Theresa Malkiel’s marvelous essay on the ‘Uprising of 40,000’ strike of New York City, largely immigrant, shirt waist workers that transformed the labor movement. A classic.

‘Courage of Women and Girls Won Against the Union Crushers’ by Theresa Malkiel from the Chicago Daily Socialist. Vol. 4 No. 105. February 26, 1910.

It was only seven in the morning and the great East Side had not fully awakened from the night’s sleep when thousands of women young and old of varied types and nationalities, coming from every corner of the metropolis, crowded around 151 Clinton street.

Apprised of the fact Mr. Shindler, the secretary of the Waist Makers’ union, worn out from a sleepless night, his hair disheveled, shirt collar unbuttoned, ran down to meet the advance lines of the incoming army.

35,000 Strong

From that hour of the morning until late at night they kept coming. Thirty-five thousand young girls and women old enough to be their grandmothers responded to the call to arms sent out the previous night by a little shop girl. It was a great mystery how they were apprised of it so soon, and still greater mystery that they came without a protest. These women, who had gone through life as in a trance, had with one gigantic effort torn asunder the fetters of ancient custom and tradition determined for this once to wage an earnest battle for the right to live.

Those tired out factory women who had to rise long before seven in the morning in order to feed the machine with dozens upon dozens of sleeves, bodies and hundreds of yards of tucks, driving the insatiable monster at a nerve and body racking speed, continuing steadily and aimlessly this stupefying, soul hardening mad rush that they may eke out five, six and at times only three dollars a week. These women had realized, at last, the horror of their condition and were now rebelling against it.

A Vast Concord

It seemed that the very spontaneity of the strike brought about a revolution in their minds, which alone could Recount for their great unanimity. For, if their walk-out was accomplished on the impulse of the moment, while spurred on by the enthusiasm of the few, their grievances could be traced to the time when shirtwaist making first became a factor in the industrial field. The trade originated about two decades ago when, with the general exodus of woman from the home into the turmoil of the Industrial and business world, there came the great change in her attire. The universal custom of the tight fitting, well boned, long trained dress had to give way to the short walking skirt and comfortable, yet neat, shirtwaist.

For a time shirtwaist making as a trade did not prosper. The few middle class men who had ventured into the business found it for from profitable. the demand instead of increasing. was falling off at an alarming rate and. naturally enough, the waistmakers had to bear the greatest share of the burden.

The First Union

It was then that a portion of the thousand workers in the trade, mostly men, assembled on the top floor of 9 Rutgers street and organized the first waistmakers’ union.

For the first few months the waistmakers rallied around the new organization. A number of small strikes were fought and won. The membership increased rapidly and those at the head of the union hoped in time to gain control of the entire trade.

But after a year or two of Indecision, womanhood concluded that the walking skirt and shirtwaist had come to stay. Business in this line boomed up to the highest pitch. The demand for waists grew larger than the supply. Prices were raised, work was steady, wages good and, for a time, the workers considered themselves the masters of the situation.

The panic of 1898 came as a rude shock to their fancied security. The failure of numerous business houses left thousands of women minus employment, they swarmed to the shops and factories offering to do a man’s work for half his wage. The employers affected by the general depression were anxious to curtail expenses and eagerly supplanted their male waistmaker with young girls willing to work for less.

Became Sweaters

The discharged workers flocked to the union for redress, but the latter was unable to combat the growing evil. Then the idle men realized that their future existence would depend on the survival of the most unscrupulous and, with the heartlessness born of despair, they turned into human vultures.

Every fifth man discharged became a sweater. Some placing a few machines in their small, ill-ventilated homes, others contracting to do the work inside the factory, accepting the low wages offered and paying much less to the hands employed by them.

The sweater divided the waist into many sections, so that it could be made by unskilled labor and hired girls of fifteen to do the work. These young and healthy children entered the factories with the atmosphere of childhood still clinging to them, but they were doomed soon to lose youth, health and ambition in the mad struggle for a miserable existence.

Every incoming season saw a decrease in prices until finally a whole waist was made for four cents. To earn a dollar a girl had to make ten dozen pair of sleeves, eight hundred yards of tucks or five dozen bodies. The average worker succeeded but seldom in earning a dollar a day at a time when work was plenty.

