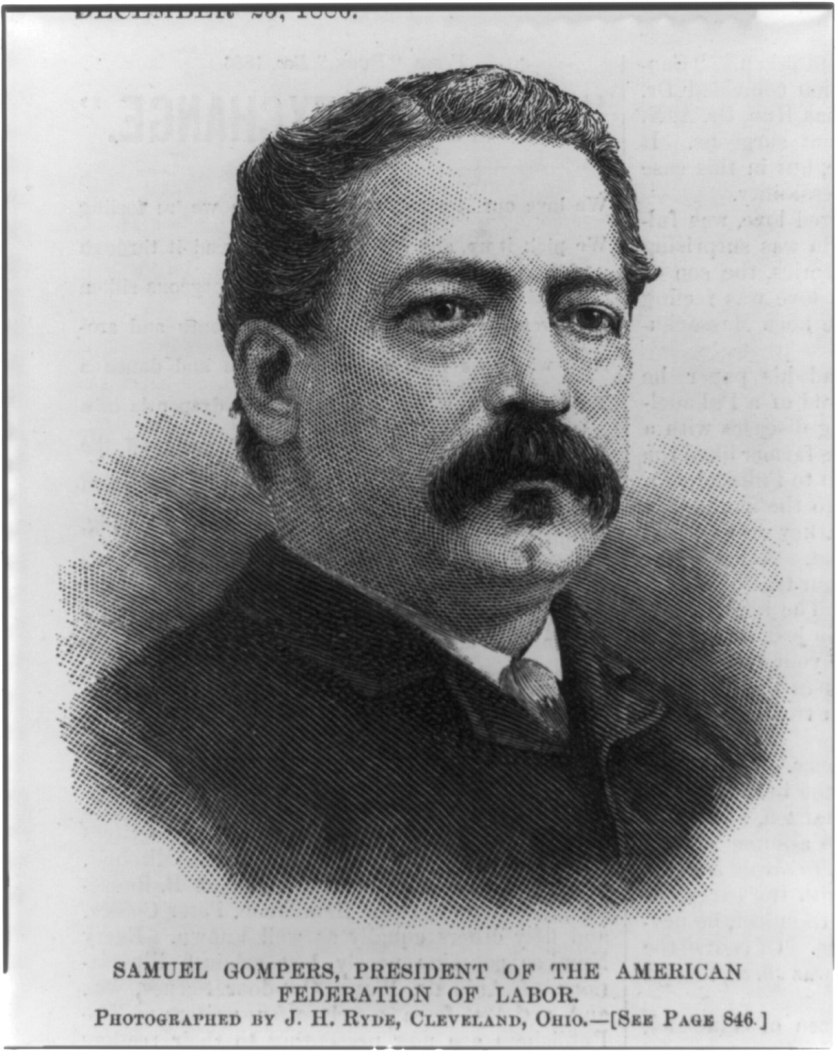

For two generations Samuel Gompers exercised immense power over the U.S. labor movement, shaping the American Federation of Labor in his image. In many ways, the U.S. labor movement has yet to move beyond ‘Gomperism,’ to all of our great detriment. In 1909 Gompers went to Europe on a ‘fact finding’ mission and addressed workers there. Karl Kautsky was not impressed and wrote this scathing report, giving as precise and accurate an account of Gomperism as any U.S. comrade in the process. First published in the August 13, 1909 edition of ‘Die Neue Zeit,’ and immediately translated by Henry Kuhn here for the S.L.P.’s Weekly People.

‘Samuel Gompers’ by Karl Kautsky from The Weekly People. Vol. 19 No. 23. September 4, 1909.

Gompers, the president of the great American Federation of Labor, has come to Europe in order to study, so he says, the labor conditions of Europe and to initiate closer relations between the American and the European trade unions.

