusively with the inner Bolshevisation of the Italian Communist Party.

Comrade Bordiga, who was called upon to take part in the work of the Enlarged Executive, has declined to do so, although he agreed, at the V. World Congress, to form one of the Executive of the Communist International. His attitude is the more regrettable that in the Trotzky question he adopted a standpoint not only acutely antagonistic to that of the Executive, but even antagonistic to that of Trotzky himself. It is to be regretted that comrade Bordiga would not take part in the discussion on the Trotzky question; if he had gone to Moscow for this purpose, he would have had the opportunity of hearing the views and proclamations of the Executive and the opinions of the Parties, and could at the same time have expressed his own views.

The Commission which should have discussed this question with comrade Bordiga has continued to pursue the policy which the Party must pursue if the Bolshevist idea is to be helped to victory. It has examined the general conditions ruling in the Communist Party of Italy with reference to the five fundamental characteristics demanded by Lenin of every really revolutionary Communist Party. These five points are as follows:

1. Every communist must be a Marxist. (Today we say: Marxist-Leninist.)

2. Every communist must take his place in the front ranks of proletarian action.

3. Every communist must abhor mere revolutionary phraseology, he must be at the same time a revolutionary and a real politician.

4. Every communist must submit his will to that of his Party, and judge everything from the standpoint of his Party. (He must be a truly disciplined member of the Party, in the highest sense of the word.)

5. Every communist must be an internationalist.

We may say that the C.P. of Italy fulfils the second condition, but none of the other four.

The C.P. of Italy lacks a thorough Marxist-Leninist teaching. In this lack we observe the remains of the traditions of the Socialist movement in Italy, which avoided those theoretical discussions which might have aroused the interest of the masses, and contributed to their ideological education. This state of affairs is extremely regrettable, and comrade Bordiga contributes to its continuance by confusing the tendency, peculiar to reformists, of substituting general “cultural work” for revolutionary political action, with the endeavours of the Communist Party to so raise the intellectual level of its members that they are able to grasp the immediate and distant goals of the revolutionary movement.

The Party has succeeded in developing a feeling for discipline in its ranks. But a lack of international spirit is still observable in its relations to the Communist International. The Bordiga group, which thinks to ennoble itself with the designation of “Italian Left” has created a sort of local patriotism inconsistent with the discipline of a world organisation. The situation created by comrade Bordiga is similar to that created by comrade Serrati after the II. Congress in Moscow, and that situation led to the expulsion of the Maximalists from the Communist International.

The greatest weakness of the Party lies however in its love for the revolutionary phrase so often stigmatised by Lenin. If this does not characterise Bordiga himself, it characterises the elements grouping themselves around him. The extremism of Bordiga is the result of the special conditions of life obtaining among the Italian working class. But the Italian working class forms only a minority of the working population. It is concentrated for the most part to one part of the country. Under these circumstances their Party falls easily under the influence of those middle strata who are capable to a certain extent of steering the workers into a course actually opposed to their interests. On the other hand the situation in the Socialist Party up to the time of the Leghorn Congress was calculated to develop Bordiga’s ideology.

Lenin, in his “Infantile Diseases of ‘Radicalism’ in Communism”, defines this situation in the following sentences:

“In a Party where there is a Turati and a Serrati who does not combat Turati, there must inevitably be a Bordiga as well.”

But it is less naturally inevitable that comrade Bordiga should have preserved his ideology in our Communist Party. The struggle against opportunism has rendered Bordiga so pessimistic that he is sceptical as to the possibility of saving the proletariat and its Party from the intrusion of petty bourgeois ideology, except by the employment of extremely sect-like tactics, which would however contradict the two leading principles of Bolshevism: The unification of the workers with the peasants, and the hegemony of the proletariat in the revolutionary movement.

Are there still other tendencies in the Communist Party of Italy? What is their nature, and what dangers do they represent? An examination into the inner situation in the Party convinces us that it has not yet attained that degree of revolutionary maturity characteristic of a really Bolshevist Party, and that it has not even succeeded as yet in amalgamating into a whole the various groups of which it is composed. The C.P. of Italy has been formed out of three groups.

