Art Front’s Jerome Klein listens to a two-hour La Corbusier lecture and challenges him in a press conference.

‘Le Corbusier’s Cities in the Sky’ by Jerome Klein from Art Front. Vol. 2 No. 1. December, 1935.

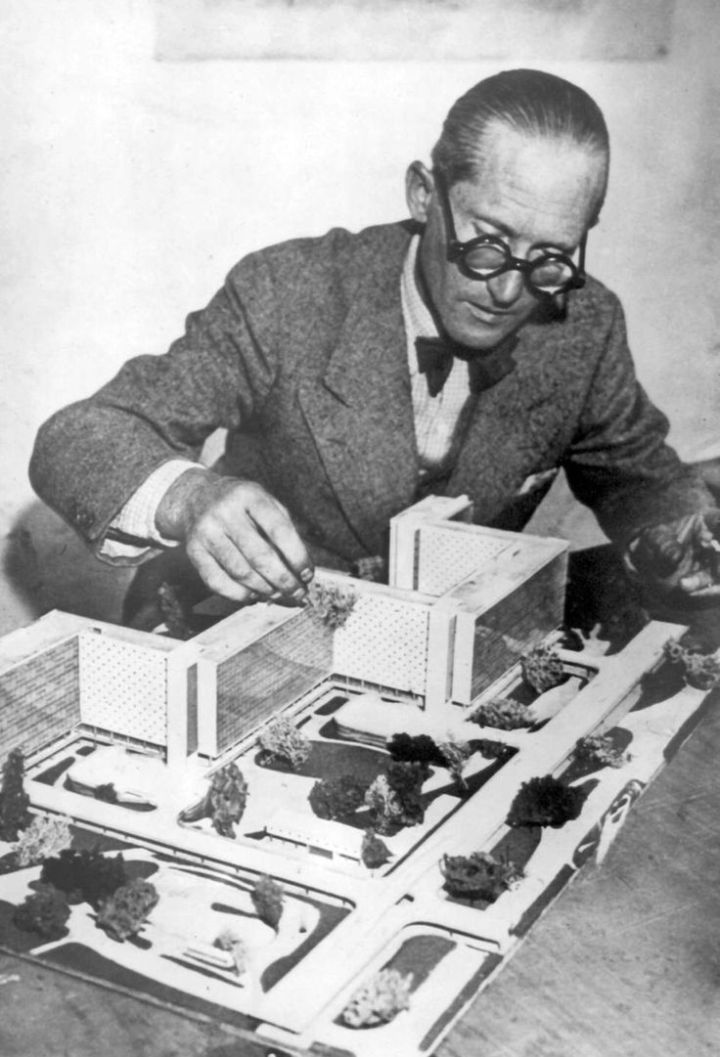

A SELECT audience sat in rapt attention for nearly two hours one evening recently at the Museum of Modern Art, when one of the world’s foremost architects, Le Corbusier, in his first public appearance in the United States, presented a survey of the revolutionary architectural ideas which he has been developing on the printed page and the lecture platform for more than fifteen years.

Mild exclamations of mingled surprise and satisfaction swept the audience when the famous architect set out by contrasting the present typical urban dweller’s day, composed of eight hours’ sleep, eight hours’ work, about four hours spent in transit, etc., and the remaining four hours for leisure, with the disposition of the day to be made in Le Corbusier’s ideal but entirely practicable!-ville radieuse. In the “joyous city” of the architect’s dream, there would be eight hours for sleep, but only five for work and, with transit simplified in a rationally planned community, there would remain a block of fully nine hours for leisure every day!

By the deft manipulation of brightly colored crayons, accompanied by a continuous flow of language quite captivating in its facility, the architect proceeded to define the now familiar points of his program.

Thrusting aside all academic inhibitions and compromises, the revolutionary city-planner would, through utilization of the technical possibilities opened up by the industrial age, replace the dense slums of the Park Avenue, as well as the Second Avenue type, with great skyscraper housing units of steel, glass and concrete, covering only 12 per cent of the ground space, and designed with maximum sunlight and air for all living quarters. Raised on stilts and connected by elevated one-way automobile highways, these widely spaced structures would leave the entire ground space of the city free for pedestrians who would circulate freely under the buildings as well as between them, liberated from the deadly traffic menace of the city of today. The ground between dwelling units would be given over to parks and playgrounds, so that the carefree city dweller would have, only a minute or two from his door, all the outdoor sport and recreational facilities he might desire.

