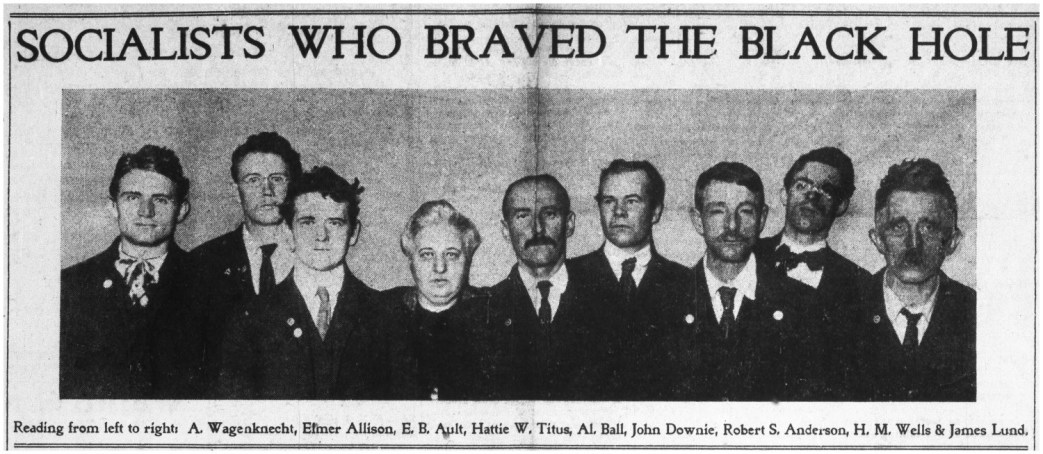

Just marvelous. For all of us ever arrested at a demonstration, let Alfred Wagenknecht remind you of the joys of that experience with these vignettes of insurgent Seattle Socialists fighting for free speech in 1907 and ending packed in a filthy cell. Interestingly, half the activists pictured here, including Wagenknecht, would be founding Communists a decade later. Great stuff.

‘The Black Hole of Seattle: How it Happened’ by Alfred Wagenknecht from The Socialist (Seattle). Vol. 8 No. 350. November 2, 1907.

It is 7:30 Monday evening October 28, and we are off. The market place is black with people and umbrellas, for it is raining hard. No less than 1500 are present to witness the arrest of Socialist street speakers. The meeting has been well advertised.

John Downie, state chairman, has mounted the box which has been placed in an entirely unused section of the Market Place. The crowd cheered. He told them of the arranged parade to the city council chamber.

Downie is arrested and Robt. Anderson, “The Socialist” newsboy, mounted the box. He announced the Labor Temple meeting for Sunday, Nov. 3. Said he was glad to see so many people who believed in free speech. (Immense applause.) He then asked all not to forget the parade to the city council and was arrested.

James Lund of Redondo, Washington was next. He was dressed for the occasion. He knew the jail was filthy from a previous experience. He asked the audience not to forget to parade to the council chamber and he started on his trip to jail.

E.T. Allison, secretary of Local Bangor, Wash., was next in line. He announced the Labor Temple meeting. He was then accommodated with his first auto ride in the police patrol.

A.G. Ball, member of Local Portland, Ore., then tried to exercise the right of free speech. “Workingmen, Working women and Parasites,” said Ball. That’s all. He followed the others.

E.B. Ault jumped on the box, cried out against the outrage, jumped from the box in the hands of an officer.

H.M. Wells, a Seattle Socialist, lawyer, recently admitted to the Seattle bar, came next. The crowd was reminded by him about the parade to the council chamber and announced that a woman would be the next speaker. And he was arrested, as was expected.

Mrs. Titus is on the box. She asks if her hat is on straight and is assured that it is. She then talks of the Revolution of ‘76. The officers seem timid in placing her under arrest. She said a word or two about our Revolution. That seemed to settle it. Officers were afterward heard denouncing the officer delegated to arrest Mrs. Titus for his hesitation.

The immense crowd commenced moving toward First Avenue. Calls were heard on every hand reminding us of the trip of the council.

A Wagenknecht, while walking towards the City Hall, was arrested for asking people to parade to the council, and was placed in the police auto. Wm. Nietman, a Seattle Socialist, called out “Goodbye Wagenknecht” and was promptly saved further pains at parting. He went with Wagenknecht to police headquarters.

We are all here in one cell, except Mrs. Titus who occupies the cell to the left and Robert Anderson the one to the right. We walk the floor and tell our several stories. All are good natured.

