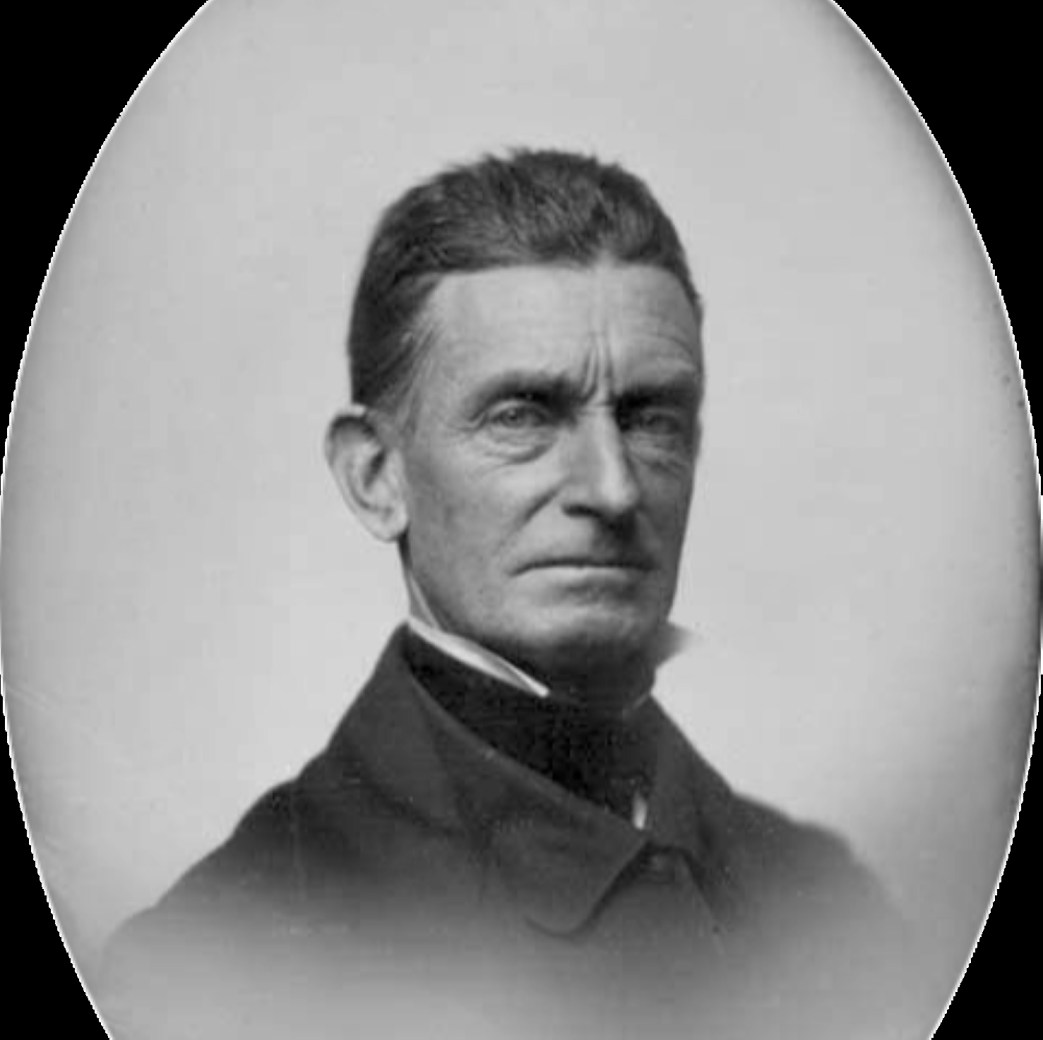

John Brown has been embraced by the left in this country since he first won notoriety in Kansas during the 1850s. Even more so, in many ways, 1859 is the birth of the modern U.S. left as Harper’s Ferry forced the question of slavery and impelled the best of the workers movement to take up the cause. Michael Gold’s influential biography was the first ‘modern’ telling of the John Brown story. Originally serialized in the Daily Worker in 1924 and printed in this pamphlet shortly after. This is its first online transcription. Gold re-introduced Brown to the generation of the Russian Revolution. Over a decade later, and in different political circumstances, Gold would co-pen the ‘Battle Hymn,’ a W.P.A.-produced play about Brown that later made it to Broadway. Whatever its history faults (much research has been done since), Gold’s book remains a valuable marker in our understanding of John Brown, who will ever remain an inspiration to the oppressed in their freedom struggle. Because of the length this will be presented in three parts. In this section Foreword, When Slavery Was Respectable, How John Brown Became an Abolitionist, Letter to Stearns, How John Brown Educated Himself, The Moulding of John Brown, Part two, part three.

