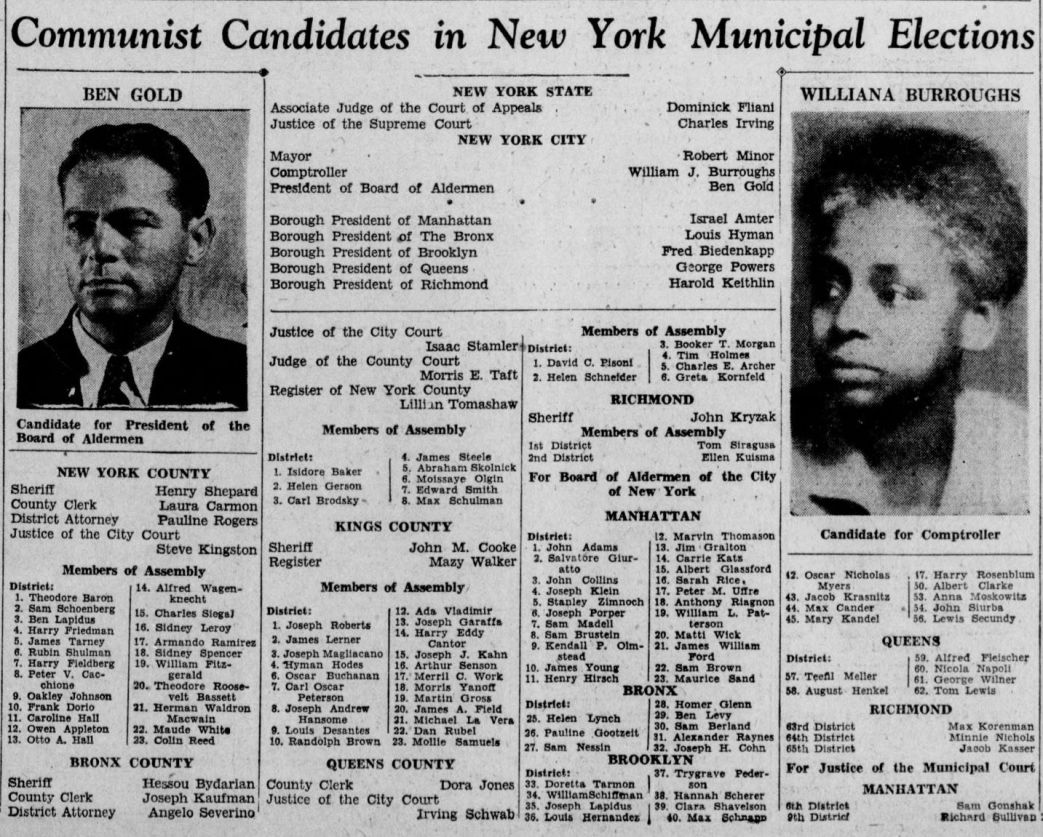

The remarkable life of Harlem activist, Black woman worker, editor of the Negro Liberator, and persecuted public school teacher Williana Burroughs is surveyed in this ‘miniature’ biography by Helen Luke of the organizer who joined the Party in 1926. Also included is a longer article by Philip Sterling on her suspension from New York Public Schools for ‘conduct unbecoming of a teacher’ and subsequent strong run for that city’s Comptroller.

‘Miniatures of Our Militant Women: Williana Burroughs’ by Helen Luke from The Daily Worker. Vol. 11 No. 104. May 1, 1934.

