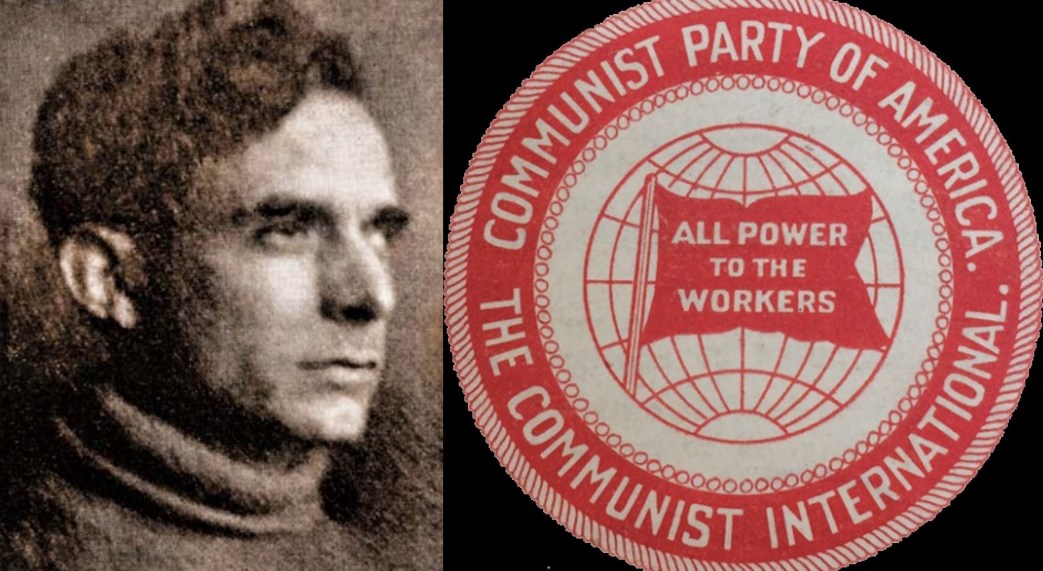

An essential document of our movement. Louis C. Fraina was elected International Secretary of the Communist Party of America, one of four parties seeking admittance into the newly formed Communist International, and its founding convention. Written shortly after the September, 1919 splits, Fraina gives a valuable history of the revolutionary movement in the U.S., the struggle between Left and Right within the Socialist Party that exploded in the war and Russian Revolution, as well as surveying the larger political scene, and making an appeal for the C.P.A. to be recognized as the U.S. section. The Comintern’s response was for the U.S. comrades to unify.

‘Report and Application for Membership in the Communist International on Behalf of the Communist Party of America’ by Louis C. Fraina from The Communist. Vol. 1 No. 3. October 11, 1919.

Chicago, Illinois. November 24th, 1919.

To the Bureau of the Communist International.

Comrades:—

As International Secretary, I make application for admission of the Communist Party of America to the Bureau of the Communist International as a major party.

The Communist Party, organized September 1, 1919, with approximately 55,000 members, issues directly out of a split in the old Socialist Party. The new party represents more than half the membership of the old party.

1. SOCIALIST PARTY, SOCIALIST LABOR PARTY, IWW

The Socialist Party was organized in 1901, of a merger of two elements: 1. Seceeders from the Socialist Labor Party, like Morris Hillquit, who split away in 1899 largely because of the SLP’s uncompromising endeavors to revolutionize the trades unions; 2. The Social Democratic Party of Wisconsin, a purely middle-class liberal party tinged with socialism, of which Victor L. Berger was representative.

The Socialist Labor Party, organized definitely in 1890, acted on the basis of the uncompromising proletarian class struggle. Appearing at a period when class relations were still in state of flux, when the ideology of independence, created by the free lands of the West, still persisted among the workers, the Socialist Labor Party emphasized the class struggle and the class character of the proletarian movement. Realizing the peculiar problems of the American movement, the Socialist Labor Party initiated a consistent campaign for revolutionary unionism and against the dominant craft unionism of the American Federation of Labor, which, representing the skilled workers — “aristocracy of labor” — sabotaged every radical impulse of the working class. The SLP was a party of revolutionary socialism, against which opportunist elements revolted.