All Women Need

This decline in prices was not due to a decreased demand or lessened value of product the shirtwaist had become a necessary adjunct in every woman’s wardrobe. Beginning with the thirty- nine-cent waist of the shop girl, who herself received only four cents for its making, to the dainty lingerie creation of the society lady, which is valued at many dollars and paid less for comparatively than the cheap waist.

During these years of rise and decline in the earnings at waistmaking the union kept up only a semblance of existence. This was partially due to the fact that the army of waistmakers, whose numbers had risen to forty-seven thousand, consisted mostly of women.

The employers were fully aware of the elements that went to fill their work rooms and lived in security. Nay, for further assurance they had concocted a scheme of binding the workers to their respective work rooms. They had organized shop clubs, the dues paid in to the treasury by each worker were to serve as a sick benefit fund. But each member forfeited his money upon joining the union or leaving the work room for another place.

The workers rebelled against this new despotism, it was more than even their meek characters could stand. Thus It happened that the last winter season saw the first skirmishes of the later conflagration. The workers of Rosen Brothers were the pioneer rebels. They won their fight and their example was followed by fifty Russian girls employed by the firm of Leiserson & Co. and a number of other smaller concerns who were in time fortunate, except the Leiserson girls, to gain a recognition of the union and a better scale of wages. The organization revived once more, its membership was counted by the hundreds, many of the shops being on the fair list.

Labor Makes War

One day in the latter part of September the union office was besieged by eight hundred waistmakers–the locked out employes of the Triangle Waist company. Organized labor welcomed these shopless waifs into its ranks, looked into their grievance and declared war against the firm.

