Austin Lewis was the leading Marxist theorizing industrial unionism in the United States before World War One. Among his most important works, meant to become a book, were a series of articles on on the politics, economy, and psychology of ‘solidarity’ for the New Review. Here, he investigates the material ‘mechanics’ of solidarity with a focus on the unskilled worker, often considered ‘lumpen’ by their skilled or educated counterparts.

‘The Mechanics of Solidarity’ by Austin Lewis from New Review. Vol. 3 Nos. 18 & 19. December 1 & 15, 1915.

SOLIDARITY cannot be regarded as the result of a propaganda. No amount of preaching of solidarity will bring about the fact. No altruistic campaign to persuade the better established working class into lending aid and comfort to the less favorably placed in the struggle with the employer will achieve results.

Altruism has, however, heretofore formed the basis of such appeals as have been made to the better paid portion of the working class on behalf of those others. No wonder it has not succeeded. Altruism is no more appropriate to the labor movement than to any other of the economic and industrial departments of human life. A comparatively well-to-do artisan will not put himself out on behalf of an unskilled workman any more than a well-to-do trader for a small business man, unless by so doing he actually and directly benefits himself.

We have seen that such efforts as have been made by the crafts towards the organization of migratory labor and the unskilled have had the well-being of the crafts in view rather than that of the unskilled who were the hypothetical beneficiaries.

This does not attribute any particular hard-heartedness to the crafts. It merely shows the sufficiently obvious fact that the members of the crafts are human beings, subject to the same laws as other human beings, and that their own economic security and well-being are their prime considerations.

Solidarity, like all economic and political progress, must come from below, not from above. The crafts will not help the unskilled; hence it follows that the unskilled must help themselves.

But why did the unskilled not help themselves long, long ago? What reasons have we for supposing that they are more likely to struggle towards their emancipation to-day than hitherto? The unskilled could not hitherto have made a coherent and justifiable attempt at self-emancipation. On the contrary, the conditions which would render such a struggle at all feasible are only just beginning to appear.

If economics, as Hegel said, belong to the category of history, all the manifestations of proletarian struggle belong also to the same category. No manifestation of any value can take place until the economic and industrial environment is suited to the production and development of that manifestation. We have seen the rise of premature proletarian movements posited on some fine sounding theory, the said theory in itself containing much truth. We have seen also the disappearance of the same movements accompanied by an inordinate amount of suffering and disillusionment which might otherwise have been saved. The statement of Marx in his Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte unavoidably recurs in this connection. Says Marx:

“Proletarian revolutions…criticize themselves constantly; interrupt themselves in their own course, come back to what seems to have been accomplished in order to start over anew; scorn with cruel thoroughness the half measures, weaknesses and meanesses of their first attempts; seem to throw down their adversary only in order to enable him to draw fresh strength from the earth and again to rise up against them in more gigantic stature; constantly recoil in fear before the undefined monster magnitude of their own objects–until finally that situation is created which renders all retreat impossible and the conditions themselves cry Hic Rhodus, hic salta.”

Without committing one’s self to the apparent catastrophism of the latter part of the statement this continual tendency on the part of the labor movement to retrace its steps and to double back upon itself is a very well established phenomenon. Now and again the theory pushes ahead of the facts, and the abstraction produced makes a false dawn which the facts themselves in the long run dispel.

The position of the social democratic movement with respect to the present European war is an instance of just this sort of mistaken enthusiasm. The social democrats were so certain that their political and anti-military propaganda was destined to prevent a European War that, when the circumstances arose which called for their active intervention, they were paralyzed and horrified at the discovery that they had no real power. The fact that there was no real solidarity of labor in the political propaganda, and that the craft organization of industry gave them no control over the industry, was taught by one order of mobilization more completely than by all the arguments of all the syndicalists through many energetic years. Only one thing could have stopped that war, the solidarity of labor. Such solidarity is a fact and not a theory, a fact which must ultimately confront the governments and which, of itself, would be the most complete safeguard against international war.