The Spanish-American War was an immature expression of American imperialism, initiated by the requirements of monopolistic capitalism. A movement of protest developed in the middle class, which, uniting with the previous impulses of petty bourgeois and agrarian radicalism, expressed itself in a campaign of anti-imperialism. There was a general revival of the ideology of liberal democracy. The Socialist Party expressed one phase of this liberal development; it adopted fundamentally a non-class policy, directing its appeal to the middle class, to the farmers, to every temporary sentiment of discontent, for a program of government ownership of the trusts. The Socialist Party, particularly, discouraged all action for revolutionary unionism, becoming a bulwark of the Gomperized AF of L and its reactionary officials, “the labor lieutenants of the capitalist class.” This typical party of opportunist socialism considered strikes and unions as of minor and transitory importance, instead of developing their revolutionary implications; parliamentarism was considered the important thing, legislative reforms and the use of the bourgeois state the means equally for waging the class struggle and for establishing the Socialist Republic. The Socialist Party was essentially a party of State Capitalism, an expression of the dominant moderate socialism of the old International.

But industrial concentration proceeded feverishly, developing monopoly and the typical conditions of imperialism. Congress — parliamentarism — assumed an aspect of futility as imperialism developed and the federal government became a centralized authority. The industrial proletariat, expropriated of skill by the machine process and concentrated in the basic industries, initiated new means of struggle. The general conditions of imperialistic capitalism developed new tactical concepts — mass action in Europe and industrial unionism in the United States, the necessity for extraparliamentary means to conquer the power of the state.

The old craft unionism was more and more incapable of struggling successfully against concentrated capitalism. Out of this general situation arose the Industrial Workers of the World, organized in 1905 —an event of the greatest revolutionary importance. The IWW indicated craft unionism as reactionary and not in accord with the concentration of industry, which wipes out differences of skill and craft. The IWW urged industrial unionism, that is to say, a unionism organized according to industrial division; all workers in one industry, regardless of particular crafts, to unite in one union; and all industrial unions to unite in the general organization, thereby paralleling the industrial structure of modern capitalism. Industrial unionism was urged not simply for the immediate struggle of the workers, but as the revolutionary means for the workers to assume control of industry.

Previous movements of revolutionary unionism, such as the Socialist Trades and Labor Alliance and the American Labor Union, united in the IWW. The Socialist Labor Party was a vital factor in the organization of the IWW, Daniel DeLeon formulating the theoretical concepts of industrial unionism. Industrial unionism and the conception of overthrowing the parliamentary state, substituting it with an industrial administration based upon the industrial unions, was related by DeLeon to the general theory of Marxism.

The Socialist Party repeatedly rejected resolutions endorsing the IWW and industrial unionism, although supporting IWW strikes by money and publicity. The Socialist Party supported the AF of L and craft unionism, rejection the revolutionary implications of industrial unionism — the necessity of extraparliamentary action to conquer the power of the state.

After the panic of 1907 there was an awakening of the American proletariat. New and more proletarian elements joined the Socialist Party. Industrial unionism developed an enormous impetus, and violent tactical disputes arose in the party, particularly in the Northwest, where the new unionism was a vital factor. These disputes came to a climax at the Socialist Party Convention of 1912. The tactical issue of industrial unionism was comprised of the problem of whether parliamentarism alone constituted political action, whether parliamentarism alone could accomplish the revolution, or whether extraparliamentary means were indispensable from the conquest of political power. The Socialist Party convention, by a large majority, emasculated the Marxian conception of political action, limiting it to parliamentarism; an amendment to the party constitution defined political action as “participation in elections for public office and practical legislative and administrative work along the lines of the Socialist Party platform.” That year the Socialist Party, by means of a petty bourgeois liberal campaign, polled more than 900,000 votes for its presidential candidate; but thousands of militant proletarians seceded from the party in disgust at the rejection of revolutionary industrial unionism, while William D. Haywood, representative of the industrialists in the party, was recalled on referendum vote as a member of the National Executive Committee.

The organization of the Progressive Party in 1912 made “progressivism” a political issue. The Socialist Party adapted itself to this “progressivism.” But this progressivism was the last flickering expression of radical democracy; Theodore Roosevelt harnessed progressivism to imperialism and State Capitalism. A new social alignment arose, requiring new socialist tactics.

