This wonderful biographical essay and personal appreciation of John Reed by fellow journalist and witness to October, Albert Rhys Williams, was written for the tenth anniversary republication of Reed’s classic ‘Ten Days That Shook The World.’ Transcribed online for the first time here.

‘John Reed’ by Albert Rhys Williams from the Daily Worker Saturday Magazine. Vol. 4 No. 235. October 15, 1927.

The following appreciation of John Reed was written for the Tenth Anniversary Edition of the m

THE first American city in which the longshoremen refused to load war supplies for the Kolchak armies was Portland, on the Pacific Coast. In this city on the 22nd of Oct., 1887, John Reed was born. His father was one of those bluff sturdy pioneers such as Jack London pictures in his tales of the West. A witty man, a hater of shams and hypocrisy. Instead of siding with the rich and powerful he stood against them, and when the trusts like great octopuses got a strangle-hold upon the forests and other natural resources of the state he fought them bitterly. He was persecuted, beaten and ousted from office. But he never capitulated.

Thus from his father John Reed received a goodly inheritance-fighting blood, a first-class brain and a spirit of high courage and daring. His brilliant talents early manifested themselves, and on completing high school he was sent to the most famous university in America–Harvard. Hither the oil kings, coal barons and steel magnates were wont to send their sons. They well knew that after four years spent in sport, luxury and “the passionless pursuit of passionless knowledge,” their sons would come forth with minds altogether freed from any taint of radicalism. Every year in the college and universities tens of thousands. of American youths are thus transformed into defenders of the present order-into White Guards of reaction.

John Reed spent four years inside the walls of Harvard where his personal charm and ability made him a general favorite. He came in daily contact with the young scions of wealth and privilege. He attended the solemn lectures of the orthodox teachers of sociology. He listened to the teachings of the high priests of capitalism–the professors of political economy. Then, like a blow in the face of these learned know-nothings he organized a Socialist Club right in the centre of this stronghold of plutocracy. His elders consoled themselves with the idea that this was only a youthful fancy: “He’ll drop his radicalism,” they said, “as soon as he passes out of the college gates into the world.”

John Reed completed his course, took his degree, went out into the world, and in an incredibly short time, conquered it. Conquered it by his love of life, his enthusiasm and his pen. In the university as editor of the satirical “Lampoon” he had already wielded a facile and brilliant pen. Now there began to pour from it a stream of poems, stories, dramas. Editors competed with one another for his services, magazines began to pay him almost fabulous sums, great newspapers commissioned him to report important affairs in foreign lands.

Thus he became a traveler up and down the highways of the world. Whoever wanted to keep in touch with current events had only to follow John Reed, for wherever anything significant was occurring, there, like a stormy petrel, he was sure to be. In Paterson the textile workers transformed their strike into a revolutionary cyclone-John Reed was in the centre of it.

In Colorado the serfs of Rockefeller crawled out of their trenches and refused to be driven back by the clubs and rifles of the gunmen–John Reed was there with the rebels.

In Mexico the peons raised the banner of revolt and headed by Villa advanced upon the capitol–John Reed on horseback rode forward with them.

The account of this last exploit appeared in “The Metropolitan,” and later in the book “Revolutionary Mexico.” In lyric fashion he pictured the red and purple mountains and the vast deserts “sentinelled by the giant cactus and the Spanish needle.” He was captivated by the great plains. Still more was he captivated by their inhabitants mercilessly exploited by the landlords and the Catholic Church. He shows them driving their herds from the mountain meadows, flocking in to join the armies of liberation, singing around the camp fires at night, and tho cold and hungry, tattered and barefoot, fighting magnificently for land and freedom.

The imperialist world war broke out and John Reed followed the thunder of the guns–in France. Germany, in Italy, in Turkey, in the Balkans and even here in Russia. For his exposure of the treachery of the czar’s “chinovniks” and the collection of material showing their participation in the organization of Jewish pogroms, he was arrested by the gendarmes, together with the famous artist Bordman Robinson. But as always, thanks to some intrigue or miracle of bluff or humor, he wriggled out of their clutches and went laughing on to the next adventure.

Danger never held him back. It was meat and drink to him. He was always penetrating into forbidden zones, into the front-line trenches.

