The full text of Cecilia Bobrovskaya’s 1932 biography of leading Bolshevik and central figure of early Soviet Russia Yakov Sverdlov, who died of disease on March 16, 1919. Along with a work written in 1939 by his second wife, this short pamphlet remains one of the most substantial biographies of Sverdlov in English, something that should change.

‘The First President of the Republic of Labour: A Short Biographical Sketch of the Life and Work of Yakov M. Sverdlov’ by Cecilia Bobrovskaya. Workers Library Publishers, New York, 1932.

PREFACE

“There are some people, leaders of the proletariat, about whom the press makes no fuss, perhaps because they do not like to make a fuss about themselves, but who are, nevertheless, the life blood and real leaders of the revolutionary movement. Y.M. Sverdlov was one of these.” J. STALIN, Proletarian Revolution, Vol. 11 (34), 1924.

FIFTEEN years have passed since those epoch-making days when the proletariat of former tsarist Russia began with its toil- hardened hands, the construction of the first Soviet republic in the world. Since then the eyes of the workers of all countries have been firmly fixed upon this first proletarian state; yet few people outside the Soviet Union know of the man who became the first president of that first republic of labour.

Proletarians in capitalist countries still know very little of the life and work of Yakov Mikhailovich Sverdlov who, as Lenin said: came to the post of first-man in the first Socialist Republic by the path of illegal political circles, underground revolutionary work, and an illegal party.” (V.I. Lenin, Speech in Memory of Sverdlov,” Collected Works. Russian edition. Vol. XXIV, p. 81.)

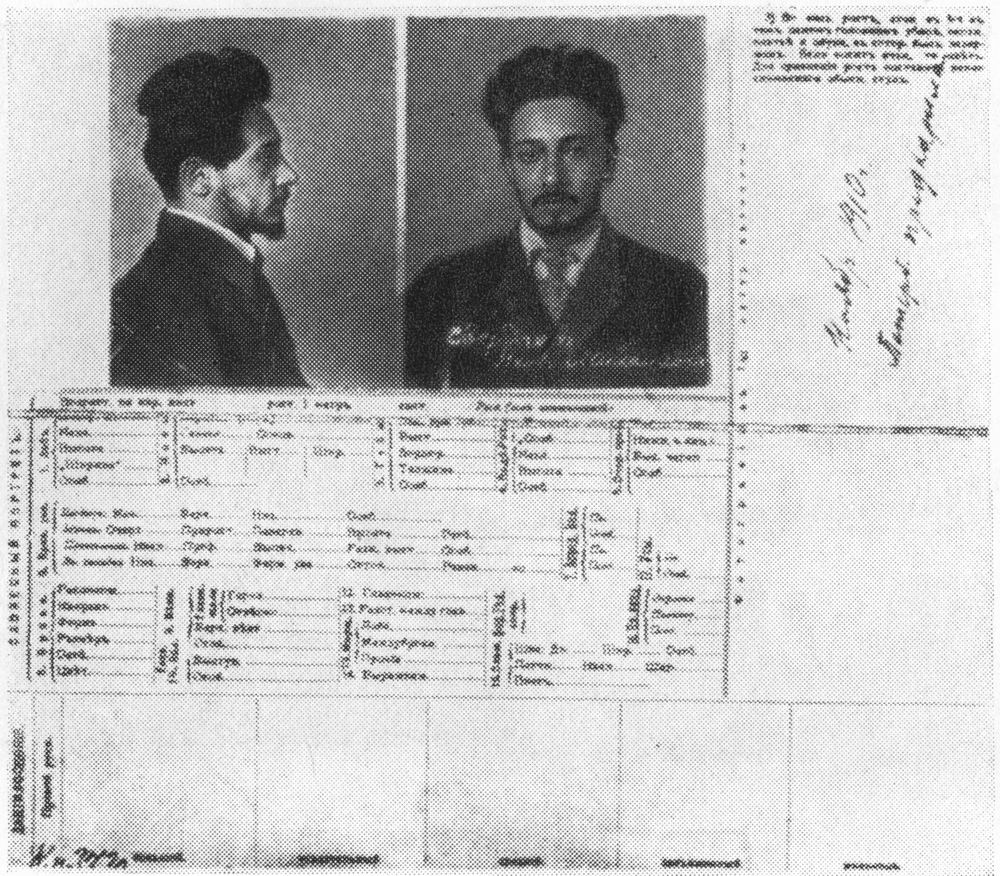

In this book we are using all the available material in Russian, both the statements of people who knew Y.M. Sverdlov personally at various periods of his revolutionary work, and the heritage left by our enemies, documents of the former tsarist police department, in which Sverdlov figures as early as 1902 as a dangerous revolutionary, despite his extreme youth (he was only seventeen at the time). On the basis of these materials we are attempting a short survey of Sverdlov’s difficult yet glorious life; we shall try to show his untiring revolutionary energy, the tremendous scope of his initiative and his brilliant talent as an organiser of the masses.

I. CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH

NIZHNI-NOVGOROD, where Yakov Sverdlov was born in May, 1885, stands on the banks of the broad river Volga, “Mother Volga,” the theme of many an old Russian song, of poems by Nekrasov, of famous Russian paintings such as Repin’s “Volga Barge Haulers.” Maxim Gorky too found inspiration for some of his earlier work on the Volga banks, and his book Mother, which later became universally known, was written in Sverdlov’s native town, Nizhni-Novgorod, with the revolutionary atmosphere preceding 1905 as a background.

Yakov was the third child in the family and although his father, a Jewish artisan engraver, did not earn very much, the Sverdlov family was never in acute want, and Yakov’s childhood under his mother’s affectionate care was tranquil enough.

From his earliest childhood Yakov showed, as one of his biographers (Gaysinsky) says, “unusual vivacity, a tendency towards the wildest pranks and, at the same time, an extraordinary shrewdness and keenness of mind. Even in his childhood he distinguished himself among his comrades by the most daring actions. In his pranks he showed the fearlessness so characteristic of the mature Sverdlov–the revolutionary. At the same time he displayed a staunchness and patience unusual for his age.”

As a child, he showed such an eagerness to learn, such a thirst for knowledge that when he was ten years old, his father, in spite of his limited means, placed him in the Nizhni-Novgorod high school. Needless to say, the state high school of tsarist times with its stifling atmosphere could not satisfy the boy’s searching mind; his home background at the same time was more favourable to his development.

The Sverdlov family sympathised with the revolutionaries who often came to Nizhni-Novgorod from the capital whence they had been expelled. In the Sverdlov flat on the Pokrovka one could meet old revolutionaries and young Marxists, conceal illegal revolutionary literature, make a business appointment with an illegal Party worker, and so forth.

Such was the background of Sverdlov’s youth. It was at home and in the books which he read so extensively that he found answers to the poignant questions which the state high school could not and did not answer, so that after finishing four classes, Yakov decided to leave high school, a decision not opposed by his father since his impoverished financial position no longer enabled him to keep his son at school. Thus Yakov was obliged, at the age of fifteen, to earn his own living, and he became an apprentice in a chemist’s shop.

It was at this time that Sverdlov experienced his first personal grief–the death of his mother, with whom he was in very friendly relations. After that the whole atmosphere of his home changed for the worse. The advent of a stepmother only served to hasten Sverdlov’s removal to the chemist’s shop where he now both worked and lived. He used his own home-his father’s workshop–more for the needs of the revolutionary organisation in which he began to take an active part in spite of his extreme youth.

The proximity of Sormovo, a big proletarian centre which even at that time, in 1900-1, had ten thousand skilled metal workers employed in its plants, was an added factor aiding the development of an intense political life in Nizhni-Novgorod. In other proletarian centres in Russia too, a rapid growth of political activity was evident. The workers’ movement had begun to acquire a mass character.

Lenin, in 1901, wrote concerning the ruthless suppression of a workers’ revolt at the Obukhov works in Petersburg, that:

“Apparently, we are now passing through a period in which our labour movement will once again lead precipitously to acute conflicts, which terrify the government and the propertied classes, and rejoice and encourage the socialists. Yes, we are rejoiced and encouraged by these conflicts, notwithstanding the numerous victims that fall by the hand of the military, because the working class is proving by its resistance that it is not reconciled to its position, refusing to remain in slavery or to suffer violence and tyranny in silence. Even in the most peaceful times, the present system inevitably imposes endless sacrifices on the working class.

“Thousands and tens of thousands of men and women, toiling all their lives to create wealth for others, perish from starvation and constant underfeeding, prematurely die from diseases caused by the horrible conditions under which they work, and the wretched conditions in which they live and overwork.

“He who prefers death in the open struggle against those who defend and protect this horrible system, rather than the lingering death of a crushed, broken-down and submissive wretch, deserves the title of hero a hundred-fold.” (V.I. Lenin, “Another Massacre,” The Iskra Period. Vol. IV, Book I, p. 117. International Publishers, N.Y.)

The first committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in Nizhni-Novgorod was formed in the autumn of 1901. Under its guidance the seventeen-year-old Yakov Sverdlov developed great revolutionary activity in propaganda, agitation and in connection with the organisation of a secret printing shop for Party literature.