‘The Life of John Brown’ Part One by Michael Gold. Haldeman-Julius Company, Girard, 1924.

FOREWORD.

John Brown’s life is a grand, simple epic that should inspire one to heroism. No one asks for dates and minute details on hearing the life of Jesus or Socrates. There are men who have proved their superiority to the pettiness of life, and who seem almost divine. John Brown is one of them. I think he was almost our greatest American. I know that he was the greatest man the common people of America have yet produced.

He did not become a President, a financier, a great scientist or artist; he was a plain and rather obscure farmer until his death. That is his greatness. He had no great offices, no recognition or applause of multitudes to spur him on, to feed his vanity and self-righteousness. He did his duty in silence; he was an outlaw. Only after he had been hung like a common murderer, and only after the Civil War had come to fulfill his prophecies, was he recognized as a great figure.

But in his life he was a common man to the end, a hard-working, honest, Puritan farmer with a large family, a man worried with the details of poverty, and obscure as ourselves. Now we are taught as school-children that only those who become Presidents and captains of finance are the successful ones in our democracy. John Brown proved that there is another form of success, within the reach of everyone, and that is to devote one’s life to a great and pure cause.

John Brown was hung as an outlaw; but he was a success, as Jesus and Socrates were successes. Some day school-children will be taught that his had been the only sort of success worth striving for in his time. The rest was dross; the personal success of the beetle that rolls itself a huger ball of dung than its fellow-beetles, and exults over it.

John Brown is a legend; but I still see him in the simple, obscure heroes who fight for freedom today in America. That is why I am telling his story. It is the story of thousands of men living in America now, did we but know it. John Brown is still in prison in America; yes, and he has been hung and shot down a hundred times since his first death. For his soul is marching on; it is the soul of liberty and justice, which cannot die, or be suppressed.

LIFE OF JOHN BROWN

WHEN SLAVERY WAS RESPECTABLE

To understand any of the outstanding men of history one must also understand something of their background. The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius persecuted and burned the primitive Christians; yet he is accounted one of the most religious and humane of historical figures, and his Meditations are commonly considered a book of the gentlest and wisest counsel toward the good life.

You cannot understand this paradox unless you know the history of the Roman state. And you cannot understand John Brown unless you understand the history of his times.

John Brown, until the age of fifty, had lived the peaceful, laborious life of a Yankee farmer with a large family. He hated war, and was almost a Quaker; had never handled fire-arms, and was a man of deep and silent affections. He was deeply religious, read the Bible daily; Christianity imbued all the acts of his daily existence.

This man, nearing his sixtieth year, assembled a group of young men with rifles and took the field to wage guerrilla war on slavery. He became a warrior, an outlaw. What drove him to this desperate stand?

I think the answer is: Respectability. There is nothing more maddening to a man of deep moral feeling than to find that slavery has become respectable, while freedom is considered the mad dream of a fanatic.

The slavery of black men had become the most respectable institution in America in John Brown’s time. It had had a dark and bloody history of a hundred years in which to become firmly rooted into American life.

There had been slavery in Europe for centuries before the discovery of America-but it was white slavery. Each feudal baron owned hordes of serfs-white farmers-who were as much a part of his land-holdings as his castles, horses and ploughs.

With the invention of printing, gunpowder and machine production the system of feudalism declined. The French Revolution helped deal it a death blow. The last country where this ancient slavery of white men was not dead was in Russia; but African slavery, the slavery of Negroes, who were heathens, and therefore could morally be bought and sold by Christians, had been reintroduced on the northern coast of the Mediterranean by Moorish traders. In the year 990 these Moors from the Barbary Coast first reached the cities of Nigrita, and established an uninterrupted exchange of Saracen and European luxuries for black slaves.

Columbus tried to introduce Indian slavery into Europe but the church forbade it, for Indians were accounted Christians when converted. The unhappy Negroes were not considered convertible; their slavery was sanctified by the church. And for the next few centuries the African slave-trade was the most lucrative traffic pursued by mankind. Black slaves were to be found in the whole vast area of Spanish and Portuguese America, also in Dutch and French Guinea and the West Indies. It was black men who cleared the jungles, tilled the fields, built the cities and roads and laid down, in their sweat and blood, the foundations of civilization in the New World. Great, jealous and prosperous monopolies were formed in this traffic of slaves; and its profits were greedily shared by philosophers, statesmen and kings.