Vivid in my memory is my trip with John Reed and Boris Reinstein to the Riga front in September 1917. Our automobile was going south, toward Wenden, when the German artillery began dropping shells on a little village to the east. At once this village became for John Reed the most interesting spot in the world. He insisted that we go there. Cautiously we crept forward, when suddenly a big shell burst behind us, and the road we had just passed heaved up in the air, a black fountain of smoke and dust. Convulsively we clutched one another in fear, but a minute later, John Reed’s face was shining with delight. Apparently some inner demand of his nature was satisfied.

So he wandered over all the world, into all countries, on all fronts, passing from one high adventure to another. But he was not simply an adventurer, a traveler, a journalist, a spectator from the side-lines, calmly surveying the anguish of human beings. On the contrary, their sufferings were his sufferings. All this chaos, dirt, pain and blood-letting was an insult to his sense of justice and decency. He strove hard to discover the roots of all these evils and then to tear them out by the roots. So back from his journeyings he returned to New York–not for rest, but for new work and agitation. Out of Mexico he returned to declare: Yes, in Mexico there is revolt and chaos, but responsibility for this lies not on the landless peons but on those who foment trouble by supplying gold and weapons -that is, upon the rival American and English oil companies.

Out of Paterson he returned to organize in the biggest hall in New York, in Madison Square Gare den, a grandiose dramatic representation called “the battle of the Paterson proletariat with capital.”

Out of Colorado he returned with the story of the Ludlow Massacre, some of its horrors eclipsing the Lena massacre in Siberia. He related how the mine workers were thrown out of their homes, how they lived in tents, how these tens were kerosene- saturated and set on fire, how the fleeing workers were shot down by soldiers, and how twenty women and children perished in the flames. Turning upon Rockefeller, the king of millionaires, he said: “These are your mines. These are your hired thugs and gunmen. You are the murderer!”

So from the battlefields he returned not with futile chatter about atrocities of the war on one side or the other, but with curses upon war itself as the one great atrocity–a blood-bath organized by the rival imperialisms. In “The Liberator,” a radical revolutionary journal to which without fee he contributed the best of his writings, he published a ferocious anti-militarist article, under the caption: “Get a Tight-jacket Ready for Your Soldier Son.” Along with the other editors he was hauled before the New York courts to be tried for treason. The prosecutor made every effort to obtain a sentence of guilty from the patriotic jury, going so far as to have a band play national hymns near the court while the trial was proceeding. But Reed and his colleagues stood by their convictions. When he boldly declared that he considered it his duty to fight for the social revolution under the revolutionary flag, the prosecutor put the question:

“But in the present war you would fight under the American flag?”

“No!” categorically replied Reed.

“Why not?”

In answer Reed delivered a passionate speech in which he depicted the horrors he had witnessed on the battlefields. So vivid, so heart-moving, that even some of the prejudiced petty bourgeois jurors were moved to tears and the editors were acquitted.

Just as America entered the world war it happened that he underwent an operation removing one of his kidneys. The surgeons declared him unfit for military service.

“The loss of one kidney may exempt me from service in the war between the nations,” he said, “but it won’t exempt me from service in the war between the classes.”

In Russia he discerned the first skirmishes in this great class war and hither he hurried in the summer of 1917.

Swiftly analyzing the situation, he saw that the conquest of power by the proletariat was logical and inevitable. But its delay and postponement troubled him. Every morning he rose and looked out of the door to see whether the revolution had arrived. Each time with something like irritation he found it hadn’t. Finally Smolny gave the signal, and the masses moved forward into the revolutionary struggle. And quite naturally, John Reed moved forward with them. He was everywhere. At the dissolution of the Preparliament, the erection of the barricades, the ovation for Lenin and Zinoviev emerging from underground, the fall of the Winter Palace.

But all this he relates in his book.

His materials he picked up on all sides moving from place to place. He gathered complete files of “Pravda,” “Izvestia,” all proclamations, brochures, placards and posters. He had a particular passion for posters. Whenever a new one appeared and he couldn’t get it any other way, he didn’t hesitate to tear it from the walls.

In those days posters came from the press so thick and fast that it was difficult to find space for them on the hoardings. Cadet, Socialist Revolutionary, Menshevik, Left S.R. and Bolshevik posters were plastered one on top of another. So deep that once Reed ripped off sixteen of them at one pull. Bursting into my room, waving the big paper slab he cried: “Lock! At one sweep I’ve bagged the whole Revolution and Counter-Revolution!”

