A fantastic look at the history, economy, and conditions in the western metal mining industry, the seat of so much class conflict in U.S. history, in a two-parter by Communist miner Jack Lee.

‘The Rocky Mountain Miners’ by Jack Lee from Workers Monthly. Vol. 4 Nos. 2 & 3. December & January, 1925.

IMAGINE a desert region men long, flat, sandy valleys between low ranges of hills. The plain between the hills is treeless, and is cut by dry water courses—down by the Mexican border they call them arroyas, and farther north they call them washouts, but they are all the same—sharp, narrow, steepbanked things—very awkward to run into with a Ford. Transportation is rotten. There are no real roads, except near the cities, but there are sign boards standing lonesome-like in the plains, and wheel tracks going this way and that, where Fords or trucks commonly run to some mining camp or other.

You can watch distant dust clouds, where supplies are going to camp, as you sit on the hillside in the cool of the summer evening and look across the sage, which is purple when the light begins to fade, and see other hills—lavender hills, these are—with a greenish colored sky behind them.

I think it must be the amazing color schemes in this plateau region (which is most erroneously marked on maps, “The Rocky Mountains”) that makes people go back to it the way they do. I can’t see any other reason, unless, of course, they own a mine. For this stretch of hills and high barren plains, running from Arizona to Canada, is one of the world’s treasure chests. The greater portion of the copper produced in the United States comes from here, and practically all of the silver, lead, platinum, zinc, and tin. Millions of dollars worth of gold comes out of here every year—much more, contrary to the public impression, than Alaska yields. Sometimes all of these metals are mixed together in the same mine, and gold, silver, lead, zinc are usually found together, and principally in the southern half of the region I have described. Copper is found mostly in the north, where there are a few real mountains.

The “Promoting” Industry.