Such solidarity results from other economic facts and is the product of automatically working factors in industrial life. It is not to be had for the preaching or the wishing. No sleek orator can evolve it from the sinuosities of tortured speech. It is not made; it proceeds.

Let us consider the question of the former inability of the unskilled to help themselves, that is to get such standing ground as would enable them to make a contest on their own behalf against the employer, on the one hand, and to impress themselves upon the rest of the organized trades on the other.

The relation of the unskilled to the trades has not been unlike that of the trades to the small bourgeoisie. The young man who started out too poor to afford apprenticeship and whose position in the social scale was such as did not entitle him to the advantage of a trade, looked forward to learning such trade as an ultimate or taking advantage of the amount of free land and the frontier, went forth to establish himself in the wild. The social gulf between the skilled and the unskilled man has always been greater than can be understood except by those who have had actual experience of it. The small bourgeois had his small property or his small business, the craftsman had his craft, property also, but the unskilled had nothing but physical strength which was useless as a basis of organization under an economic system which constantly dissipated it. Where industry rested on a basis of skill, that is specialized craft training, the possessors of that skill controlled the labor side of the controversy. For they alone had the power of actively interfering with the process of production on the labor side. They were the only people with whom the employers could treat. Indeed, they were the only persons with whom it was possible to make treaties, for they were the only persons who could organize and make organized demands. Since these organizations were possessed of a certain property, namely, skill, they made agreements with the employers in terms of property, that is, they made contracts. By these they agreed to employ their skill property regularly for an agreed length of time in accordance with certain agreed conditions.

This state of things marks the position of the American Federation of Labor; it is in fact the justification of as well as the reason for its existence.

It is very clear that the unskilled had, under these circumstances, no opportunity for organization. They had indeed no mind for organization for there was clearly nothing in terms of which they could organize. It is true, that attempts were made to organize them at times, such as that of Joseph Arch to organize the agricultural laborers of England. But such efforts were spasmodic, transitory, and doomed to be unrelated to the great labor struggle. It is evident enough, as it is historically true, that organizations of unskilled labor could not be created where the conditions involved the employment of isolated groups of unskilled, or where the skill of the artisan was the principal factor and the work of the unskilled was entirely subsidiary to and dependent upon the skilled.

This was recognized by the Socialist writers who apply the term “labor” exclusively to that skilled labor which they consider capable of organization. The labor movement to the average Socialist is the organized trade union movement, the organization of the skilled. Outside of this the mass of the unskilled are contemptuously regarded as “Lumpenproletariat” and generally classified as riff-raff and unorganizable material.

Up to now the foregoing has been generally true. Such being the case, criticism of the unskilled for failure to organize falls in face of the fact that the unskilled could not organize because there was no real basis on which they could organize.

Attempts to organize on the same basis as that of the skilled have been made repeatedly, only to fail. These failures have been charged against the unskilled, and leaders who have busied themselves with these organizations have retired disgusted from the task. They have covered their defeat by proclaiming that the unskilled are too stupid for organization.

Ignorance and stupidity are the eternal obstacles to organization and form the burden of complaint of all whose business it is to teach and discipline. It may be granted that large numbers of the unskilled owing to their disadvantageous economic conditions are lethargic and impervious to an intellectual appeal. But this obvious ineptitude is merely relative. The skilled are quite as unreceptive to an appeal which is purely intellectual. So also it may be said are stockbrokers, university men, lawyers and the clergy. Outside of their own immediate environment and except when the impact upon their material conditions is very manifest they are all deaf to the intellectual appeal. Pure “reason” plays a very insignificant part in human relations and leaves the vast mass of mankind quite untouched. Perhaps there may be some truth in the statement that the unskilled are as a body more stupid than the mass of men, but there is no proof that such is the case.

Intellect, pure reason, ability to think, none of these have much connection with the basis of organization. Obvious self-interest is the basis.