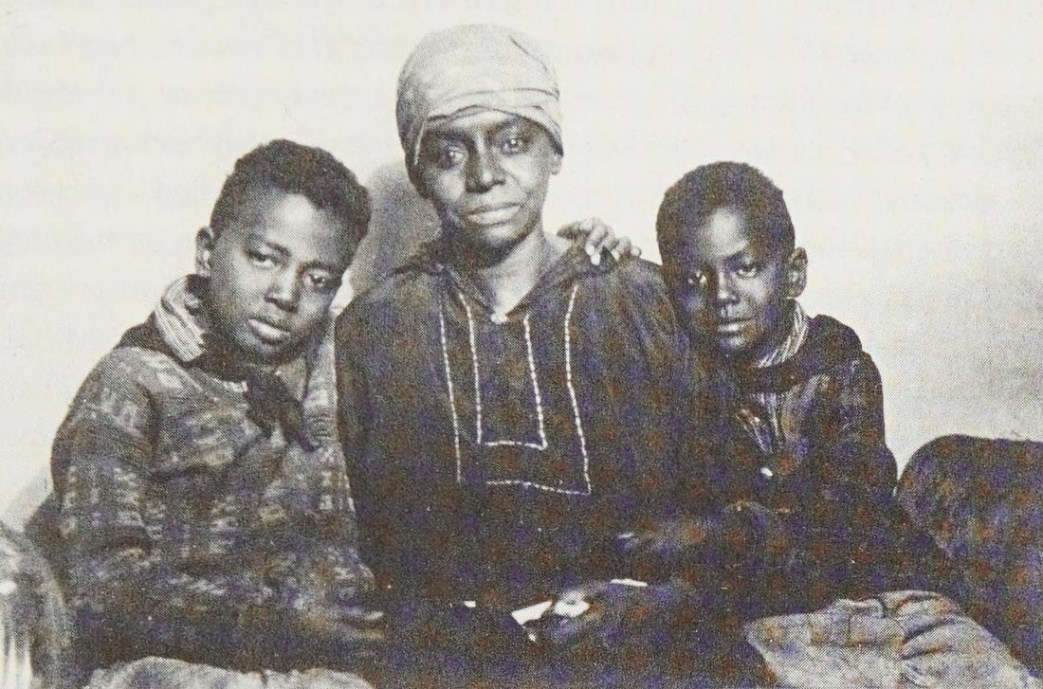

True daughter of the working class, Williana Jones was born in Virginia, of slave-born parents freed by the Emancipation Proclamation. Williana’s mother had been brought up in strictest tradition of unceasing labor as the lot of unhappy race torn from native tropical home: as a tyke of three or four years was perched up on box to busy herself with dishwashing.

This little girl-worker, when she grew up and married, had three babies, one of them Williana. While babies were still very young, father died and Mrs. Jones came to New York hoping to be better able to care for brood.

Found work in domestic service. When unable to keep children with her, placed them in orphan asylum then at 143 St. and Amsterdam Ave. One child died, leaving Williana and brother.

Williana went to school in city, and in times when Mother Jones could keep children where she worked, the little Williana’s services were considered part of labor bought by the mother’s meagre pay. After school she had plenty of work to do, dishes, cleaning, scrubbing-perpetual round of house-drudgery. Sometimes exhausted, stopping to read book, explanation was demand- ed by Mother Jones.

“But I’m SO tired!” Williana would protest.

“Tired!” repeated mother in amazed rebuke “but THAT’S no reason for stopping work!”

As Williana grew older, she continued schooling, working out of school hours: passed through what is now “Hunter” College. Here, finally received meagre payment of five dollars monthly.

During two summers, went out to work caring for children.

After Hunter, in 1903, Miss Jones became a teacher, placed always in working class (primary) schools. With growing knowledge, growing consciousness, grew also urge to help her oppressed race, to seek best way of doing so. Did volunteer settlement work, helped Negro children’s clubs, engaged in other like activities.

Was asked why she did not join a Labor Party. Jim-Crow attitude of Socialist Party repelled her. Experienced years of restlessness in search for correct alignment to aid in deliverance of her people. Like many others, felt that urge to go South to work among her people there: yet felt also, essential futility of individual efforts while pressure from above was not lifted. Meanwhile read widely, seeking a road, Miss Jones married. Had to leave off teaching because of ban on married women teachers. When ban was later lifted, Mrs. Burroughs returned to work. To bear her own four children, was forced to leave again, but later, in need of funds, again returned to teaching.