Barely a year later we find in the report of the governor of Nizhni-Novgorod, dated April 25, 1902, a bitter complaint that all is not well in the province assigned to him, that the persons under surveillance in this town and “other political persons” took advantage of the sudden death of Rurikov, a student who had been under surveillance, “to attempt to organise an administrative disturbance.” It had been noticed that the wreathes placed on Rurikov’s grave bore the following inscriptions on their ribbons: “You did not spare your honest efforts in the struggle; we shall not forget your death, comrade!” “It is vengeance not tears that is needed!” etc. These ribbons afterwards disappeared. Besides wreaths and ribbons, two speeches carrying dangerous messages were made and all those present sang, to the tune of the Marseillaise, a song beginning with the words: “Arise ye Russian people, arise, our starving brothers. Forward, forward!” etc.

On the way back from the cemetery “evil-disposed suspects even decided to organise a demonstration march through the town. But the end, so usual in Russia at that time and so familiar to the proletarians of capitalist countries nowadays, quickly arrived. “Thanks to the energetic action of the police detachment which was at hand, the crowd was surrounded and dispersed in the shortest time and complete order was restored; the demonstrations of the crowd were checked at the entrance to Vsekhsvyatsky Lane, adjacent to the cemetery.” (From the file of the police department.)

Yakov Sverdlov was among those arrested and prosecuted for infringement of the rules decreed by this governor of the town of Nizhni-Novgorod. But the authorities could not impose upon him the governor’s order for two weeks’ confinement to prison, for Yakov Sverdlov had disappeared.

From the proceedings following the above report, however, it is clear that Sverdlov, who had good reasons to avoid the police of Nizhni-Novgorod after Rurikov’s funeral, did not, in the end, escape the punishment which his excellency, the governor, had meted out to him and that he had to spend two weeks in prison after all.

From that time on, that is, from the summer of 1902, the troublesome Sverdlov was watched unceasingly by the police. This “Malish” (“Young boy,” “kid” the police had given him this nickname) however, did not lose courage; he dexterously avoided the eye of the authorities and continued his energetic underground work in connection with the formation and reinforcement of the local Party organisation. Since objective conditions were favourable, the workers’ movement of 1902 gathered force and culminated in the historic strike of the workers at Rostov-on-Don. This in turn gave considerable momentum to our Party organisation. At that time too, numbers of the Iskra containing Lenin’s instructions were arriving regularly from abroad.

At the initiative of the Nizhni-Novgorod Committee, the Sormovo Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party was formed in 1902. It held a demonstration on the first of May in which two thousand workers took part under the slogan: “Down with Autocracy!” The active workers of this organisation were arrested after the demonstration and young Sverdlov was sent there from Nizhni-Novgorod to reinforce the organisation.

Another of his biographers, N. Nelidov, writes about this period of Comrade Sverdlov’s work, on the basis of data regarding the history of the Nizhni-Novgorod Party organisation: “The arrest of leaders of the organisation forced the Nizhni-Novgorod Committee to give Sormovo their most serious attention and the months of May and June were a period of strenuous organisational work among the workers of Sormovo. It was this difficult work, involving tremendous strain, that Sverdlov came to do.”

In spite of his youth he took a most active part in the restoration and organisation of the ranks of the Sormovo workers, temporarily disrupted. Yakov possessed an immeasurable store of energy, unusual sincerity, belief in and devotion to the cause, and the ability to approach the working masses; he was therefore absolutely invaluable for the work.

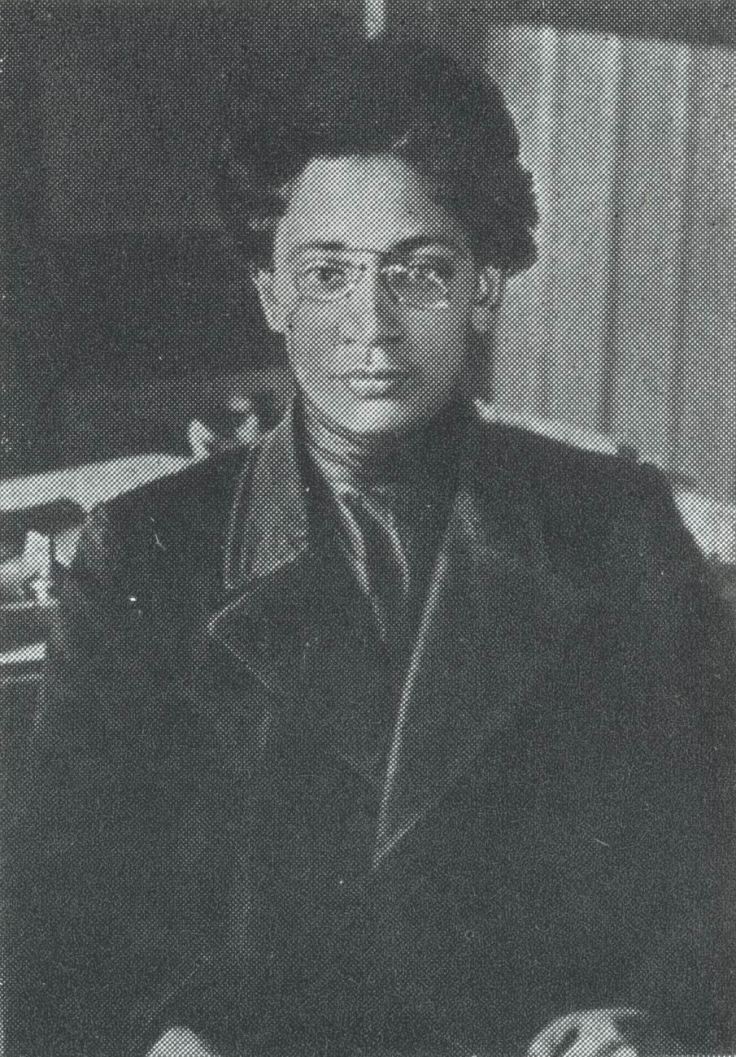

With his direct participation the Sormovo organisation developed mass agitation among the workers to a high degree. A month and a half later, Party activity was restored to its normal condition. A series of strikes took place. From July on, meetings of Sormovo workers occurred almost daily. And at these July meetings it was, that Yakov’s extraordinary qualities as an orator came to light. The seventeen-year-old agitator, short, thin, hair black as a raven, drew the working masses by the sincerity and conviction in his speeches. He united these workers in a singleness of purpose, he called upon them to struggle mercilessly against tyranny and violence. When news came to the Nizhni-Novgorod and Sormovo organisations, in 1903, that during its second congress the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party had split into Bolshevik and Menshevik factions, Sverdlov unhesitatingly and unwaveringly adopted Lenin’s position, sided firmly with the Bolsheviks and carried on a determined struggle with the Menshevist and conciliatory tendencies which arose in the Nizhni-Novgorod and Sormovo Party organisations. young Bolshevik Sverdlov was so active, the workers became so accustomed to hear his powerful voice at workers’ meetings that his youth was quite forgotten, and Yakov Sverdlov himself, more than anyone else, was deeply conscious of his responsibility for the work entrusted to him by the Party.

Sverdlov’s revolutionary activity was temporarily halted by the Tsar’s gendarmes who arrested him again at the end of 1903 for “belonging to the criminal society formed in Nizhni- Novgorod and also for having in his possession and spreading anti-government literature.”

We cannot discover precisely how long Sverdlov was kept in prison this time, since the exact date of his arrest is unknown, but file No. 2754 (1904) of the police department contains a document relating to “Myeschanin” (Literally, urban dweller under the tsarist regime the population was divided up into “estates” or “orders” such as nobles, merchants, peasants or urban dwellers, i.e., Myeschanin, etc.) Sverdlov who is under the open surveillance of the police of Nizhni-Novgorod!” This document states that Yakov Sverdlov, aged 19, is to be subjected to open police surveillance for two years, from February 11, 1904, in accordance with his majesty’s orders.

So by his majesty’s orders, Sverdlov was to be restricted in his movements to the town of Nizhni-Novgorod until February, 1906, but he would not stay in Nizhni-Novgorod; revolutionary energy was surging strongly in him, and his hands would have been tied in that town by the constant surveillance of the police. In order to develop his revolutionary powers freely, he left Nizhni-Novgorod and began his “underground” existence.

II. ON ILLEGAL WORK

In order to characterise the work and frame of mind of the nineteen-year-old Sverdlov at a moment crucial for every Party member-the period which saw the start of his underground life, we may cite the archives of the police department which have preserved a splendid illustration–a letter written by Sverdlov himself. This letter which was intercepted by the gendarmes was dated November 22, 1904, and addressed abroad, to Friedberg (Hessen), to a comrade who acted as connecting link between him and the Party centre. So characteristic is this document that we take the liberty of quoting the greater part of it.