In the one as well as in the other endeavor, he may count on being met half way by all proletarian organizations. The Social Democracy has always supported whosoever came to study labor conditions, even when he came from the enemy’s camp; the more so the president of an organization like the Federation of Labor. And so soon as we value closer relations of so powerful a proletarian organization–which also encompasses thousands of party comrades–with European organizations of the class struggle, we must, at every step that is to lead to this end, show to the plenipotentiary of this organization that degree of rapprochement which the organization itself deserves, without subjecting his person to specific criticism.

We know not whether and how Gompers has hitherto been active towards the consummation of the two tasks he has set himself. Certain it is that, besides, he is active in a yet different direction. He travels in Europe to have himself acclaimed at public meetings and to propagate that particular kind of trade union activity for which he stands. But as soon as he enters that field, he enters on ground upon which every one must be content to submit to public criticism. The duties of international solidarity by no means demand of us to agree, without critique, with every propagandist stranger just because he comes from abroad. It is just because it is often a case of persons, and conditions one does not know closely, that there is need of looking at them carefully before offering support. And applause means support. At the meeting, held by Gompers in Berlin on July 31st, to speak about the trade union movement, he, strange to say, prevented the comrades who were present from finding out with whom they really had to deal, by simply designating any question as to how he stood towards Social Democracy as “improper” and “personal”! This being so, Mr. Gompers must consent that others answer the question for him. I regret that my absence from Berlin, at that time, prevented me from doing this sooner.

At the meeting in the trade union hall (Gewerkschaftshaus), it had already been pointed out that Gompers is an enemy of the American Social Democracy. Legien, as against that, contended that Gompers is a true revolutionist who is striving to unite the proletarian masses. If he did this in a form other than our own, we had no right to judge him. That concerned only the American workers. In case Comrade Legien has received this explanation from Gompers, he has, indeed, been badly deceived, Nothing can be more erroneous than such an assertion.

Gompers is not only an opponent of the specific form that the Socialist Movement has taken in America, but is an opponent of the proletarian class struggle as such. To appreciate his views, one must know, not only what he tells his European friends, but also what he says to the American public.

Let us only hear what he declared on the day before his departure for Europe at a farewell banquet in New York. This banquet was in itself characteristic. Besides representatives of labor organizations there had come quite a number of representatives of capitalism and its glad-hand men (Handlanger), among them the District Attorney of New York, Before these, he explained that he was going to Europe to study, to see whether there the “so much praised methods were really the correct ones.”

But, he added, that he already knew that these methods were wrong. [At this point Kautsky quotes from the speech of Gompers, delivered at the banquet. He cites the president of the A. F. of L. as saying that the kind and the manner of European labor politics are thoroughly displeasing; that shortly after the convention of the Federation he (Gompers) had got in touch with sundry labor organizations and governments in European countries and had asked them to afford him an opportunity to orient himself on conditions in those countries at a meeting wherein all factions of labor organizations and representatives of the government would be present; that shortly he had received from Budapest, Hungary, two letters, one representing be workers, the other the government, and that both almost in the same words had declared that such a meeting could not take place because the relation be- tween labor organizations and the government were not such as to make possible joint deliberation or action; and that herein seemed to him to lie the kernel of the nut why the standard of life is so much better in America than in Europe: in America the representatives of labor and of the government could always come together to deliberate; that on the very evening of the banquet one could see the living proof thereof: none had been received by organized labor more heartily than the District Attorney of New York City, and that things must be so. Too often had the two parted without having agreed, but each time they learned to know each other better and why should they hot? Was there not for all the common fatherland, the common interests, the wish felt by all to make the people happier, freer and more joyful? He knew he would not see this abroad, but he could say that nothing could convince him that the readiness for conflict of the workers against the government, and contrariwise, the government against the workers could bring any good to either side. His message to his European brothers would be a message of love, of harmony, and of mutual trust to each other, “to us and to our compatriots.”]