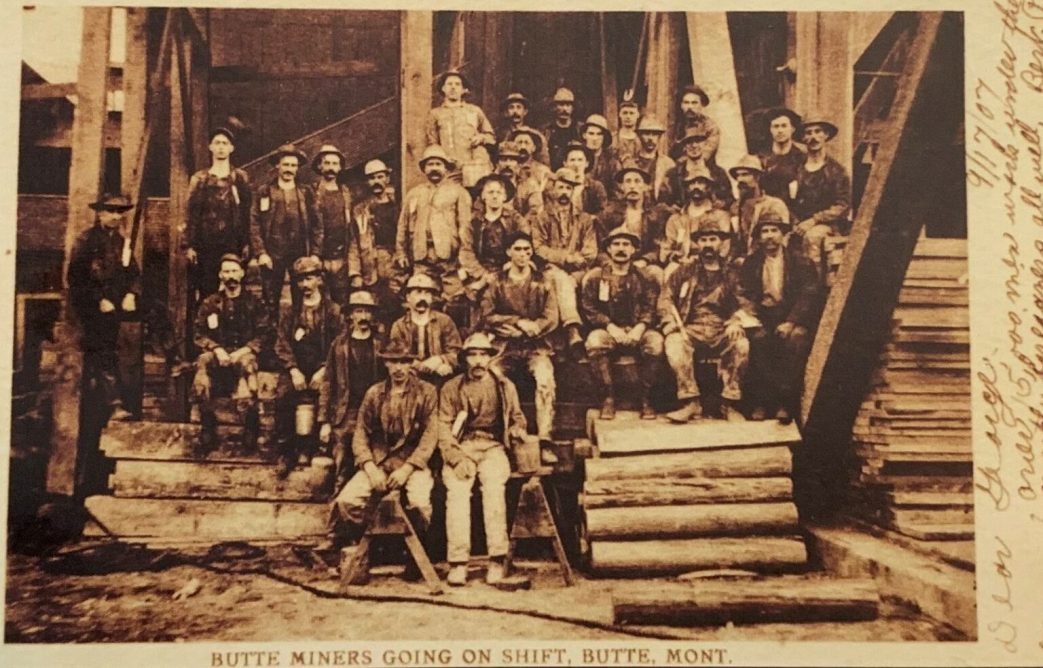

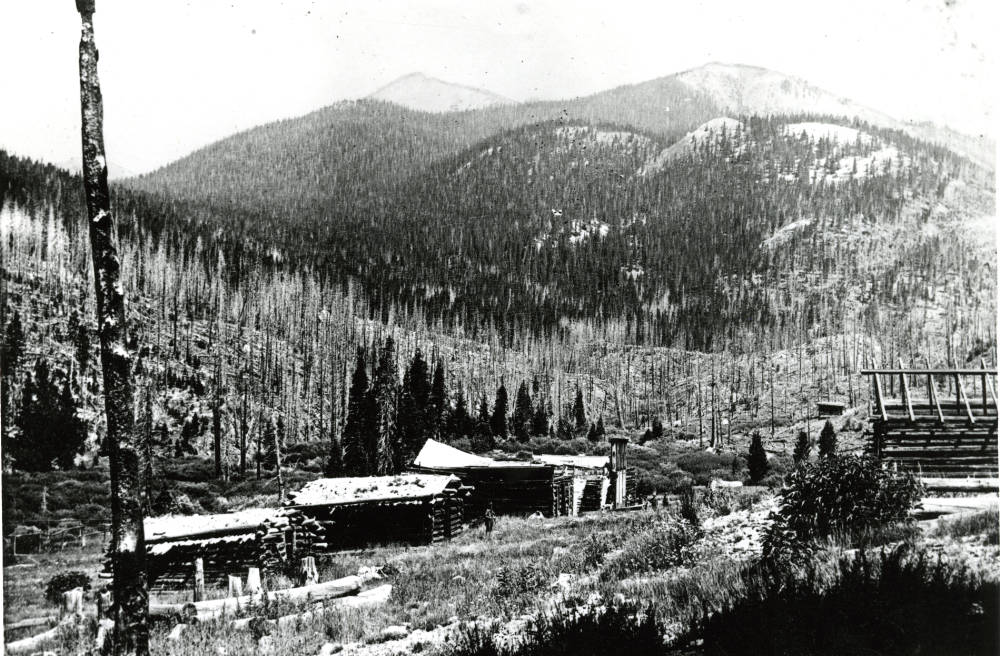

Some of the mining, particularly copper mining, is done in little cites, like Butte and Helena, towns that are surrounded and supported by mines, but which are considerable settlements, for all that. But much of the mining, and all of the prospect work, is still carried on in distant canyons, twenty, fifty, one hundred miles from the railroad, and it is done by methods that would not justify the existence of these enterprises in a soviet system of economy.

A surprisingly large number of mining enterprises do not produce anything at all. The Bureau of Census Mines and Quarries Handbook states that in 1919 there were five hundred enterprises, operating 512 mines, or one-fourth the total number of mines in operation, which did not produce anything at all. These mines are supposed to be “developing,” that is, being dug down to the ore bodies. Most of them never find any ore bodies that it will pay to work. They run on for a year or two, and disappear, but others start up instead of them.

All Nevada, Arizona, and Colorado, and much of Utah is lined with low grade silver ore. It is the easiest thing in the world to find a mine, if you don’t mind staking out ground that it will not pay to mine in.

After the enterprising prospector locates the “ground,” his next and hardest task is to find the “live one.” The live one is somebody from the East who doesn’t know anything about mines, and can be persuaded to finance a mining company. Usually some professional promoter starts a company, and those who finance it are $12 per day (two months a year) New York bricklayers, or tired middle western farmers who think they can buy mining stock with their second mortgage, and thus get rid of their first one; or they are retired grocers in some small Ohio or Indiana town looking for an easy way to serve the Lord. All money is the same, and it all goes to give the promoter a little rake-off, and to the original prospector or the wise bird to whom he sold out for a song, a somewhat lesser reward, and it provides a few months’ work for the common miners and muckers. The miners and muckers get cheated out of their last two months’ pay when the company goes broke. The farmers and petty bourgeoisie and the workers who have taken a fifty-dollar flier in mining stock, get nothing. But some silver and lead is frequently produced, at a cost of two dollars for every dollar taken out, and the stock of such metals in existence is thereby added to. Much mining is swindling, even by capitalistic standards, and practically all small mining is swindling. Every miner knows this.

Freezing Out The Small Producers.

I can remember the first sight I ever had of a silver mine. It was at Tybo, seventy miles from Tonopah, Nevada. A tall, raw-boned shift boss stood leaning over the railing around the mouth of the shaft, waiting for the cage to come up. When it was hauled level, the first muddy, dripping miner stepped on the ground and announced, “A new vein in Number Three Winze.”

Says the boss, “How wide is it?”

“About as wide as my hand.”

“Wide enough, wide enough—and I know it runs clear back to New York.” (New York was where the “live ones” lived, in this particular case.)

That is the general attitude; and this universal atmosphere of fraud, “high-grading,” petty graft and big graft, “salting” of mines, murder of unwelcome inspectors (“rolling them over with a short starter,” the miners call it, meaning, getting the intruder killed by a purposely premature blast), may perhaps account for the rebellious and generally anticapitalistic spirit of the metal miners.

When you see the time-keeper padding the pay-roll to get some graft for himself, and the mine superintendent stealing an occasional truck load of silver ore for his bucks, and the president of the company putting out the most ridiculous and exaggerated claims to get some sucker to buy stock, you know capitalism is rotten, and no one can convince you otherwise.

Time was when the individual miner might steal a few chunks of rich gold ore himself, every shift. That period is gone. You couldn’t carry away in your pockets enough twenty-dollar-per-ton ore to help you much.