“As you probably know, I spent one day in Moscow and left with the evening train for my final destination, Yaroslav. But I could stay there only three days, after which I went to Kostroma where I am at present. I took up my abode here as a “professional revolutionary” in accordance with the instructions of the Northern Committee which includes Kostroma. There is a lot of work to be done here and hardly anybody to do it–only three or four people except myself, of whom only one can be taken into account. I feel cheerful enough; true, sometimes I long for Nizhnis Novgorod, but on the whole I am glad I left, since I could not spread my wings there (and I think I’ve got wings); I learned to work there and I have come here trained, here where there is ample field for making use of my powers. There are quite a number of spies here too at present (they were introduced here in great numbers after the big disturbances of 1903), but they are not very clever, as I have already had occasion to remark.”

“I could not spread my wings there and I think I’ve got wings,” says young Sverdlov modestly, not knowing that thirteen years later, he was to soar on those wings to the highest peak of revolutionary achievement, that those wings would carry him to” the post of first-man in the first Socialist republic,” to the post of first organiser of the wide proletarian masses. “There is a lot of work to be done here-hardly anybody to do it. Only three or four people except myself, of whom only one can be taken into account.” In order to grasp the full meaning of these words we must know the circumstances of revolutionary work obtaining in the northern weaving district during that period.

This enormous textile centre, since the split in the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party, had supported Bolshevism, had supported Lenin. But at the same time, the tremendous discrepancy between the scope of the labour movement and the scarcity of skilled and experienced members of the Party who could help this movement assume the necessary organised forms, was felt in the Northern area more than anywhere else.

Sverdlov was a born bolshevik organiser and for that reason he was able to use his powers to the fullest extent here; that is why he wrote: “I learned to work there and I have come here trained, here, where there is ample field for making use of my powers.”

Having intercepted and deciphered Sverdlov’s letter, the police department became frightened. On December 18, 1904, a letter was sent to the chief of gendarmes in Kostroma under No. 14806 with instructions to “find out through secret channels the identity and actions” of a certain political suspect whose name or surname begins with the letter ‘Y’ and who arrived recently in Kostroma, evidently from Nizhni-Novgorod, with secret instructions from the Northern Committee of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party; also to find out, in the same way, the connections of the said revolutionary worker and to report the results.”

But Sverdlov had good reason to smile at the gendarmes of Kostroma in his letter: “there are quite a number of spies here at present, but they are not very clever, as I have already had occasion to remark.”

The naiveté of these gendarmes was truly astounding. On January 12, 1905, they reported that they had searched in vain for the suspect whose name or surname began with a ‘Y.’ On February 8, 1905, they reported that a certain Yakov Sverdlov had come to Kostroma from Nizhni-Novgorod, never for a moment suspecting that the two, the mysterious ‘Y’ and the new arrival from Nizhni-Novgorod, Yakov Sverdlov, might be connected. They were, of course, properly reprimanded afterwards by the police department for their dull-wittedness.

However, in spite of the stupidity of the spies whom Sverdlov ridiculed in his letter, he was not able to work long in Kostroma. Yet two to three months was considered a fair period at that time for an illegal Party member to work in one town. In such a length of time a clever and skillful Party member could do quite a bit.

Sometimes in a one-month period of Party work in a town or even in a whole region, a professional Party worker would succeed in righting the local organisation, in guiding the local workers from his experience, in supplying them with instructions, literature, connections with the bolshevik centre abroad, etc.

Such was the case with Sverdlov during the short period of his work in the Northern committee.

In an article entitled First Lessons, written in February, 1905, V.I. Lenin, in reckoning up some of the results of the years. directly preceding the 1905 revolution, says: “1901 is the year when the worker came to the students’ assistance. Demonstration movements arose, the proletariat carried its slogan “down with autocracy” into the street.

“After 1902, after the strike at Rostov, the political movement of the proletariat no longer joins with the students’ movement–but grows up itself immediately out of the strike.

“The proletariat as a class, for the first time, opposed itself to the other classes and the Tsar’s government.

“In 1903, strikes merged with political demonstrations on an even wider basis. Strikes spread over whole districts; over a hundred thousand workers participated in them. Mass political meetings occurred in various towns at the same time as strikes, there was a feeling that we were on the ‘eve of barricades,’ but the eve was prolonged, as if to accustom us to the fact that powerful classes sometimes store up their forces for months and years, as if to test the incredulous intellectuals.”

The eve of the barricades found the young Sverdlov a fully developed bolshevik organiser, agitator and propagandist. He had developed, grown as it were, together with his revolutionary Party, been forged in the fire of class battles, and he did not in the least resemble an incredulous intellectual although he belonged by birth to the petty-bourgeois class. By that time Yakov Sverdlov already possessed the endurance of a real revolutionary. He knew how to wait notwithstanding the fact that “the eve of the barricades was somewhat prolonged.”

III. PERIOD OF THE FIRST RUSSIAN REVOLUTION, 1905-1907

LENIN writes of 1905 that “in no capitalist country in the world-not even in advanced countries like England, the United States of America, or Germany, has such a tremendous strike movement been witnessed as that which occurred in Russia in 1905…It shows that in a revolutionary epoch-I say this without exaggeration on the basis of the most accurate data of Russian history-the proletariat can develop fighting energy a hundred times greater than in normal, peaceful times.

“It shows that up to 1905, humanity did not yet know what a great, what a tremendous exertion of effort the proletariat is capable of in a fight for really great aims, and when it fights in a real revolutionary manner!

“The history of the Russian Revolution shows that it is the vanguard, the chosen elements of the wage-workers who fought with the greatest tenacity and the greatest self-sacrifice. The larger the enterprises involved, the more stubborn the strikes were and the more often they repeated themselves during that year.”

In Kazan (now the capital of the Tartar Republic) where Sverdlov went from Kostroma in February, 1905, to continue his revolutionary work, the largest plant was the Alafuzov, with “select elements of hired workers” numbering four thousand. Sverdlov centred a great deal of attention upon this plant, as well as on many other major and minor enterprises. The shooting of the peaceful workers’ demonstration in Petersburg while on its way to the Palace Square, on January 9, 1905, to beg for the favour of Tsar Nicholas, had aroused great indignation among the working masses. Sverdlov explained to these workers of Kazan, who were angered and aroused by the Petersburg events, the necessity for concretely formulating their political as well as their economic demands. At mass meetings Sverdlov’s resounding voice gave out the bolshevik slogans to which the workers listened eagerly and which the masses took up.

Sverdlov’s stay in Kazan in the winter of 1905 was the more fortunate in that the social-democratic organisation which existed there at that time was a centrist one, adhering neither to the Bolsheviks nor to the Mensheviks. It was Sverdlov’s difficult task therefore to introduce bolshevik concreteness from an ideological as well as an organisational point of view.

Sverdlov became a member of the Kazan Party committee, its responsible organiser and propagandist, and he succeeded in doing some important revolutionary work in a short time. He inspired the working masses, the soldiers of the local garrison and the students, aroused them to greater efforts to bolshevise the whole Kazan Party organisation.

But Sverdlov’s work in those months was not limited to Kazan. He went, in accordance with instructions from the Central Committee of the Party, to Nizhni-Novgorod, Sormovo, Samara, Saratov, and in July, 1905, he was already in the Urals, as witnessed by a letter from the gendarmes’ office of Nizhni- Novgorod, No. 1058, of July 23, 1905, which says that Yakov Sverdlov, known to the police department under the nickname “Malish,” was seen in Perm by an agent of this office who happened to be there at the time and who informed the local secret police.”

In the Urals–one of the richest mining centres, among scores of thousands of miners who worked under the worst possible conditions, there was great scope for Sverdlov’s creative initiative. There were tremendous possibilities here of utilising his talent for organising the masses.

We read about this period of Sverdlov’s work in the documents of the Urals’ bolshevik organisation, in an article by Bykov.

“The Revolution of 1905 made it possible to develop agitation to the greatest degree in the districts near Yekaterinburg (now Sverdlovsk) and in other towns in the Urals. The short period of legal existence was used to reinforce the organisations, to establish stable connections with plants and form fighting detachments for defence against the Black Hundreds.

“In all this work Comrade Andrew (Sverdlov’s Party name) merits the greatest praise, for he succeeded in a short time in unifying several organisations, in organising the proper technique and in raising bolshevik propaganda and agitation to great heights.”

In the meantime, the revolutionary movement throughout the enormous country was developing with lightning speed, the frightened Tsar was forced to “grant the people a manifesto”–a pitiful mockery of constitutional guarantees.

In No. 25 of the bolshevik newspaper Proletary of November 3, 1905, V.I. Lenin wrote: “The denouement approaches. The new political situation is taking shape with the extraordinary speed peculiar to revolutionary epochs only. The government began to make concessions in words and simultaneously commenced to prepare in fact for an attack. The most savage and horrible acts of violence followed upon the promise of a constitution, as if to show the people still more clearly the whole significance of real autocratic power.”

A little later in November, when the Soviets of Workers’ Deputies had already been formed, Lenin described the situation thus:

“The state in which Russia finds herself at present is often described by the word ‘anarchy.’ This incorrect and wrong definition in reality expresses the fact that there is no established order in the country. The new, free Russia is waging a war all along the line against the old Russia of serfdom and autocracy…

“The old order is vanquished, but it is not completely destroyed yet and the new, free order exists unrecognised, partly hidden, very often persecuted by the hirelings of the autocratic regime.” (V.I. Lenin, “In the Balance,” Collected Works. Russian edition. Vol. VIII, p. 398.)