Here we have Gompers the politician. He flows over with confidence in his capitalist compatriots; with the conviction that they all strive for the good of the people; that they have common interests with the proletarians. Political antagonisms are not the product of class antagonisms but the product of stupidity. Were Germany’s workers and bourgeois all as wise as Mr. Gompers, there would be no class struggle in Germany.

For all that, it cannot be assumed that this blissful confidence arises because in America the governments and capitalists are particularly friendly to Labor. There is scarcely a more unscrupulous and sordid capitalist class than that of America; and there is scarcely a country wherein the capitalist class dominates more completely the political power, wherein laws are made and executed and broken–if it is profitable–more shamelessly in favor of the capitalists and against the workers than in the United States. Notwithstanding all that, Gompers is full of confidence.

His harmony dope is not, however, like an occasional pretty turn of speech to catch bourgeois applause; it has become the essence of his political activity. Thanks to this he has managed to become first vice-president of the Civic Federation, a capitalist establishment of recent years, brought forth by the advent of the Social Democracy, and which has set itself the aim to bring together workers and bourgeois in a common effort. In truth and in fact it has become a militant organization against Socialism and the proletarian class struggle against which, because of the amplitude of funds at its disposal, it conducts an energetic propaganda. The Civic Federation, in point of fact, is getting to be, in the United States, ever more what the Imperial Union (Reichsverband) is in Germany. And it is the vice-president of this American Imperial Union who was presented, on July 31st, to the workingmen of Berlin as a man who is a true revolutionist and, therefore, as deserving of their warmest sympathy.

And the way he obtained this sympathy is also characteristic of Mr. Gompers. As we have seen, he had promised, in his farewell address, to preach to the workers of Europe the same evangel of harmony and confidence between Capital and Labor that he espouses in America. Stronger yet did his friends declare this. [Here Kautsky quotes Jacob Cantor as saying that it would be easy for Gompers in going to Europe practically as plenipotentiary, of the American workmen, to revolutionize the labor movement of the Old World according to his “sane” principles, and show them there what can be accomplished under “sane” and conservative leadership.]

But so much Gompers has already learned in Europe that he knows he would only make himself ridiculous with his gospel of harmony and confidence and he wisely keeps it to himself. And when Comrade Dittmer, by his questions, wanted to give him a chance to develop his “sane principles,” wherewith he can “with ease revolutionize the Labor Movement of the Old World” he does not seize this opportunity with avidity to make propaganda for his convictions, but feels bitterly wronged by this indiscreet ferreting into his private affairs. The double role of president of the Federation of Labor and vice-president of the Civic Federation Gompers plays only in America. In Europe he appears exclusively as the president of the Labor Federation. That of vice-president of the Imperial Union he forgot about on his trip across.

As a Socialist baiter Mr. Gompers acts only on a stage where he is sure of his claque. Caution is the better part of valor.

Why did the hide of the vice-president of the American Imperial Union itch so much that he must go just into the camp of the Social Democracy in order to get, specifically, their approbation?

Aye, he would not have done it, were it not that he needs this approbation very much.

Mr. Gompers is in a fair way of getting to the end of his rope in America. His “mis-successes” were of late too great. Of that, of course, he said nothing to his auditors in Berlin. These mis-successes also are only his “private affairs.”

He praised his “labor politics,” thanks to which the standard of living of the workers of America was higher than in Europe. This is ridiculous–humbug. The American workers have not attained a higher standard of living during recent decades, but have inherited it from their forefathers. It was, above all, a consequence of the presence of free land, of which everyone who wanted to acquire independence, could get as much as he needed. It is, primarily, due to this that the standard of living in general, as well as that of the wage workers in particular, has been, and is yet, far higher in America than in Europe.

But this superiority, on which Gompers prides himself so much, is rapidly vanishing.

