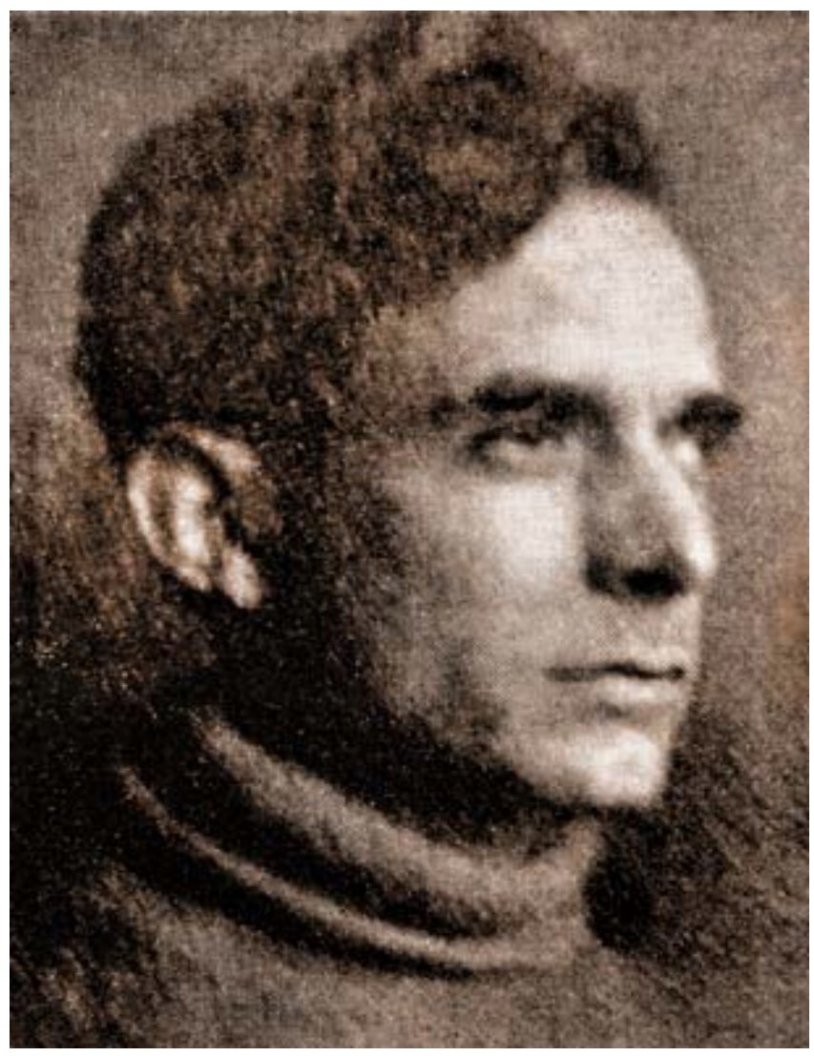

Founding U.S. Communist Louis C. Fraina was brought up in poverty in New York’s Little Italy, leaving school at 14 to work in a tobacco factory after his father’s death. Entirely self-taught, Fraina was only 21 years old when he wrote this extremely literate, deep-dive into the Futurist art movement and the larger role of art in the working class’ struggle to emancipate itself.

‘The Social Significance of Futurism’ by Louis C. Fraina from New Review. Vol. 1 No. 23. December, 1913.

“The ideals of mechanical progress will influence his heart.” F.T. Marinetti.

There is a type of mind, conservative as well as radical, which has a stereotyped conception of new ideas in art. The conservative indiscriminately condemns; the radical as indiscriminately praises. There is another type, more grotesque still, the man who traces, new ideas in art and literature to pathologic causes. Disciples of this “pathologic” or “physiologic” interpretation are many, even among Socialists. The social milieu, which determines ideas and movements, seems to these folks a closed book or a mere figure of speech.

The New Art, of which Cubists and Futurists are the most characteristic representatives, is being interpreted in this pathologic spirit. This art is said to be the product of abnormal, pathologic brains; of men who suffer from neurosis and downright degeneracy. But even if we assume that “decadent” manifestations in art are pathologic, does this account for their form of expression, for the movement itself? Was Francois Villon’s art identical with that of Paul Verlaine or Oscar Wilde? “Degenerate” artists never cease; if at a given moment they produce movements, it is because they express a cultural urge conditioned by the social milieu.

