Always compelling, revolutionary Marxist Charles Rappoport uses Tolstoy’s death to survey modern morality.

‘Tolstoy and Morality’ by Charles Rappoport from the New York Call. Vol. 3 No. 356. December 22, 1910.

The Marxian conception does not exclude morality or ethics. One would have to be devoid not only of common sense, but also of historical sense, to believe that any kind of society could exist without morality, in practice as well as in theory. Morality is one of the conditions of social life.

Marxism does not deny morals; it explains them. It throws the light on their contents, on their hidden workings, on their class character. It takes off their mask and proves that fine words frequently hide bad things. It exposes the hypocrisy of the dominant class by showing them that the universality of their morals is only a sham, because in a society based on the exploitation of the working class by the capitalist class, the general interest is of necessity subordinated to special interests.

Marxists recognize the existence of a proletarian morality. It represents an historical stage superior to the morality of the dominant classes. A moral regime based on universal solidarity must be infinitely superior to the morality of a society that has for Its vital principle universal competition, the struggle of all against all.

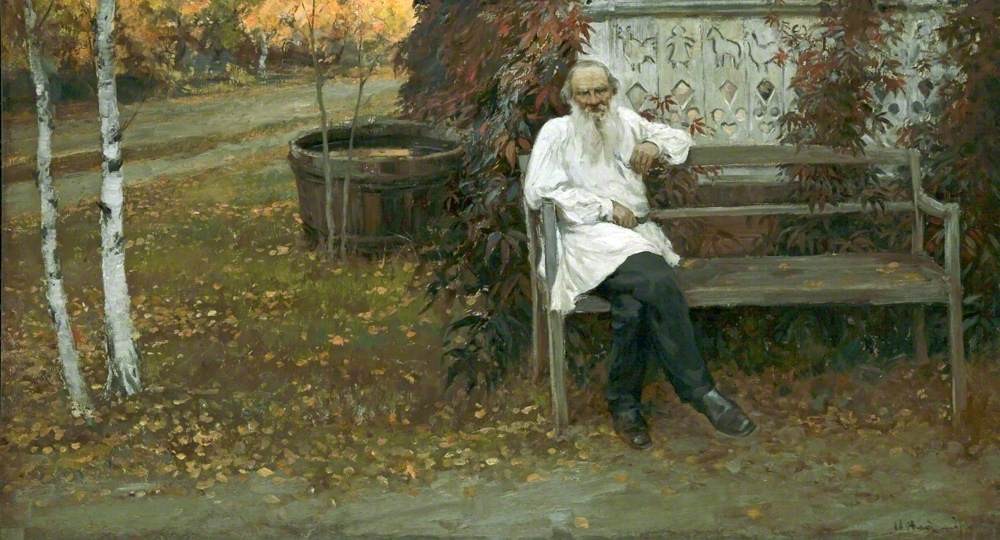

Tolstoy was at one and at the same time a great realist and a great utopian. He was investigator of the modern soul, penetrating its deepest recesses. He is the greatest naturalist writer, a Russian Balzac, more sober and more human than the other.

The artist, the psychologist, Tolstoy, was at the height of his time. surpassing considerably the crowd of imitators, to whom belles-lettres is a business like any other business.

But as philosopher and moralist Tolstoy belongs to another age, to the period of primitive Christianity, to the mystic sects, to the Anabaptists, the Quakers. Endowed with a high and profound moral sensibility, with an absolute sincerity, he felt for our regime of mud and blood an utter disgust. He tried to regenerate it through a kind of direct and immediate action of a moral nature; by regenerating himself, revolutionizing his own life, and arranging it in complete accord with his own ideas.

In his Confessions, Tolstoy relates how his conscience was mortally hurt at the spectacle of the horrible misery in the poor quarters of Moscow.

He saw and understood the miseries of the “lower classes” of society. He neither approached nor understood the modern proletariat, the fighting proletariat which rises above its own class, striving to emancipate society in its entirety.

Tolstoy knew only the peasants, brutalized by misery, and the slum proletariat, whose sight inspires no hope, no great idea. He was also ignorant of the revolutionary role of capital in developing the productive powers of society. And he addresses himself to the privileged classes first of all. from whom he himself comes.

Finding nothing there, he was too great a realist, too great a judge of life to believe in the “co-operation of classes”, he returns to himself. He discovers the gospel. He proclaims “salvation lies in yourselves.” But this great moral prophet, this great apostle of sound morality, could not so deceive himself as to overlook the fact that the official religion is only an instrument of class domination. He states that he casts off the church, its rites and worship. All he retains from the gospel is its pure morality and God, whom he identifies with love for humanity. And this man, the only Christian in our society, naturally, was excommunicated by the so-called Christian Church. The same would have happened to Christ himself.