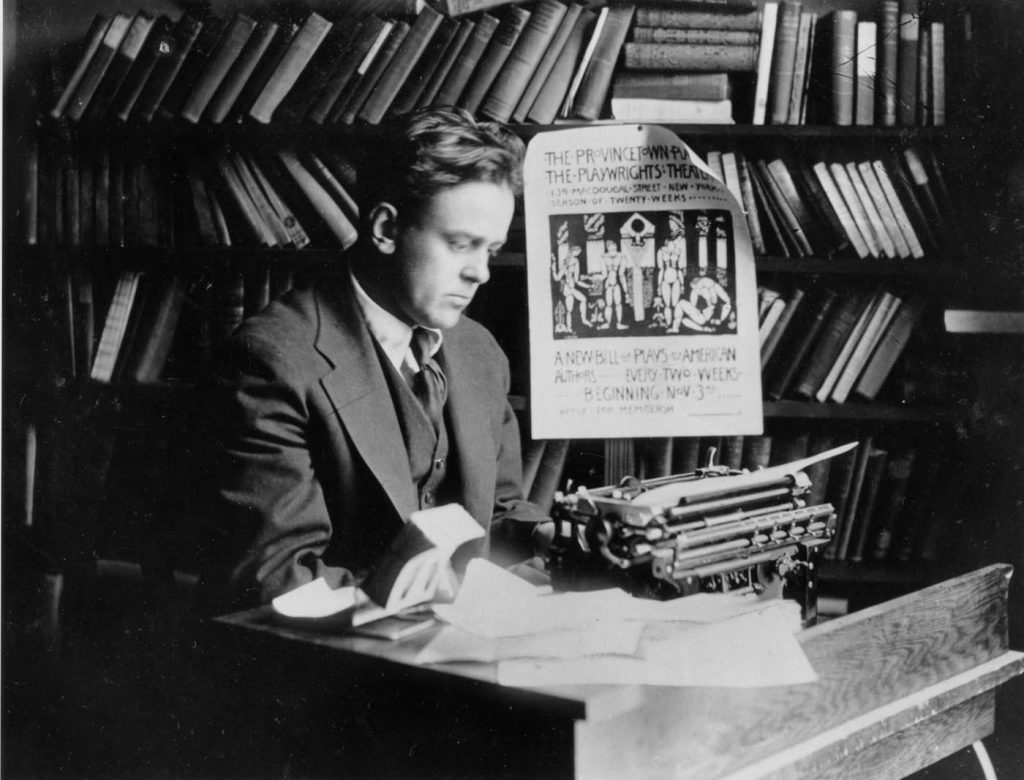

Thus in various ways he gathered together a magnificent collection of materials. So magnificent was it, that when he came to the New York wharf in the Spring of 1918, the agents of the American attorney-general (minister of justice) took it away from him. He succeeded, however, in laying hands on it again and hiding himself with it in a little room in New York, amidst the rattle of the elevated trains rushing by overhead and the roar of the subway trains beneath him, he pounded out on his typewriter “Ten Days That Shook the World.”

The American fascisti of course didn’t want this book to reach the public. Six times they broke into the office of the publishing house, trying to steal it. On his photograph, John Reed wrote, “To my publisher, Horace Liveright, who nearly ruined him- self publishing this book.”

This book was only one product of his literary activities in connection with his propaganda of the truth about Russia. The bourgeoisie, naturally, wanted none of this truth. Hating and fearing the Russian Revolution, they tried to drown it in a flood of lies. An endless stream of dirt and slander poured from the political platforms, the moving picture screen, out of the columns of newspapers and magazines. Magazines that once were begging for his articles, now refused to print a single line he wrote. But they couldn’t close his mouth. He spoke before numberless mass meetings.

He created his own magazine. He became editor of the left wing socialist journal, “The Revolutionary Age,” and afterwards “The Communist.” Article after article he wrote for “The Liberator.” He travelled up and down America, participating in conferences, filling and firing everyone around him with facts, enthusiasm and revolutionary spirit, and finally organizing in the centre of American capitalism the Communist Workers Party–exactly as ten years earlier he organized the Socialist Club in the heart of Harvard University.