What part did Sverdlov take at that time in the war between “the new free Russia and the old Russia of serfdom and autocracy”? From the Urals he went to Nizhni-Novgorod and Sormovo where he spoke before the masses, whose revolutionary enthusiasm reached the highest pitch in the three-day fight on the barricades, December 12-15, 1905. Besides this he visited Moscow and spoke at crowded meetings in the Aquarium Theatre in the days directly preceding the revolt. From Moscow Sverdlov returned to the Urals where he found that the heroic attempt at armed fighting on the part of the workers of Perm and Motovilikha of December 9-13, 1905, had been suppressed. After the suppression of the Moscow revolt, a wave of unprecedented repressions passed over the country, the Tsar’s punitive expeditions were responsible for the bloodshed of the best sons of the revolution.

The Urals workers also paid dearly for their revolutionary daring, but no despondency and depression seized those active Party workers, including Sverdlov who had escaped the slaughter. Very active work was begun under Sverdlov’s direction to restore the Party organisation under the new and much more difficult conditions.

“It was necessary first of all, to restore the disrupted organisations, connections, technique, new workers had to be trained to replace those who were arrested, exiled or in hiding, account had to be taken of existing forces and underground work to be reinforced.

“All this complicated and varied work rested almost entirely on the shoulders of the tireless Mikhalych (Sverdlov’s Party name at the time), who was at the head of the Perm bolshevik organisations,” says Sverdlov’s biographer, Nelidov.

B. Ivanov gives the following particulars from personal reminiscences of his joint work with Sverdlov in the Urals in 1906:

“Sverdlov lived in the Urals on ten or twelve rubles a month. We did not know when he rested. Short and slight, with a shock of thick, raven black hair, wearing coarse boots, ‘Mikhalych’ went from meeting to meeting and wherever he appeared he imbued everyone with courage and assurance by his sonorous voice so out of keeping with his height.

“Thanks to his untiring energy and organisational ability he succeeded in uniting around the Urals bolshevik bureau, the biggest Party organisations of Perm, Yekaterinburg and Ufa. Under the firm and skillful hand of Mikhalych, the recently routed and dispersed organisation was fully restored, acquired strength, compactness and stability; provincial Party committees were formed, the Urals included a multitude of factory organisations of the Party.” (B. Ivanov, Symposium of the Perm Organisation on the History of the Party, 1923, p. 22.)

At meetings organised by Mensheviks, Socialist-Revolutionaries and Anarchists, the workers invariably elected Sverdlov chairman. “We want Comrade Andrew!” shouted the crowd. The people who had arranged the meeting, embarrassed by this demand, would begin complaining that Sverdlov was their ideological opponent and propose their own candidates for chairman, but the crowd went on shouting: “Andrew, Andrew!” Andrew was searched for, brought to the meeting and his speech flowed smoothly and convincingly out to the crowd; they would then refuse to hear any speeches from the

opponents of bolshevism and would adopt bolshevik resolutions. In this way Sverdlov broke up many Menshevik, Socialist-Revolutionary and Anarchist meetings.

Although the police dogged his footsteps, Sverdlov succeeded in remaining at liberty for quite a long time by means of various disguises and other tricks. But the gendarmerie, who were becoming more and more active, succeeded in introducing agent- provocateurs into the organisation and one of them, a man named Vatinev, gave Sverdlov away by stating that Sverdlov had appointed him to look after the store of arms.

I. Gluchin in his memoirs says that Sverdlov smilingly told his comrades the story of his arrest as follows: “I was accompanying a woman who was on underground work to the Perm station. We walked along Obkinskaya Street engaged in conversation. Suddenly I came face to face with a police officer of some district of Yekaterinsburg. The officer stopped and looked me in the eye for several seconds. ‘Is it really you, Andrew?’ said the officer, ‘We’ve been at our wits ends, looking for you all over Yekaterinsburg, and here you are in Perm.’ He blew his police whistle and that is how I happened to come here before you did.”

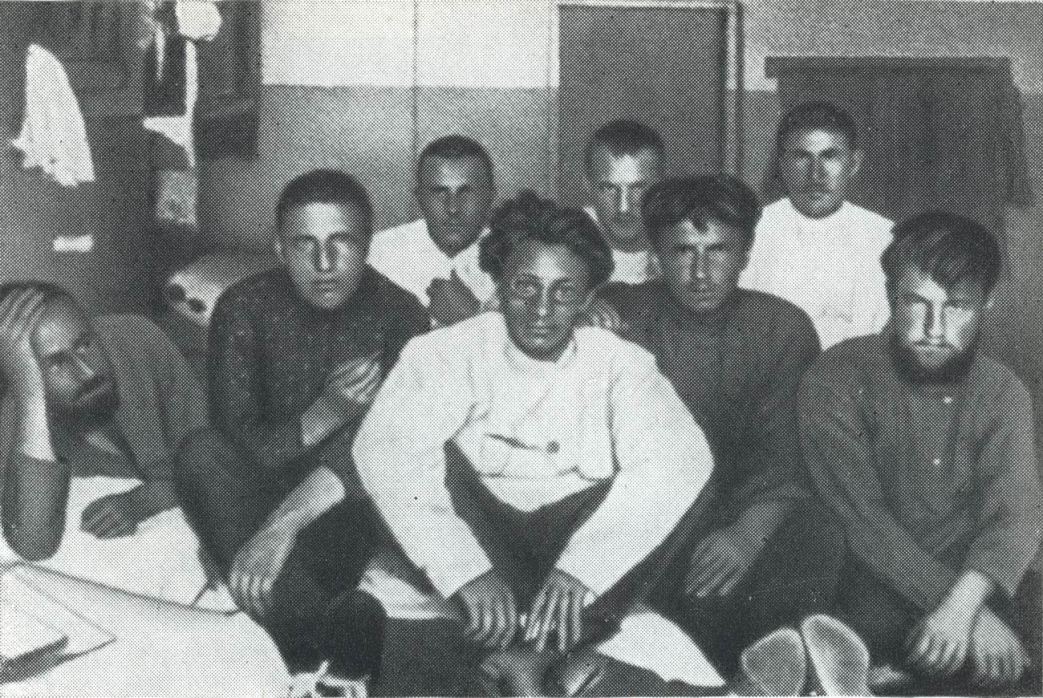

Scores of active workers of the Perm bolshevik organisation were arrested at the same time as Sverdlov, on June 10, 1906, including K. T. Novgorodseva, Sverdlov’s wife. A sensational case was manufactured, in preparation for which Sverdlov and the rest spent over a year in preliminary confinement, and in September, 1907, the Kazan court sentenced Sverdlov to two years’ confinement in the fortress.

During his preliminary confinement and while serving his term in the fortress, as far as was possible under the prison regime, Sverdlov read a great deal, studied revolutionary theory, and never for a moment abandoned the idea of revolutionary work to be done by him on his release from prison.

IV. PERIOD OF REACTION

In his article What We Must Struggle For, written in the beginning of 1910, Lenin worded the problems which faced the bolsheviks at the time, in the following way:

“By means of the struggle of December (1905) the proletariat left the people one of those heritages which can be ideological and political beacons for the work of several generations. And the darker are the gathering clouds of savage reaction, the greater the brutalities of the counter revolutionary tsarist Black Hundreds the more energetically must the workers’ Party recall to the people what they must struggle for.”

“We must know how to carry on our line of tactics, we must know how to build our organisation in such a way as to take into account the changed situation, not to lessen the tasks of our struggle-not to reduce them, not to belittle the ideological and political substance of even such work which at first sight seems most ordinary, dull and petty…

“Only by placing the tasks, bequeathed to our generation by the year 1905, in all their plenitude, in all their greatness before the masses, will we actually be in a position to extend the basis of the movement, draw large masses into it, inspire them with the feeling for supreme revolutionary struggle which has always led the oppressed classes to victory over their enemies.” (V.I. Lenin, “What we must Fight for,” Collected Works. Russian edition. Vol. XIV, pp. 266-267.)

Sverdlov could, better than anyone else, build the Bolshevik Party organisation, no matter how difficult were the conditions under which he had to build, and we see that, after three and a half years of prison, without giving himself any time for rest, he came to Moscow illegally, in the capacity of a “fresh man,” as it was called then in bolshevik circles, and began to collect and unite the scattered forces of the Party in Moscow as well as throughout the whole Moscow industrial region which, at that time, included fourteen provinces. Sverdlov tried to restore the Moscow committee and the Moscow regional bureau but Moscow was full of spies and he was not able to work long. He was arrested on December 13, 1909, during a meeting of the Moscow Committee. On being arrested Sverdlov gave a wrong name and presented a passport bearing that name.

In accordance with an order of the Minister of the Interior, Sverdlov was exiled to the Narym region and the chief of police of Moscow was instructed on March 17th to see that the order was carried out.