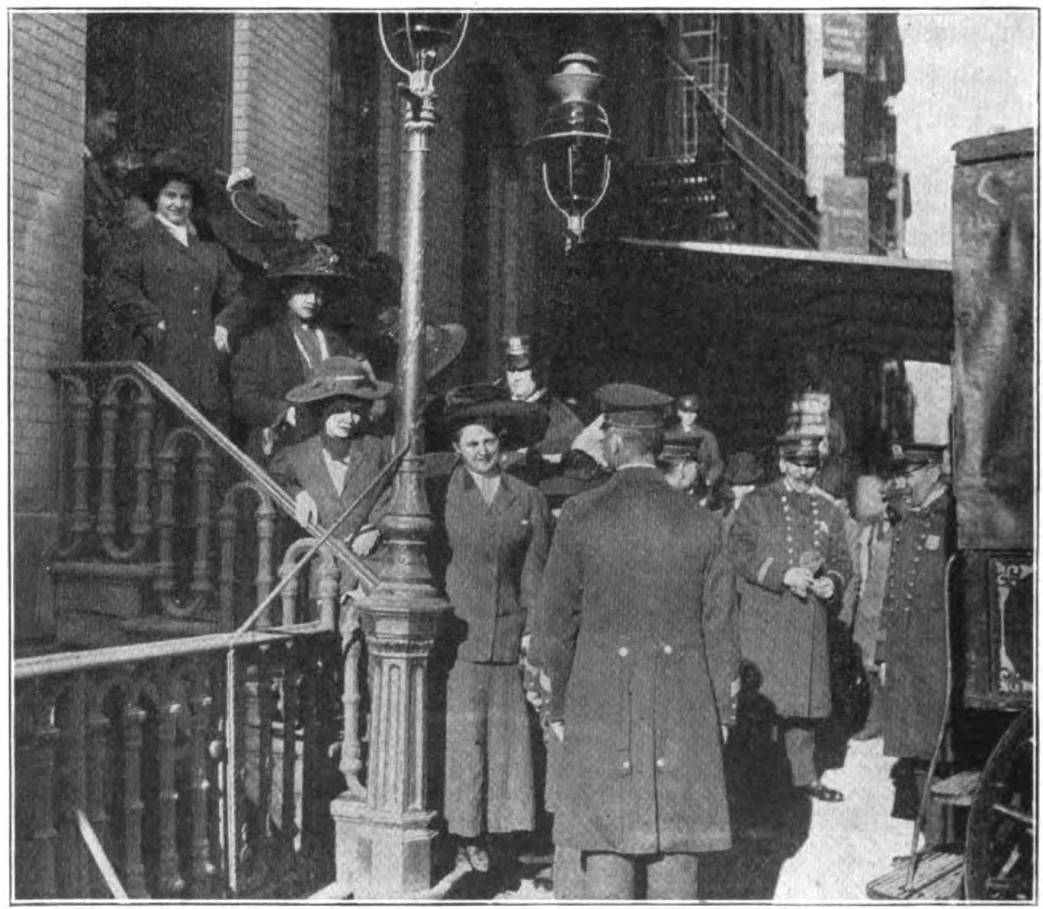

The locked out workers were organized into picketing squads and stationed near the factory to persuade others from taking their places. The unfortunate guards did not realize what confronted them. Their former employers hired thugs who beat and insulted. them, afterwards handing them over to the police for arrest. The firm seemed to have a great deal of influence, when the abused girls were brought before. the judges; they were censured and fined without being given an opportunity to state their side of the case.

Aroused by the terrible injustice, a number of society women and college girls, members of the Woman’s Trade Union league, took the place of the exhausted pickets. Thus it happened one morning that a city magistrate was shocked to find the prisoner before him was none other than the president of the Women’s Trade Union league, an heiress and society leader. She was, of course, discharged.

Young Girl Abused

Next in line came another picket, Lena Barsky, a modest, childish looking girl of sixteen. That morning while talking to another girl she felt herself suddenly in the grip of a pair of strong hands; a torrent of vile epithets was showered upon her and before she had a chance to realize what had happened she was thrown into a patrol wagon, brought to court and arraigned before the kind magistrate. The latter without taking note of the youthful prisoner fined her ten dollars.

As the weeks passed by, the war between the employers and their workers grew harsher, the persecuted lock outs suffered terrible hardships. The incoming season brought with it a new reduction in prices. Some of the firms employing union labor threatened to break their agreements: the entire trade was in a ferment. Unable to cope with the conditions, the union called the since then famous mass meeting that took place on Monday, Nov. 22. Long before the hour of opening the eager workers crowded around the doors of Cooper Union anxious to hear the final word from the lips of Samuel Gompers. Tired and exhausted from the day’s work they clung close to one another, the evening was cold and their clothes threadbare. As the fingers of the big clock pointed toward eight their lusterless Kaze gave way to a brighter expression, within was warmth and there they would hear the words of the oracle.

Gompers Speech

At last, rushing, pushing and stepping on each other’s toes, they took all the available seats and covered every inch of ground in the large auditorium. In another few minutes he came. They greeted him with a war yell that was heard far into the street.

Mr. Gompers walked to the rostrum, glanced at the audience and suppressed a sarcastic smile. He was facing row upon row of be-ribboned, be-feathered and be-flowered hats worn by the young girls in the audience.

A moment later he was talking to them, talking about his experience at the convention, about organized labor abroad and many other things. The tired heads bent to one side, the weary eyes closed-the audience was disappointed. Suddenly the ear caught the familiar slogan “waistmakers.” Mr. Gompers was saying that he could not dictate to the waist makers any specific method of procedure, for they alone knew the real conditions they were laboring under.

A General Strike

“I’m tired of this! I move that we call a general strike!” came a high pitched feminine voice from the audience.

“Seconded!” arose the shouts from all over the hall.

The hour had come, the bent heads were raised, the weary eyes were closed no longer–they were ready for the call. In another minute the motion was adopted by acclamation and Clara Lemlich, the maker of it, became the woman of the day.

The executive committee of the union spent many sleepless hours that night, planning the campaign. The prospect was not encouraging. The employers were, as a rule, shrewd business men with little or no scruples so far as their workers were concerned. They owned the tools of production and were well supplied with money. On the other hand, the majority of the waistmakers were young. inexperienced girls more suited for the school bench. They were penniless, had never belonged to any labor organization, were of different races and nationalities, did not know what solidarity of interests meant and were not prepared to make a great sacrifice for a cause.