In the organization of labor the motives are so plain and the results to be attained so material that very little demand is made on the reason. Had it been otherwise we should certainly never have seen the organization of the crafts.

They organized because their interest in organization was plain. The material prospects of such organization, reduction of working hours and in- crease of pay were easily recognized. The organization promised these results. Hence the crafts organized even under conditions which appeared to render these results remote in many instances and which required immediate sacrifices.

Indeed, their actions have shown so slight a grasp of the situation on the intellectual side that the results which they have regarded as their objective were as a matter of fact but partial results. For a diminution in the number of hours worked may be offset by a greater intensity of labor during those working hours and an increase in pay may obviously be counterbalanced by an increase in the cost of living. These results have actually occurred and could have been easily foreseen with a slight amount of thought, of which, however, the organizers were entirely and satisfactorily innocent.

Ignorance and stupidity were no bars to the creation of the organization of the crafts, neither has the perpetuation of such stupidity been any bar to their growth. They have not been the factors which up to now have prevented the development of the organization of the unskilled.

The unskilled have not organized because they had no apparent reason in organizing, and to tell the truth they have had no reason to organize until the present. With the crafts in control there was no chance for the unskilled.

The unskilled worker’s only hope was to get out of his class in some way or other. He had no lever by which he could move the crafts and the employers simultaneously, and thus pry away the rocks which lay between him and the free air.

The employers pointing to the unorganized and hungry masses threatened him with extinction if he contested. The organized employees, pointing to the same masses, could afford to smile at any attempt to create an organization out of the inferior and shifting material which formed the bulk of unskilled labor and through which the militant unskilled had to force his way. On the one hand, the cheapness and plentifulness of unskilled labor was the greatest enemy to itself; and on the other hand, the employer could afford to ignore the effort of the unskilled be. cause his business was based upon a contract with the skilled. As long as he could hold skilled labor either in the “free” or union form he was secure. Thus we have many times seen the engineers and conductors ruin the chances of the more unskilled railroad employees. Frequently those trades which have had contracts respecting certain technical processes in mining and manufacture have contemptuously stood by and seen the unskilled beaten to their knees and have indeed helped to beat them. The stories of the attempts of unskilled labor to achieve organization and to gain a fighting ground have a wearisome and disgusting sameness. They are a record of blood and tears.

As regards these movements the claims of solidarity have so far been but faintly recognized and as a matter of fact they are largely mythical. No solidarity and for the most part not even the barest vestiges of ordinary humanity have been shown, until very recently, by the skilled crafts for the efforts of the unskilled. Indeed as far as any sympathy has been shown for the latter by the former, the unskilled might as well have been Kaffirs.

Moreover, the group which was in a position to make contracts with the employers prided itself upon that fact. Its members rejoiced that they occupied an intermediary position between the employer and the mass of ordinary labor and gave themselves, airs in consequences. They considered, and, indeed advertised themselves, as a distinctive class. Some of them were recognized by the employer as especially his adherents, as it were his janissaries, upon whom he could rely as a defence against the attacks of predatory labor on the outside.

Under such conditions the difficulty, nay the impossibility, of the organization of the unskilled be- comes at once manifest. No amount of intelligence could have altered these actual conditions, no conceivable sentimental altruism could have caused the aristocrats of labor to turn a friendly eye towards the organization of the helpless unskilled.

Their outlook was dark. The entrenched trades looked down upon them with contemptuous indifference, more callous and coarse because more ignorant than the contempt of the aristocrat for the bourgeois.

But as those who were unable to fit into the narrow groove of the earlier village life wandered off and built new empires, so the play of economic forces was in time to bring a condition in which the unskilled would have the shaping of labor’s destinies. Under the old system of industry in which the crafts had the determining voice the very uncertainty of the life of the unskilled endowed him with ne’er do well qualities in the eyes of the respectable, however hard he might actually work. Indeed the very same stigma is today implied in the term “migratory laborer.” It is very manifest in the more ordinary expression “hobo.” And just as the new nations derived their origin from the efforts of the outcast and the disreputable to a much greater extent than their respectable successors will admit, the future of labor becomes henceforth more closely identified with the progress of the unskilled.