In 1776, the American colonies were inhabited by two and a half million white persons, who owned half a million slaves. Many of the most rational and humane leaders of the Revolution saw the inconsistency of slave-holders making a revolution in the name of freedom. There was some early agitation against slavery, but the humanitarians were in a minority. Even then slavery had become respectable and profitable. It would have been easy and cheap to have freed the slaves then. It would have been the most practicable thing the young nation could have done. Not a life would have been lost; and the development of the country might have been even more rapid. But it was not done; such acts need more far-sightedness than the average man possesses.

Slavery grew by leaps and bounds, as the country was growing.

The slave trader, shrewd, intelligent and rich, kidnapped young men and women in Africa and did a huge business. His markets became the feature of every Southern town. The planters lolled at their ease, and devised ways and means of forcing their slaves to breed more rapidly. The slaves were treated as impersonally as animals. Mothers were sold away from their children, and husbands from their wives. Generations of black men died in bondage, and left their children only the sad inheritance of slavery.

The South developed an aristocrat class of indolent white men and women who looked down on all work as ignominious, and who used their minds, not in the arts or sciences, but to find new moral justifications for slavery.

Slavery was respectable. “It is an act of philanthropy to keep the Negro here, as we keep our children in subjection for their own good,’ said a Southern statesman. Slavery was moral. Even most of the respectability of the North enlisted in its defense. In 1826, Edward Everett, the great Massachusetts statesman, said in Congress that slavery was sanctioned by religion and by the United States Constitution.

The churches of almost every denomination were solidly behind slavery. The Supreme Court ruled that it was constitutional. A pro- slavery President occupied the White House, and Senator Sumner, a lonely abolitionist, was beaten down with a loaded cane on the senate floor because he dared say a brave word against the nation’s crime.

In 1838 William Lloyd Garrison founded the Liberator, first of the abolitionist journals. He said that “the constitution is a covenant with death, and an agreement with hell,” and he fought slavery with all his power. “Our country is the world, our countrymen all mankind,” was the slogan of his journal. Garrison was beaten by a mob in a northern city for his courage; and other abolitionists were tarred and feathered, lynched, and attacked by mobs of respectable northern merchants and church- goers, much as pacifists were beaten by mobs during the late war.

Slavery was respectable. Negro field hands sold for $1,000 each, and innocent black babies were worth $100 each to the white master as they suckled at a Negro mother’s breast.

To attack slavery was to attack the constitution, the church, the government, and the institution of private property. To attack respectability has always been the crime of the saviours, and respectability is the cross on which they are forever hung.

HOW JOHN BROWN BECAME AN ABOLITIONIST

In the pagan ages and in the more distant days of savagery, men were individuals. They had no social imagination. They could stand by and see another man writhe in tortures, and laugh at him. Civilization has been developing social imagination; it has been breeding more and more the type of human being who feels the suffering and injustice of another as his own.

John Brown was perhaps born with this strain in him. In 1857, when he had already plunged into his life-work, and was in the thick of bloody fights in Kansas, he sat down to write a most charming and tender letter to a little boy who was the son of one of his friends in the east. Those who think of fighters like John Brown as possessed by only a lust for battle, ought to read this letter. It reveals how soft was his heart under the grim mask of the Kansas warrior.

The letter is autobiographical. It tells how John Brown first became acquainted with the horrors of slavery, and what effect it had on his imagination.

This letter is so touching, and so remarkable for the picture it gives of John Brown’s early years, also for the picture of the man’s mature character as revealed by his own words, that I am tempted to give it in full. I shall give only parts of it, however.

THE LETTER TO MASTER HENRY L. STEARNS

“My dear Young Friend: I had not forgotten my promise to write you; but my constant care and anxiety have obliged me to put it off a long time. I do not flatter myself I can write anything that will very much interest you; but have concluded to send you a short story of a certain boy of my acquaintance; and for convenience and shortness of name, I will call him John.

“This story will be mainly a narration of follies and errors, which I hope you may avoid; but there is one thing connected with it, which will be calculated to encourage any young person to persevering effort, and that is the degree of success in accomplishing his objects which to a great extent marked the course of this boy throughout my entire acquaintance with him; notwithstanding his moderate capacity, and still more moderate acquirements.