Sverdlov was very ill at the time, as is witnessed by the certificate of the medical examination signed by a doctor attached to the Arbat police cells, although the prison doctor, Kolesnikov, purposely tried to make as little as possible of his symptoms: Sverdlov, aged 25, averagely nourished, somewhat irregular of build (narrow chest), complains of cough, night sweat, hemoptysis; an examination of the left lung shows expiration a dry rattle. On the strength of the aforesaid symptoms I believe that Sverdlov suffers from a chronic catarrh of the top of the left lung, evidently of a tubercular nature.”

But documents show that, notwithstanding illness and the great distance, Sverdlov succeeded in escaping from exile.

“In their report of October 15th, No. 2277, the authorities of Ketsk informed me (Tomsk district police officer) that Yakov Mikhailovich Sverdlov, who was under open police surveillance, had disappeared from his place of exile in the Ketsk region on July 27th and that his whereabouts are unknown.

“I have sent instructions to the police officer of the fifth section of Tomsk district, under No. 1897, to search for Sverdlov in the Narym region. “In case the search within the limits of the said region proves fruitless, the search reports will be presented.

“I hereby report to your Excellency to that effect.

“Original duly signed.”

It may thus be precisely established that Sverdlov made his first escape from Narym in July, 1910, and from then on he undertook a series of escapes, the detailed description of which might serve as vivid data for a special book of adventures. In order to acquaint the reader of this short essay with some of the difficulties attending such an undertaking as escape from tsarist exile, we may note a few of the circumstances of the escape made by Y.M. Sverdlov in the autumn of 1912.

In a confidential note of the Petersburg secret police, addressed to the police department, dated November, 14, 1910, No. 15942, only five months after Sverdlov’s first escape from Narym, we read as follows:

“In the latter days of this year, this office has had information of the arrival from abroad of an agent of the Central Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, an individual named Mikhail Georguiesvich Permyakov–Party name “Andrew,” from the town of Kungur, Province of Perm, with instructions to restore the local Party organisation.”

In view of constant failure in Petersburg, the Central Committee advised “Andrew” not to enter into relations with old Party workers in Petersburg and to be as secretive as possible.

On his arrival in Petersburg he was indeed very careful and was taken under surveillance only in the beginning of November under the alias of “Makhrovy.”

A confidential note, dated November 19th, of the same year, No. 16143, states that ” on being questioned in the police office, Permyakov admitted that he was actually a middle-class citizen of the town of Polotsk, Yakov Mikhailovich Sverdlov, was prosecuted by the Perm provincial gendarmerie office under article 126, in 1906, was tried and sentenced to two years’ imprisonment in the fortress and served his term. In 1909 he was exiled for three years to the Narym region for belonging to the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party and from there disappeared.”

What did Sverdlov do in Leningrad, or Petersburg as it was then called, in those short months from the summer to the autumn of 1910? He was first of all busy, as he had been in Moscow in 1909, collecting the forces of the illegal bolshevik organisation, for the reinforcement of which he had to fight hard in the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party which was formally still a single body. He fought the Menshevik liquidators who considered that the time had come when only legal forms of struggle were possible, that illegal organisations in the Party were an anachronism and ought to be liquidated. While reinforcing the Petersburg illegal organisation in every possible way, Sverdlov also made use of the legal possibilities extensively.

He led the Bolshevik section of the social-democratic faction in the Duma in the speeches made in the Duma and before the workers’ electors at factories; at the same time he tried to secure bolshevik leadership in the legal newspaper which the faction proposed to publish.

After spending a month in prison he was sent back to his place of exile, but the rebellious spirit of “Makhrovy,” alias “Malish,” gave no rest even then to the “servants of the Tsar,” as the following document will show:

“Reference: In his letter of June 15, 1912, No. 1826, supplementary to the letter of May 15th last, No. 1454, the governor of Tomsk informed the police department that in connection with the demonstration made on April 18th of this year by the exiles in Narym, the gendarmerie authorities arrested for state custody in accordance with the rules, Yakov Mikhailovich

Sverdlov and that, in accordance with the statement of the chief of the Tomsk gendarmerie office, on examination of documents found in the possession of the said individual, sufficient reasons will probably be found for formally prosecuting him in accordance with the rules of act 1035, a crime provided for in article 121 of the criminal code.”

But no signs of the crime provided for in article 121 were evidently to be found and the authorities were content with making his exile more severe by sending Sverdlov with two guards to an out-of-the-way Ostyak village called “Maximkin Yar,” where the guards themselves became melancholy. Sverdlov immediately took advantage of their depressed state of mind. He succeeded in convincing them that this kind of life was impossible, they harnessed a horse to a cart and drove their prisoner to town. Having safely reached it, they fell on their knees before the local police officer and insisted that “Maximkin Yar” was not a fit place to live in. The police officer relented, at the same time allowing Sverdlov to remain in the town. After many unsuccessful attempts, as we shall see later, he escaped from this town.

V. PERIOD OF REVOLUTIONARY UPSURGE AND WAR

“The three years from 1908 to 1910 were a period of extreme counter, revolutionary activity of the Black Hundred, of liberal-bourgeois apostasy, proletarian dejection and disintegration.

“But a noticeable change became evident in 1910. In 1911 the masses began gradually to prepare for the offensive. There were indications on all sides showing that the fatigue and apathy caused by the triumph of counter-revolution were almost over, that the masses were again being drawn towards revolution.”

So V.I. Lenin wrote in June, 1912, and even before that, in January, 1912, a Party conference took place in Prague, at Lenin’s initiative and under his leadership, at which a final organisational division from the Mensheviks was declared, a clear Bolshevik line worked out on all questions of Party work in Russia and a Bolshevik central committee of the Party was elected.

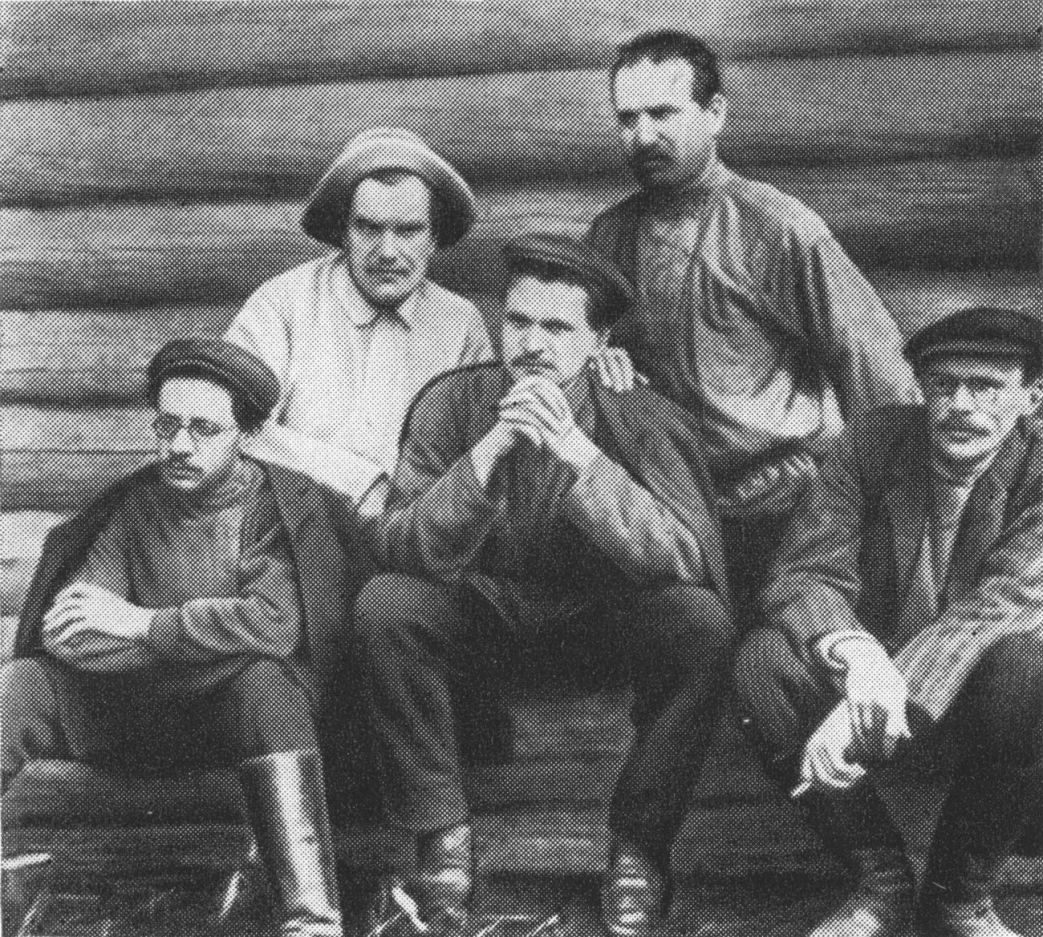

Two of the leading organisers of the Party, Sverdlov and Stalin, who were then exiled to Siberia, but whose escape was expected soon, were elected to this new Central Committee.

Stalin and Sverdlov were the two Bolsheviks in whom Lenin placed particular confidence with regard to carrying out the most important resolutions of the Prague Conference.