But early the next morning, these men were confronted by a brave, powerful army that had since surpassed all expectations. The mystery of it all was heightened by the fact that the employers, astonished by the suddenness of the blow, had urged their workers to remain, promising them more favorable conditions and steady employment.

The few men in the little office of the union were completely overwhelmed and sent out a call for help. It was answered from different quarters. The members of the Woman’s Trade Union league came at an express speed. They were followed by walking delegates from the different trades, members of the Socialist party, individual settlement workers and suffragists. All anxious to form that wild mob into an organized body. Every available hall in the neighborhood was engaged by the union. The crowd was subdivided into groups belonging to the same work room and the enlistment of the soldiers that were to constitute the army of the waistmakers commenced in earnest.

A Great Hope

The organizers were bewildered by the enthusiasm displayed by the girls, so suddenly lifted from the monotonous drudgery of the work bench and placed face to face with the grim necessity of waging battle. When notes were compared and books added up that evening, it was found out that nineteen thousand were enrolled as members. Thirty-six hours after the strike was decided upon, every factory within the precincts of greater New York had some of its workers within the ranks of the strikers.

Hence the assertion: Of all the big and small strikes that were ever fought within the boundaries of our Metropolis, there was never a similar uprising. The waistmakers’ strike was a sign of the times, a woman’s rebellion against the long and persistent oppression of ages.

The officers of the union remained at their post day and night, nor were they the only ones. In this, like any other battle, the silent heroes were numerous. There was work for all. The information bureau was steadily besieged by strikers, whose inquiries had to be answered and demands satisfied. The smaller employers, pressed by the necessity of keeping their capital in circulation, hurried to the headquarters ready to sign agreements, thus requiring a special force to attend them, for during the first day of the strike four thousand workers went back under union conditions. Speers and organizers were in great demand, the law committee, too, was kept busy.

To Crush Girls

Unable to break the striking lines by individual promises and threats, the employers assembled at the Hoffman house and organized the Employers’ Protective Association. Its sole object was to crush the waistmakers’ union. They resorted to the most outrageous devices, hired thugs, ruffians and prostitutes who abused and insulted the defenseless girls. They secured the good graces of the police and the latter arrested the pickets on the least pretext. The police judges, too, were very prejudiced against the young rebels and fined them heavily.

Broken in health by the years of super-human toll in the factories, bowed under the weight of their suffering, enraged by the inhuman treatment recorded them, these prospective mothers of our future citizens thronged around the only place where they still hoped to find protection–the union office. Day in day out from morn till night their tales of woe were poured into the ears of the volunteer assistants: the complaints come in faster than the clerks could take them down. Demolished wearing apparel, pulled out hair, knocked out teeth, broken noses, swollen faces and bruised heads were there in plenty. Pathetic, pitiful pleas for assistance were a constant occurrence, but the silent sufferers were there, as well.

Enemies of Humanity

The names of Judges Cornell and Harris were steadily upon the lips of the strikers, for the former two had openly placed themselves on the side of the employers and punished the girls, regardless of their guilt or innocence. Judge Harris, sitting in the night court. had subjected the girls to great indignities, keeping them locked up for hours alongside of drunken depraved women, who tried to avenge their own suffering upon the young girls.

The strikers were appalled by the ordeals they were compelled to undergo and angrily remonstrated with the union officials, demanding redress and protection, but even in their angry remonstrances there was always a note of despair and suffering, for the third week of the strike had already found the majority on the point of starvation. A few hours with them and their sorrows, glance at their squalid homes and one did not need any further proof that their demands were timely.

They did not ask for luxuries or riches, only a little more bread, for at times there was more than one mouth to share it. They wanted a respite from their weary labors and union protection. They needed it badly- these lone children, without a mother country. It was only natural that their sad plight should arouse a great deal of sympathy. It was inevitable for the human heart to ache at the contemplation of their life long misery.

Pathetic Indeed it was to see them in the half dark meeting halls huddling to the little stove, telling each other of their experience while on picket duty, relating their sorrow and tribulations, seasoning their words with torrents of tears and at times shouts of laughter.

They were still young and the joy of living was not yet all crushed out of them. This was clearly expressed by the occasional dances that took place amidst all the sordid surroundings. But at the sound of the chairman’s gavel a hush fell over the entire assembly and to the amazement of the outsider the gay dancers would bend their heads in grave consultation over the means of carrying on a further campaign.