This is being attested by the complete cessation of emigration from Germany to America. But a few decades ago, the German workingman improved considerably his condition when he emigrated to. the United States and, for that reason, many sought their fortune there. Today, the superiority of the American standard of living has become so minimized, that emigration no longer pays. The German workingman has, during the last decade, generally raised his standard of living. That of the Ameri- can workingman has RECEDED. If the purchasing power of his wages, according to the census of 1896, often quoted by me, still stood 4.2 per cent above the average of the decade 1890-1899, it was only 1.5 per cent. in 1907, and that 11% per cent. he has surely lost during the crisis.

Just in the decade of the domination of the American Labor Movement by Mr. Gompers has the upward movement of the American working class come to a standstill.

We know very well that this depends upon factors for which Gompers is not responsible. The giving out of the free land reserves, the influx of masses of workers with a low standard of living, the establishment of large industries in the southern states and, nor is this the least, the strong growth of capitalist organizations, have brought about this result.

But it proves, at any rate, that Gompers has not the least cause to boast about the superiority of American over European labor conditions and to present that superiority to the workers of Europe as the fruit of his policy of harmony and confidence.

Gompers has not created the degrading influences of capitalism which at present make themselves so strongly felt in America; but he has done his best to smoothen their path, because, through his policy of conciliation, he has condemned the proletariat to complete political impotence.

The proletariat can only then develop political power, when it is united in a separate political class organization. Gompers and his men have brought their entire influence to bear to make im- possible such an organization. Not a separate labor party shall the proletarians form, but they shall sell their votes to the highest bidder amongst capitalist candidates. Only they must not do it in the crude form of selling their votes for money. They were to give them to that one of the capitalist candidates who made the most promises.

A more ridiculous, also a more corrupting and, for the proletariat, politically demoralizing policy, is unthinkable. Thanks to that policy, there is not a democratic, industrial country where the workers are treated by their government and more particularly by the courts, with such disregard, as in America. From year to year, the freedom of action of the American proletariat, at one time so considerable, is being restricted. Never yet was this freedom of action 80 meagre as at present. The boycott has been made a crime. If the capitalists desire it, the strike too can, according to a decision of the U.S. Supreme Court, be made legally illusory. Practically, it has been that in consequence of the injunction. Labor legislation for the protection of life and limb is backward and does not make the slightest advance. If a legislative body does sometimes, and for demagogic reasons, pass an act in favor of the workers, it has no need to feel that the capitalists will be hurt thereby. The courts declare every encroachment upon the freedom of property as unconstitutional and are thus enabled to nullify every inconvenient law for the protection of the workers, which same they do perform conscientiously. Only recently did. the Supreme Court of Ohio declare invalid a law which prohibited night labor of children in factories. A decision of the highest court has declared as unconstitutional a Federal law, under which the railroads were made responsible for accidents to their employes, due to negligence of the roads. In the South of the United States, there prevails as yet the complete freedom in the exploitation of women and children, and the factories there repeat today, en masse, all the infamous and ghastly practices of the factory hells of Lancashire during the thirties and forties of the past century, which, at that time, were branded even by conservative politicians and which now, in our 20th century, pursue their murderous work, entirely unhampered, in the great republic that is so proud of its labor conditions. But not in the South alone do such conditions prevail. Only one example of many.

A bourgeois, philanthropic organ, “Charities” [now Survey], in New York, published, at the beginning of this year, an investigation of Pittsburg conditions, that is, of the “most prosperous” community in the world, the results of which were condensed in the following points (March 6, 1909):

“I. An altogether incredible amount of overwork by everybody, reaching its extreme in the twelve hour shift for seven days in the week in the steel mills and the railway switchyards.

“II. Low wages for the great majority of the laborers employed by the mills, not lower than other large cities, but low compared with the prices, so low as to be inadequate to the maintenance of a normal American standard of living; wages adjusted to the single man in the lodging house, not to the responsible head of a family.

“III. Still lower wages for women, who receive for example in one of the metal trades, in which the proportion of women is great enough to be menacing, one-half as much as unorganized men in the same shops and one-third as much as men in the union.”