From April and May, 1912, the revolutionary upsurge manifested itself in a series of very big strikes and in demonstrations in all the proletarian centres of Russia. That was the time when, in reply to the shooting of strikers at the Lena gold fields in Siberia, the workers of the Dnieper-Petrovsk plant, situated ten thousand kilometres from that place, issued the following splendid expression of the solidarity of the proletariat: “It is our breast, the breast of the whole working class, which was shot through in the distant Siberian forest.”

The development of the movement demanded that the Bolshevik Party exert every effort, strain every nerve, and the forces of Sverdlov and Stalin were, naturally, absolutely necessary at the time; they escaped from Siberia at about the same time, but by different means.

Sverdlov’s first plan of escape was to cross the wide and stormy Ob River in a little canoe, to Novalinsk village, situated at a distance of thirty kilometres from his place of exile, there to board the steamer Tyumen where there were friends in the engine-room, who could conceal him. He undertook this expedition on a cold autumn night; a storm broke and the canoe was upset by the waves. Sverdlov and the comrades who were with him were thrown out and had to swim for three kilometres, holding to the sides of the boat until they were seen by some fishermen who saved them.

Despite this mishap, however, having dried his clothes and warmed himself, Sverdlov continued on his way and reached the steamer. After a hundred kilometres’ journey on board, when he thought himself safe, he was recognised by the authorities, taken off the steamer and brought back to his place of exile. A short time after this unsuccessful attempt to escape, Sverdlov’s wife, K.T. Novgorodseva, came to visit him in exile bringing his little son Andrew.

The police felt sure that with his family beside him Sverdlov would become more settled and not make any more attempts to escape for the time being. They therefore relaxed their vigilance. It never occurred to these policemen that Sverdlov’s wife had come to bring him all that was necessary for the planned escape. A week after the arrival of his wife and child, Sverdlov succeeded in escaping.

Even now, twenty years afterward, Comrade Novgorodseva-Sverdlova laughs as she remembers how, in 1912, when the police raised the alarm on discovering Sverdlov’s disappearance, she had to play the difficult role of a duped wife, whom with her child her husband was supposed to have abandoned to their own devices a week after they had with so much difficulty reached distant Siberia.

Comrade Novgorodseva had no intentions of remaining for any length of time in Siberia mourning for her lost family happiness. She hurried back to Petersburg where her supposedly deceitful husband Sverdlov had arrived before her. There he served as member of the Central Committee, in constant communication with Lenin; he had already accomplished a great deal of work, especially in connection with the legal bolshevik daily paper Pravda, which was then published in Petersburg.

V.I. Lenin attached particular importance to the Pravda as his following words testify: “By arranging for a daily workers’ paper, the Petersburg workers have done a great, and it may be said without exaggeration, a historic thing…The creation of the Pravda is an outstanding proof of the class-consciousness, energy and solidarity of the Russian workers.” (V.I. Lenin, Collected Works. Russian edition. Vol. XII, P. 241.)

The Pravda on the one hand and the Social-Democratic faction in the fourth Duma on the other, were the two main legal mediums which could be used for carrying on illegal revolutionary bolshevik work. But at the time Stalin and Sverdlov came to Petersburg, no bolshevik clarity was evident in the work. Only after Stalin and Sverdlov had come to Petersburg, only with their help was the split of the Social-Democratic parliamentary faction which had first consisted of Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, at last accomplished. The Mensheviks stopped using their conciliatory speeches to block the group of Bolsheviks who now acted independently, launching slogans from the parliamentary tribune for the masses. The most popular slogans at the time were the three which the Petersburg workers called the three whales–the eight-hour working day, confiscation of landlord’s estates and a democratic republic.

Both Stalin and Sverdlov spent much labour and exertion setting the Pravda along bolshevik lines; they carried on an active correspondence with V.I. Lenin, who, until their arrival, had constantly and unceasingly reproached the editors of the Pravda for vagueness and lack of concreteness on basic questions of struggle.

All this time Sverdlov lived in the apartment of Badayev, a deputy of the Duma, never leaving it day or night, looking through manuscripts, writing extensively himself, instructing the deputies who came to see him, directing their speeches, organising the struggle against Menshevik liquidators, etc.

But this time too, neither Sverdlov nor Stalin got the chance to work long. As is known, the tsarist police department succeeded in getting one of their agents into the Bolshevik parliamentary faction. Malinovsky was an agent provocateur and he did not hesitate to deliver into the enemy’s hands the men who were so necessary to the revolutionary cause–he betrayed Stalin and Sverdlov.

We find interesting details of Sverdlov’s and Stalin’s arrest in the memoirs of Badayev entitled: Bolsheviks in the Tsarist Duma.

The house janitor came one day to Badayev’s apartment and having described Sverdlov’s appearance, asked whether such a person was not staying in the flat. Badayev naturally answered that there were no strangers at all in his flat. But after that it was not safe for Sverdlov to hide in Badayev’s flat. It was decided to transfer him to another house that same day. After plans had been made, that night, Badayev and Malinovsky went out into the street to see that everything was safe. There was no one around, so Badayev and Malinovsky lit a cigarette each, this being the signal agreed upon. Sverdlov answered by putting out the light and letting the window down. After waiting for a few minutes he came out into the yard. Badayev and Malinovsky helped him over the fence, then Sverdlov climbed another fence and came out on the quay, where a cab hired previously was waiting for him.

Sverdlov went to Malinovsky’s flat and from there to Petrovsky’s flat. There he was arrested that same night. Malinovsky, who had seemed so “anxious” for Sverdlov’s safety, gave the secret police the address of the flat where Sverdlov had found refuge.

It was during that time too that Malinovsky betrayed Stalin who was also in hiding and never appeared in the street. A concert was being arranged in the Kalahnikov stock exchange building, the proceeds of which were to be used for the publication of Pravda as well as for other revolutionary purposes. The Sympathetic intelligentsia and workers usually came to these concerts in great numbers. Members of the Party who lived legally came also, and even illegal workers were wont to attend, for there they were able to mingle in the crowd and talk with the people they wanted. Malinovsky knew that Stalin would attend that concert and he informed the police as much. Stalin was arrested by the secret police that very night under his comrades’ eyes.

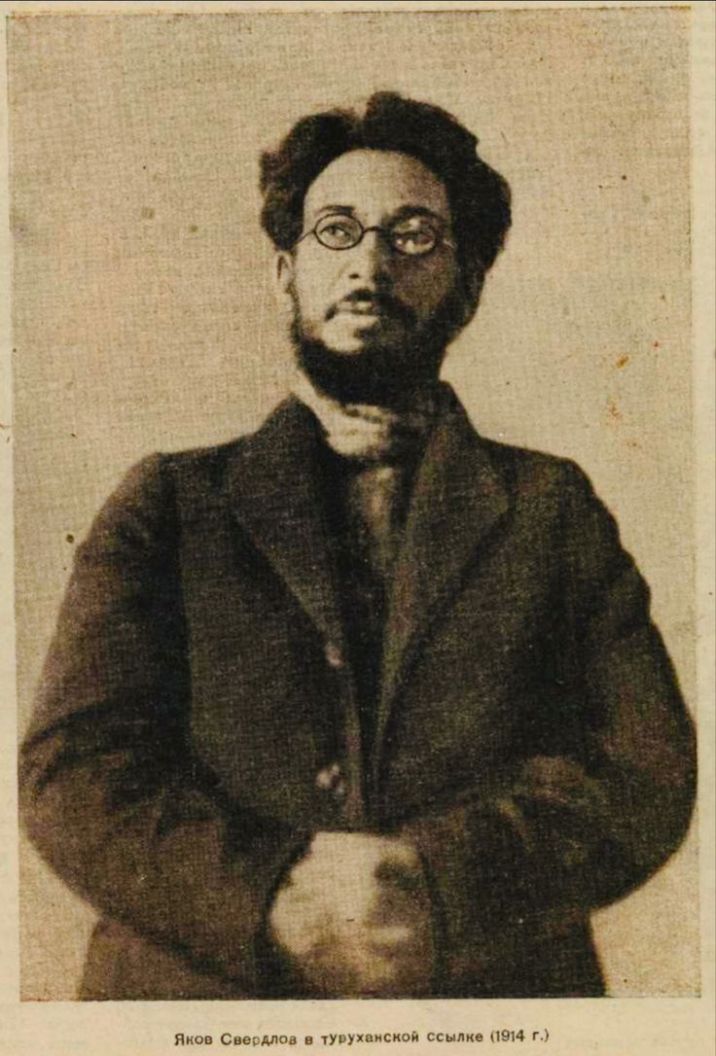

This time Sverdlov was confined to the “Kresty” prison with his wife and son and after a few months they were all sent to the Turukhansk region, whither Stalin also was sent soon after.

This last arrest and exile of Sverdlov occurred in 1913, when the tide of the Russian workers’ movement was rising higher and higher, especially in Petersburg. The climax was reached when barricades were erected in the summer of 1914 in the streets of the capital; but war came to overshadow all other things and it temporarily stopped the current of the Russian revolution as well. The struggle and victory of the workers were thus postponed for three years.