Le Corbusier went on to explain how this entrancing prospect could only be realized by giving due consideration to the peculiarities, topographical, historical, etc., of any city to be rebuilt. He showed how he would renovate Paris without touching the revered cite, how Antwerp’s cathedral would be spared, how the traffic problem of Algiers could best be solved through a superb plan that would clear out all its squalid hovels, etc. The exposition sparkled with such words as “communal” and “collective,” and more especially “order and harmony.”

What was noticeably lacking in the architect’s two-hour barrage of words, drawings, slides and movies, was any reference to the pertinent question, why his blueprints for the ville radieuse, even though worked out in detail for half a dozen specific cases, have always been laid on the shelf? And a second question–what are all the conditions necessary for the realization of his grandiose projects, which amount to nothing less than a wholly new design for living?

Anticipating such a possible “oversight,” I had plied Le Corbusier with questions on these points at a press conference prior to the opening of his lecture series.

What was his purpose in coming here to lecture? Did he entertain serious hopes of seeing his city plans take actual form in the United States?

“Yes, certainly,” and he proceeded to wax lyrical over machinisme and the United States as the “land which has practically created the machine age single- handed. The first era of the machine age, magnificent in its achievements but full of confusion, is now over. There is a new need for order and harmony, which my city plans provide.”

“Yes, but what practical steps are necessary?” I asked.

“Well, laws must be created to free the ground for use.”

“Have you any knowledge of the fate of public housing projects in the United States under the New Deal?”

When he confessed he knew nothing about it, I pointed out that big realty investors and supporting institutions had blocked low-cost housing projects that would have competed with their investments and thus threatened their income. And none of these projects, I insisted, cut so deeply into the network of existing property relations as Le Corbusier’s revolutionary proposals.

“Yes,” he admitted ruefully, “it’s the crisis. Modern civilization is not ready—”

“What do you mean by modern civilization?” I interrupted. ‘Are you referring to capitalist society?”

“No, modern civilization,” he began again—

“Do you mean the capitalist order?” I insisted.

Visibly annoyed, he finally blurted out, “Here are my plans. To me it is indifferent whether they are carried out under Bolshevism or fascism.”

But Le Corbusier did not see fit to go into this problem in his lecture. He was content to put on a brilliant show which wound up in the clouds. And his fashionable audience, after enjoying the high fantasy to the fullest, was able to leave, untroubled by any contact with pressing actualities.

But Le Corbusier is not unaware of the crux of the matter. Who could be in his situation? The man who was once considered a mere eccentric is now recognized in progressive circles the world over as an architect second to none. Here is a man hailed as a genius by a society which is powerless to utilize, except on a small and abortive scale, the fruits of that genius!

Le Corbusier’s dilemma explains his vacillations, causing him to declare about a year ago in an Italian fascist journal that he was the architect not of the future, but of today, though in New York recently he said he was the architect of the future.

Though his urban plans are sound from the engineering standpoint, since they cannot be executed under existing property relations and since they have no bearing on the totally different needs of a classless society which could carry them out, they are, notwithstanding Le Corbusier’s protestations of practicality thoroughly Utopian.

Until he frankly faces the social problem which confronts him, Le Corbusier is condemned to be a prophet uttering a futile cry in the wilderness.

Art Front was published by the Artists Union in New York between November 1934 and December 1937. Its roots were with the Artists Committee of Action formed to defend Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads mural soon to be destroyed by Nelson Rockefeller. Herman Baron, director of the American Contemporary Art gallery, was managing editor in collaboration with the Artists Union in a project largely politically aligned with the Communist Party USA.. An editorial committee of sixteen with eight from each group serving. Those from the Artists Committee of Action were Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Zoltan Hecht, Lionel S. Reiss, Hilda Abel, Harold Baumbach, Abraham Harriton, Rosa Pringle and Jennings Tofel, while those from the Artists Union were Boris Gorelick, Katherine Gridley, Ethel Olenikov, Robert Jonas, Kruckman, Michael Loew, C. Mactarian and Max Spivak.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/cpusa/art-front/v2n01-dec-1935-hi-res-Art-Front-orig.pdf