But for the man with a little money, opportunities for theft are still quite common. I have seen the most impossible things stolen. I knew one mine superintendent who regularly stole all his spare parts for mine and concentrating mill machinery, all his steel for new tools, all his small dynamos and motors and wire, from other and temporarily abandoned mines around the country. Some of the mines from which he stole were a couple of hundred miles away. Usually some watchman had to be either bribed or bumped off, as the virtue or lack of virtue of the man demanded. But the “super” always got the stuff he went after—he just sent a truck and got it—that was all.

I know of one case, near Salt Lake, where a group of ambitious workers put the lessons they had learned, to good use, and stole a smelter—pretty nearly the whole thing. They began in a small way, taking the brass parts and copper wire and selling them, from which they got money enough to buy a horse truck, after which they stole motors and pieces of pipe, and got money enough to buy a good four wheel drive motor truck, and in the end they were trying to get away with some of the big furnaces, when the owners interrupted. I believe these men have formed a company and own mines themselves now, proving that the Chicago Daily News is right, when it alleges that there is still room for hard working persons to climb to comfort and even affluence through the “Romance of Small Business.”

The Real Exploiters.

Now, just becuase a good deal of the silver lead is produced by little mining companies, more or less wild-cat in nature, it should not be supposed that big business plays no part in the metal mining industry. Even silver lead has to be smelted, and much of the ore has to be concentrated first. The mills and the smelters are pretty much in the control of George Wingfield, of Salt Lake, and of the Guggenheim family, of New York. They get the really big profits, and in purely legitimate ways take much more than the little swindlers get in illegitimate ways. They buy the ore or the concentrates from the mining companies at the smelter’s own price, and they come pretty close to selling the stuff, after it passes through their hands, at what price they please. Also, they do things like this: When galena ore is sold to them (most of the Nevada and Arizona ore is galena) they know it contains silver, lead, zinc, and gold. They buy it for the silver and lead it shows on assay, and refuse to pay for the gold, if that is in small quantity. They actually charge the mining company for all the expense of removing the zinc from the rest of the metals. Then they sell the zinc—clear velvet. I have seen mining superintendents turn purple in the face and choke with rage when describing the extortion and greediness of the smelting trust, but I have never observed that it hurt the Guggenheimers any.

As a result of their grasp on the smelting and refining end of the silver lead mining industry, Wingfield and the Guggies buy up for very little the best of the mines, the real mines, which it pays to operate. If you have a good mine, and one of these mining capitalists wants it, you might as well take his first offer, for he will never make another as good, neither will you sell any ore to amount to anything after the first offer is made. Moreover, if you are stubborn, your cars of ore will mysteriously go astray, and the railroad company will deny that they ever existed, and sabotage will break out in your camp; your working places will be flooded, and your employes will be poisoned, and your hoisting sheds will be burned. All these big pirates of the mining industry stand together, and their spies are everywhere.

Concentration of Capital in Metal Industry.

Such advantages, and the fact that the ores most easily worked have been used up, necessitating for the mining of lower grade ores more complicated technique and more expensive machinery, have resulted in the rapid concentration of the gold-silver-lead-zinc mine companies and the still more rapid centralization of ownership in the copper fields.

Let us take up the gold-silver, etc., mines first, and resort to government figures. According to the authority quoted above, in 1902 there were 2,017 gold and silver lode enterprises; in 1909 there were 1,616, with 2,011 proprietors or firm members, and in 1919 there were but 740 enterprises, with but 712 proprietors or firm members. Later figures are unobtainable, but the process indicated above is continuing. Notice that the number of proprietors was greater than the number of enterprises in 1909, but that in spite of the great concentration of enterprises in 1919, the proprietorship was still more concentrated, so that there were fewer proprietors than mining companies. It is true that the decrease in the number of mines may be accounted for by the fact that the value of the ore mined decreased from about seventy-seven million dollars in 1902 to about fifty million dollars in 1919. That is, the industry itself is smaller now than it was.

But when we take up the case of the lead and zinc mines (remember that this governmental division into gold-silver and lead-zinc groups is artificial and arbitrary, for all the metals are usually to be found in the same mines) we find that the value of the product has enormously increased: in 1902 it was $14,600,177, and in 1909 it was $31,360,094, and in 1919 it was $75,579,347. Nevertheless, in spite of this enlargement of the industry, there has been a concentration of control. In 1909 there were 977 enterprises with 1,947 proprietors or firm members, and in 1919 there were but 432 enterprises and 412 proprietors. Notice again that the proprietorship has concentrated faster even than the business units.

Many a man is still alive who can remember the time when George Wingfield was a “tin-horn gambler.” Wingfield gambled in the way that never loses, and put the profits into banks and mining companies and smelters. Now he owns the Goldfield Consolidated Mines company, the Nevada Hills Mining company, the Buckhorn Mines company, and he is president of four big banks. He controls many more companies.