2. THE WAR, THE SOCIALIST PARTY, AND THE BOLSHEVIK REVOLUTION

After 1912, the party officially proceeded on its peaceful petty bourgeois way. Then — the war, and the collapse of the International. The official representatives of the Socialist Party either justified the betrayal of socialism in Europe, or else were acquiescently silent, while issuing liberal appeals to “humanity.”

As the war continued and the betrayal of socialism became more apparent, and particularly as the American comrades learned of the revolutionary minority elements in the European movement, there was a revolutionary awakening in the Socialist Party, strengthened by new accessions of proletarian elements to the party. The first organized expression of this awakening was the formation of the Socialist Propaganda League in Boston in 1916, issuing a weekly organ which afterwards became The New International, with Louis C. Fraina as Editor and S.J. Rutgers as Associate. The League emphasized the necessity of new proletarian tactics in the epoch of imperialism. In April 1917 was started The Class Struggle, a magazine devoted to international socialism. In the state of Michigan, the anti-reformists captured the Socialist Party and carried on a non-reformist agitation, particularly in The Proletarian.

The enormous exports of war munitions, the development of large reserves of surplus capital, and the assumption of a position of world power financially by American capitalism forced the United States into the war. There was an immediate revolutionary upsurge in the Socialist Party. The St. Louis Convention of the party, in April 1917, adopted a militant declaration against the war, forced upon a reluctant bureaucracy by the revolutionary membership. But this bureaucracy sabotaged the declaration. It adopted a policy of petty bourgeois pacifism, uniting with the liberal People’s Council, which subsequently accepted President Wilson’s “14 Points” as its own program. Moreover, there was a minority on the National Executive Committee in favor of the war; in August 1918, the vote in the NEC stood 4 to 4 on repudiation of the St. Louis Declaration. The Socialist Party’s only representative in Congress, Meyer London, openly supported the war and flouted the party’s declaration against the war; but he was neither disciplined nor expelled — in fact, secured a renomination. Morris Hillquit accepted the declaration against the war, but converted it into bourgeois pacifism, being a prominent member of the People’s Council. In reply to a question whether, if a Member of Congress, he would have voted in favor of war, Hillquit answered (The New Republic, December 1, 1917): “If I had believed that our participation would shorten the World War and force a better, more democratic, and more durable peace I should have favored the measure, regardless of the cost and sacrifices of America. My opposition to our entry into the war was based upon the conviction that it would prolong the disastrous conflict without compensating gains to humanity.” This was a complete abandonment of the class struggle and the socialist conception of war. The war was a test of the Socialist Party and proved it officially a party of vicious centrism.

The Russian Revolution was another test of the party. Officially, the Socialist Party was for the Menshevik policy and enthusiastic about Kerensky; while the New York Call, Socialist Party daily newspaper in New York City, editorially characterized Comrade Lenin and the Bolsheviki in June 1917 as “anarchists. ”The party officially was silent about the November Revolution; it was silent about the Soviet government’s proposal for an armistice on all fronts, although the National Executive Committee of the party met in December and should have acted vigorously, mobilizing the party for the armistice. But the revolutionary membership responded, its enthusiasm for the Bolshevik Revolution being magnificent. This enthusiasm forced the party representatives to speak in favor of the Bolsheviki, but always in general terms capable of “interpretation.” After the Brest-Litovsk peace, there was a sentiment among the party representatives for war against Germany “to save the Russian Revolution.” The Socialist Party carried on an active campaign against intervention in Russia. However, this campaign did not emphasize the revolutionary implications of the situation in Russia, as making mandatory the reconstruction of the socialist movement. A campaign against intervention must proceed as a phase of the general campaign to develop revolutionary proletarian action.