And, finally, the report names, amongst the beauties of Pittsburg, typhus and an enormous number of accidents which, year in, year out, cost thousands of human lives.

And, on top of all that, the most nefarious judicial murders, whenever it is a case of getting inconvenient proletarians out of the way, such as Moyer and Haywood, who, it is true, had committed the crime of having less confidence in the government than Mr. Samuel Gompers.

All this is not unknown to German trade unions. The irony of fate wills it that only recently a German trade unionist paper held these things up to me. I had in my “Road to Power” pointed to the decline of American wages and had said: “At the same time, no working class enjoys such freedom as that of America; none is more practical politically, freer of all revolutionary ideology, which might restrain it from the small tasks of bettering its condition.” Thereto the “Grundstein” replied: “What sort of freedom have the American trade unions? They have free suffrage, free coalition and assembly, the freedom of demonstration and, besides, the ‘freedom’ of injunctions. The practice of the courts, corrupted by trust gold to beat down trade union action by means of injunctions, is known the world over…. And then the practical(?) politics of the American workers. They consist of the renunciation of political representation of their own; since when is that called practical polities? That, indeed, is not revolutionary, but is servile ideology” (“Grundstein,” June 5, 1909).

The practical politics of Mr. Gompers are, therefore, an ideology, not revolutionary to be sure, but a servile ideology. And thus writes not the wicked “Vorwaerts,” but a very “sane” trade union organ. Its intention is to use this as a trump card against me, but I agree fully with it. However, what becomes now of Legien’s “true revolutionist”?

Despite the poor political training they have received, the American workers themselves are beginning to open their eyes to Gompers’ servile ideology; they are beginning to get ripe for Socialism. Gompers, whom Legien praised so much because he unites the workers, does not shrink from splitting the workers in order to maintain his power. Thus he had expelled from the Federation of Labor, in 1907, the Brewery Workers’ Union, 40,000 strong, because they were honeycombed too much (for him) with Socialist elements.

But the like of that alone did not suffice to master the rising rebellion; he had to attain a great political success and, therefore, he determined to utilize at the presidential election of last year, the entire political power of the Federation for one mighty blow.

He set up a program of four points and, with it, turned to both of the two big capitalist parties, the Republicans, the party of the big capitalists, and the Democrats, the party of the little capitalists and of all sorts of social quackery, led by the charlatan Bryan. Without having been authorized, in any way, by his organization, he promised its support to that one of the two parties which would accept his four points.

These four demands were: a law for the “regulation” of court injunctions which were making any strike impossible; a law which was to declare, specifically, that trade unions are organizations that do not come under the pro- visions of the laws against trusts, or the laws against organizations “in restraint of trade”; furthermore, extension of the eight-hour work-day, decreed since 1868 for government shops, to private undertakings doing work for the government (by no means an eight hour standard workday for all workingmen); and a Federal employers’ liability law.

More modest one cannot be; not even was there a demand made for securing the right to boycott, which the law also forbids. These four demands prove how miserable has become the condition of American workers in spite of all political freedom. Indeed, had not the courts even dared to declare trade union organizations illegal, as for instance in Ohio, where the trade union of the glass workers was designated as a “trust,” and it was ordered to dissolve this trust!

But, notwithstanding his modesty, and in spite of the mighty power of two million votes, controlled by the Federation of Labor, Gompers had no luck. The Republicans could dare to turn him down contemptuously. Bryan was wiser and more polite; he expressed sympathy with Gompers’ demands without outspokenly endorsing them and that was sufficient for Gompers to pitch in for Bryan with fiery zeal, to commit the Federation to the candidatures of Bryan, to disregard all “neutrality” and to-antagonize the Socialist candidate, Debs, with all the means of mendacity and slander, as becomes a vice-president of the Imperial Union.