It is true that long ago, even in the eighties, the dock laborers of London won international fame and set Mr. John Burns on the highbroad to the British cabinet by a mass strike of the unskilled. The gas workers also formed an organization and, although coming under the category of unskilled labor, more than held their own in the struggle.

Everywhere in the advanced countries those who were formerly regarded as unskilled riff-raff began to assert themselves and to show their ability to organize. In many cases their attempts failed after a few efforts, in others something like an organization was formed. This as a rule attached itself to the dominant craft-union organization and went through various vicissitudes, some of them none too creditable. “Federal unions” so called sprang into existence only to subside, besmirched frequently with corruption of one sort or another. Labor organizations which attempted to deal with labor en masse in- stead of with several departmental crafts were talked about. In fact, the speculative field of the labor movement was littered with all sorts of schemes, more or less visionary, for the organization of labor as a whole.

For a time these merged themselves in the socialist movement. The socialist’s breadth of teaching his all embracing democracy and idealistic visions impressed the imagination of the agitators. The poets and philosophers of the unskilled therefore threw themselves ardently into the socialist movement so that for several years the socialist platform was a curious and discordant discord of the aspirations of the unskilled and the wailings of the unsuccessful small bourgeois. The absence of the skilled work- man from the Socialist movement was indeed in those days quite marked and was so bitterly resented by the socialists of that time that they made vehement attacks upon the “pure and simple A.F. of L.” and covered its leaders with abuse largely undeserved.

But the entry of the Socialist Party upon an attempt at serious politics changed the whole situation. The unskilled very soon discovered that they were, for the most part, without that essential political asset, a vote, and were consequently not objects of solicitude to the politicians. “Labor” to the Socialist movement began to mean organized labor or at least such “labor” as could be converted into votes. The unskilled were now assailed with the same epithets as had been applied to them in Germany and elsewhere. He was told very plainly that he must consider himself a very inferior fellow and was certainly and swiftly relegated to the rear.

But it will be observed that all this time the unskilled were becoming recognized. The fact that they were abused shows this. They were beginning to play a role in the great movement. It is true that it was by no means a brilliant role, really quite insignificant. Here and there however appeared movements of the foreign, forlorn, and apparently hopeless workers of the unskilled even of the migratory unskilled, whose advent was received with screams of abusive derision from the most orthodox and conventional of the Socialist politicals.

These movements sometimes, as at McKees Rocks, gained a temporary and precarious triumph. Here the unskilled having at great sacrifice made notable gains were driven from their position by American workingmen who could not endure the sight of foreign and despised labor achieving any position.