Sverdlov’s letter to his sister Sarah tells us of the place to which the tsarist’s government sent Sverdlov and Stalin after they had fallen into its hands. We quote the whole of it (there is a copy of it in the file). The address on the envelope is St. Petersburg, Ordinarnaya No. 6, Apr. 26, Sarah Nikhailovna Sverdlova, the post-mark-Turukhansk, 13-3-14.

“9-11. Dear Sarah: My next letter will be numbered again. I am writing just a few words now, hastily. Joseph Jugashvili and I are being transferred a hundred versts further north-eighty versts north of the Polar circle. There will only be the two of us in the village and two guards with us. The surveillance is being increased and we are cut off from the post. The latter comes once a month with a messenger on foot, who is generally late. We will get the post approximately eight or nine times a year and not oftener. Still it is better than it was in ‘Maximkin Yar.’ Please send everything to the old address, the comrades will forward it. Jugashvili is deprived of his subsidy for four months because he received some money. We both need money. But it cannot be sent in our name. Let our friends know of this. I have a debt and the money can be sent not to me but directly to my creditors. Let me know their address; Rom also has an address. Only the coupon must be marked ‘on account of Y.M.’s debt.’ I am expecting all I asked for. I shall write now from Kurepka. I am not writing to anyone in Petersburg except yourself, assuming they will learn from you.

With love,

“Your Yak.

“Write more, and oftener. I ask all friends to do the same. I did write to a few people in Petersburg after all. My address is the same.”

The reader will easily understand that all this talk of creditors, debts, etc. is only meant to conceal references to the necessity of getting money, passports and addresses for a new escape. But they had both been sent to such a distant place that all attempts at escape ended in failure, and they both had to stay at the edge of the world until the February revolution.

The above letter gives a clear idea of the conditions of life in that distant spot. But Sverdlov as usual, did not lose hope, he had too much to think of, too much to work over theoretically, to prepare himself and others for further struggle in the future. Sverdlov was fond of life, he always remained an optimist, his nature made it impossible for him to lose hope.

Sverdlov was also fond of nature. This may be seen from his description of an early spring in the far north, in one of his letters: The ice thaw on such a great river as the Yenissey is worth seeing. The ice breaks with a cracking noise, splits into enormous blocks. The blocks are driven against each other by the water, they strike against the bank while the water rises higher and higher. One is loath to leave the bank. The north wind rises, the waters of the Yenissey swell, become covered with foam, strike against the high bank on which the village stands, washing it away bit by bit, the earth falls with a great thud and is carried away by the waves.”

In another place he says:

“Since yesterday the sun has stopped setting. It shines the whole twenty-four hours round. There has been no darkness for a long time. White nights…the sun is always on the horizon. It is strange and unusual. You cannot tell night from day except by the direction of the sun. It is now eleven p.m. and the sun is right before my window. Only it is blood red and hardly gives any warmth. In contrast to this there is a lot of snow around. It melts and disappears with incredible slowness.”

In spite of the distance, Sverdlov kept in constant touch not only with exiled Bolsheviks scattered all over Siberia, among whom he was a generally recognised authority, but also with V.I. Lenin, with the centre of the Bolshevik Party abroad and through some comrades, with various local Party organisations, so that he was always in touch with current revolutionary events.

The numerous threads which always bound Sverdlov to the working masses, to the life and thought of the Bolshevik Party and to its leader, V.I. Lenin, never broke, wherever he might be, even were it beyond the Polar circle.

That is why, when the war broke out and so many were poisoned by chauvinism, when the Second International fell to pieces, when leaders engaged in open betrayal, Sverdlov who was many thousands of kilometres away from the centre had no difficulty in summing up the situation and never for a minute abandoned Lenin’s position. He read several lectures on war to the other exiles, wrote articles on international Social Democracy, and when he received news of the conferences of Zimmerwald and Kienthal on the first unification of internationalists he carried out in his lectures and articles the ideas of the Zimmerwald Lefts: the transformation of imperialist war into class war, and he set forth the tactics and strategy of civil war and dictatorship of the proletariat.

The great year 1917 came. News of the downfall of the autocratic tsarist regime came to Sverdlov in his exile.

VI. FROM THE FEBRUARY REVOLUTION TO THE OCTOBER REVOLUTION

THE great year 1917 came.

The Tsar’s throne fell under the impact of the uprisen proletariat, supported by the masses of the soldiers; but the proletariat had not yet come to power. The most peculiar feature of our revolution which commands the most insistent attention is the duality of power which obtained in the very first days after the victory of the revolution.

This duality of power consisted in the existence of two governments, the main, real and actual government of the bourgeoisie, in the “Provisional Government” of Lvov and Co., which held all the organs of power, and a supplementary “controlling” government of workers represented by the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies which did not hold the organs of state power, but was supported by the recognised majority of the people, by the armed workers and soldiers.

Thousands of kilometres away from the Party centre though he was, Sverdlov still kept a watchful eye on, a “thoughtful attitude” towards the revolutionary situation as it was then.

As soon as the joyful news of the fall of the monarchy reached Sverdlov in exile, he started off–to dive into the vivifying revolutionary waves; but, to his great disappointment, waves of another kind, occasioned by the Siberian spring flood, obstructed his passage. He had to hurry to leave Turukhansk, as the spring floods might otherwise cut him off from the centre of revolutionary events for some months.

In danger of being caught in the ice drifts, Sverdlov with a group of exiles travelled two thousand kilometres in sleighs over the ice of the Yenissey which was ready to break at any moment. And so he came to Krasnoyarsk.

In Krasnoyarsk, which is a large Siberian centre, the local Bolsheviks did not at once grasp the revolutionary situation fully and Sverdlov was the first to make matters quite clear, with a bolshevik concreteness, in his speech at the meeting of the plenum of the Krasnoyarsk Soviet, where leaders of all parties made speeches.

Such bolshevik precision does this speech typify, the questions are formulated with such concreteness that we cite the entire contents:

“Step by step,” writes Comrade Shumiatsky in his reminiscences about Sverdlov, “Comrade Sverdlov lifted the flimsy decorations and unmasked the squalid pseudo-revolutionary ideology of the speech of the Socialist-Revolutionary Koloskov, saying that the people whose name the Socialist-Revolutionaries like so much to use in vain, had so far gotten nothing from the revolution, except the soft-sounding speeches of men like Kerensky and Koloskov, that the Mensheviks put the workers and soldiers off with promises of tomorrow, thereby lowering the interest of the wide masses of the people in the progress of the revolutionary struggle. The revolution is the most acute moment of class struggle, in the course of which the socially. oppressed classes want the ruling classes to make concessions and if they don’t get them they take them by force. If the ruling class is not vanquished, then the revolution will be vanquished. That is why we Bolsheviks are against the slogan of civil peace of the revolutionary democracy, that is why we advance the slogan of irreconcilable class struggle, in the process of which the classes and groups which are interested in the victorious issue of the revolution will join it, while many of those called the best representatives of revolutionary democracy by the speaker for the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries will oppose the revolution.

“Experience shows that soviets constitute the best and only form of organisation for the victorious struggle of the working class and revolutionary peasantry. They are the headquarters of the army of the proletarian revolution, whereas the idea of civil peace, which Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries advocate is an attempt to hinder the successful development of the victorious revolution of the working class and revolutionary peasantry. Every coalition is the expression of this idea of civil peace, and is therefore an attempt to restore the forces of the bourgeoisie by deceit and thereby strengthen them.

“’That is why we, Bolsheviks, are against all coalitions and in favour of power passing into the hands of the working class and revolutionary peasantry represented by the soviets.’”

On returning from Siberia, Sverdlov went off to his beloved Urals and at the very first regional Party Congress, he, who used to be known as Comrade Andrew, collected around him his old Urals comrades with whom he had worked in underground Bolshevik work, and became the central figure of the congress and of the whole Urals regional Party organisation. In April he went to Leningrad as delegate of the Urals region to the All-Russian April Conference at which he was elected member of the Central Committee. The latter body would not allow Sverdlov to return to the Urals, but made him remain in Leningrad to work directly in the secretariat of the Central Committee.

From the time of the publication of the famous April theses of Lenin, Sverdlov centred his entire and tremendous revolutionary energy, his whole and extensive experience as organiser, on the question of winning the masses over and liberating them from the influence of conciliatory ideas.

Factory and works committees were suggested at that time as one of the organisational forms by means of which the masses in the factories might be brought under bolshevik influence. Sverdlov organised the first Leningrad conference of factory and works committees, was elected to the presidium and directed the work of the conference.

The masses were turning to the Bolsheviks more and more.

“Excitement in Petersburg has reached the greatest height, it is sufficient for a single shop in one of the big factories to make a demonstration and the whole population of workers and soldiers in the capital is roused. All we have been doing lately is to quench the rising flames since we do not believe direct action expedient at the present moment.” (From Sverdlov’s correspondence, The Press and Revolution, 1924.)

When the masses did come out into the streets in the days of July, Sverdlov was the first among them, at their head, although he thought such action premature. It was in those days that the bourgeoisie of all colours gave Sverdlov the nickname of “Black Devil.”

The campaign which the bourgeoisie organised against the Bolsheviks after the days of July, went to such preposterous lengths that Lenin was declared to be a German spy.