Election day came and, lo and behold, the “success” of this “positive effort” was a crushing defeat. The electoral aid of the Federation had failed to materialize; during the election it had dispersed, politically, instead of uniting its votes upon. Bryan.

It turned out that the gain for Bryan, as far as action of the leaders of the Federation of Labor was concerned, had been equal to zero; that the workingmen cared not for Gompers’ election slogan, and that the Federation of Labor does not represent the slightest political factor in an election, in spite of its two million members.

The workers can exercise political power only in a party of their own. In that alone does their action attain oneness and force. “Kite-tail politics” as the policy of supporting capitalist candidates is called on the other side; creates in the ranks of the workers political lassitude, indolence and confusion; their votes are frittered away, neutralize one another and cease to have an effect. So great and so notorious was the discomfiture of Gompersian tactics at last year’s presidential election that it seriously shook his position.

This would have become at once manifest, had he not, in the nick of time, had the luck to become a “martyr.”

He was not exclusively the vice-president of the Civic Federation, but also still a bit of president of the Federation of Labor and as such he had come in conflict with the courts, despite all harmony.

After the election, in December, 1908, the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia had sentenced him to one) year’s imprisonment, because in the “American Federationist,” published by the Federation, a boycott notice had appeared! Also a contribution to the practical successes of Gompersian “confidence.”

The next result of this sentence was that, in the ranks of the militant workers, all criticism against Gompers was silenced. Even the Socialists, but recently so sharply attacked by him, declared that they stand behind him in his conflict with the courts.

But this halo could not last, the less so since the courts remembered, in good time, how useful the Gompersian “confidence” is for the ruling class. The Court of Appeals announced, in March, that, although the boycott is illegal, the said notice was not. It acquitted Gompers. It is not likely that the highest court will upset this decision. Gompers will scarcely go to jail and become a martyr. What then? It becomes urgent to quickly gain new prestige, and thus Gompers suddenly bethought himself of his inter-

Gompers has not been acquitted. The case of the three A. F. of L. officers is pending on appeal, national duties, which had hitherto sat upon him rather lightly.

He speculated on the strength of the international sentiment of Europe’s proletarians and on their limited understanding of things American. If he left the vice-president of the Imperial Union in America, and came only as the president of the powerful labor federation, he would have to be met with general enthusiasm. This enthusiasm, meant for the class organization of the American proletariat, he could, on his return to America, counterfeit into a jubilating endorsement of his own policy. What is intended as moral support of the proletarian class struggle, he can exploit as moral support in the work of laming the class struggle. by means of his idea of the harmony of interests between Capital and Labor. What is to stimulate the struggle for emancipation, shall contribute to discredit America’s Social Democracy, in that Gompers points out that it stands isolated in the world; that the Social Democrats of all countries had acclaimed him and his policy, without a voice of protest, and had thereby repudiated the American Social Democracy.

In short, Gompers wants to soft-soap the workers of Europe in order to gain the prestige, which he needs to continue the soft-soaping of the workers of America.

Should Mr. Gompers again experience the need of presenting himself to the workingmen of Germany, the comrades will know where they are at.

I do not, as stated, advise that Gompers be treated impolitely. If he really wants to study, every opportunity should be given to him. If he wants to establish organic connections be tween American and European trade unions, then treat him as a representative of a friendly power, without concern as to his personality.

But if he wants’ to propagate himself and his method and would busy himself to “enlighten” us, then, though he should be quietly listened to, we should not shut the mouth of such comrades as would like to know more about the American Imperial Union and its vice-president.

If Mr. Gompers really wants to “revolutionize” the labor movement of the old world in accordance with his “sane principles,” he must do it over and above board.

The comrades, however, should at all times bear in mind, in regard to him. that every hand that is moved to applaud Gompers, is raised to deliver a blow in the face of our American brother party, which has not a more dangerous, nor more venomous foe than Samuel Gompers.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-slp/090904-weeklypeople-v19n23.pdf