Byronic Romanticism, that legitimately exaggerated revolt against the crushed ideals and conservative reaction succeeding the French Revolution, was, and sometimes still is, considered pathologic. Not a few critics ascribed Wagner’s revolutionary music to pathologic degeneracy-that music which expressed strident, inchoate revolt amid the discordances of industrial civilization, a music cast in the mold of Nietzsche, human-symbol of Wagner’s stormy generation. The music of Richard Strauss is generally considered decadent. Yet Strauss’ music expresses the Pagan spirit now transforming our moribund culture. That Strauss does not express the Greek spirit full-orbed is due to the Pagan spirit being immature and corrupted by contact with capitalist degeneracy- a bourgeois and not a proletarian manifestation. Whosoever mentions pathology in this connection must consider pathologic the vital, universal Pagan urge of our generation.

Three men symbolize, artistically and socially, the Russia of recent times-Tolstoy, Gorky, Artsibasheff. Tolstoy’s passive resistance doctrines flourished in Russia during the revolutionary ebb of the eighties; the passive theory expressed social discouragement, failure, despair. Gorky’s virile, revolutionary literature coincides with a virile, active revolutionary movement. Since Bloody Sunday and its reaction, the Russian youth, discouraged, hopeless, expressed its spirit and energy in an orgiastic saturnalia, a mood voiced in Artsibasheff’s “Sanin”. A multiplicity of “Sanin Clubs” attests the social urge. The revolutionary reaction expresses itself in another form in Andreiev’s morbid gloom, corrosive doubt and revolutionary paralysis.

Art reflects life; it is social and not individualistic. Therein lies the value of art and literature to the student of history. Vital art expresses the vital urge of its age. Aspirations continually change with changing social conditions; art changes in harmony therewith, not only in spirit but also in methods. Art appears deadly opposed to pouring the wine of new aspirations into the bottles of old methods.