“John was born May 9, 1800, at Torrington, Connecticut; of poor and hard-working parents; a descendant on the side of his father of one of the company of the Mayflower who landed at Plymouth, 1620. His mother was descended from a man who came at an early period to New England from Amsterdam, in Holland. Both his father’s and his mother’s fathers served in the war of the revolution; his father’s father died in a barn at New York while in the service, in 1776.

“I cannot tell you of anything in the first four years of John’s life worth mentioning save that at an early age he was tempted by three large brass pins belonging to a girl who lived in the family; and stole them. In this he was detected by his mother; and after having a full day to think of the wrong, received from her a thorough whipping.

“When he was five years old his father moved to Ohio, then a wilderness filled with wild beasts and Indians. During the long journey which was performed in part or mostly with an ox-team, he was called on by turns to assist a boy five years older, and learned to think he could accomplish smart things in driving the cows and riding the horses. Sometimes he met with rattlesnakes which were very large, and which some of the company generally managed to kill.

“After getting to Ohio he was for some time rather afraid of the Indians, and of their rifles; but this soon wore off, and he used to hang about them quite as much as was consistent with good manners, and learned a trifle of their talk. His father at this time learned to dress deer skin, and John, who was perhaps rather observing, ever after remembered the entire process of deer skin dressing, so that he could at any time dress his own leather such as squirrel, raccoon, cat, wolf or dog skins; and also he learned to make whip lashes, which brought him in some change at various times, and was useful in many ways.

“At six years old John began to be quite a rambler in the new wild country, finding birds and squirrels, and sometimes a wild turkey’s nest. Once a poor Indian boy gave him a yellow marble, the first he had ever seen. This he thought a good deal of, and kept it a good while; but at last he lost it one day. It took years to heal the wound, and I think he cried at times about it. About five months after this he caught a young squirrel, tearing off its tail in doing it; and getting severely bitten at the same time himself. He however held on to the little bob-tailed squirrel and finally got him perfectly tamed, so that he almost idolized his pet. This, too, he lost, by its wandering away; and for a year or two John was in mourning; and looking at all the squirrels he could see to try and discover Bobtail, if possible. He had also at one time become the owner of a little ewe lamb which did finely until it was about two-thirds grown, when it sickened and died. This brought another protracted mourning season; not that he felt the pecuniary loss so heavily, for that was never his disposition; but so strong and earnest were his attachments. It was a school of adversity for John; you may laugh at all this, but they were sore trials to him.

“John was never quarrelsome; but was excessively fond of the roughest and hardest kind of play; and could never get enough of it. He would always choose to stay at home and work hard, rather than go to school. To be sent off alone through the wilderness to very considerable distances was particularly his delight; and in this he was often indulged; so that by the time he was twelve years old he was sent off more than a hundred miles with companies of cattle; and he would have thought his character much injured had he been obliged to be helped in such a job. This was a boyish feeling, but characteristic, nevertheless.

“When the war broke out with England in 1812 his father soon commenced furnishing the troops with beef cattle, the collection and driving of which afforded John some opportunity for the chase, on foot, of wild steers and other cattle through the woods. During this war he had some chance to form his own boyish judgement of men and measures; and the effect of what he saw was to so far disgust him with military affairs that he would neither train nor drill, but got off by paying fines; and got along like a Quaker until his age had finally cleared him of military duty.

“During the war with England a circumstance occurred that in the end made him a most determined Abolitionist and led him to swear eternal war with slavery. John was stopping for a short time with a very gentlemanly landlord, since made a United States Marshal. This man owned a slave boy near John’s age, a boy very active, intelligent and full of good feeling to whom. John was under considerable obligation for numerous little acts of kindness.

“The Master made a great pet of John; brought him to table with his finest company and friends and called their attention to every little smart thing he said or did, and to the fact of his being more than a hundred miles from home with a company of cattle alone; while the Negro boy (who was fully if not more than his equal) was badly clothed, poorly fed and lodged in cold weather, and beaten before John’s eyes with iron shovels or any other thing that came first to hand.

“This brought John to reflect on the wretched, hopeless condition of fatherless and motherless slave children; for such children have neither fathers or mothers to protect and provide for them.

“He sometimes would raise the question in his mind: Is God, then, their father?”