3. THE LEFT WING DEVELOPS

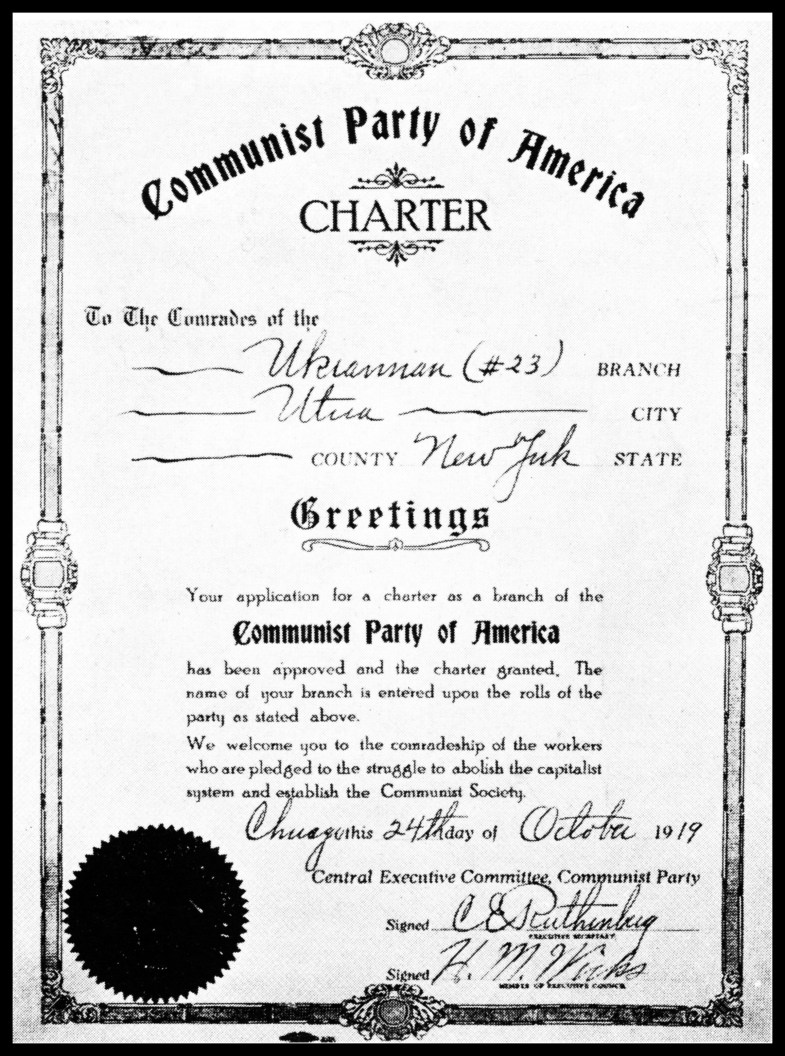

During 1918, the Socialist Party was in ferment. The membership was more and more coming to think in revolutionary terms. Then came the armistice and the German Revolution. The response was immediate. On November 7, 1918, a Communist Propaganda League was organized in Chicago. On November 9, Local Boston, Socialist Party, started to issue an agitational paper, The Revolutionary Age. This paper immediately issued a call to the party for the adoption of revolutionary Communist tactics, emphasizing that the emergence of the proletariat into the epoch of the world revolution made absolutely imperative the reconstruction of socialism. In New York City, in February 1919, there was organized the Left Wing Section of the Socialist Party. Its Left Wing Manifesto and Program was adopted by Local after Local of the Socialist Party, the Left Wing acquiring a definite expression. The Left Wing secured the immediate adhesion of the Lettish, Russian, Lithuanian, Polish, Ukrainian, South Slavic, Hungarian, and Estonian Federations of the party, representing about 25,000 members. The official organs of the Federations did splendid work for the Left Wing.

In January 1919, the National Executive Committee of the Socialist Party decided to send delegates to the Berne Congress of the Great Betrayal. This action was characteristic of the Social Patriot and centrist bent of the party administration. There was an immediate protest from the membership, the Left Wing using the Berne Congress as again emphasizing the necessity for the revolutionary reconstruction of socialism. In March we receive a copy of the call issued by the Communist Party of Russia for an international congress to organize a new International. The Revolutionary Age was the first to print the call, yielding it immediate adhesion; while the Left Wing Section of New York City transmitted credentials to S.J. Rutgers to represent it at the Congress. Local Boston initiated a motion for a referendum to affiliate the party with the Third International; this was thrown out by the national administration of the party on a technicality; but after much delay another local succeeded in securing a referendum. (The vote was overwhelmingly in favor of the Third International.)

The Left Wing was now, although still without a definite organization, a formidable power in the Socialist Party. Previously all revolts in the party were isolated or consisted purely of theoretical criticism; now there was this theoretical criticism united with a developing organizational expression. There was not, as yet, any general conception of the organization of a new party; it was a struggle for power within the Socialist Party.