Unions Won

The fourth week of the struggle found fourteen thousand back at work under union conditions, but fully as many were still swarming the hall of the great East Side, crowding the police courts and landing even at the workhouse.

At this juncture the flag of truce was raised, but the arbitration committee failed to accomplish its mission–the employers were false to their promise of arbitration. They would not hear about the recognition of the union. And this was the most vital point that the workers hoped to gain. The variety of styles, and their constant change necessitates a frequent readjustment of the wage scale, which the union alone. could guard from abuse and exploitation.

The suffering strikers assembled at Grand Central Palace and after listening earnestly to the report of their arbitrators, decided to remain on strike regardless of the terrible hardships that they were undergoing hardship and suffering seemed to be their lot; they had become used to it almost from the very cradle.

$6 a Week

Today in view of the high prices. paid for the necessaries of life it is hard to comprehend how a person could get along in this big city on five or six dollars a week, and these earned only seven or eight months of the year. The suspicious mind may conclude that there is more than one way by which a woman could earn a living, but it is only necessary to become acquainted with their struggles, to examine the food they are eating, the homes they are inhabiting and the pleasures they are enjoying to understand how they manage it.

The more wonderful the courage they were displaying all along. When sent to the workhouse they returned with a smile on their faces, hiding deep in their hearts the abuse and indignities that they had to undergo there. Ill-clad and hungry they went out in the bitter cold to sell the special edition, that all may get some benefit. And when offered at the headquarters of the league hot coffee, bought on the money received for these very papers they said: “Not yet: give the money to those who are sick, or have small children to feed.”

Learned Fast

They were no longer the same girls who had left the factories but a few weeks ago. During these weeks of enforced idleness they were learning things and thinking thoughts they knew nothing about before the strike. A new world opened before them, their horizon broadened and they came to live with and for one another. It was evident that these little daughters of the people had a great amount of natural intelligence which remained in a dormant state, but at the first given opportunity they were exercising it with a remarkable sagacity.

But with every new victory for the union, with every other display of courage and initiative on the part of the strikers, the enemy devised a new method of torture. When only seven thousand were left on the battle field agents of the employers were sent to the homes of the strikers during the latter’s absence, instigating the downhearted, suffering parents against their own children. With the result that the unfortunate girls were not only abused by thugs and the police, but in their own homes by their fathers and brothers who did not see the necessity of their striking.

The Cry for Bread

And still the girls stood out. Then a new settlement Was proposed by which the employers promised to give in to all the demands of their workers but the recognition of the union. The strike had been going on for six weeks, most of the strikers were destitute, the union treasury was exhaust- ed by the heavy fines and occasional benefits, the officers of the union were tired out and could no longer witness the terrible suffering of the men, women and children who crowded their office daily asking for a little help to still their hunger. The cry for bread rose louder and louder, from early morning until late at night people were crowding every floor of 151 Clinton street, trying to gain admittance to the office where benefits were being paid out. Hundreds of strikers were ill in bed either from colds caught while on picket duty or from beatings and imprisonment.

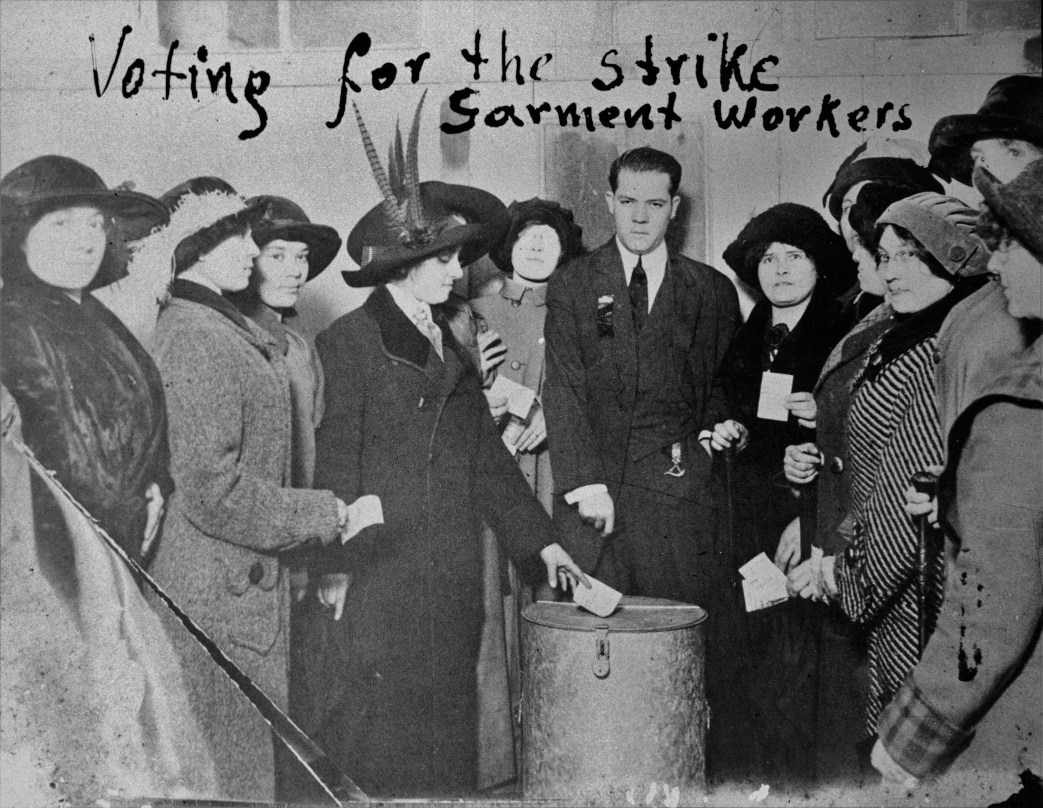

It seemed that a gloom and despondency had fallen over all. Those were the conditions when the union officers decided to call a number of meetings: in order to take a referendum upon the last proposition of the enemy.

It was not hard to get them to come to any meetings, but on that day every single man and woman involved in the strike, whether well or ill, put in an appearance. The halls were overcrowded, people stood on window sills, tables and hung onto the banister. “Somebody wants to sell us out” was heard now and then, when the speakers happened to utter a word favorable to the opposition, and when finally the chairman put the motion before them for their vote they voted it down unanimously.

Labor Aided

Their undaunted bravery aroused the Interest of organized labor and assistance started to come from all sides. The season had by this time reached a time when orders were to be delivered without delay and gradually victory was becoming a certainty. The Employers’ Protective association could not protect its members for they had deserted their ranks and signed agreements with the union. When the battle was already drawing to an end the remaining employers resorted to the last means of defense–they took out an injunction against a number of women members of the Trade Union league. The latter laughed at the threat of arrest for contempt of court; they were fearless as the girls themselves, and went on with their wonderful, inestimable assistance.

The end of the eleventh week saw the remaining thirteen employers, comprising 1,000 girls, give in and sign their agreements in a body.

There is still one phase of the strike that had been left in the dark: From the very first the seven or eight thousand men involved did not take the right standard. And all along the girls had this unnecessary evil to combat. Men hid behind women’s skirts, playing coward and deserter at every opportunity.

The girls have proven in spite of all the obstacles in their way that they could plan, fight and conquer. What effect this struggle will have on the industrial status of woman only history will tell. But woman will surely benefit by the experience gained and lessons learned.

The Chicago Socialist, sometimes daily sometimes weekly, was published from 1902 until 1912 as the paper of the Chicago Socialist Party. The roots of the paper lie with Workers Call, published from 1899 as a Socialist Labor Party publication, becoming a voice of the Springfield Social Democratic Party after splitting with De Leon in July, 1901. It became the Chicago Socialist Party paper with the SDP’s adherence and changed its name to the Chicago Socialist in March, 1902. In 1906 it became a daily and published until 1912 by Local Cook County of the Socialist Party and was edited by A.M. Simons if the International Socialist Review. A cornucopia of historical information on the Chicago workers movements lies within its pages.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/chicago-daily-socialist/1910/100226-chicagodailysocialist-v04n105.pdf