The Guggenheim brothers own both silver-lead and copper projects, among which are: the American Smelting & Refining company, Smelters Securities company, Braden Copper company, Guggenheim & Klein, Inc., Chile Copper company, Chile Exploration company, Braden Copper Mines, Ne. vada Consolidated Copper company, and a number of steamship lines and railroads. Morris Guggenheim is the treasurer of Gimbel Brothers department stores, and Simon Guggenheim was United States senator for six years, from Colorado.

These two are outstanding examples of the newer capitalism in the metalliferous lode mines. The Rockefeller family, too, is working in deeper all the time.

The Copper Trust.

When one considers the copper mining field, he will, at first sight, believe that no concentration is under way. In 1909 there were 188 enterprises with 79 proprietors or firm members, and in 1919 there were 195 enterprises, with 103 proprietors. But there is centralization of power, just the same.

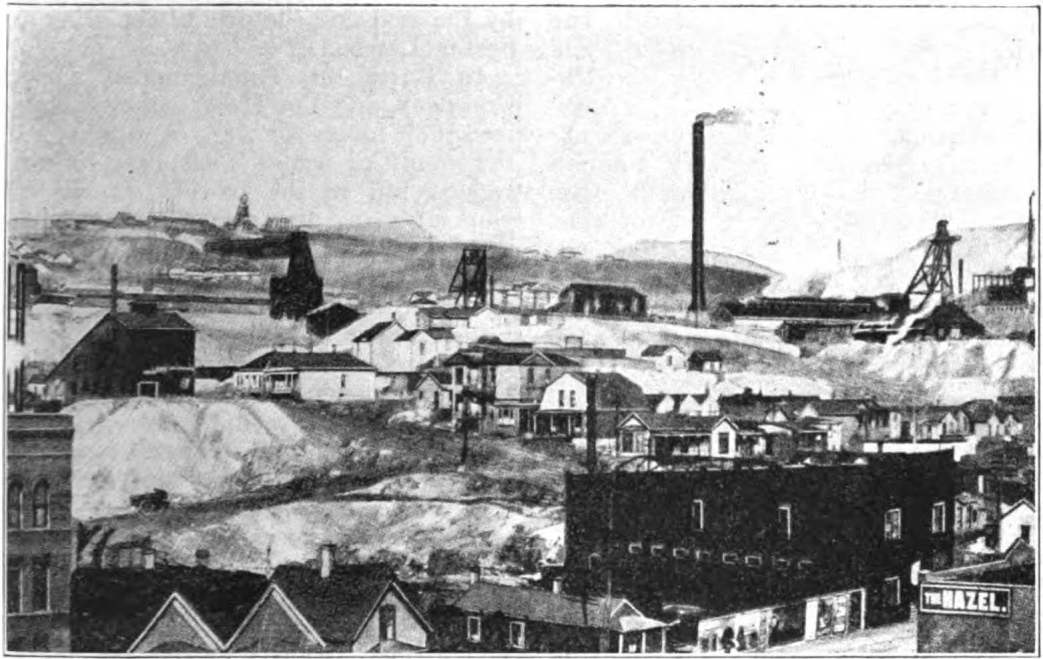

About a hundred of these enterprises are in the Rocky Mountains. One of them is the Anaconda Copper Mining company, with headquarters in Butte, Montana. Most of the other ninety and nine are also the Anaconda Copper Mining company, hiding under different names.

YOU can’t find out now what the Anaconda Copper Mining company makes in yearly profits, but in 1916, before the Industrial Relations Commission, C.F. Kelley, Anaconda vice-president, boasted that the company cleared $11,000,000 per year. The company makes enough to expand. During the last ten years it has bought and merged with itself the International Smelting & Refining company, which cost it $10,392,709, and the United Metals Selling company, which cost it $6,624,583, and the Pilot Butte company, at a cost of $1,125,000, and the American Brass company, which cost $22,500,000 (with some Anaconda shares thrown in), and the Alice Gold and Silver company, Inc., and the Walker Mining company, and the Arizona Oil company, and the Anaconda Lead Products company, and the Copper Export Association, Inc., and oh, lots of others besides these big ones—quite a number of South American companies lately, too.

Moreover, the 188 enterprises mining copper in 1909 produced but $134,618,987 worth of the metal, whereas the 195 enterprises mining in 1919 produced $181,258,087 worth. Some correction should be made for rise in price of copper, but still, the field has expanded out of proportion to the increase in even these nominally independent enterprises. The Anaconda, of course, has a grip on the western smelters. Over in Michigan, the Calumet & Hecla functions as the Anaconda does in Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Chile, Peru, and other places. Probably they are the same company, too. At any rate, they do not compete seriously.

What of the Workers?

So much for the mining companies, and the mineral product itself. Now, what about the fellows who really do the work of getting the metal out of the ground?