Finally through persistent inquiry, found way to American Negro Labor Congress, thence made way to Communist Party.

Comrade Burroughs was active in efforts to save Scottsboro Boys, also in Parent Teachers’ Association, and was active member of left-wing group in Teachers’ Union of A. F. of L.

Bronx school teacher, Isidore Blumberg, was expelled in frame-up “open” hearing at Board of Education, due to activity as chairman of Teachers’ Committee to Protect Salaries.

Comrade Burroughs became secretary of Blumberg Defense Committee, and was suspended along with Isidore Begun, another teacher who attempted to defend Blumberg.

Comrade Burroughs was Communist candidate for Comptroller at last municipal elections, polling 30,749 votes, highest number of votes received by any N.Y.C. Communist candidate.

Is now active in our movement; teaches at Harlem Workers’ School, and is contributing editor of the Harlem Liberator.

‘Williana Burroughs Now Communist Candidate for Comptroller’ by Philip Sterling from The Daily Worker. Vol. 10 No. 232. September 27, 1933.

WILLIANA J. BURROUGHS isn’t running for Comptroller on the Communist ticket to catch the “women’s vote.” She is running for that office because, in common with the other leading candidates of the Party, she has proved that she has the attributes of Communist leadership–an understanding of Communist theory, an understanding of the local issues involved in the election, and the willingness and ability to work unsparingly to put into effect the local Communist Party program should she be elected.

The proof of her qualifications, especially in the matter of willingness and ability to work, lies in the fact that she was on the job long before the campaign started. Now immersed in a harassing schedule of speaking dates, committee meetings and campaign conferences, she has unhesitatingly assumed the responsibility of guiding the New Harlem Workers School through the first shoals and rapids in which any new venture sets sail. Only she doesn’t look on her new responsibility as an added burden. She glows with enthusiasm as she speaks of it.

“Unbecoming to a Teacher”

“I was expelled from the New York school system, you know, for conduct unbecoming to a teacher. I was angry of course, because the expulsion was the usual cowardly punishment for radical activity. But I’m not sorry now. This,” she said, indicating her office and the class room beyond it with a gentle sweep of her arm, “this is really teaching.”

Then, still seated sedately before her orderly desk, she swiveled from a small pile of letters, campaign literature and mimeographed oddments, to talk about the election campaign and her particular part in it.

“What makes me think I could handle the job of comptroller?” she laughed in reply to a brazenly provocative question. “Listen, anyone who has run a household for four persons on $20 a month and has worked her way through college on $5 a month should be able to manage the financial affairs of a great city which has plenty of credit and resources.” Then, in a more serious vein, “That is, anyone who is in office under the control and in cooperation with a well-disciplined political party which has the interests of New York’s working class at heart because it is made up of New York’s working class.”

Discusses City Finances

Mrs. Burroughs straightened the little pile of papers on her desk with gentle but effective taps and launched into a discussion of city finances.

“You know, there’s been so much confusion deliberately created by the present administration on the question that it’s hard to make people see that it really is rather simple. The city’s most important financial problem is to find funds for adequate unemployment relief. Even Tammany is beginning to admit that now. Well, when a family hasn’t enough money for all its needs, what do they spend their money on? Why, the necessities of life, food, rent, gas, etc. They don’t pay off debts and they don’t go to the country for a vacation. They cut down on non-essentials. And that’s just what the city of New York would be doing if it were run by the workers instead of by Wall Street bankers through Tammany Hall.”

Mrs. Burroughs, who recently had a taste of Tammany management when she was dismissed from the city schools because of activity in defense of the Scottsboro boys and her chairmanship of the Blumberg Defense Committee, turned down an offer of a cigarette and continued. “But that’s not the real problem. As a matter of fact, the bankers who are now holding up relief for a million starving workers in this city, could be made to bear the cost of relief by a working class program of taxation.”