About this time the call for the new Socialist Party elections was issued. The Left Wing decided upon its own candidates. The elections constituted an overwhelming victory for the Left Wing. The national administration of the Socialist Party, realizing impending disaster, decided upon desperate measures. Branch after Branch and Local after Local of the party, which had adopted the Left Wing Manifesto and Program, was expelled. Morris Hillquit issued a declaration that the breach in the party had become irreconcilable, and that the only solution was to split, each faction organizing its own party. At first the expulsions were on a small scale; then, the danger becoming more acute, the national administration of the party acted. The National Executive Committee met in May determined to “purge” the party of the Left Wing. The NEC was brutal and direct in its means; it refused to recognize the results of the elections, declaring them illegal because of “frauds.” It issued a call for an Emergency National Convention on August 30, which was to decide the validity of the elections, meanwhile appointing an “Investigating Committee.” But in order to insure that the convention would “act right,” the NEC suspended from the party the Russian, Ukrainian, Polish, Hungarian, South Slavic, Lettish, and Lithuanian Federations, and the Socialist Party of Michigan state. In all, the NEC suspended 40,000 members from the party — a deliberate, brazen move to control the election of delegates to the convention.

The charge of “fraud” was an easily detected camouflage. The elections were so overwhelmingly in favor of the Left Wing candidates as to prove the charge of fraud itself a fraud. For International Delegates the vote was (excluding three states, where the returns were suppressed, but which would not alter the results): Left Wing candidates — John Reed, 17,235; Louis C. Fraina, 14, 124; C.E. Ruthenberg, 10,773; A. Wagenknecht, 10,650; I.E. Ferguson, 6,490. Right Wing candidates — Victor L. Berger, 4,871; Seymour Stedman, 4,729; Adolph Germer, 4,622; Oscar Ameringer, 3,184; J.L. Engdahl, 3,510; John M. Work, 2,664; A.I. Shiplacoff, 2,346; James Oneal 1,895; Algernon Lee, 1,858. Louis B. Boudin, who was pro-war and against the Bolshevik Revolution, secured 1,537 votes. The Left Wing elected 12 out of 15 members of the National Executive Committee. The moderates who had been dominant in the Socialist Party were overwhelmingly repudiated. Kate Richards O’Hare (supported by the Left Wing, although not its candidate) defeated Hillquit for International Secretary, 13,262 to 4,775.

The NEC, after these desperate acts and after refusing to make public the vote on the referendum to affiliate with the Communist International, decided to retain office until the convention of August 30, although constitutionally it should have retired on June 30.

The issue was now definite. No compromise was conceivable. Events were directly making for a split and the organization of a new party. The Old Guard was concerned with retaining control of the Socialist Party organization, even if minus the bulk of the membership; the Left Wing was concerned with the principles and tactics.

4. THE NATIONAL LEFT WING CONFERENCE AND AFTER

Just prior to the session of the National Executive Committee, Local Boston, Local Cleveland, and the Left Wing Section of the Socialist Party of New York City, issued a call for a National Left Wing Conference, which met in New York City on June 21. The Conference was composed of 94 delegates representing 20 states, and coming overwhelmingly from the large industrial centers, the heart of the militant proletarian movement.

There was a difference of opinion in the Conference as to whether a Communist Party should be organized immediately, or whether the struggle should be carried on within the Socialist Party until the Emergency Convention August 30. The proposal to organized a new party immediately was defeated, 55 to 38. Thereupon 31 delegates, consisting mostly of the Federation comrades and the delegates of the Socialist Party of Michigan, determined to withdraw from the Conference. The majority in the Conference decided to participate in the Socialist Party Emergency Convention, all expelled and suspended Locals to send contesting delegates; but issued a call for a convention September 1 “of all revolutionary elements” to organize a Communist Party together with delegates seceding from the Socialist Party Convention.

One important thing was accomplished by the Left Wing Conference — it made definite the issue of a new party, which until that moment was very indefinite. The minority in the Conference emphasized the inexorable necessity for the organization of a new party. This was in the minds of practically all, but it now became a definite conviction. There were centrists in the Conference who still felt that the old party could be captured, who recoiled from a split; and these voted with the majority to go to the Socialist Party Convention; but the majority in the majority was convinced of the necessity for a new party, differing with the minority of 31 simply on the right procedure to pursue.

After the Conference, the minority of 31 issued a call for a convention on September 1 to organize a Communist Party, repudiating all participation in the Socialist Party Convention.