HOW JOHN BROWN EDUCATED HIMSELF

There are other matters treated in this long and charming letter, written by an outlaw 57 years old, to a boy of twelve. One detail that is important is the analysis of his own character. John Brown says his father early made him a sort of foreman in his tanning establishment, and that though he got on in the most friendly way with everyone, “the habit so early formed of being obeyed rendered him in after life too much disposed to speak in an imperious or dictating way.” John Brown was ever humble, and severely chastised his own faults, but this habit of being a leader served him in good stead, and made him the born captain of forlorn hopes he later became.

Another detail that interests us is his account of his early reading. Working-class Americans, and they are the majority of the nation, do not go to the high schools and universities. Neither did John Brown. But they can read history, as he did at ten years, and they can study and make themselves proficient in some field, as he made a surveyor of himself by home study. He also read passionately, he says, the lives of great, good and wise men; their sayings and writings; the school of biography that seems to have nurtured so many great men. John Brown never went to school after his childhood; but he became an expert surveyor, he learned the fine points of cattle breeding and tanning, he was a student of astronomy, he knew the Bible almost by heart, he studied military tactics later in life, he was familiar with the lives and times of most of the great leaders of mankind, and best of all, he knew how to stir men to great deeds, and lead them in the battle.

Great men do not need to own a college diploma; they teach themselves, they are taught by Life.

How meaningless college degrees would sound if attached after the names of Brutus, Pericles, Socrates, Caius Gracchus, Buddha, Jesus, Wat Tyler, Jefferson, Danton, William Lloyd Garrison!

As for instance: Jesus Christ, D.D.; Robert Burns, M.A.; Victor Hugo, B.S.; John Brown, Ph.D.! How superfluous the titles of man’s universities, when Life has crowned the student with real and greener laurels! Yes, there are many things not taught in the colleges!

THE MOULDING OF JOHN BROWN

And so by his own pen, we have had illuminated for us the life of John Brown up to his twentieth year. We see him, a big, strong boy, fond of hard work, capable in all he put his hand to, a young man bred in the hard college of life in an early pioneer settlement. He was fond of reading good books, and improving his mind; he was rather shy, and yet filled with an extraordinary self-confidence, which made him a born leader, one who could show the way to men older than himself, and command them, and himself, in the straight line of duty.

The subsequent life of John Brown cannot be understood unless one knows all the environmental forces and the heredity that went to mould him. John Brown, a Puritan in the austerity of his manner of living, the narrow yet burning reality of his vision, and the hard- ships he later underwent, came of a family of American pioneers. To John Brown life from the outset meant incessant strife, first against unconquered nature, then in the struggle for a living, and finally in that effort to be a Samson to the pro-slavery Philistines in which his existence culminated.

At twenty John Brown married Dianthe Lusk, a plain but quiet and amiable girl, as deeply religious as her young husband, and as ready as he to assume all the serious burdens of life.

He was working in his father’s tanning establishment at this time, at Hudson, Ohio. But in May, 1825, John Brown moved his family to Richmond, near Meadville, Pennsylvania, the first of his many moves for he was imbued with a deep restlessness, the hunger of the pioneer for virgin lands and new enterprises.

Here, with his characteristic energy, he cleared twenty-five acres of timber land, built a fine tannery, sunk vats, and in a few months had leather tanning in all of them. Like his father, Owen Brown, John was of a marked ethical and social nature. He proved of great value to the new settlement at Richmond by his devotion to the cause of religion and civil order. He surveyed new roads, was instrumental in building school houses, procuring preachers, “and encouraging anything that would have a moral tendency.” It became al- most a proverb in Richmond, so an early neighbor records, to say of a progressive man that he was “as enterprising and honest as John Brown, and as useful to the county.’

In Richmond the family dwelt for ten years. John Brown raised corn, did his tanning, brought the first blooded stock into the county, and became the first postmaster. Here, also, at Richmond, the first great grief came into John Brown’s life, to school him in that stoicism that later made him the hero of a great cause. A four year old son died in 1831, and the next year his wife, Dianthe, died after having lived and worked beside him like a good, faithful woman for twelve years, giving birth to seven children in that time, five of whom grew to vigorous manhood and womanhood.

Nearly a year later John Brown was married for the second time, to Mary Anne Day, daughter of a blacksmith. She was then a large, silent girl of sixteen, who had come to John Brown’s home with an older sister to care for his children after his wife’s death. He quickly grew fond of the young pioneer girl; one day he gave her a letter offering marriage. She was So overcome that she dared not read it. Next morning she found courage to do so, and when she went down to the spring for water for the house, he followed her and she gave him her answer there.