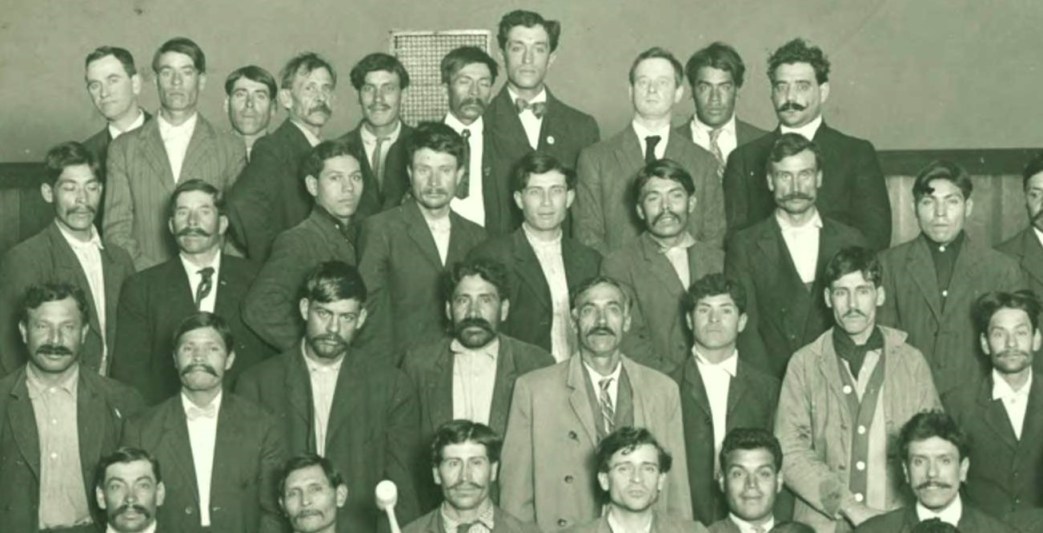

Exposed at every turn to incessant hostility, denied the most elementary constitutional rights, harried by constables and magistrates, ridden down by mounted police and shot by deputy sheriffs, the feeble unskilled gradually and slowly and with much expenditure of blood and suffering was transformed into the militant unskilled. And this militant unskilled differentiated itself from, arose out of and stood above the sluggish torpid mass.

The organized crafts thereupon began to notice the unskilled. They feared but despised the movement, and from the first have approached the question as a problem affecting not the unskilled primarily but the organized skilled crafts. The point over which the organizers of the crafts have boggled is the possibility of so organizing the unskilled as not to hurt but really to bolster up the crafts. Could the unskilled be persuaded to forego their own advancement for the present material support which the crafts must afford them?

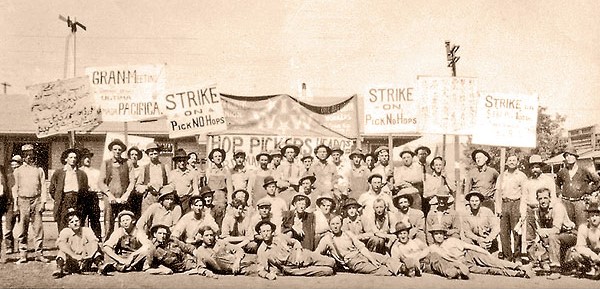

But the notion began to spread more and more rapidly among the rank and file of the crafts that, after all, they had something in common with the mass of unskilled. The proof of this is seen in the encouraging support which the A.F. of L. unions have given to the most desperate class of migratory laborers, as the hoppickers of Wheatland.

Here we get the dawning of a newer and broader idea of solidarity. It is clear, moreover, that this idea has not come from any growth of altruism among the skilled laborers but is the product of certain changes in the industrial process which tend to break down the position of the skilled workers.

The relations between the two classes of labor have been reversed in many fundamental industries. As a result of the development of machinery and the growth of the technological process the skill of the skilled has begun to lose its commanding influence. It has ceased, in certain essential industries at least, to be the basis of the labor side of production. The dominant factor ceases to be the skill of the individual worker, it becomes the discipline and coordination of the mass of workers.

The almost automatic and rhythmical regularity which marks the modern factory, the monotonous repetition of the same movements, so many to the minute, hour in and hour out, the minute subdivision of the work so as to secure a sort of uncanny dexterity, the handling of subdivided processes with a speed and accuracy which demands incessant and implacable drill, all these contributed to the change. Behind these again were the imperious needs of the market which necessitated a competitive effort to produce large amounts of goods to satisfy ordinary needs. Immense profit lies in supplying masses of men and in the control of the market for cheap goods, without refinement and possessed of no artistic qualities. This in its turn implied the falling off of skilled labor as the determining factor. Quantity and not quality becomes the essential element. The whole process of modern industry, then, and the operation of the modern markets appear to have entered into a conspiracy to dethrone the skilled craftsman, at least as the determining and necessary factor in the productive process.