When you remember some of the epic struggles of these western miners and think of Ludlow, Bisbee, Butte, and the fighting that took place there, you wonder what sort of men live in these crowded copper camps, and lonely silver-lead camps, and seem at times so extremely militant and well-organized, and at other times so confused and helpless.

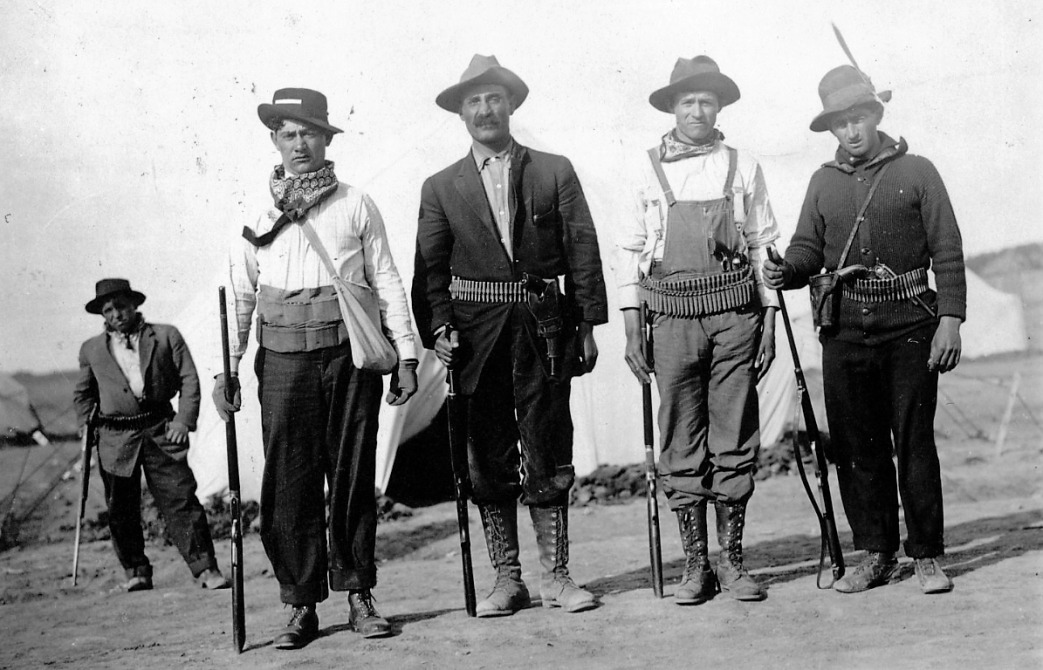

In the first place, you should recollect that there are five main national groups: Irish, Poles, Mexicans, Finns and “Cousin Jacks” (Cornishmen). The employers keep thousands of stool-pigeons, and agents provocateurs, and subsidize national churches, and promote national newspapers, just in order to keep nationalistic differences sharp and well-defined. At periods of open and flagrant class war, such as the times of the massacres and the decade of militancy in the Western Federation of Miners, these nationalist groups have been able to sink their differences and unite, but only temporarily. No one needs the Communist teachings of internationalism more than the metal miners need it, and no group of men in the world would repay the effort of the teachers better.

Then, it must be remembered that the metal miner is a sick man. Prospecting is a fine, healthy trade, though poorly paid. At the present time, open pit, or steam shovel mining, is not so bad. The old “single jack” and “double jack” (hand mining) method was healthy as long as mines did not go too deep, as they usually didn’t, being without machinery.

