‘The Cold Wave and the Workers’ by Elias Tobenkin from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 12 No. 8. February, 1912.

NEW YEARS morning, 1912, the capitalist press of New York devoted column after column to interviews with senators, governors, bankers and captains of industry in which these men of eminence assured the public that the year 1912 would “continue the record of prosperity” with which the country was “blessed” in 1911.

Governor Dix telegraphed the New York World that “the New Year finds the Empire State solvent, prosperous and serenely confident.”

These optimistic statesmen had evidently not taken the weather into consideration when they talked so eloquently about the “record of prosperity.”

Five days after these interviews appeared New York was in the grip of a cold wave. And the same capitalist press suddenly discovered not only that New York has poor who suffer during the cold weather, but that the Empire City of the Empire State actually has thousands of homeless unemployed men and women walking the streets in summer clothing, and some in rags, penniless, hungry, many doomed to death from exposure, if the city does not bestir itself and rise to the situation.

The same newspapers that five days previous were so “serenely confident” now opened their columns to frantic appeals by the heads of charitable organizations for “anything that you can give,” an old coat, an old pair of trousers, socks, old shoes, and even discarded underwear. All of these things, the charity heads assured the public, would be welcomed by thousands of men who were in want of them.

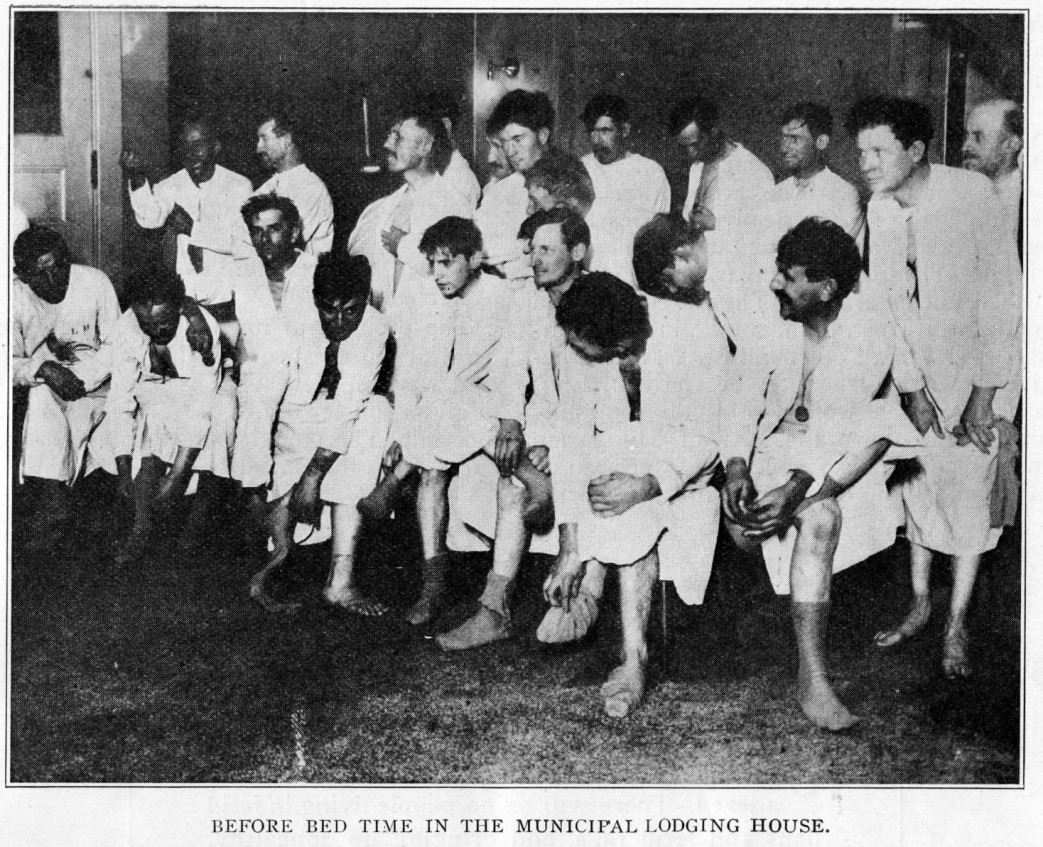

Friday night, January 5, the municipal lodging house of New York broke all of its previous records. It housed 977 men, though it had room only for 738. To accommodate the remaining few hundreds, men for whom there was no room in the municipal lodging house, the morgue was resorted to. The chapel of the morgue was thrown open and packed with half-frozen humanity, who spent the night huddled together on benches, and divided only by a thin wall from the vaults containing the usual quota of unidentified dead, that are also drawn from the ranks of these unemployed.