That the skilled craftsman was on his last legs became apparent from the result of his strikes. The period of victory has passed. The conditions which now confronted the crafts offered an altogether unanticipated resistance. The new processes, which had at least partially eliminated skill in many crafts, of which molding, glass-blowing and printing may serve as examples, had proven successful; the numbers of the unemployed were a constant menace which rendered the result of every strike at least problematical; the ease with which the new machinery could be learned placed the unskilled almost on a level with the skilled; and the entire terrain of the fighting was thereby so changed as to make a successful campaign on the old lines actually impossible.

The directing intelligence of the labor movement however seemed to have no consciousness of all this. The old and well tried tactics were incessantly repeated. The rank and file responded as loyally as ever to the demands of the leaders. But the forward movement of the crafts was blocked. Here and there a transient gain served to conceal the general loss but on the whole the retrograde movement was marked. This necessarily affected morale and attempts were made in certain quarters to revivify the exploded theory of terrorism.

The fact that the governing class and the industrial overlords were practically identical by this time gave the controlling industrial interests the unrestricted use of the police power, which was all the more readily placed at their disposal, since the wide area of industrial strife threatened ever direr social consequences and increased the dangers of public disturbance. Where the local authorities were unable to deal with the situation and the local militia, as in the recent Colorado troubles, met with armed resistance, the advent of the Federal troops under cover of preserving order put an end to the strike.

In short the crafts ceased to be effective because their industrial background was gone. They were no longer the main factor in industry and consequently they could no longer determine the contest for industrial control. As a matter of fact they had no idea of industrial control. No such notion had ever possessed them. Their minds were incapable of grasping it. Security of employment, a fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay; a more or less complete ownership of their job, as a job; these represented the sum total of their desires and aspirations. But these aspirations, modest as they were, could not survive the destruction of the system on which they were based.

With the craftsman’s system and the craftsman’s organization there gradually also disappeared the narrow and circumscribed notion of solidarity conceived among these surroundings.

Such were the conditions antecedent to the new form of industrial action, the mass-strike. As has been pointed out, industry on the labor side became less dependent upon individual skill than upon the organization, control and discipline of masses. As a result, the mass so subjected to organization grew more and more coherent. It began to find expression as a mass, to think as a mass, to feel as a mass, and to have mass aspirations. James Thompson, the I.W.W. organizer, when describing the methods employed in teaching the idea of mass action to the textile workers at Lawrence prior to the strike, tells how the speaker held his hand up, clenched, as an illustration of the proper way to organize and then held his hand up with the fingers outspread as an illustration of the wrong way. Uneducated and inchoate as were the textile operatives they rapidly caught this idea, and, repeating the lesson to themselves, would say “This way, not that way.”

The very environment of factory life produced mass organization and the conditions of mass employment necessitated the mass strike. Henceforward the employer would not find pitted against him a more or less loosely assembled collection of labor units but an approximately compact body of employees with an approach to a mass psychology.

This has been made clear by a series of labor efforts both in the United States and Europe, put for- ward by the hitherto neglected masses of what was at the best but partially skilled labor. The capitalists, like the socialists and the labor leaders, were completely taken by surprise by these demonstrations and in the early days of these movements victories as sweeping as unexpected marked the actions of this new force. In Italy, France, Russia, Argentina and the United States the same phenomenon appeared. In occupation as widely severed as the textile industry of Lawrence and the transportation industry of Great Britain we had the same demonstrations. In some cases they were successful, in others, again, they failed. But their temporary success or failure was not the point to be observed. The principal matter was that a portion of the working class had at last arrived at the place where mass action was their natural and spontaneous expression; that that portion of the proletariat which had hitherto been considered incapable of organization had consciously striven for a new and effective form of organizations which transcended all its predecessors in its scope and potentialities.

