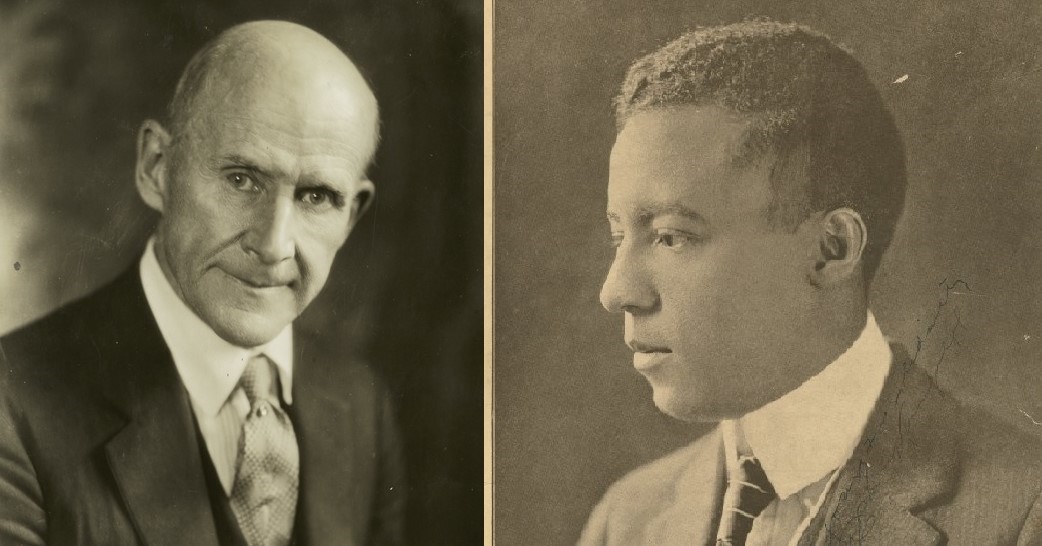

‘Letter to A. Philip Randolph’ by Eugene V. Debs from The Messenger. Vol. 5 No. 5. May, 1923.

MY DEAR COMRADES:

April 9, 1923.

During my absence from here while filling a series of speaking engagements a letter was received from you, as I am advised, and forwarded along with some other mail which duly reached me, but the letter from you seems to have gone astray in the mails. At least it did not come to me and I am unable to trace it, and this must be my apology for your not hearing from me. In your letter there was a request, as I am informed, for an article for THE MESSENGER, which I should have been glad to prepare and send if time had permitted the preparation of an article worthy of your columns. But at present, on account of many demands upon my time, there is little chance to do any writing, gladly as I would respond to your request for an article for THE MESSENGER. Although not yet entirely recovered, I have undertaken a rather strenuous speaking program, and in connection with this there are so many demands upon my time, and so many people to see at every point I visit, that there is barely time to meet the most pressing demands for attention.

I take pleasure in enclosing a brief contribution expressive of my sympathy and good will which you have always had in the splendid efforts you have been putting forth to awaken your race, and to set the feet of our Colored comrades and fellow workers in the path to emancipation.

All my active life I have been in especial sympathy with the Negro and with every intelligent effort put forth in his behalf. I know how he has been outraged in “free America” from the very hour he was stolen from his home, landed here like an animal, and sold into slavery from the auction block, and every time I meet a colored man face to face, even in prison, I blush with a sense of guilt that prompts me to apologize to him for the crime perpetrated upon his race by mine. Many years ago in traveling through the Southern States I urged and entreated labor unions to open their doors to the Negro and to admit him to fellowship upon equal terms with themselves, but in vain, and many an experience I had in that section to convince me of the deep-seated and implacable hatred and prejudice that prevailed against the Negro, and the impossibility of his securing justice in such a poisoned atmosphere and under such barbarous conditions. But more recently there has been some slight change for the better, due mainly to the pressure of economic conditions and to the growing conviction among Negroes that they themselves will have to take the initiative in whatever is undertaken to lift them out of their ignorance and slavery and out of the white man’s brutal domination.

Permit me to congratulate you upon the growing excellence of THE MESSENGER. You have a series of articles and a variety of matter in the current issue that is eminently to your credit and the credit of your race. You are kind enough to write of me in a very flattering way, and coming from no other source would such an estimate, all too generous, touch me more deeply or afford me greater satisfaction. You do me the honor to place me in nomination for president, and coming from my Negro comrades this is a recognition of special value to me, but I wish no nomination for any office and I aspire to no higher honor than to stand side by side with you in the daily struggle, fighting the battles of the workers, black and white and all other colors, for industrial freedom and a better day for all humanity.

You are doing a splendid work in the education of your race and in the quickening of the consciousness of their class interests, in common with the interests of all other workers, and I heartily wish you increasing success and the realization of your highest aims and your noblest aspirations.

Thanking you again and again for your kindness and devotion so often and so loyally made manifest, I am always

Your loving comrade,

EUGENE V. DEBS.

The Messenger was founded and published in New York City by A. Phillip Randolph and Chandler Owen in 1917 after they both joined the Socialist Party of America. The Messenger opposed World War I, conscription and supported the Bolshevik Revolution, though it remained loyal to the Socialist Party when the left split in 1919. It sought to promote a labor-orientated Black leadership, “New Crowd Negroes,” as explicitly opposed to the positions of both WEB DuBois and Booker T Washington at the time. Both Owen and Randolph were arrested under the Espionage Act in an attempt to disrupt The Messenger. Eventually, The Messenger became less political and more trade union focused. After the departure of and Owen, the focus again shifted to arts and culture. The Messenger ceased publishing in 1928. Its early issues contain invaluable articles on the early Black left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/messenger/v5n05-may-1923-Messenger-riaz-fix.pdf