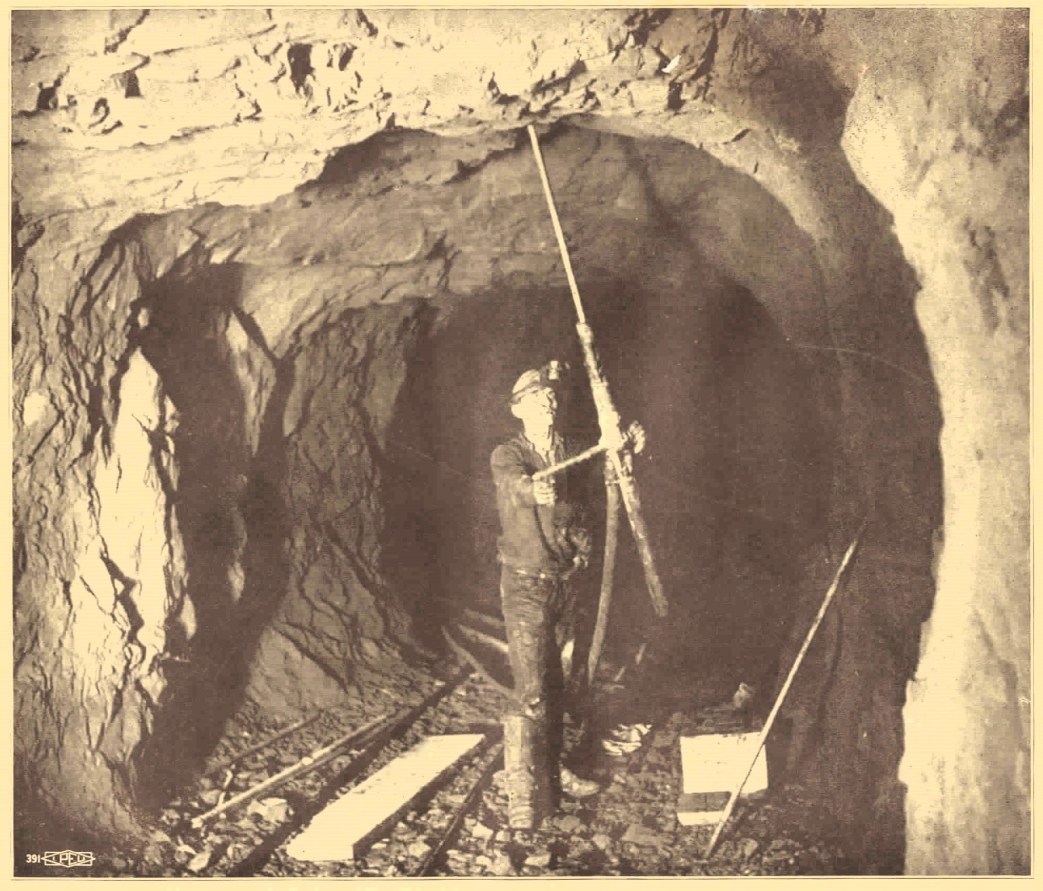

But the compressed air power drills—the “jack hammers,” “wall machines,” “piston machines,” “swivel tails’— drove hand mining out of existence. There are still a few old-timers who refuse to hold a jack hammer in their arms, and stick to hand mining. They are used for prospect holes. During the last ten years a further reduction in man-power has resulted from the substitution of the one-man drill for the two-man drill.

Eliminating the Metal Miners.

Though the output of ore has increased, there are actually fewer miners engaged each year than there were the year before. In 1909 each employe in the copper mines put in motion $5,846 of capital, and produced for the master during the year $2,586 worth of copper; in 1919 each employe put in motion $19,526 of capital, and produced for the copper companies during the year, $4,146 worth of copper. In the lead-zinc mines in 1909, each employe operated about $3,700 worth of capital and produced during the year about $1,890; while in 1919, the capital per man was nearly $9,000 and the product per man per year was about $3,500. In spite of the much greater capitalization and much greater product in 1919, there were employed in all the non-ferrous metal mines in 1919 some fifteen thousand fewer workers than in 1909. In comparison with the capital, the reduction in man-power is greatest in the copper industry, in which, by the way, there is an almost perfect example of the tendency, pointed out by Marx, whereby the increase of constant capital proportionately at the expense of the variable capital brings a lower rate of profit, though a greater absolute profit.

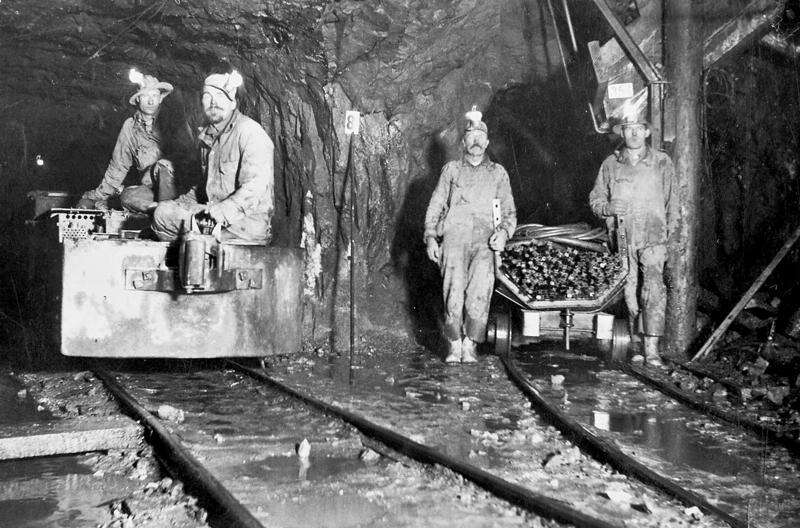

More machinery and a reduction of the number of men employed in the industry, means fast work to hold your job, harder work, and willingness to take risks. The risks have increased. Deeper mines mean more accidents in the shafts, and they mean greater heat.

Consider how these men work. There are three shifts in most mines; the morning shift starts at 7:30 a.m., and comes off at 3:30 p.m.; the night shift starts then and comes off at 11:30 p.m.; the graveyard shift starts at 11:30 and comes off when the morning shift is ready to go on. Every two weeks the men change shift, and there has to be a relearning of all the appetites and physiological functions, sleep, etc.