When Lenin had to hide and lead an illegal existence the Bolsheviks were of different minds as to whether he should not go before the Provisional Government to rehabilitate himself. Lenin himself wished to do so. Sverdlov and Stalin saved the situation; with great difficulty they persuaded Lenin not to do it. Thus they saved him for the cause of the proletarian revolution, for otherwise the bourgeoisie would have dealt with Lenin as it did with Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxembourg.

In the second half of July, Sverdlov was busy preparing for the VI Congress of the Party, which had to be carried out partly illegally. At the Congress he made a report on organisation on behalf of the Central Committee. The Congress took place in Lenin’s absence and the task of leading the conference and carrying out Lenin’s line fell upon Sverdlov’s and Stalin’s shoulders.

After the VI Congress, Sverdlov gave a great deal of his attention to mass work in the army and the Central Committee appointed him to direct the work of the military organisation.

October was near at hand. On October 8th (old style), Lenin wrote in an article entitled The Crisis Has Matured: “The whole future of the international workers’ revolution for socialism is at stake. The crisis is ripe.” (V.I. Lenin, Collected Works. Russian edition. Vol. XXI, p. 239.)

On October 10th, the Central Committee met with Sverdlov as chairman and an armed uprising and seizure of power was voted unanimously by all the members except Kamenev and Zinoviev.

Sverdlov, Stalin, Dzerzhinsky, Bubnov and Uritsky were elected for the practical centre in the organisational direction of the revolt. In the days of the revolution itself Sverdlov worked on liaison service, was a member of the insurrectional commission of the Central Committee, watched the Provisional Government and its decrees, kept in constant communication with the Peter and Paul Fortress, sent coded telegrams, instructions, etc.

Full of revolutionary energy and fearlessness, Yakov Sverdlov brought a cheerful and hopeful feeling everywhere. “Kerensky will be beaten, we shall meet in the Republic of Soviets,” wrote Sverdlov in his orders and appeals.

The victory was won. Kerensky’s government was destroyed. On November 8th, Sverdlov was elected the chairman of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the Soviets.

VII. AFTER THE OCTOBER REVOLUTION

COMRADE STALIN describes Sverdlov’s work from 1917 to 1918 in the following way: “The period of 1917-18 was a crucial one for the Party and the State. The Party at that time became for the first time a ruling force. The new power-the power of the Soviets, the power of workers and peasants arose for the first time in the history of mankind. To transfer the Party, which had been until then illegal, to new rails, create the organisational basis of the new proletarian state, find the organisational forms of interrelations between the Party and the Soviets, secure leadership for the Party and the normal development of the Soviets these were the complicated organisational problems which then faced the Party.

“No one in the Party would have the courage to deny that Y.M. Sverdlov was one of the first, if not the first, who skillfully solved these organisational problems, essential to the construction of a new Russia.

“The ideologists and agents of the bourgeoisie are fond of repeating trite phrases to the effect that Bolsheviks do not know how to build, that they can only destroy. Y.M. Sverdlov and his whole work are a living refutation of these stories. Y.M. Sverdlov–his work in our Party is not accidental, the Party which has produced such a great builder as Y.M. Sverdlov can safely say that it knows how to build the new as well as destroy the old.” (Symposium in Memory of Sverdlov, p. 58.)

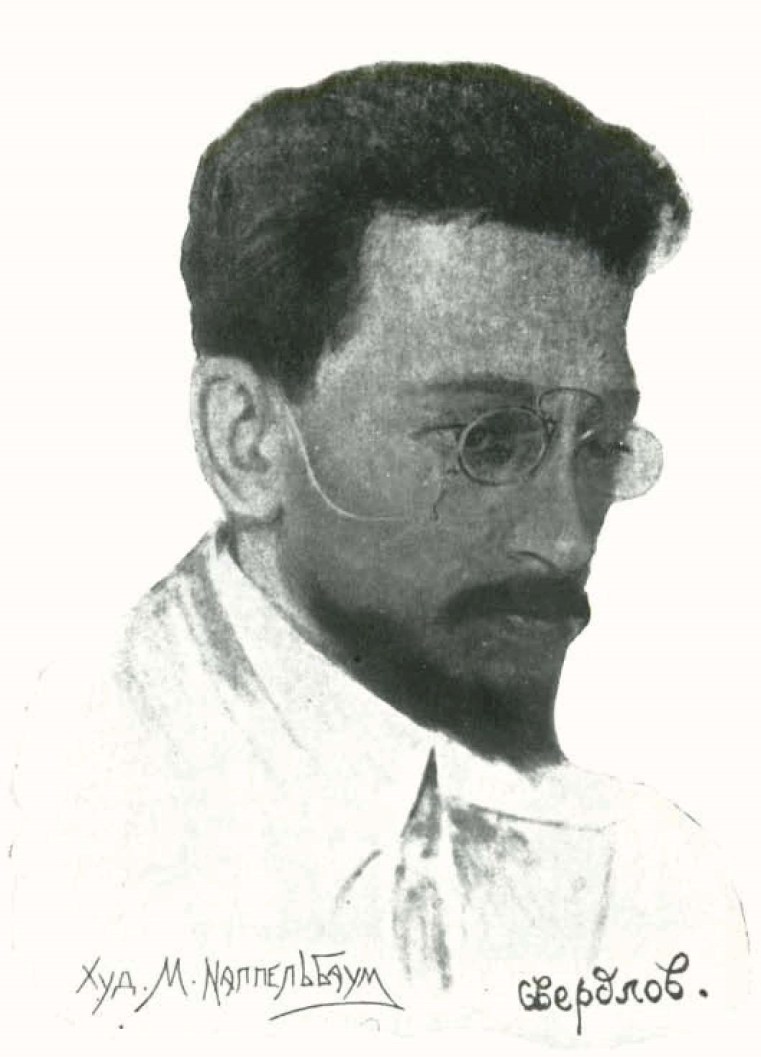

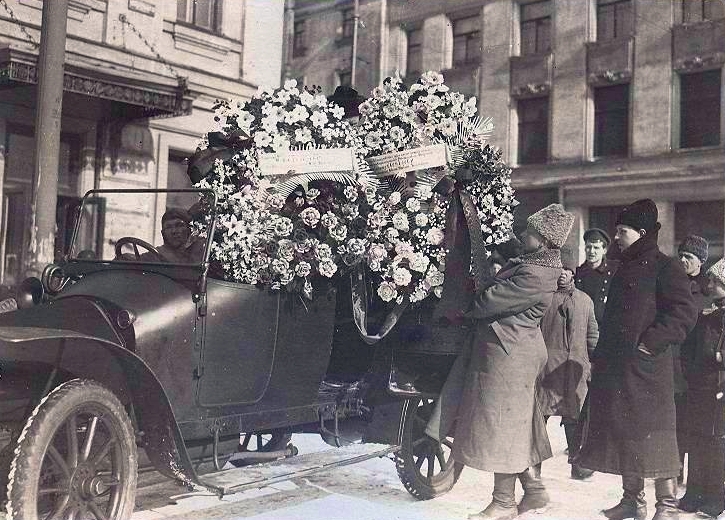

From March, 1917, when Sverdlov, full of strength and energy, hurried from his exile in Siberia to the centre, up to March, 1919, when, during his last journey from Kharkov to Moscow, he caught a severe cold which caused his death, only two years went by, but such years as those can be compared to decades.

The shortness of this essay does not allow us to give even the most general outline of the varied creative work which Sverdlov did at the time under Lenin’s direct guidance, on the reinforcement of the ranks of the Bolshevik Party, creating and reinforcing Soviet Power in the centre and different localities, fighting against inner counter-revolution, organising the defence of the achievements of the revolution from the interventionists of all denominations, from inner and international whiteguards.

Sverdlov’s activity, such as his historic speech at the Constituent Assembly on January 5, 1918, the whole part he played in the Soviet period, demands a special independent research and we shall close our essay with the words of Lenin from his speech over the grave of Y.M. Sverdlov:

“The proletarian revolution is as strong as the strength of its sources. In the place of those people who have given up their lives to the revolution in an act of supreme fidelity and fallen in the struggle, it advances whole ranks of others, perhaps less experienced, less prepared, but people who are connected with the wide masses and who are able to continue their work in place of the great talents which are gone.

“In this sense, I firmly believe that the proletarian revolution in Russia and in the whole world will bring forward group after group of people, will bring forward many sections of the proletariat and toiling peasantry, who will give that practical knowledge of life, that both individual and collective talent for organisation without which the vast army of proles tarians cannot achieve their victory.” (Lenin, Collected Works. Russian edition. Vol. XXIV, p. 83.)

Workers Library Publishers replaced Daily Workers Publishers as the main pamphlet printing house of the Communist Party in 1927. International Publishers was originally meant to translate works into English, but became the CP’s main book publisher.

PDF of pamphlet: http://palmm.digital.flvc.org/islandora/object/ucf%3A5429/datastream/OBJ/download/The_first_president_of_the_republic_of_labour__A_short_biographical_sketch_of_the_life_and_work_of_Y_M__Sverdlov.pdf