Like all utopians. Tolstoy is at the same time empirical and utopian. He wants to put an end to all our miseries at once, with one stroke. He addresses himself to his contemporaries, telling them: “You complain of the exploitation of man by man, of the continuous robbery, of the numberless iniquities. There is only one thing for you to do–stop exploiting, stop robbing, stop killing. Be just.” And he preaches by example. He deserts the high society which is willing to cover him with honors. He lives like a peasant, like a worker, and tells others: “Do as I do and society will be saved.”

As a result, Tolstoy ought to have known that he will not be followed. Because the individuals are the ones who follow society, never was there a society shaped according to the imagination of one individual.

This Christian moralist tried first of all “to save his soul.” Tolstoy was an individualist. He was an anarchist, without the violence. As such he was fundamentally an egoist, with a superior, sublime kind of egoism, who thought only to save his soul, who wanted society regenerated in order to have his soul at peace.

Thousands of Russian Socialists who, at the same time as Tolstoy, tore themselves away from their class “to go among the people,” to suffer, fight and die for and with them, not only had a social conception superior to his and more in conformity with modern society; they had something greater yet–a superior morality, greater, nobler and more humane. They performed acts of violence repugnant to their own self, they neglected to think of their own “soul.” They forgot themselves, thinking of the social revolution. The bourgeois world will not cover them with wreaths. It will either ignore them or blaspheme them.

There is something more yet. The moral ideal of Tolstoy is fundamentally reactionary. As an ascetic, Tolstoy is the enemy of life. Acquiring a great disgust for the present forms of life, in his hatred he confuses these transitory forms, these “historical categories,” with life itself. He turns away from It, with horror.

In Kreutzer Sonata he wrote:

“When I see a proud, beautiful and adorned woman, I feel like calling a guardian of the peace and telling him to do away with this public dancer.'”

He considered family life a shameful concession to our impure desires. To follow Tolstoy, life would be “morally” pure–but also pure of all earthly enjoyment, of a discouraging monotony. It would not be worth while living. We would live for others. There are three systems of morality. First of all we have the Christian morality, the morality of resignation. It is the morality of the decaying regimes, of the dying societies, the morality of despair, disgust, pessimism. Such is the morality of Tolstoy, the morality of unconscious, submissive muliks, products of centuries of blind submission. It leads to the deeply immoral and demoralizing doctrine, that of non-resistance to the evils of violence, and this doctrine for the great majority becomes non-resistance pure and simple. It is also the morality of the slum proletariat, unfit to fight and to conquer, the morality of the slaves.

We have on the other hand the morality of the dominant classes, “the morality of the masters,” of Nietzsche. It is the sanction of all that exists. It proclaims: “Be harsh. Nothing is true, everything is permissible.” It has the merit of sincerity. Only credulous thinkers like George Sorel try to adapt it to the proletarian and “revolutionary” aims.

Finally, we have the proletarian morality, a result of the fruitful struggle for a new society, the morality of a producing class which raises its vital principle productive labor–to the height of a universal principle. It is neither inspired, nor dogmatic. It is the social future, transformed into social duty. It is imposed by the natural and social conditions of existence. In order to live, we must produce. And to live well, we have to produce, not for the market, to create profits for the capitalist, but for humanity and society. It is no more the isolated genius inspired by a password from above, but an entire class which produces everything, is inspired by capitalist production itself, and says society: “Do as I do. Work, produce! The regime of iniquities and infamies will exist no more.”

The working class relies only on itself and on its struggle to impose this morality of the future, this morality of life, upon a new and renovated world.

It will love Tolstoy for his sincere hatred of capitalist iniquity, but it will not follow him.

The New York Call was the first English-language Socialist daily paper in New York City and the second in the US after the Chicago Daily Socialist. The paper was the center of the Socialist Party and under the influence of Morris Hillquit, Charles Ervin, Julius Gerber, and William Butscher. The paper was opposed to World War One, and, unsurprising given the era’s fluidity, ambivalent on the Russian Revolution even after the expulsion of the SP’s Left Wing. The paper is an invaluable resource for information on the city’s workers movement and history and one of the most important papers in the history of US socialism. The paper ran from 1908 until 1923.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-new-york-call/1910/101222-newyorkcall-v03n356.pdf