The air is getting unbearable. There are 19 men now in this cell, hardly room enough for all of us to lie down, conceding that we do not care to lie in a mixture of water, etc., nor too close to one “crummy” man, three drunks nor one individual who takes a particular liking to vomiting. He vomits because he wants to. He drinks a cup of water and then sticks his fist down his throat, holds down his head and lets it run out again. He does not always hit the toilet bowl either, and as a result, he makes tracks of his vomit in his walk around the cell. Spitting on the floor of the cell is being strenuously objected to and some are kicking against smoking.

The jailer is heard. We kick against the cell door and demand fresh air. Many of us are in our shirts with suspenders off of shoulders. Shoes are being taken off. We are beginning to sweat. The jailer hears us. He opens the door and demands to know who wants fresh air. We all want fresh air. He commands us to come with him. We put on our clothes and shoes and follow, all except the dead drunks. Even the man with the vomit habit stays with us. We would much rather have left him behind. He has vomited eleven times since our imprisonment.

We go down two flights of stairs and are shoved into a big iron cage about 18 by 12 feet. One man is already here. There are 14 of us altogether. The air is damp and we feel chilled. The cage is divided into three parts. Two cells with four sheet iron bunks each and a corridor.

The drunks are using the toilet bowl. It does not flush. The chill, damp air becomes foul. The bunks are covered with dust one fourth inch deep.

The vomit fiend has obliged us with three more vomits. The last one hit the floor only. The corridor floor of the cage becomes slimy.

Everybody is cold. The jailer who handed us the gold brick has appeared several times and was made the recipient of scathing denunciation by the Socialists and unchoice language by the drunks. The jailer remarks that what we wanted was fresh air.

It is morning. Daylight is visible. The trustees are beginning their work. We ask them as they pass if they are Socialists. We tell one of the condition of the toilet bowl. He crawls upon the cage and it seems to us as if he were pouring water down a funnel into a pipe that leads to the bowl. The bowl leaks at the bottom. The wash is running all over the floor.

We are getting wet feet. The chain gang passes. We ask them all if they are Socialists. We see them shackled.

Our remarks are caustic and can be heard by the chain gang and guards.

Jailer again appears and pities us.

Says we have been misled. We tell him to keep his pity and bring us ham sandwiches. Trustees appear with breakfast. A sumptuous repast. Dirty coffee and a half loaf of stale bread each. The coffee is hot and we drink it to get warm. We tell trustees to take bread to Wappy with our respects.

Ault uses a loaf of bread for a pillow. Says it serves.

Downie is so mad he can’t sleep. Wells adapts himself to his environment and dozes. Lund, who was a sailor, talks with the sailor drunk. Allison philosophizes, on stink. Ball is kept busy telling us the time. He smuggled in his watch. We all smuggled in one thing and another. The Communist Manifesto, “No Compromise,” “Socialism Utopian and Scientific,” papers and pencils; all with us.

The trustees return and gather the tin cups and left-over bread. One trustee dumps the left-over coffee in toilet bowl and he hits the cups against the inside of the bowl to empty them.

A new jailer appears. We demand to be transferred to a dryer and warmer cell. Our arguments are heeded. We again find ourselves in our former cell. The Socialists are occupying the best corners.

Our vomiter is just in the midst of his sixteenth performance. The Head drunk is brought whiskey by the jailer. He is sick from whiskey and needs more. Jailer says he feels sure we don’t drink. We admit we don’t.

Jailer calls out the State Organizer. Times reporter wants to take our pictures. We all consent and it is done.

We hear the Marseillaise sung in French in the women’s cell, Nietman and some others of us sang it in German in the cage below.

Everybody is walking, anxious for trial. The door opens. The Socialists are called out one by one. We are marched to the police clerk’s window. We are met by comrades who tell us we are free. The trial has been postponed. We walk up Third avenue. We all breathe deeply of the good fresh air. We eat, we wash. We are ready for another skirmish with capital’s hirelings.

There have been a number of journals in our history named ‘The Socialist’. This Socialist was a printed and edited in Seattle, Washington (with sojourns in Caldwell, Idaho and Toledo, Ohio) by the radical medical doctor, former Baptist minister and socialist, Hermon Titus. The weekly paper began to support Eugene Debs 1900 Presidential run and continued until 1910. The paper became a fairly widely read organ of the national Socialist Party and while it was active, was a leading voice of the Party’s Left Wing. The paper was the source of many fights between the right and left of the Seattle Socialist Party. in 1909, the paper’s associates split with the SP to briefly form the Wage Workers Party in which future Communist Party leader William Z Foster was a central actor. That organization soon perished with many of its activists joining the vibrant Northwest IWW of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/thesocialist-seattle/071102-seattlesocialist-v08n350.pdf