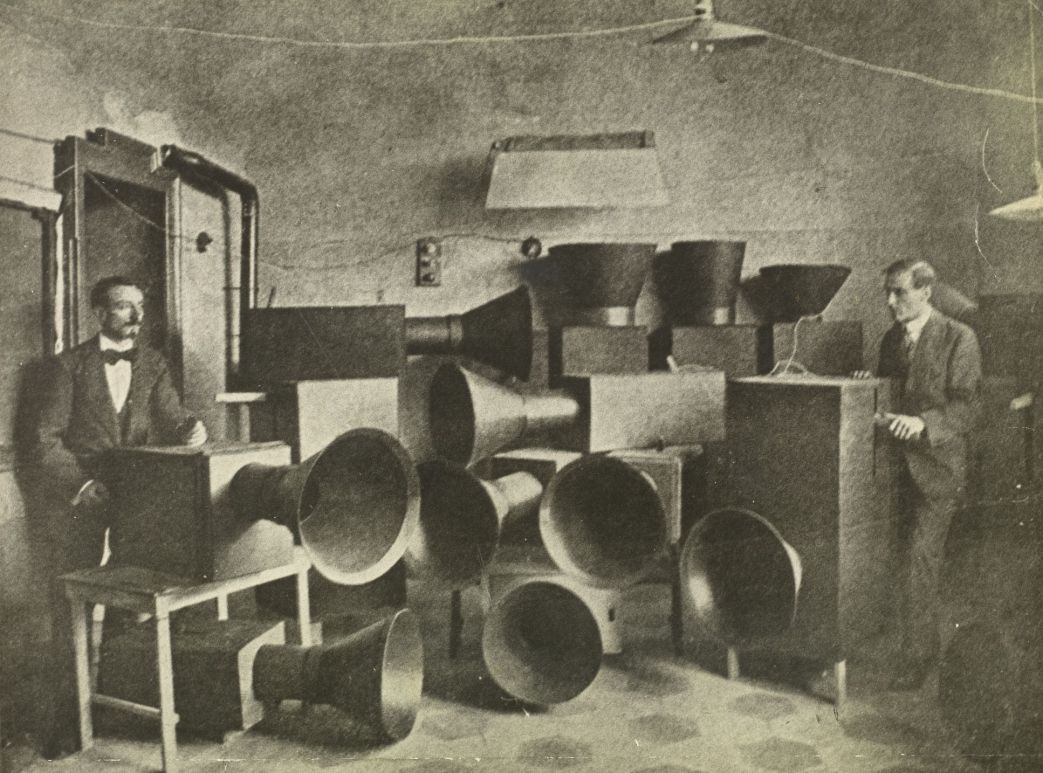

Considered in this light, the New Art expresses capitalism. It is the art of capitalism-not the “art of decadent and dying capitalism”, as some would have it, but of capitalism dominant (Cubism) and capitalism ascending (Futurism). The aggressive, brutal power of Cubism and Futurism is identical with the power and audacity of capitalism, of our machine-civilization. The New Art is as typical of capitalism as the architecture of the skyscraper. Paul Lafargue somewhere says that machinery induces in the worker a disbelief in God, while the mechanism of stock exchange operations develops a sort of fetichistic religion in the bourgeois. If machinery affects such a spiritual matter as religion, small wonder that the spirit and power of machinery should transform art.

Cubism, as I said, is the art of capitalism dominant; Futurism the art of capitalism ascending, struggling for ascendancy. This accounts for the Cubists having a definite technique, while Futurists are vague and indefinite, failing largely to embody creed in artistic productions. Futurism paints the spirit of machinery-energy, motion, aggression. Cubism does more. Cubism transfers the technique of machinery, so to speak, to the canvas. In the words of a writer who sees a glimmer of the truth: “The line of grace has been replaced, in the Cubist pictures, by the lines of utility and strength. Curves have been discarded for angles. The Cubists paint as if there were nothing but mechanism in the universe.”

Futurism is the most interesting manifestation of the New Art. While Cubism simply expresses artistically the spirit of capitalism, Futurism in Italy, its birthplace, is a utilitarian movement seeking to establish the supremacy of capitalism. In an article in the St. Louis Mirror (May 16, 1913) on “Futurism in Italy”, the first sociological interpretation of the movement, I said:

“Italian aspirations for industrial progress and the effort to throw off the dead, fossilized hand of the Medieval past, have largely crystallized the Futurist movement.

“In the fourteenth century Italy’s industrial and commercial supremacy produced the cultural efflorescence of the Renaissance When the center of commercial power shifted to North Europe, Italy sank into the slough of Medieval darkness. The serfs who had been freed from the soil and migrated into the towns as proletariat, Marx says, ‘were driven en masse into the country, and gave an impulse, never before seen, to the petite culture, carried on in the form of gardening.’ Once a purely ‘geographical expression’, Italy has since the Risorgimento been largely an agricultural expression. Italy needs industrial expansion. Petty agriculture hampers national growth. Semi-feudal conditions remain to be overthrown. But the Italian bourgeois are inept, cowardly, narrow-visioned. They possess little initiative, nor the courage to conceive large projects. In addition, Italy lacks natural advantages- coal and iron, factors indispensable for industrial development, the abundant possession of which makes China an ominous portent in the world market. Italy, accordingly, has thrived on its petty agriculture and its past, feeding on tourists and making cash out of the ‘grandeur that was Rome. Virile Italians are in revolt at this social degeneracy. Instead of worshiping the past and exploiting its grandeur, Futurists demand overthrow of the past, the forging ahead of industrial progress. Their slogan is, “Down with the grandeur of the past! Up with the grandeur of the present and the future! Futurism is the apotheosis of industrialism.”

Futurism, accordingly, emphasizes all that is distinctively capitalist as against that which is feudal or semi-feudal. The following passages from F.T. Marinetti’s manifesto, published in the Paris Figaro in 1909, briefly and comprehensively express this spirit:

“Literature having up to now glorified thoughtful immobility, ecstasy and slumber, we wish to exalt the aggressive movement, feverish insomnia, running, the perilous leap, the cuff and the blow. “We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new form of beauty, the beauty of speed. A race-automobile is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

“There is no more beauty except in struggle; no masterpiece without the stamp of aggressiveness. Poetry should be a violent assault against unknown forces to summon them to lie down at the feet of man.

“We will sing the great masses agitated by work, pleasure or revolt; we will sing the multi-colored and polyphonic surf of revolutions in modern capitals; the nocturnal vibration of arsenals and docks beneath their glaring electric moons; greedy stations devouring smoking serpents; factories hanging from the clouds by the threads of their smoke; adventurous steamers scenting the horizon; and the slippery flight of aeroplanes.”