The “wise men” as usual had made a mistake. John Reed’s radicalism turned out to be anything but a “passing fancy.” Contrary to prophecies, his contact with the world had not cured him of it. It had only confirmed and buttressed it. How strong and deep that radicalism now was they might find for themselves in reading “The Voice of Labor,” the new Communist organ of which he was editor. The American bourgeoisie now understood that in their country there was a real revolutionist. This very word “revolutionist” now makes them tremble. True in the distant past there were revolutionists in America and even now there are societies enjoying high honor and respect like “The Daughters of the American Revolution,” and “Sons of the American Revolution.” Thus the reactionary bourgeoisie paid tribute to the memory of the revolutionists of 1776. But these revolutionists long ago had passed into the world beyond. John Reed was a live revolutionist, an extraordinarily live one-a challenge to them and a scourge.

One thing only was left for them to do with him- lock him up. So they arrested him–not once or twice, but twenty times. In Philadelphia the police closed the hall refusing to let him speak in it. But he mounted a soap-box and from this rostrum addressed the great crowd that packed the street. So successful a meeting and so many sympathizers that when he was arrested for “violation of order” it was impossible to get a verdict of guilty from the jury. There was hardly an American city that felt altogether right if it hadn’t arrested John Reed at least once. But he always manages to be liberated on bail, or to have his trial postponed and straight- way again took up the battle on some new arena.

The western bourgeoisie acquired the habit of ascribing all its evils and misfortunes to the Russian Revolution. One of the most heinous of its crimes was that it had transformed this talented young American into a flaming fanatical revolutionist. So thought the bourgeoisie. But in reality not quite so. It was not Russia that made John Reed into a revolutionist. From the day of his birth revolutionary American blood flowed in his veins. Yes, though America is always pictured as fat, self-satisfied, capitalist and reactionary, still in its arteries runs rebellion and revolt. Recall the great rebels of the past, Thomas Paine, Walt Whitman, John Brown and Parsons. And John Reed’s comrades and fellow- fighters of today, Bill Haywood, Robert Minor, Ruthenberg and Foster. Remember the industrial wars at Homestead, Pullman, Lawrence and the fighting I.W.W. (Industrial Workers of the World). All these leaders and masses–are of pure American origin. And though at present it is not very evident, still in the blood of Americans runs a strong strain of rebellion.

Consequently, it cannot be said that Russia made a revolutionist out of John Reed. But it did make out of him a scientific thinking and consequential revolutionist. That is its great service, it compelled him to load his desk with the books of Marx, Engels and Lenin. It gave him an understanding of historic processes and the march of events. It compelled him to substitute for his somewhat hazy humanitarian views, the hard rough facts of economics. And it impelled him to become a teacher of the American labor movement and to try to place beneath it the same scientific foundations that he had put under his own convictions.

“But politics are not your forte, Jack!” his friends used to say to him. “You are an artist, not a propagandist. You should devote your talents to creative literary work.” He often felt the force of such words. For in his head always were germinating new poems, novels and dramas, all the time seeking to express themselves, to find form. So when his friends would insist that he should throw aside revolutionary propaganda and sit down to write, he would answer with a smile, “All right, I’ll do so directly.”

But not for a moment did he stop his revolutionary activities. He couldn’t. The Russian Revolution had wrought its spell upon him and possessed him utterly. It had made him its conscript and compelled him to subjugate his wavering anarchistic disposition to the stern discipline of Communism; it sent him like a prophet with a flaming torch throughout the cities of America; it drew him back to Moscow in 1919 to work in the Comintern on the fusion of the two Communist parties.