Not only in the sphere of what is ordinarily termed industry, but, more unexpectedly, in agriculture we find the same phenomenon. In Italy the agricultural laborers of the South under very discouraging conditions not only made successful strikes but wonderful to say carried on successful mass cooperation. Their cooperative farming has won a place among the achievements of the international proletariat, where even their warmest sympathizers had hardly anticipated success.

In the United States particularly in the Pacific Coast States where the agricultural conditions necessitate the employment of seasonable labor, we find the unskilled migratory laborer, who is, generally and not without reason, regarded as the least hopeful of workers, actually undertaking to organize himself. After one sharp conflict in the State of California, he compelled the state government to recognize his demands for decent camp conditions and brought about a change in that respect which was little short of revolutionary.

In short the new movement was a mass action movement produced by the mass conditions of employment. It sprang directly from the conditions, which indeed it mirrored. It was not the work of agitators, it was based on no philosophical teachings, though it, naturally and inevitably, developed a philosophy suited to itself, and its own peculiar origin. The basis of this philosophy on the ethical side at least was the rather over-worked word “solidarity.” Of course under such conditions “solidarity” meant something vitally different from what it had hitherto implied. As the working class organization was broader and as mass-organization implied something much more extensive than the mind of the average trade unionist could grasp, the solidarity preached by the new organization was much more inclusive and definite. Instead of reflecting the ideas of a limited class of skilled men, it began to reflect the common desires of large numbers of average men. It was inclusive rather than exclusive. Different from the old trade unions, again, it began to include women and children in its scope. Much was made of the proclamation at Lawrence that the industrial union was for women and children as well as for men.

This new point of view however was not acceptable to the old craft unions. It met with the most vehement opposition in England and America, as elsewhere. In New Zealand an attempt at mass organization of transport workers was violently assailed by the established unions. Various attempts were made to control the new movement by the older unions. In Germany this brought about a struggle in the Congress of German Labor Unions in 1914.

In this last instance the old unions demanded the entrance of helpless and unskilled workers into the trade and industrial unions to which they were eligible. This demand was indicative of the determination of the old unions to control the new labor movement and parallelled the requirements of the Building Trades in the United States that the United Laborers union should affiliate with them.

The factory workers on their part demanded the entrance of skilled workers into the unions of the unskilled to which they were eligible. On this matter the New Review (Aug. 1914) says:

“The resolution was defeated and the executive committee’s recommendation of an arbitration court was adopted. The factory workers made a statement reaffirming their claims to the skilled workers in establishments under their control and called the proposed court a ‘compulsory arbitration court.

“While the factory workers were defeated by 2,210,000 to 309,000 votes, the transport workers also showed themselves decidedly oppositional. The unskilled opposition, however, is, for the most part, within the great German unions themselves. For there the Metal Workers, Wood Workers, Building Workers, etc., instead of being divided into a number of loosely federated unions are united into single groups. And since the skilled workers are largely organized and the unskilled largely unorganized, the latter are usually in a minority. Yet there has been a great deal of friction of late, especially in the greatest union of all, that of the Metal Workers, which has over half a million members.”

It is clear that here we have the beginning of a new conflict which must continue until the structure of organized labor is profoundly modified. The change in the industrial basis involves necessarily a corresponding change in the labor organization. This is already becoming sufficiently recognized to cause an agitation in favor of industrial unionism even among the rank and file of the old craft unions. Such changes as are contemplated by these will not however meet the situation, for the mind of the masses is already prepared for some attempt at an organization on a vastly more comprehensive scale, than is implied in the term industrial unionism as understood by the American Federation of Labor.

The revolutionary changes which have destroyed the crafts man’s position have also destroyed the craftsman’s ideals. The old individualistic concepts of the skilled worker are gone. Henceforth the worker is compelled to think in terms of the mass, compelled by the very force of circumstance and environment, which shape his thoughts and ideals whether he will or not.

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of full issue 1: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1915/v3n18-dec-01-1915.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1915/v3n19-dec-15-1915.pdf