Mrs. Burroughs’ candidacy is her first open appearance as a Communist leader since she joined the Communist Party in 1926. For 16 years up to now she taught first and second grade pupils in New York’s schools. At night she read the literature of the labor movement and the theoretical classics of Communism in an effort to understand why the Negro race, of which she is a member, is the most oppressed section of America’s working class.

Joined Party in 1926

“After the war,” said Mrs. Burroughs in her calm class-room voice, matter-of-fact statement summing “I knew enough to want to join something, but I also knew enough not to join the Socialist Party. They had one policy on the Negro question in the South and another, much pinker, policy in the north. It wasn’t really until 1926 that I got into any kind of activity. Then, someone with whom I had gotten in touch so that could I could send my children into a club of juvenile radicals, told me about the Communist Party.”

Since 1926, Mrs. Burroughs has spent her days at P. S. 48 in Queens and her nights in Communist Party activity in Harlem.

Summing Up Her Life History

Her assertion that she belongs to the working class is not the melodramatic campaign avowal. It is a up her life history. Born in Petersburg, Va., she was brought to New York at the age of four by her widowed mother with a sister and a brother. She spent her first seven years in New York in the Colored Or- phan Asylum, which was then at 143d St. and Amsterdam Ave. Her mother not care for children and work in someone’s kitchen at the same time. Besides “sleeping-in” jobs were easiest to find and afforded the best opportunities for saving money. When Williana was 11, her mother took the three children from the asylum and set up housekeeping. By this time her earnings had risen from $5 2 month to $20 and she had a “sleeping-out” job. Williana and her brother went to school and, after school, the girl came to the house where her mother worked to help her with such chores as washing floors, dishes, cleaning the pantry, preparing vegetables.

By the time she was ready to go to the New York City Normal College, which is now known as Hunter College, Williana Burroughs had risen to the position of a paid assistant to her mother. She received $5 a month for waiting on tables. Most of this sum she contributed to the support of her brother and sister. Occasionally she bought books, and less often clothing.

“I guess my mother was pretty disappointed when I dropped from the head of my class,” said Mrs. Burroughs, smiling as if she still regretted it. “But when you had to work, take care of the younger children and find a little time for reading that wasn’t offered in your school courses, it was pretty difficult to stay on top all the time.”

The six-year struggle for a teacher’s education ended triumphantly when Mrs. Burroughs received an appointment as a first grade teacher at a salary of $50 a month.

In late years, although she was known to her fellow-teachers and to parents as a “radical,” her high standing as a teacher and the respect of her associates prevented the Tammany controlled Board of Education from molesting her.

When she became active in the Teachers’ Committee for Defense of Salaries, however, Dr. Ryan, president of the board, and Dr. O’Shea, superintendent of schools, thought they saw an opportunity to get rid of the quiet, forceful little woman, who travelled from Queens to Harlem every night to work for the defense of the Scottsboro boys. The opportunity became ripe after Isidore Blumberg, another teacher, was expelled from the school system after a mock trial, for his chairmanship of the salary committee. Mrs. Burroughs thereupon became chairman of the Blumberg Defense Committee and, with Isidore Begun, led a large delegation of teachers to a Board of Education meeting. The delegation demanded Blumberg’s reinstatement and refused to be silenced by Dr. Ryan’s suave legalisms. Dr. Ryan, unable to prevent the teachers from speaking their minds, called the cops. Subsequently, Mrs. Burroughs and Begun were dismissed for “conduct unbecoming to a teacher and prejudicial to law and order.”

Yesterday Mrs. Burroughs had but one comment to make on the expulsion. “If they thought my conduct I was unbecoming to a teacher then, wait till they see my comptrollership campaign.”

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924. National and City (New York and environs) editions exist.

PDF of original issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1934/v11-n104-may-01-1934-DW-LOC.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1933/v10-n232-sep-27-1933-DW-LOC.pdf