In these vivid, incisive words Marinetti expresses the cultus of capitalism.

Industrially, capitalism produces a new economic power, “the collective power of masses” (Marx); esthetically capitalism produces a new beauty, the “beauty of speed”. Futurists idealize motion, speed—the very essence of industrial society. Futurist art attempts to express motion, much as the impressionists portrayed light in action and nature’s evanescent moods. Futurist art, accordingly, even though not fully materializing its ideal, possesses a nervous force and power startingly vivid, oppressive, characteristic of our machine-civilization, of our wireless age.

Terrible as are its evils, capitalism is superior to the cemetery- civilization stifling Italy. Capitalism at least carries within itself the germs of its own destruction, hence of a nobler civilization. Even in North Italy, where capitalism flourishes, traces of feudal psychology persist, encouraged by bourgeois sloth and the Roman Catholic Church. Not only Futurism, virtually all forces in Italy are making for capitalist progress. The imperialistic burlesque in Tripoli may react upon and encourage industrial development. The Camorra trial some years ago marked an epoch: the struggle of capitalist civilization, and all implied thereby, with the remnants of feudal disorder, barbarity and psychology of the masses, centralized in the Camorra, a political machine exploiting and intensifying feudal mentality. As the Rome Tribuna said at the time, “It looks as though the trial would mean the regeneration of Southern Italy”.

The fight of the Futurist, however, is not merely for industrial progress. The demand is for a new culture, based on a new civilization. It is a fight against mental sloth and corrosive romanticism, against the dolce far niente spirit. Action! Motion! Progress! In his fight against the remnants of the past, the Futurist expresses the material facts of capitalist necessity as abstract truth; and insists upon this truth, the sublimated expression of bourgeois aims, as the regenerative power. The Futurist prates of this Truth in typical bourgeois strain, —as something sublime, eternal: “There is no conscience, there is no noble life, there is no capacity for sacrifice where there is not a religious, a rigid, and a rigorous respect for truth.” (Prezzolini, La Voce, April 13, 1911.) Romain Rolland, in the last volume of Jean Christophe, illumines this phase:

“It might be thought that the fire had died down with the closing of Mazzini’s eyes. It was springing to life again. It was the same. Very few wished to see it. It gave a clear and brutal light…The etiquette of parties, systems of thought, mattered not to them: the great thing was to ‘think with courage.’ To be frank, to be brave, in mind and deed. Rudely they disturbed the sleep of their race…They suffered, as from an insult, from the indolent and timid indifference of the elect, their cowardice of mind and verbolatry. Their voices rang hollow in the midst of rhetoric and the moral slavery which for centuries had been gathering into a crust upon the soul of their country. They breathed into it their merciless realism and their uncompromising loyalty.”

All very fine! But this Truth is the sublimated expression of capitalist necessity; this fervent idealism the reflex of capitalist struggle; this Future the dawn of untrammeled capitalist supremacy.

The Futurist demands, figuratively, the destruction of museums and libraries, of the art and literature of the past. This is not a demand for artists and writers alone, who should not “see life through a mist of souvenirs”, but must form standards in harmony with their generation. It is also a social demand. For Italy socially is much of a museum; Rome lives on its classical tradition; Florence is nothing but a picture gallery. This state of things breathes social death. In their place the Futurist demands factories and commerce. And not the Futurist alone. Therein lies the social significance of Futurism. Non-Futurists demand the identical thing. Signor Nathan, the mayor of Rome, uttered the same wish recently:

“Rome must no longer be merely a great hotel, as it was when crowds came to visit the head of Catholicism; Rome must become a great city sufficient unto itself, with its manufacturing quarters and its agricultural zone extending from the mountains to the sea.’ The Futurist spirit is broader than the Futurist movement. It is a spirit that has spread over all Italy. It demands a sweeping out of Italy’s feudal rubbish. The Futurist movement does not consist of artists alone; among its most zealous adherents are sociologists, journalists, politicians, men and women in all walks of life, bound together by the ideal of industrial progress. Much as the Futurists condemn the past, they are hypnotized by the past. They dream of reviving the Imperial Italy of the days when Rome ruled the world, and strive for a terza Roma which shall hold the world in awe.