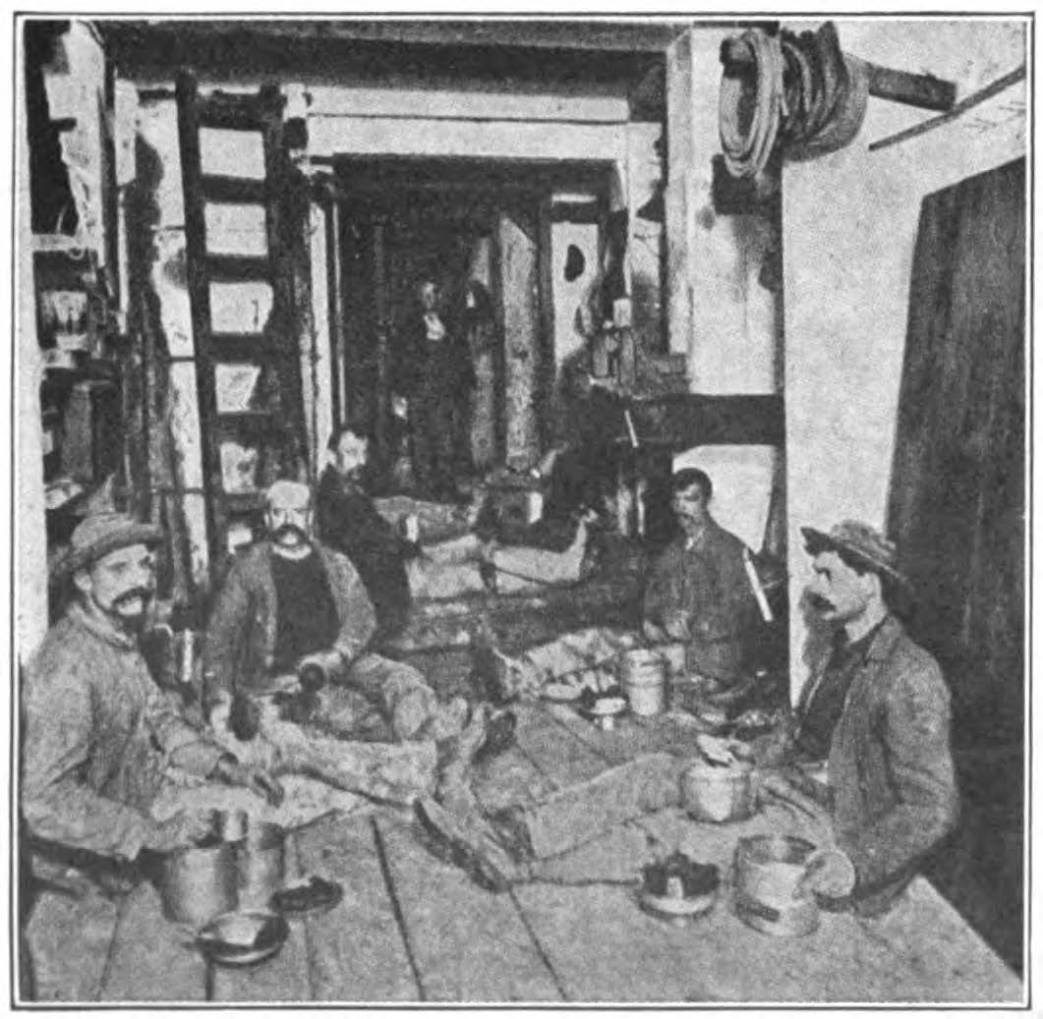

In the bigger towns, like Butte, the miners live in as crowded and insanitary conditions as East Side New Yorkers do. In little company towns, hidden out in the canyons, they live in a “crummy” bunkhouse, and in either case, they do not sleep with air enough around them or heat enough in winter. Then they rush out of their beds, in the middle of the night, maybe, through snow and ice, forty degrees below zero, sometimes, into the cages that take them below. The surface men, ore sorters, engineers on hoist and compressor and pump engines, hoist men themselves, dumpers, carpenters and surface shovelers very seldom go below and do not suffer from hot mines and dust.

In the Bowels of the Earth.

But the miners and muckers are carried down, in some mines, nearly a mile—frequently more than 2,500 feet. They probably go down a straight shaft, which is like the elevator well in a large building, with elevators, called “cages,” running up and down. At “levels” every hundred feet—vertically—some of the men get off, and go to the “face,” that is, the working place. Some work in “drifts,” merely tunnels, running out horizontally, starting from the shafts. The face of a drift is vertical, or nearly so, and the machine miner drills holes seven or eight feet long, more or less horizontally back into it with a compressed air drill. A good deal of dust is thrown out, unless the drill is one of the sort that washes out the chips with water. If the miner is sinking a “winze,” which is a new shaft, started in the floor of some undergrown working, and not at the surface of the ground. he will probably be standing to his ankles or higher in water; while if he is “raising,” that is, starting a shaft at the bottom, and going up through the roof of some underground workings, he will have a horizontal face, above him, and will probably not be able to use a water drill, as the water would all fall back on him. In that case, he “eats dust,” which is thrown out of the hole by the compressed air exhaust. There is invariably plenty of other dust in the mine, for the companies prefer the dry drill method—it is quicker and less expensive. Every movement of the drill in a dry mine, every explosion, stirs up rock dust, and makes more dust. Even the cars that run down the drifts carrying ore and waste rock on very narrow gauge tracks, stir up dust in their passage. The mucker, shoveling rock into the cars, raises clouds of dust—all this in a confined space, and in mines of 2,000 feet depth or more, in a temperature ranging from 90 degrees to 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