1. Bordiga’s antiparliamentary fraction (fraction abstaining from voting).

2. The group of the “Ordine Nuovo” (“New Order”) and of the “Avanti” (“Forward”) in Turin.

3. The Gennari-Marabini group. Bordiga’s fraction was formed as national organisation before the Leghorn Congress, but it occupied itself solely with the inner life of the Socialist party, without possessing the political experience imperative for mass action.

The “Ordine Nuovo” group formed an actual fraction in the. province of Piedmont. It developed its action among the masses, and showed itself capable of establishing a close connection between the inner problems of the Party and the demands of the Piedmontese proletariat.

The overwhelming majority of the members of the C.P. of Italy are elements which remained in the Communist International after the Leghorn Congress, headed by numerous of the old leading comrades of the Socialist party: Gennari, Marabini, Bombacci, Misiano, Salvadore, Graziadei etc.

Without a full comprehension of the various elements composing the C.P. of Italy it is impossible to understand either its crises or its present situation.

The situation was made worse last year by the affiliation of the “Fraction of the III. International” of the “Maximalist Party” to us. This “Fraction of the III. International” formerly carried on bitter personal and sectarian struggles within the Maximalist party; it deals with the fundamental questions of policy and organisation as being of secondary importance.

For instance there is a Graziadei question. We have to combat the deviations spread abroad in his last book. It would be wrong to assert that comrade Graziadei is a political danger, and that his revisionist conception of Marxism could generate an ideological current. But his reformism might contribute to strengthen the Right tendencies still concealed in the Party.

The affiliation of the “Fraction of the III. International”, which has retained its Maximalist character to a great degree, might even afford the Right tendencies a certain organisatory basis.

It must be granted in general that a Right danger is probable in our Party. The masses, disappointed by the failures of the “constitutional opposition” (of the Socialists and bourgeois), have streamed into our Party and strengthened it, but not to the extent to which they have streamed to Fascism, which has succeeded in establishing itself. In this situation a Right wing might easily come into existence if it does not exist already which, despairing of being able to overthrow the Fascist regime rapidly enough, adopts a policy of passivity which would make it possible for the bourgeoisie to exploit the proletariat for anti-Fascist election manoeuvres. In any case, the Party must recognise that the Right danger is a probability, and must first meet this danger by ideological influence; later, if necessary, with the aid of disciplinary measures.

The danger from the Right is merely probable, whilst that from the Left is obvious. This Left danger forms an obstacle to the development of the Party. It must therefore be combatted by propaganda and by political action. The action taken by the “Extreme Left” threatens the unity of our organisation, for it strives to form a party within the Party, and to replace Party discipline by fraction discipline. We have not the slightest wish to break with comrade Bordiga and those who call themselves his friends. Nor do we seek to alter the fundaments of the Party as created at the Leghorn Congress and confirmed at the Rome Congress. What we must demand is that our Party does not content itself with a mechanical affiliation to the Communist International, but actually appropriates the principles and discipline of the Comintern. But in actual fact 90% of our Party members, if not more, have today no knowledge whatever of the methods of organisation upon which our relations to the International are based. We believe that we shall arrive at an understanding with comrade Bordiga, and we trust that he believes this a well, and as desirous of it as we are.

The C.P. of Italy will hold its Conference shortly. In the discussion preceding the Party Conference we shall have to deal with the present political situation and the tasks of the Party in Italy. Since the last parliamentary elections the C.P. of Italy has been carrying on energetic political work, participated in by most of its members. Thanks to this work, the Party has tripled its membership. Our Party has shown much energy and realisation of actualities in preaching the problem of revolution in Italy as the problem of the alliance between the workers and the peasantry. In short, the C.P. of Italy has become an important factor in the political life of the country.

In the course of the above mentioned work a certain unification of character, a homogeneity has been developed within the Party. This homogeneity, one of the most important results of our Bolshevisation, must be firmly and finally established by our Party Conference. We shall discuss the international situation and the proportions of social forces in Italy, concentrating our efforts upon the two following points: The development of our Party, which must be such as to render the Party capable of leading the proletariat to victory (the problem of Bolshevisation); and the political cation which must be carried on for the purpose of gathering together all anti-capitalist forces and establishing a workers’ state. To this end it is necessary to study the conditions in Italy with the utmost exactitude, so that the revolutionary alliance between the proletariat and the peasantry may be established, and the hegemony of the proletariats thus secured.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1925/v05n61-jul-30-1925-inprecor.pdf