Futurism is consequently imperialistic. Not merely because of peculiar conditions in Italy; any art which reflects capitalism is necessarily imperialistic; witness Rudyard Kipling. Futurism glorifies war. War is a “measure of political sanitation”, to use Marinetti’s phrase, who believes that “nations should follow a constant hygiene of heroism and take every century a glorious bath of blood”. Marinetti identifies Futurism not only with Italy’s industrial future, but with her imperialistic aspirations as well:

“Our national destiny depends on the Futurist propaganda. As inevitably as the sun rises and sets we shall have to struggle for our life against Austria. If the contest comes when Venice is still sunk in the lethargy of its old romanticism, when Rome is living on its classical traditions, when Florence is nothing but a picture gallery, we are doomed. Furthermore, Tolstoyism and passive resistance are so debilitating the workingmen of Italy that I believe if it is not checked by the awakening spirit of Futurism, the Italian people will be as helpless as sheep before a herd of wolves when Austria marches over the frontier.”

Austrian invasion of Italy is a mere catch-phrase of the politician. Indeed, there is much more possibility of Italy invading Austria in an effort to seize Trente and Trieste. But Marinetti, in his “religious, rigorous and rigid respect for truth”, inverts the problem and falsifies it.

Futurism is the product of peculiar and transitory political and economic conditions in Italy. In this sense, Futurism is comparable to the French Romantic movement. The liberal spirit of the Romantic movement reflected the liberal movement in politics, which, in turn, reflected economic facts. Feudal and bourgeois elements were in revolt against the regime in power. The opposition was a confused one, liberals and absolutists jostling each other. Accordingly, a peculiar feature of the time, noted by Balzac, was that most of the “liberals” were really reactionists, seeking to introduce things of the past. Hence Romanticism’s apotheosis of the past. Victor Hugo fortunately broke the vicious circle of worship of the past, and developed as a consistent bourgeois liberal; the other Romaticists were lost in the shuffle. And when France outgrew the peculiar conditions of 1830, Romanticism decayed; the regime of Napoleon the Little crushed Romanticism completely. When social conditions take the bottom out of the movement, Futurism, as a movement, will doubtless disappear. For it is a wild, social passion of the moment, a storm worn out by its own fury.

But Futurism artistically will not die. International forces aided the distinctive Italian conditions to produce Futurism. Futurism would not possess the artistic maturity it has were it not for this interaction of local and international forces. This is why Futurism, expressing capitalism ascending, possesses many of the characteristics of capitalism dominant. Modified by local conditions, the New Art is yet one in its international expression of the capitalist cultus. Futurism and Cubism will develop, coalesce; and, even more than now, reflect an art typically capitalist.

For this New Art is not a bolt out of a clear sky, as superficial critics, helpless in the face of new phenomena, would have us believe. Literature has been trending in its direction. Zola, with his materialistic precision and application of “scientific principles” to the novel, drama, poetry, adumbrated the movement. In Kipling, the typical Kipling of “MacAndrew’s Hymn”, “The Ship That Found Herself”, and “.007”, machine-inspiration dominates. Machinery acts as the leitmotif, throbbing with life, as inexorable as the passions of man. Machinery urges the action and catastrophe. Kipling humanized machinery; the Cubist and Futurist machinize the human.

There is no inspiration in Futurism for the Socialist. It is remarkable that many American Socialists should hail the New Art as something marvellous, epoch-making. I suspect they are taken in by its grandiloquent phraseology. How can the Socialist find inspiration in an art thoroughly and superbly capitalist?- which, while it expresses the power of capitalism, likewise expresses all that is evil and degrading. Must we then admit that the Socialist is generally only an economic revolutionist, and finds inspiration in bourgeois “revolutionary” art?

Socialist art must not adopt the tools of the bourgeois. Socialist art must forge its own tools, evolve its own methods to express and interpret the new culture which the Socialist movement carries within its folds.

New Review was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. In the world of the Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Maurice Blumlein, Anton Pannekoek, Elsie Clews Parsons, and Isaac Hourwich as editors and contributors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 on, leading the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable archive of pre-war US Marxist and Socialist discussion.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1913/v1n23-dec-1913.pdf