Mary Brown was the best wife a John Brown could have found. She had great physical ruggedness, and she bore for her husband thirteen children, seven of whom died in childhood, and two of whom were killed in early manhood at Harper’s Ferry. She did more than her full share of the arduous labor of a large pioneer household, and she endured hardships like a Spartan mother. She was strong; and she had a noble and unflinching character. It was only a heroic woman such as this who could have been the wife of a hero; who could have given husband and sons cheerfully to the cause of abolition, and been so silent and brave even after their death.

John Brown worked hard; he had no vices, he was honest and painstaking, but somehow success in business always eluded him. This was another of the griefs of his life. He blamed himself for his failures, but it was really not his fault. It requires a real worship of money to make one a business success, and John Brown never took money as seriously as it demands of its lovers. After ten years in Pennsylvania, of much hard work with little results, he moved to Franklin Mills, in Ohio, where he entered the tanning business with Zenas Kent, a well-to-do business man of that town. Here he also became involved in a land development scheme that was ruined by a large corporation’s maneuvers. He was so deeply involved in this and other ventures that in the bad times of 1837 he failed. In 1842 he was again compelled to go through bankruptcy proceedings.

In after years John Brown explained these failures to his oldest son as the result of the false doctrine of doing business on credit.

“Instead of being thoroughly imbued with the doctrine of pay as you go,” he wrote, “I started out in life with the idea that nothing could be done without capital, and that a poor man must use his credit and borrow; and this pernicious doctrine has been the rock on which I, as well as many others, have split. The practical effect of this false doctrine has been to keep me like a toad under a harrow most of my business life. Running into debt includes so much evil that I hope all my children will shun it as they would a pestilence.”

John Brown never gave up in despair anything he had attempted; his business failures bruised him sorely, but he arose each time like a rugged wrestler and began a new endeavor. In 1839, at one of his darkest periods, he began a sheep growing and wool marketing venture in which he engaged for many years, going into partnership with Simon Perkins, a wealthy merchant of Akron, Ohio. This partnership was the longest and final one of Brown’s business career.

So that is how one must think of Brown, too; not only as the consecrated, almost inhuman battler and martyr, but also as the sane, plodding, patient farmer, tanner, surveyor, real estate speculator, and practical shepherd. He was a tall, spare, silent man, terribly pious, terribly honest, a good neighbor and community leader, and the father of a large family of sons and daughters-a patriarch out of the Bible, tending his flocks and gathering about him a tribe of young and stalwart sons.

He was a typical pioneer American of those rough days in the settling of the middle west. He had no time for frivolity, though there was a grim humor in the man; he brought his children up strictly, yet with a justice that made them all love, revere and respect him until the end; and he had his share of those private sorrows that crush so many men; his first beloved wife had died, with an infant son; he had failed in business; and he had lost by death no less than nine children, three of whom perished in one month in those hard surroundings, and one of whom, a little daughter, was accidently scalded to death by an elder sister. These deaths hurt John Brown cruelly, for though stern and stoic, he was a fiercely tender father; all his affections were fierce, though inexpressible and deep, as a lion’s.

“I seem to be struck almost dumb by the dreadful news,” he wrote his family, when he heard of this accident. “One more dear little feeble child I am to meet no more till the dead, small and great, shall stand before God. I trust that none of you will feel disposed to cast an unreasonable blame on my dear Ruth on account of the dreadful trial we are called to suffer. This is a bitter cup indeed; but blessed be God; a brighter day shall dawn; and let us not sorrow as they who have no hope.”

The Browns had made at least ten moves in the years from 1830 to 1845, and John Brown had engaged in no less than seven different Occupations. But always, under the business man and farmer, there had been the solemn philosopher brooding on God and the mystery and terror of life; and always, under the sober father and citizen, there had been planning and brooding and suffering keenly the tender humanitarian, the Christ-like martyr, the relentless fighter who would finally pay with his life to strike a blow at Slavery, “that sum of all villainies.”

In this patriarchal farmer of the middle west, Freedom was forging and sharpening a terrible weapon that was some day to be turned against Tyranny. Quietly, in peaceful surroundings the work was being done; no one knew the fire in this man, least of all himself.

PDF of full book: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/dul1.ark:/13960/s24541z1bsw