In the course of its development the Left Wing, while Communist in its impulse, had attracted elements not all Communist. There were conscious centrists; comrades who had for years been waging a struggle for administrative control of the party; and comrades who were disgusted with the gangster tactics pursued by the Old Guard in control of the party administration. The situation now began to clarify itself — Right Wing, Center, Left Wing.

The important factor in this situation was the division in the organized Left Wing — the National Council, elected by the Left Wing Conference, and the minority which had organized a National Organization Committee and issued its own call for a Communist Party Convention. This constituted more than a split in the Left Wing; it was a split of the conscious Communist elements in the Left Wing. This division, if persisted in, meant disaster. Unity was necessary —not simply organizational unity, which at particular moments must be dispensed with, but revolutionary unity. This unity was accomplished by agreement for the merger of the two factions on the basis of a Joint Call for a Communist Party Convention on September 1.

The overwhelming majority of the organizations and delegates represented at the Left Wing Conference accepted the Joint Call.

The Left Wing had found itself, unified itself, determined upon the organization of a real Communist Party.

5. THE CONVENTIONS AND REVOLUTIONARY RECONSTRUCTION

The Socialist Party Convention met on August 30th. The repudiated National Executive Committee manipulated the roster of delegates to insure Right Wing control, dozens of delegates suspected of sympathy for the Left Wing being contested and refused admission to the convention. The police were used against these delegates — an indication of the potential Noske-Scheidemann character of the Old Guard of the Socialist Party. The Left Wing was stigmatized as anarchistic, as consisting of foreigners, as an expression of emotional hysteria. The Socialist Party Convention was ruthlessly dominated by the Right Wing, which used the camouflage of greetings to Soviet Russia and words about the “Revolution.” It did not adopt a new program in accord with the new tactical requirements of socialism, avoiding all fundamental problems. The Socialist Party Convention adopted a resolution calling for an “International Congress” to organize the “Third International,” to include the Communist Party of Russia and of Germany, but ignoring the existing Communist International! A minority resolution to affiliate with the Communist International was decisively defeated. The two resolutions were submitted to referendum vote. (There is a group still in the Socialist Party styling itself “Left Wing” which is unscrupulously trying to garner sentiment for the Communist International to revitalize the old party.) The Socialist Party now represents about 25,000 members.

The delegates refused admission to the Socialist Party Convention proceeded to organize their own convention, the first act of which was to proclaim itself the “legal convention” of the Socialist Party — a beautiful centrist twist! These delegates organized themselves as the Communist Labor Party. This was on Sunday, Aug. 31.

On Monday the Communist Party Convention met with 140 delegates representing approximately 58,000 members.

A committee of five from the “Left Wing” Convention met with a committee of the Communist Party to discuss unity. The CLP offered unity “on a basis of equality,” that is, to combine the two conventions as units, delegate for delegate. This the Communist Party rejected. The delegates in the Communist Labor Party Convention were a peculiar mixture, some of them openly repudiating the Left Wing principles and tactics, others notorious Centrists. The Communist Party committee proposed that all delegates at the Communist Labor Convention having instructions to participate in the Communist Party Convention (about 20) should come in as regular delegates; while delegates whose organizations had adopted the Left Wing Manifesto and Program, but who were not instructed to organize a Communist Party (about 20), would be admitted as fraternal delegates. The other delegates, representing an unknown constituency, or no membership at all, who were simply disgruntled at the Old Guard for its gangster tactics, could not be allowed to participate in the organization of a Communist Party.

The Communist Labor Party Convention refused this offer and proceeded to organize a permanent party. The delegates organizing the CLP represented not more than 10,000 members, many of whom are now joining the Communist Party.

This third party adventure was the result of a number of factors: personal politics, centrism, and the fact that Communist elements from the Western states had not been in close touch with the more rapid developments in the East.

Having consciously organized a third party, the Communist Labor Party is now making “unity” its major campaign. The former Left Wing organizations are almost entirely accepting the Communist Party, achieving unity through membership action. One word more: the CLP speaks much of “an American Communist movement” and fights our party on the issue of “Federation control.” This is malicious. There has been one disagreement with the Federation comrades: concerning this, it might be said that the Federation comrades may have been too precipitate and the American comrades too hesitant. But the Federation comrades have worked earnestly for an uncompromising Communist Party. In any event, if the Federations offer any problems, it is a problem of internal party struggle and action. The sincerity of the Federation comrades, all other considerations aside, is attested by their yielding administrative power to the non-Federation comrades.

