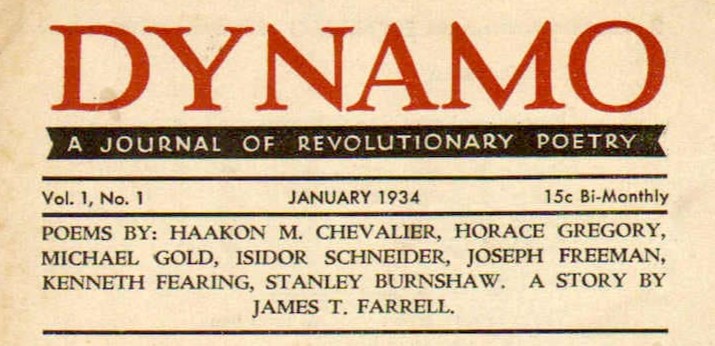

‘Dynamo, a Journal of Revolutionary Poetry’ by Alfred Hayes from The Daily Worker. Vol. 11 No. 14. January 16, 1934.

WE extend revolutionary greetings to “Dynamo,” a new journal of revolutionary verse, whose first issue has just appeared.

This little book is slender–24 pages; it will appear every two months; its voice is still uncertain, but, as Mike Gold would say, it’s a husky baby with a promising future.

There are probably hundreds of poets in America today, writing from mines, fields, cities, who are already giving form to the new theme in American life–the emergence of the proletariat as a class becoming conscious of its role as protagonist of the future classless society.

Unlettered workers (I have met workers who write “phonetic” poetry about their homes and shops because they can’t spell); young poets whose careers began with the crack of the Stock Market; and professional poets who are trying to break the patterns of despair and disillusion so fashionable in postwar literature–all are consciously engaged upon the task of creating a new poetry, a poetry unknown in the textbooks of school teachers or the looey untermeyer anthologies.

Its first accents can already be heard. In “Dynamo” we catch these new syllables, in many different voices, in the direct straightforward opening poem of Naakon Chevalier, “Worker, Find Your Poet,” in the subtler, more derivative rhythms of Horace Gregory’s “Night Watch From Chicago,” in the personal traditional lyrics of Joseph Freeman, in the simple factual “Workers’ Correspondence” of Michael Gold, in Isidore Schneider’s ironic “Comrade-Mister,” in the urbane sophisticate work of Kenneth Fearing, in the dramatic monologue, “New Youngfellow,” of Stanley Burnshaw.

There are many influences, different problems, different personal approaches, determined by the individual background, talent and conception of the individual poet. All of which is good. Revolutionary poetry should be varied, rich, multiform. To the critic of revolutionary poetry (there are as many or more than the poets) “Dynamo” will present an excellent source for examples to illustrate their theses. One can, for instance, choose the work of Horace Gregory, a poet of recognized standing, and use it to illustrate the failure or success of the problem of integrating “bourgeois” form with revolutionary content. Granville Hicks thinks it can’t be done. Or one can pick out Joseph Freeman’s six poems (why has he been hiding so long?) and praise or deny their highly subjective concern with the personal problems of a comrade in the movement. For this reviewer, all these are still open questions. Having seen how Louis Aragon (Red Front) has achieved a dynamic revolutionary poetry with forms created while he was a Surrealist, i.e., bourgeois poet, I am inclined to doubt Hicks’ answer. And having been moved by these “personal,” “subjective” lyrics of Joseph Freeman, I have wished more of our revolutionary poets turned to an honest expression of their “secret” selves. This reviewer believes, with one of the editors of “Dynamo,” that Joseph Freeman has succeeded in widening the scope of revolutionary expression in poetry. Knowing also how much workers enjoy good revolutionary poetry, I hope that they will lend their support to this little magazine of verse and not permit it to die one of these obscure financial deaths that so often overtakes our magazines.

“Dynamo” also publishes an unusual short story by James T. Farrell, a young proletarian writer, author of the novels “Gashouse McGinty,” and “Young Lonigan.”

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924. National and City (New York and environs) editions exist.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1934/v11-n014-jan-16-1934-DW-LOC.pdf