Destroying the Miners’ Lungs.

The dust in copper and zinc mines is largely flint, or silica. Its finer particles are flakes; under the microscope they look surprisingly like little knife blades. All underground workers have silicosis or “miners’ consumption” to some degree. This is not true tuberculosis, though the symptoms are similar—it is merely an accumulation in the lung tissue of quantities of these flint knives which have sliced through the walls of the air passages. Silicosis paves the way for, and invariably induces true tuberculosis, sooner or later, unless the man quits his job.

Government figures prove the death rate from tuberculosis is thirteen times greater in Butte than in Michigan, which is also a copper mining state. (Bureau of Mines, Technical Paper 260).

Men, particularly in raising and sinking, wonk in cramped positions, and in very bad light. Miners’ nyastagmus, a disease of the eyes, and also a trembling of the face and hands are therefore very prevalent. Cramped positions and falls are common to men working in “stopes,” also. (Stopes are large chambers irregular in shape, from which ore is being taken.)

The excessively hot and humid atmosphere in deep mines is itself depleting and emaciating, raising blood pressure and raising the mouth temperature in some cases to 102 degrees, which is decidedly fever heat. The conditions make it impossible to think quickly and this increases the chance of accidents. (Public Health Reports, Jan. 28, 1921) In 1916, several thousand workers in the Mother Lode of California, were discovered to have hookworm, and it is certain now that other mines are likewise afflicted.

Leaving the overheated mine at the end of the shift, and walking in sweat-soaked garments to a “wash-house” Is somewhat conducive to pneumonia, as many a miner or mucker has discovered.

Practically every worker in silver-lead mines is “leaded,” or has what is called in another trade, “painters’ colic.” Not infrequently the miners die of it.

Then it must be observed that all this country is very high, 10,000 feet to 14,000 feet above sea level, and altitude alone plays queer tricks on men’s minds. It makes them morose, and quarrelsome, usually, though sometimes hysterically jolly. Many a time I have come off shift at 7:30 a.m. with a raging headache and spots dancing before my eyes, and sat down to an utterly tasteless breakfast. It was not that the food was so bad but that we all felt too sick and tired to eat. Then for hours we would sit in one long row along the bunkhouse wall, not talking, not thinking, just sitting there with an utter loathing each of us for his neighbor. It’s a great life. You really have to live it to realize it—and then you won’t. You only see it properly after you have left it for several years.

Take a “leaded” or tuberculous miner, up eleven thousand feet, shut up in a bunkhouse with two hundred or two hundred and fifty other men, and you have a most uncertain proposition. He surely is ready to fight, and he usually fights his fellow workers. The problem is, how to use in a fight with the mine owner some of this rage that is now going to waste.

The national divisions, and the unsanitary working conditions, plus the inevitable stool-pigeons, explain, I think, why the best fighting proletarians in the world, and in some ways, the best educated to the iniquities of capitalism, fail to de better at present; why they waste their time in futile personalities and group conflicts, and sink into worse and worse economic and social conditions.

A powerful union could easily wring bigger wages from the companies, and force installation of dust-laying devices. Good wages (machine miners get $4.75 to $5 at present, but living is expensive) and the two-man drill (one-man at present), and abolition of contract work, would wipe out the evils of unemployment and the slum conditions.

We need a fight, and miners surely can fight. At present though, they need organization. The two unions which exist—dually—among miners and smelter workers do not afford even the protection of their name to as much as five per cent of the miners. There are about 80,000 mine workers, and probably 20,000 smelter workers in these Rocky Mountain fields who could be organized into one industrial union. They have a tradition in favor of militant action, and recent experience in it. They are not divided by craft pride or skill to the extent that workers are in other industries. Their divisions are largely artificial, and boss-made, with the exception of nationalities, and this difference cannot be kept alive forever. A little energetic agitating, and who knows…?

The Workers Monthly began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Party publication. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and the Communist Party began publishing The Communist as its theoretical magazine. Editors included Earl Browder and Max Bedacht as the magazine continued the Liberator’s use of graphics and art.

PDF of issue 1: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1924/v4n02-dec-1924.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1925/v4n03-jan-1925.pdf