The Communist Party Manifesto is a consistent formulation of Communist fundamentals; its Program a realistic application of these fundamentals to the immediate problems of the proletarian struggle; its Constitution based upon rigorous party centralization and discipline, without which a Communist Party builds upon sand.

6. THE GENERAL SITUATION

The Communist Party appears at a moment of profound proletarian unrest. There has been strike after strike, developing larger and more aggressive character. There is now a strike of more than 300,000 workers in the steel industry, a really terrific portent to American capitalism.

There is a revolutionary upsurge in the old unions; the longshoremen of Seattle have just refused to allow munitions for Kolchak & Co. to be transported. There is a strong sentiment in favor of the Russian Soviet Republic. In the unions the workers are becoming conscious of the reactionary character of their officials, and movements of protest and a sentiment for industrial unionism are developing.

But the American Federation of Labor, as a whole, is hopelessly reactionary. At its recent convention the AF of L approved the Versailles Peace Treaty and the League of Nations, and refused to declare its solidarity with Soviet Russia. It did not even protest the blockade of Russia and Hungary! This convention, moreover, did all in its power to break radical unions. The AF of L is united with the government, securing a privileged status in the governing system of State Capitalism. A Labor Party is being organized — much more conservative than the British Labour Party.

The Industrial Workers of the World is waging an aggressive campaign of organization. It has decided to affiliate with the Communist International; but its press and spokesmen show no understanding of Communist tactics. The IWW still clings to its old concepts of organizing all the workers industrially, gradually “growing into” the new society, as the only means of achieving the revolution; a conception as utopian as that of the moderate socialist, who proposes to “grow into” socialism by transforming the bourgeois state. The Communist Party endorses the IWW as a revolutionary mass movement, while criticizing its theoretical shortcomings.

Imperialism is now consciously dominant in the United States. In his recent tour for the League of Nations, President Wilson threw off the mask and spoke in plain imperialistic terms, emphasizing the absolute necessity of crushing Soviet Russia. Congress drifts, and is impotent. The government, federal and local, is adopting the most repressive measures against the proletariat. Armed force, martial law, and military invasion are used against strikes. State after state has adopted “Criminal Syndicalism” measures, making almost any advocacy of militant proletarian tactics a crime. On the least pretext agitators are arrested. Deportations occur almost daily; one of our International Delegates, A. Stoklitsky, is now under trial for deportation.

American imperialism is usurping world power, constituting the very heart of international reaction. Reaction in Europe and the campaign against Soviet Russia are supported morally and financially by “our” government. An enormous agitation is being waged for military intervention in Mexico. The American capitalist class is brutal, unscrupulous, powerful; it controls enormous reserves of financial, industrial, and military power; it is determined to use this power to conquer world supremacy and to crush the revolutionary proletariat.

The Communist Party realizes the immensity of the task; it realizes that the final struggle of the Communist proletariat will be waged in the United States, our conquest of power alone assuring the World Soviet Republic. Realizing all this, the Communist Party prepares for the struggle.

Long live the Communist International! Long live the world revolution!

Fraternally Yours,

Louis C. Fraina International Secretary

Attest: C. Ruthenberg Executive Secretary

Emulating the Bolsheviks who changed the name of their party in 1918 to the Communist Party, there were up to a dozen papers in the US named ‘The Communist’ in the splintered landscape of the US Left as it responded to World War One and the Russian Revolution. This ‘The Communist’ began in September 1919 combining Louis Fraina’s New York-based ‘Revolutionary Age’ with the Detroit-Chicago based ‘The Communist’ edited by future Proletarian Party leader Dennis Batt. The new ‘The Communist’ became the official organ of the first Communist Party of America with Louis Fraina placed as editor. The publication was forced underground in the post-War reaction and its editorial offices moved from Chicago to New York City. In May, 1920 CE Ruthenberg became editor before splitting briefly to edit his own ‘The Communist’. This ‘The Communist’ ended in the spring of 1921 at the time of the formation of a new unified CPA and a new ‘The Communist’, again with Ruthenberg as editor.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/thecommunist/thecommunist3/v1n03-oct-11-1919.pdf