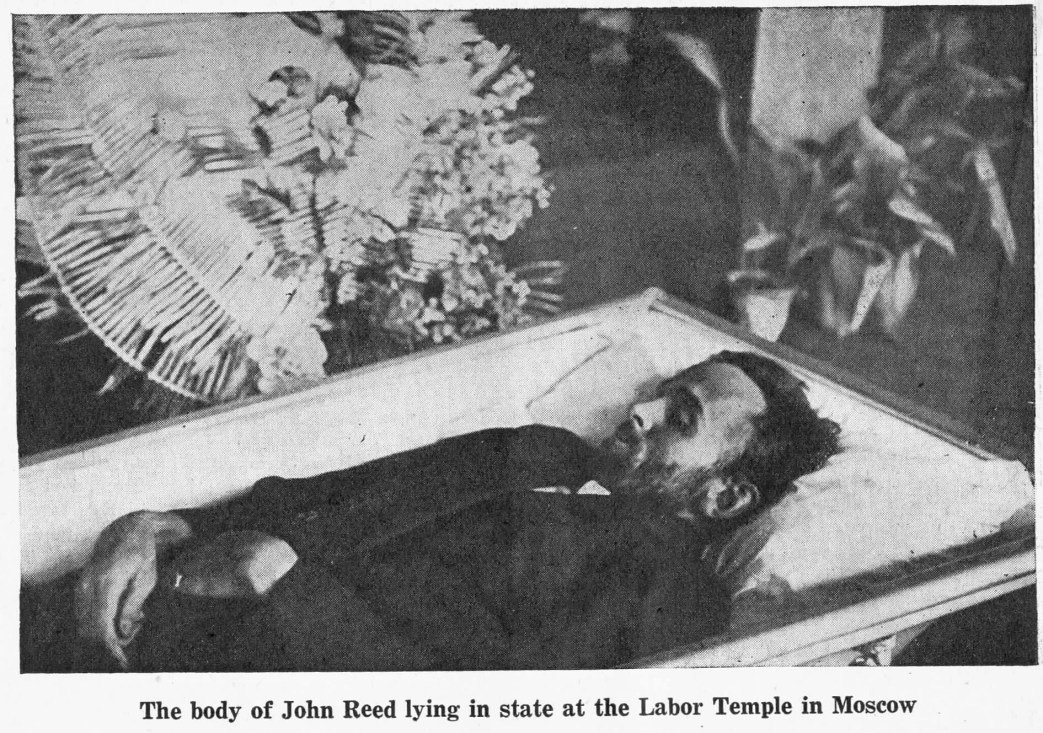

Recharged with new facts and revolutionary theory he set out again on the underground route to New York. Betrayed by a sailor and taken from shipboard, he was thrown into solitary confinement in a Finnish prison. Then back again to Russia; writing in the Communist International; collecting materials for a new book; delegate to the Congress of the Peoples of the East in Baku. Stricken by typhus, probably picked up in the Caucasus, his constitution exhausted by overwork could make no resistance to the disease and on Sunday, October 17th, he died.

Like John Reed there were other warriors who fought against the counter-revolutionary front in America and Europe as gloriously as the Red Army fought against the counter-revolutionary front in the U.S.S.R. Some fell victims of pogroms, others were silenced in prisons. One perished in a storm of the White Sea returning to France. Another in an aeroplane distributing proclamations of protest against intervention was hurled to his death in San Francisco. Ferocious as was the onslaught of imperialism upon the revolution it might have been still more so were it not for these fighters. They did something to hold back the counter-revolutionary assault. Not only Russians, Ukrainians, Tartars, and Caucasians helped to make the Russian Revolution, but to a small extent at any rate, French, German, English and Americans.

Amongst these “non-Russian” figures, John Reed stands out preeminently because he was a man of exceptional abilities, cut down in the very flower of his manhood.

When from Helsingfors and Reval came the first rumors about his death, we thought that these were simply the regular lies fabricated in the course of the daily work of the counter-revolutionary lie-factories. But the announcement was repeated, and when Louise Bryant confirmed it we were compelled in spite of all our hopes to believe it.

Although John Reed died an exile from his own land, and with the sentence of five years imprisonment hanging over his head even the bourgeois press paid their respect to him as an artist and a man. Bourgeois hearts felt a great relief–no longer was there John Reed to expose their falsehood and hypocrisy to chastise them mercilessly with his pen.

The radical world of America suffered an irreparable loss. It is very difficult for comrades living outside America to understand the feeling of bereavement caused by his death. Russians consider it altogether natural, and self-understood that a man should die for his convictions. On this score not a bit of sentimentalism. Here in the Soviet Union thousands and tens of thousands have perished for socialism. But in America such sacrifices have been comparatively few. If you will, John Reed was the first martyr of the Communist Revolution, forerunner of the coming thousands. The sudden ending of his meteoric career in far away blockaded Russia was for American Communists a terrible blow.

One consolation for his old friends and comrades is the fact that John Reed lies in the one place in all the world where he would like to lie on the Red Square, under the Kremlin Wall. Here, as a memorial in harmony with his character is an unhewn granite boulder, on which are chiseled the words:

JOHN REED

Delegate to the III International

1920

The Saturday Supplement, later changed to a Sunday Supplement, of the Daily Worker was a place for longer articles with debate, international focus, literature, and documents presented. The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1927/1927-ny/v04-n235-new-magazine-oct-15-1927-DW-LOC.pdf