Facing 18 to 20 years of hard labor on the chain gang for ‘insurrection’ (having Communist literature available in a public library) by Georgia, Angelo Herndon was out on bail awaiting appeals when he visited the most famous political prisoner in the United States, Tom Mooney, and did this interview.

‘”I Have No Illusions” An Interview with Tom Mooney’ by Angelo Herndon from Labor Defender. Vol. 11 No. 1. January, 1935.

“WHAT do you think the United States Supreme Court will do about your case, Tom? Do you think they will let you go?”

As one political prisoner whose case is coming up before the court of last illusions to another, I asked that question of Tom Mooney. It was one of a whole series I asked in the hour I had with him, visiting him in San Quentin prison. His answer–much the same answer, allowing for different circumstances, that I would have given had anyone asked me “What do you think the United States Supreme Court will do about your case, Angelo?”-was:

“I have no illusions about what they will do. For eighteen years they have refused to have anything to do with my case. In fact they have kicked and tossed me around so much, I can’t expect anything from them unless the protests of the working-class will force them to free me.’

I asked another question along the same line:

“I suppose you know that Professor Moley has asked Governor Merriam to pardon you so the workers will stop making such a noise about your frame-up?”

“Yes, I know about that,” Tom said. “But you see there is Scottsboro, your case, and mine, all coming up before the Supreme Court. Moley thinks that if Merriam pardons me, the case will not go up there, and so they will be saved further exposure.”

When I asked to see Mooney, I made the trip to San Quentin from San Francisco, where I had been speaking on the Scottsboro case, one of the guards disappeared behind trick steel walls and we could hear him yelling:

“Mooney! Three-one-nine-two-one! Mooney! Three-one-nine-two-one!”

Within a few minutes, Mooney came out, dressed in his white prison garb. He was smiling. He leaned over the wooden partition between us to shake hands.

One of the comrades from the San Francisco International Labor Defense introduced us.

“I have heard all about the frame-up of the Scottsboro boys, and yourself,” Tom said. “I am glad to see you out, and for you to pay me a visit is indeed a treat.

“I know Georgia,” he went on. **I remember away back before the ruling class of California framed me, how they used to treat Negroes. There was the ‘Williams Farm’ down there, where they used to work the Negroes until they were almost dead. Then Williams, the plantation-owner, would make them dig their own graves, and kill them with an axe. I think he was put in prison, later. As savage as they are, it is surprising they let you go around the country speaking against your frame-up.”

“Tell me how they handle the prisoners here,” I said. “What privileges do you have, as one who has spent 18 years here?”

“I have been here a long time now,” Tom said, “and they are forced to treat me with some respect. But when my dear old mother died, and her dead body was brought to the gates of the prison years ago so that I might see the last remains of a dear old soul who had fought and suffered for her son and her class, they would not even let me go as far as the first door leading to the outside.”

There were tears in Tom’s eyes.

“She was a real fighter,” he said, “who spent her last days on the battlefield, always agitating and organizing her class brothers and sisters for the final upheaval that will not only set her innocent son free, but break the chains that are bound around the necks of all workers.”

