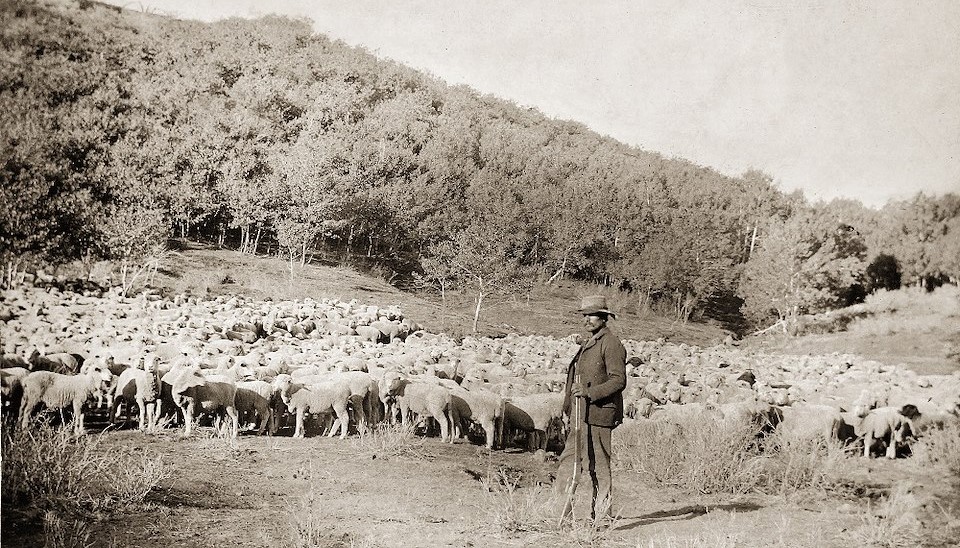

Harrison George, in 1915 a wobbly organizer, discloses the lonely truth of life herding in the highlands.

‘The Sheep-Herder’ by Harrison George from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 16 No. 1. July, 1915.

The Worker Who Makes Your Mutton Chops

AMONG the ancients the tending of the flocks was considered an important and elevated pursuit. The menial drudgery of the fields and the household was delegated to man’s supposed inferior–woman. She was the “hewer of wood and the drawer of water” while the patriarch assumed the lofty duty of caretaker of the herds.

Holy Writ is full of sheep and goats as well as of miracles and murder, all important and profitable pastimes of that period. Even through feudalism the shepherd was held in esteem above the plowman while the poets of the middle ages and later have bequeathed our libraries thousands of verses of nonsense anent the happy, romantic life of the shepherd.

So much so that the modern sheep-herder, no longer the romantic shepherd, in perusing a borrowed book in the shade of a clump of sage brush on the American range today, spits viciously at a tiny sand lizard and mutters much profanity into his tangled whiskers. Lost like the flower’s fragrance “on the desert air.”

Developing capitalism has enlarged the position of the manufacturer and trader above that of the formerly important sheep grower, etc., he losing in social estimation in direct proportion to his lessening economic importance. Also on this continent the ever narrowing area of free range land and the increasing amount of capital necessary to enter the field have, altogether, divorced the herder from the ownership of the sheep he herds and from the romance of his calling.

He is now a common wage slave with a dirty, lonesome job, and all the poems ever written cannot prevail against his discontent that ebbs and flows with the distracting, incessant “baa-baa-baa” chorus of three thousand dusty, stinking “woolies.”

Not many years back the sheep men and the cattle men fought desperate battles for range rights all over the west. Many a sheep-herder in those days bedded down his band at sunset and rolled up in his blankets not knowing but that during the night a volley of lead would finish him while the band would be slaughtered and stampeded over a cliff with yells and shots from the cattle raiders. Strenuous times for the sheep-herder, resulting in a commensurate wage scale, as not all men were willing to take the risk. But today it is more peaceable, as the conflicting forces have established separate ranges with deadlines over which no sheep must pass.

In recent years broken-down professors of algebra and Greek, consumptive clerks. and fugitives from factory life, all having in mind the beautiful verses of the poets, have come west to compete with illiterate Europeans and Mexicans in herding sheep. This is, of course, readily reflected in the paycheck. Where in past years the scale ran from sixty to seventy-five dollars per month, it is now from thirty to fifty dollars. Both with “grub” furnished.

As a result of low pay the herder slackens care of the band. In charge of approximately fifteen thousand dollars’ worth of property, many herders will lose from eight to twelve per cent where during years of higher pay herders lost only from two to six per cent of the sheep. Now if a couple of “woolies” get into quicksand or mire the herder complacently walks on; if a coyote wants mutton some night he will not leave his blankets to interfere nor quit his camp-fire to round up the band in a blizzard. Why should he trouble himself and risk freezing for his boss’s profits?

The herder is always on duty. With care of the band constantly in mind he must turn out at daybreak and cook his own flap-jacks, sow-belly and coffee over the sage brush camp-fire. Often he has no noon meal, sometimes munching a bacon sandwich carried in his pocket since the dawn, as he wearily follows the band through the desolate hills. At sun-down after watering and bedding down the band, he must prepare supper. A monotonous diet of canned goods, salt meat and prunes garnished with dirt and flies and devoured in silence. At night his dogs keep watch as he courts Morpheus and fights mosquitoes under his dusty tarpaulin, jumping up at call of the dogs to fight off the sheep-killing coyotes with an ever-handy Winchester.

Alternately subject to the extremes of heat and cold of the high deserts, he ranges in summer far into the mountain fastnesses, coming down with the snow which covers the shorter grasses; while in the winter he herds near the home ranch, to which he drives the band with all speed should a blizzard set in, hay being kept at the ranch to save the sheep from starvation when deep snow covers the range land.

Living a miserable, lonely existence, visited only by the camp tender bringing supplies, under-paid, ill-fed, un-housed, un-kempt of beard and clothing, this de-socialized being is enviously gazed at from car window and tourist auto by many an eastern “dude” seeking romance and ad- venture in the great west.

Perhaps the reader may have seen from a car window as the train rushed swiftly through the Rocky Mountain region peculiar piles of flat rocks standing sentinel-like atop of butte and canyon rim watching over the solitudes. These are “sheep-monuments,” piled up by the herder to guide him in the vasty deserts where fogs and blizzards confuse and distance to water must be kept in mind.

An exile from social life for months on end, the sheep-herder is prone to excessive dissipation when he hits the western towns. where smug-faced merchants compete with saloon and brothel to fleece him. This same merchant coolly sends him to jail when his wad is gone and he asks “two bits” for a meal.

Insanity and a peculiar mental stupor afflict many herders while the “spotted fever” carried by the bites of sage-ticks means almost certain death. Mental troubles result perhaps from loneliness and sexual perversion with minor causes, although herders stoutly contend that factory made blankets so scantily measured that they compel the sleeper to get up fifty times a night to turn them about trying to find the long way, plays an important part. This does not appear humorous to them either.

As a social unit he is anathematized and he and his job sneeringly referred to as being as low as a man can get. All told his social and economic treatment is resulting in a nascently rebellious frame of mind. What he may do, this dusty proletarian of the west, is an open question. His position precludes initiative action in the war of the classes. But without a doubt he will stand by his class if put to trial.

There is an ancient legend of some shepherds’ gladness on the hills of Palestine when they saw a brilliant star that was said to token the arrival of a Messiah, and I can truthfully say it is no myth that thousands of sheep herding workers in the west today will eagerly welcome the star that rises out of the east, the star that hails the coming of a real and material Messiah-SCIENTIFIC SOCIALISM-THE HOPE OF THE WORLD.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v16n01-jul-1915-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf