Sergey’s Stepniak’s invaluable collection of biographies of his contemporary fellow Narodniks, 1882’s ‘Underground Russia,’ was serialized by Friends of Soviet Russia in 1922 and introduced Russia’s long, heroic revolutionary past to a new generation. Sophia Perovskaya played a central role in the Mach, 1881’s assassination of Tsar Alexander II by the ‘People’s Will.’ And payed for it with her life. Renowned in her time, and revered for her stoic self-sacrifice, Perovskaya’s person loomed large over subsequent Russian history.

‘Sophia Perovskaya, Organizer and Terrorist’ by Stepniak from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 7 No. 3. August 1, 1922.

The present installment of Stepniak’s “Under ground Russia” gives a portrait of Sophia Perovskaya, whose heroism and greatness of spirit have given her a place for all time in Humanity’s Hall of Fame.

SHE was beautiful. It was not the beauty which dazzles at first sight, but that which fascinates the more, the more it is regarded.

A blonde, with a pair of blue eyes, serious and penetrating, under a broad and spacious forehead. A delicate little nose, a charming mouth, which showed, when she smiled, two rows of very fine white teeth.

It was, however, her countenance as a whole which was the attraction. There was something brisk, vivacious, and at the same time, ingenuous in her rounded face. She was girlhood personified. Notwithstanding her twenty-six years, she seemed scarcely eighteen. A small, slender, and very graceful figure, and a voice as charming, silvery, and sympathetic as could be, heightened this illusion. It became almost a certainty, when she began to laugh, which very often happened. She had the ready laugh of a girl, and laughed with so much heartiness, and so unaffectedly, that she really seemed a young lass of sixteen.

She gave little thought to her appearance. She dressed in the most modest manner, and perhaps did not even know what dress or ornament was becoming or unbecoming. But she had a passion for neatness, and in this was as punctilious as a Swiss girl.

She was very fond of children, and was an excellent schoolmistress. There was, however, another office that she filled even better: that of nurse. When any of her friends fell ill, Sopa was the first to offer herself for this difficult duty, and she performed it with such gentleness, cheerfulness, and patience, that she won the hearts of her patients, for all time.

Yet this woman with such an innocent appearance, and with such a sweet and affectionate disposition, was one of the most dreaded members of the Terrorist party.

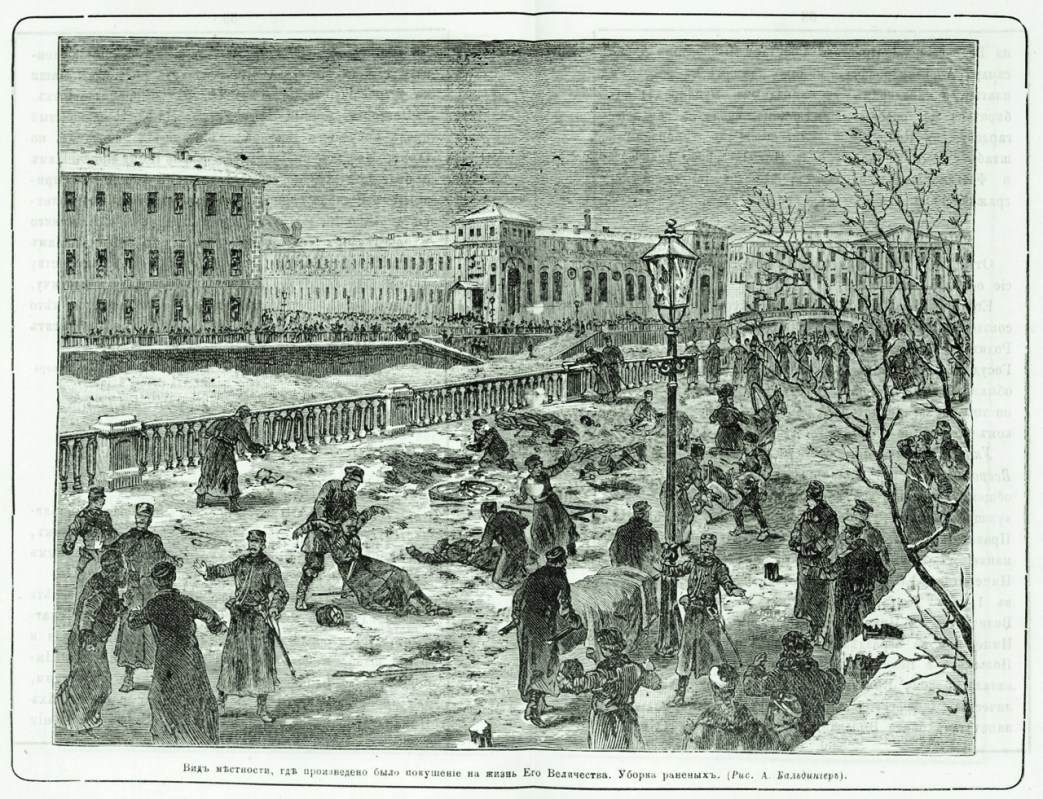

It was she who had the direction of the attempt of March 13th; it was she, who, with a pencil, outlined on an old envelope the plan of the locality, who assigned to the conspirators their respective posts, and who, on the fatal morning, remained upon the field of battle, receiving from her sentinels news of the Emperor’s movements, and informing the conspirators, by means of a handkerchief, where they were to proceed.

What Titanic force was concealed under this serene appearance? What qualities did this extraordinary woman possess?

She united in herself the three forces which of themselves constitute power of the highest order: profound and extensive talents, an enthusiastic and ardent disposition, and, above all, an iron will.

Sophia Perovskaya belonged, like Kropotkin, to the highest aristocracy of Russia. The Perovskys are the younger branch of the family of the famous Rasumovsky, the morganatic husband of the Empress Elizabeth, daughter of Peter the Great, who occupied the throne of Russia in the middle of the 18th century (1741-1762). Her grandfather was Minister of Public Instruction; her father was Governor-General of St. Petersburg; her paternal uncle, the celebrated Count Perovsky, conquered for the Emperor Nicholas a considerable part of Central Asia.

Such was the family to which this woman belonged who gave such a tremendous blow to Tsarism.

Sophia was born in the year 1854. Her youth was sorrowful. She had a despotic father, and an adored mother, always outraged and humiliated. It was in her home that the germs were developed of that hatred of oppression, and that generous love of the weak and oppressed, which she preserved throughout her whole life.

The story of her early days is that of all the young in Russia, and, at the same time, of the revolutionary party. To relate it would be to present in a concrete form, what I have narrated in an abstract form in my preface.” For want of space I can only, however, indicate its chief features.

Sophia Perovskaya commenced, like all the women of her generation, with the simple desire for instruction. When she had entered her fifteenth year, the movement for the emancipation of woman was flourishing, and had even impressed her eldest sister. Sophia also wished to study, but as her father forbade her, she, like so many others, ran away from home.

Concealed in the house of some friends, she sent a messenger to parley with her father, who, after having raged in vain for some weeks, endeavoring to find his daughter by means of the police, ended by coming to terms, and consenting to provide Sophia with a passport. Her mother secretly sent her a small sum. Sophia was free, and began to study eagerly.

What, however, did the Russian literature of that period impart to her? A bitter criticism of our entire social order, indicating Socialism as the definite object and the sole remedy. Her masters were Chernyshevsky and Dobroliuboy—the masters that is, of the whole modern generation. With such masters eagerness to acquire knowledge quickly changed in her into eagerness to work according to the ideas derived from what she had read. The same tendency arises spontaneously in many other women who are in the same position. Community of ideas and aspirations develops among them a feeling of profound friendship, and seeing themselves in numbers inspires them with the desire and the hope of doing something.

In this manner we have a secret society in embryo; for in Russia everything that is done for the welfare of the country, and not for that of the Emperor, has to be done in secret. Sophia Perovskaya became intimate with the unfortunate family of the Kornilov sisters, the nucleus from which was developed, two years afterwards, the Circle of the Chaikovsti, which I have several times mentioned. Perovskaya, together with some young students, among whom was Nicholas Chaikovsky, who gave his name to the future organization, was one of the first members of this important Circle, which at first was more like a family gathering than a political society.

The Circle, which at first had no other object than that of propaganda among the young, was not a large one. The members had always to be admitted unanimously. There were no rules, for there was no need of any. All the decisions were always taken by unanimity, and this not very practical regulation never led to any unpleasant consequences or inconvenience, as the reciprocal affection and esteem among the members of the Circle were such that what the genius of Jean Jacques Rousseau pictured as the ideal of human intercourse was attained; the minority yielded to the majority, not from necessity or compulsion, but spontaneously from inward conviction that it must be right.

The relations between the members of the Circle were the most fraternal that can be imagined. Sincerity and thorough frankness were the general rule. All were acquainted with each other, even more so, perhaps, than the members of the same family, and no one wished to conceal from the others even the least important act of his life. Thus every little weakness, every lack of devotion to the cause, every trace of egotism, was pointed out, underlined, sometimes reciprocally reproved, not as would be the case by a pedantic mentor, but with affection and regret, as between brother and brother.

These ideal relations, impossible in a Circle comprising a large number of persons united only by the identity of the object they have in view, entirely disappeared when the political activity of this Circle was enlarged. But they were calculated to influence the moral development of the individual, and to form those noble dispositions and those steadfast hearts which were seen in Kuprianov, Cherushin, Alexandra Kornilova, Serdinkov, and so many more, who in any other country would have been the honor and glory of the nation. With us, where are they? Dead; in prison; fallen by their own hands; entombed in the mines of Siberia, or crushed under the immense grief of having lost all—everything which they held most dear in life.

It was among these surroundings, austere and affectionate, impressed with a rigorism almost monastic, and glowing with enthusiasm and devotion, that Sophia Perovskaya passed the first three or four years of her youth, when the pure and delicate mind receives so readily every good impression; when the heart beats so strongly for everything great and generous; it was among these surroundings that her character was formed.

Perovskaya was one of the most influential and esteemed members of the Circle, for her stoical severity towards herself, her indefatigable energy, and, above all, for her greater abilities. Her clear and acute mind had that philosophical quality, so rare among women, not only of perfectly understanding a question, but of always seizing it in its philosophical connection with all the questions dependent on it, or arising out of it. Hence arose a firmness of conviction which could not be shaken, either by sophisms or by the transient impressions of the moment, and an extraordinary ability in every kind of discussion—theoretical and practical. She was an admirable “debater”, if I may use the word. Always regarding a subject from every side, she had a great advantage over her opponents, as ordinarily subjects are regarded by most people from one side alone, dictated by their dispositions or personal inclinations. Sophia Perovskaya, although of the most ardent temperament, could elevate herself by the force of her intellect above the promptings of feeling, and saw things with eyes which were not deceived by the bias of her own enthusiasm. She never exaggerated anything, and did not attribute to her activity and that of her friends greater importance than they possessed. She was always endeavoring, therefore, to enlarge it by finding fresh channels and means of activity, and consequently became even an initiator of fresh undertakings. Thus, the change from propaganda among the young, to one among the working men of the city, effected by the Circle of the Chaikovsti in the years 1871 and 1872, was in great part due to the initiative of Sophia Perovskaya. When this change was accomplished, she was among the first to urge that from the towns it should pass to the country, clearly seeing that in Russia if a party is to have a future it must put itself in communication with the mass of the rural population. Afterwards, when she belonged to the Terrorist organization, she made every effort to enlarge the activity of her party, which seemed to her too exclusive.

This perpetual craving, however, arose in her from the great reasoning powers with which she was endowed and not from romantic feeling, which generally springs from a too ardent imagination. Of such romantic feeling, which sometimes impels to great undertakings, but ordinarily causes life to be wasted in idle dreams, Sophia Perovskaya had not the slightest trace. She was too positive and clear-sighted to live upon chimeras. She was too energetic to remain idle. She took life as it is, endeavoring to do the utmost that could be done, at a given moment. Inertia to her was the greatest of torments.

For four years, however, she was compelled to endure it.

II.

On November 25, 1873, Perovskaya was arrested, together with some working men among whom she was carrying on the agitation in the Alexander Nevsky district. She was thrown into prison, but, in the absence of proofs against her, after a year’s detention was provisionally released on the bail of her father, and had to go into the Crimea, where her family possessed an estate. For three years Sophia remained there, without being able to do anything, as she was under strict surveillance, and without being able to escape, because she would have thereby compromised all those who had been provisionally released instead of waiting their trial “of the 193” in which almost all the members of the society of the Chaikovtsi were implicated as well as Sophia Perovskaya.

Here it may not be out of place to notice a special incident in connection with her first appearance in public, which affords an illustration of her character.

The accused in this trial not wishing to be mere playthings in the hands of the government, which fixed the sentences before the proceedings commenced, resolved to make a solemn demonstration. But of what nature this demonstration should be was not settled before the final day.

Sophia Perovskaya being out on bail, went to the trial without knowing the designs of her friends, who were in prison; and was purposely brought before the court first, as it was thought she would be taken unawares, and that the influence of her example might be turned to account. This hope, however, was completely frustrated. Sophia, seeing herself quite alone, declared, directly her first surprise was over, that she would take no part whatever in the trial, as she did not see those whose ideas she shared, and whose fate she wished to share.

This was precisely. what had been resolved upon at the same moment, in the cells of the prison. Sophia was acquitted, not released, however, as might have been expected, but consigned to the gendarmes, in accordance with a mere police order to intern her in one of the northern provinces. This is how all political offenders in Russia who are acquitted by the tribunals are treated.

Henceforth, however, no moral obligation any longer weighed upon her. She resolved, therefore, to escape, and profiting by the first occasion which offered, she did escape, without being aided by any one, without even apprising her friends. Before any one, indeed, had heard of it, she returned to St. Petersburg, smiling and cheerful, as if nothing had happened, and related the story of her flight, so simple, innocent, and almost charming, that, among the terrible adventures of her life, it is like a rhododendron blossoming among the wild precipices of the Swiss Alps.

In 1878 she again took an active part in the movement. But when, after an absence of four years, she returned to the field of battle, everything was changed there—men, tendencies, means.

The Terrorism had made its first appearance.

She supported this movement, as the only one to which owing to the conditions created by the Government, recourse could be had. It was, indeed, in this tremendous struggle that she displayed her eminent qualities in all their splendor.

She very soon acquired in the Terrorist organization the same influence and the same esteem she had had in the Circle to which she previously belonged.

She was of a voracious energy. Indeed, she could do alone the work of many. She was really indefatigable. She carried on the agitation among the young, and was one of the most successful in it; for, to the art of convincing, she united the much more difficult art of inspiring enthusiasm and the sentiment of the highest duty, because she was full of it herself. Directly the opportunity offered, she carried on the agitation among the working men, who loved her for her simplicity and earnestness, which always please the people; and she was one of the founders of the workingmen’s Terrorist Society, called Rabochaya Druzhina, to which Timothy Mikhailov and Ryssakov belonged. She was an organizer of the highest order. With her keen and penetrating mind, she could grasp the minutest details, upon which often depends the success or failure of the most important undertakings. She displayed great ability in the preparatory labors that require so much foresight and self-command, as a word let slip inopportunely may ruin everything. Not that it would be repeated to the police, for the secluded life led by the Nihilists renders such a thing almost impossible; but by those almost inevitable indiscretions, as, for instance, between husband and wife, or friend and friend, by which it sometimes happens that a secret, which has leaked out from the narrow circle of the organization through the thoughtlessness of some member, in a moment spreads all over the city, and is in every mouth. As for Sophia Perovskaya, she carried her reserve to such an extreme that she could live for months together with her most intimate personal friend without that friend’s knowing anything whatever of what she was doing.

From living so long in the revolutionary world, Perovskaya acquired a great capacity for divining in others the qualities which render them adapted for one kind of duty rather than another, and could control men as few can control them. Not that she employed subterfuges; she had no need of them. The authority she exercised was due to herself alone, to her firmness of character, to her supremely persuasive language, and still more, perhaps, to the moral elevation and boundless devotion which breathed forth from her whole being.

The force of her will was as powerful as that of her intellect. The terrible toil of perpetual conspiracy under the conditions existing in Russia; that toil which exhausts and consumes the most robust temperaments like an infernal fire; for the implacable god of the Revolution claims as a holocaust not merely the life and the blood of its followers—would that it were so—but the very marrow of their bones and brain, their very inmost soul; or otherwise rejects them, discards them, disdainfully, pitilessly; this terrible toil, I say, could not shake the will of Sophia Perovskaya.

For eleven years she remained in the ranks, sharing in immense losses and reverses, and yet ever impelled to fresh attacks. She knew how to preserve intact the sacred spark. She did not wrap herself up in the gloomy and mournful mantle of rigid “duty”. Notwithstanding her stoicism and apparent coldness, she remained, essentially, an inspired priestess; for under her cuirass of polished steel a woman’s heart was always beating. Women, it must be confessed, are much more richly endowed with this divine flame than men. This is why the almost religious fervor of the Russian Revolutionary movement must in great part be attributed to them; and while they take part in it, it will be invincible.

Sophia Perovskaya was not merely an organizer; she went to the front in person, and coveted the most dangerous post. It was that, perhaps, which gave her this irresistible fascination. When fixing upon any one her scrutinizing regard, which seemed to penetrate into the very depths of the mind, she said, with her earnest look, “Let us go”. Who could reply to her, “Not I”? She went willingly, “happy”, as she used to say.

She took part in almost all the Terrorist enterprises, commencing with the attempt to liberate Voynaralsky in 1878, and sometimes bore the heaviest burden of them, as in the Hartmann * attempt, in which, as the mistress of the house, she had to face dangers, all the greater because unforeseen, and in which, by her presence of mind and self-command, she several times succeeded in averting the imminent peril which hung over the entire undertaking.

As to her resolution and coolness in action, no words sufficiently strong could perhaps be found to express them. It will suffice to say that, in the Hartmann attempt, the six or eight men engaged in it, who certainly were not without importance, specially entrusted Sophia Perovskaya with the duty of firing the deposit of nitro-glycerine in the interior of the house, so as to blow into the air everything and everybody, in case the police should come to arrest them. It was she, also, who was entrusted with the very delicate duty of watching for the arrival of the Imperial train, in order to give the signal for the explosion at the exact moment, and as is well known, it was not her fault that the attempt failed.

I will not speak of the preparation for what took place on March 13, for it would be repeating what everybody knows. The Imperial Prosecutor, anxious to show how little power the Executive Committee possessed, said the best proof of this was that the direction of a matter of so much importance was entrusted to the feeble hands of a woman. The Committee evidently knew better, and Sophia Perovskaya clearly proved it.

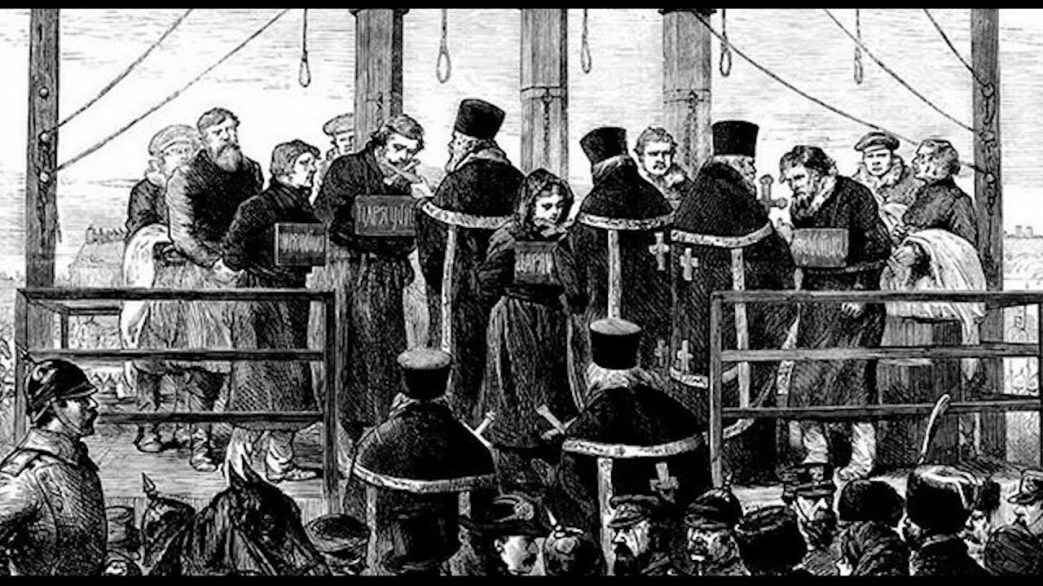

She was arrested a week after March 13, as she would not on any account quit the capital. She appeared before the court, tranquil and serious, without the slightest trace of parade or ostentation, endeavoring neither to justify herself nor to glorify herself; simple and modest as she had lived. Even her enemies were moved. In a very brief address she simply asked that she might not be separated, as a woman, from her companions, but might share their fate. This request was granted.

Six weary days the execution was postponed, although the legal term for appealing and petitioning is fixed at only three.

What was the cause of this incomprehensible delay? What was being done to the condemned all this time?

No one knows.

The most sinister rumors soon circulated throughout the capital. It was declared that the condemned, in accordance with the diabolically Jesuitical advice of Loris Melikov * were subjected to torture to extract revelations from them; not before but after the sentence, for then no one would hear their voices again.

Were these idle rumors, or indiscreet revelations?

No one knows.

Having no positive testimony we will not bring such an accusation, even against our enemies. There is one indisputable fact, however, which contributed to give greater credence to these persistent rumors; the voices of the condemned were never heard again by any one. The visits of relatives, which, by a pious custom, are allowed to all who are about to die, were obstinately forbidden, with what object, or for what reason, is not known. The Government was even not ashamed to have recourse to unworthy subterfuges in order to avert remonstrance. Sophia Регoуskaya’s mother, who adored her daughter, hastened from the Crimea at the first announcement of the arrest. She saw Sophia for the last time, on the day of the verdict. During the five other days, under one pretext or another, she was always sent away. At last she was told to come in the morning of April 15, and that then she would see her daughter.

She went; but at the moment when she approached the prison the door was thrown open, and she saw her daughter, in truth—but upon the fatal cart. It was the mournful procession of the condemned to the place of execution.

I will not narrate the horrible details of this execution. “I have been present at a dozen executions in the East,” says the correspondent of the Kölnische Zeitung, “but I have never seen such a butchery (Schinderei).”

All the condemned died like heroes.

“Kibalchich and Zheliabov were very calm, Timothy Mikhailov was pale, but firm, Ryssakov was liver-colored. Sophia Perovskaya displayed extraordinary moral strength. Her cheeks even preserved their rosy color, while her face, always serious, without the slightest trace of bravado, was full of true courage and endless abnegation. Her look was calm and peaceful; not the slightest sign of ostentation could be discerned in it.”

So speaks, not a Nihilist, not even a Radical, but the correspondent of the Kölnische Zeitungt (of April 16, 1881), who cannot be suspected of excessive sympathy with the Nihilists.

At a quarter past nine Sophia Perovskaya was a corpse.

The above had already gone to press, when I received, from her friends, the copy of a letter from Sophia Perovskaya to her mother, written only a few days before the trial. The translation which follows will not, I think, be unacceptable to my readers. I am far indeed, however, from flattering myself that I have preserved the warm breath of tenderness and affection, the indescribable charm, which render it so touching in the Russian language.

Being under no delusion as to the sentence and fate which awaited her, Sophia endeavored to gently prepare her mother for the terrible news, and to console her beforehand as far as possible.

“My dear, adored Mamma,—The thought of you oppresses and torments me always. My darling, I implore you to be calm, and not to grieve for me; for my fate does not afflict me in the least, and I shall meet it with complete tranquility, for I have long expected it, and known that sooner or later it must come. And I assure you, dear mamma, that my fate is not such a very mournful one. I have lived as my convictions dictated, and it would have been impossible for me to have acted otherwise. I await my fate, therefore, with a tranquil conscience, whatever it may be. The only thing which oppresses me is the thought of your grief, oh, my adored mother! It is that which rends my heart; and what would I not give to be able to alleviate it? My dear, dear mother, remember that you have still a large family, so many grown-up, and so many little ones, all of whom have need of you, have need of your great moral strength. The thought that I have been unable to raise myself to your moral height has always grieved me to the heart. Whenever, however, I felt myself wavering, it was always the thought of you which sustained me. I will not speak to you of my devotion to you; you know that from my infancy you were always the object of my deepest and fondest love. Anxiety for you was the greatest of my sufferings. I hope that you will be calm, that you will pardon me the grief I have caused you, and not blame me too much; your reproof is the only one that would grieve my heart.

“In fancy I kiss your hand again and again, and on my knees I implore you not to be angry with me.

“Remember me most affectionately to all my relatives.

“And I have a little commission for you, my dear mamma. Buy me some cuffs and collars; the collars rather narrow, and the cuffs with buttons, for studs are not allowed to be worn here. Before appearing at the trial, I must mend my dress a little, for it has become much worn here. Good-by till we meet again, my dear mother. Once more, I implore you not to grieve, and not to afflict yourself for me. My fate is not such a sad one after all, and you must not grieve about it.

“Your own Sophia.

“March 22 (April 3), 1881.”

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/soviet-russia-vol.-1-7-june-1919-december-1922/Soviet%20Russia%2C%20Vols.%206-7%2C%20January-December%201922.pdf