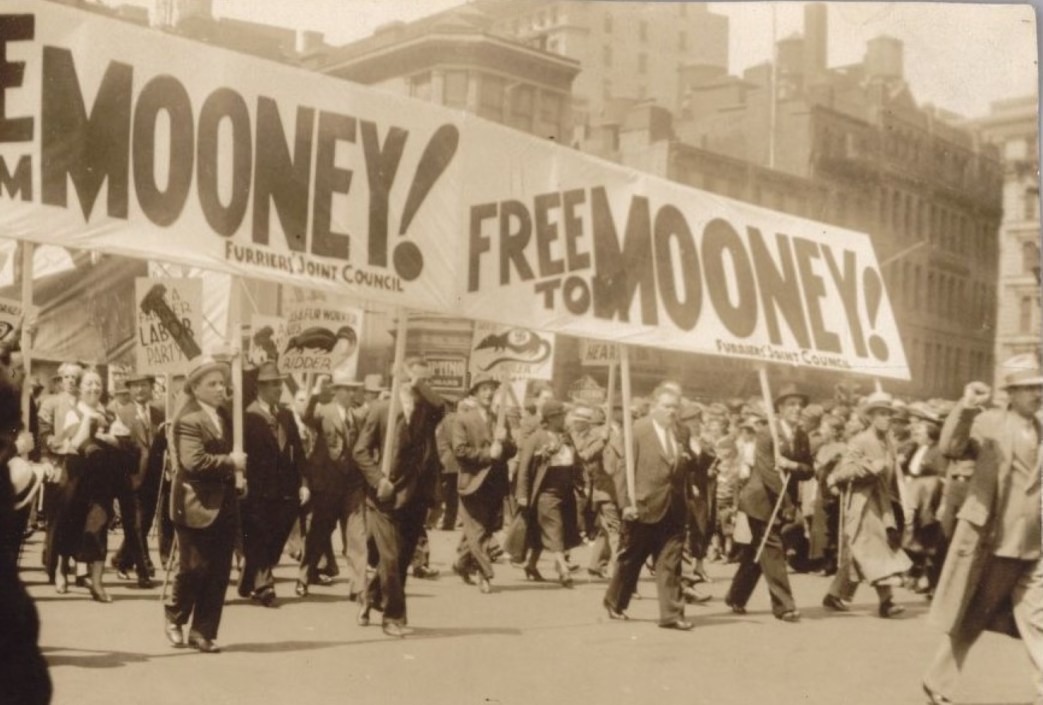

I told Tom about what I had seen and read of the workers fighting for his freedom all over the world, about the meetings of the I.L.D. where I spoke on the Scottsboro case, and how there was never a meeting where the question of his freedom was not raised, and how warmly the workers receive it.

“I am grateful to all those who have been fighting for me all these long 18 years,” he said. “I only want to say that if the fight is intensified the capitalists will be forced to accede to the demands of the workers.”

It was at this point that the two questions I spoke of at the beginning of this account of my interview with Tom Mooney were asked and answered. We talked about the life of workers in the Soviet Union.

“I don’t think the time is very long now,” Tom said, “before the workers of this country will do away with their exploiters and set up their own workers’ and farmers’ government, as the workers have done in the Soviet Union.”

The guard jerked his thumb at Tom and said: “All right, Tom, your time is up.”

We continued to talk for another minute or two.

“What would you do if they let you go, Tom?” I asked. “Take some rest, or maybe pay the workers of the Soviet Union a visit?”

“I would like to go to the Soviet Union to thank the workers there for saving my life,” he said. “But we have a big job on our hands in this country. If they do let me go, I will plunge right into work.”

As I was leaving, he said:

“Goodbye. I am glad you stopped by to see me. Give the workers of America my best revolutionary greetings and tell them that I have all confidence they will set me free in the near future.”

The big steel gate swung behind us, and Tom was busy again at his usual routine of work.

I was outside, on $15,000 bail that the workers and sympathizers raised through the I.L.D. to get me out of Fulton Tower, and with another rich experience behind me to help me continue the fight for the freedom of Mooney, the Scottsboro boys, McNamara, and all the other class-war prisoners.

Tom made a deep impression on me. It was especially inspiring to know from his own lips that in spite of the 18 years he has been forced to spend behind the walls of San Quentin, he is still determined to help carry on the struggle for the emancipation of the working-class.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1935/v11n01-jan-1935-orig-LD.pdf

Thank you for this amazing piece of history! Tom Mooney was my grandfather’s cousin, Mama Mooney my great great aunt, and I am down the rabbit hole. I was delighted to find not only this interview that I’d never read before, but the publication that is linked here – Labor Defender – is a very interesting piece of history as well.

LikeLike