The Bowery Mission, which conducts the “bread line,” fed more people than ever before after midnight that night. But the climax of the tragedy and suffering of the half-naked and half-starved men and women of the metropolis was reached Saturday afternoon.

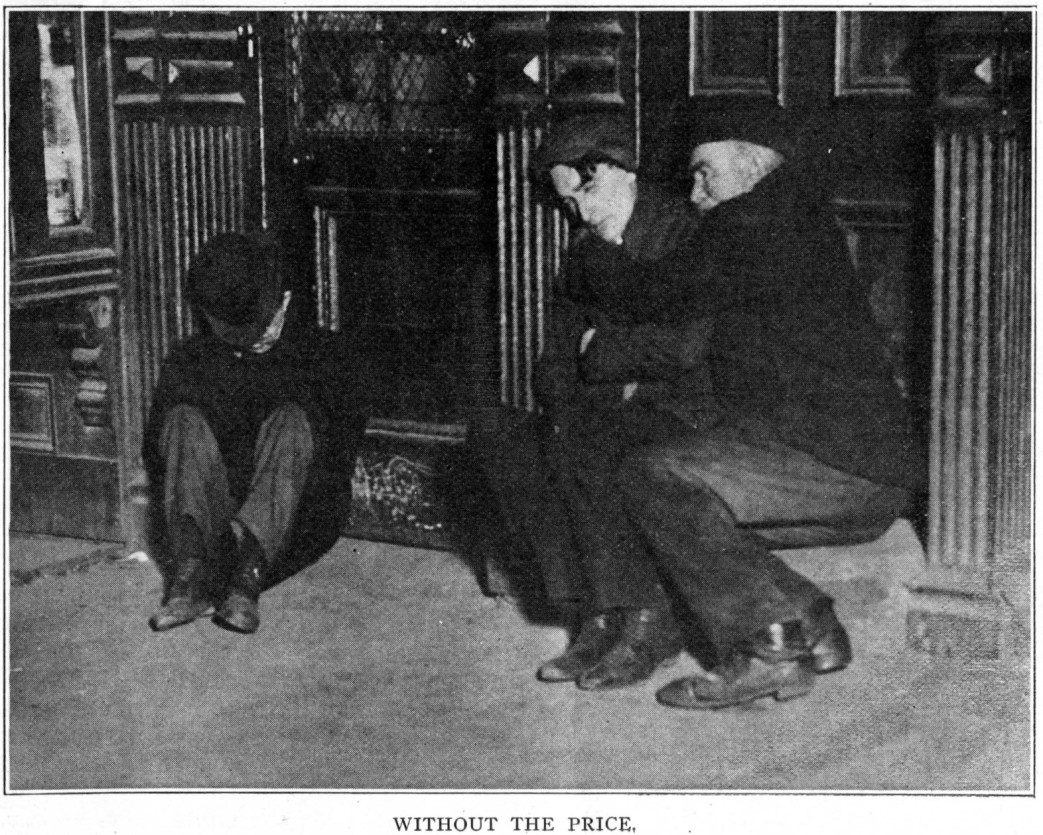

All day Saturday the thousands of homeless men, who ordinarily keep on walking the streets, sought the saloons, but having no money to spend there would find themselves shoved out of the barroom by men who were a nickel the richer and could afford, therefore, to buy a glass of beer and the privilege of sitting and dozing before that glass of beer for hours.

The reading room of Cooper Union, a favorite resort with the more intelligent of the unemployed, was packed to its utmost capacity. Even the halls of Cooper Union were packed with freezing humanity. A bit of standing room near a radiator was at a premium.

Driven from the saloons for want of a nickel, hundreds of ragged, shivering individuals would march up to the post office and walk through the lobby. Here, however, watchmen are on the look out for that class of visitors, and “loitering” is not permitted. Here and there a man would try to get around the watchmen by scribbling something on a piece of paper and pretending that he was writing a letter.

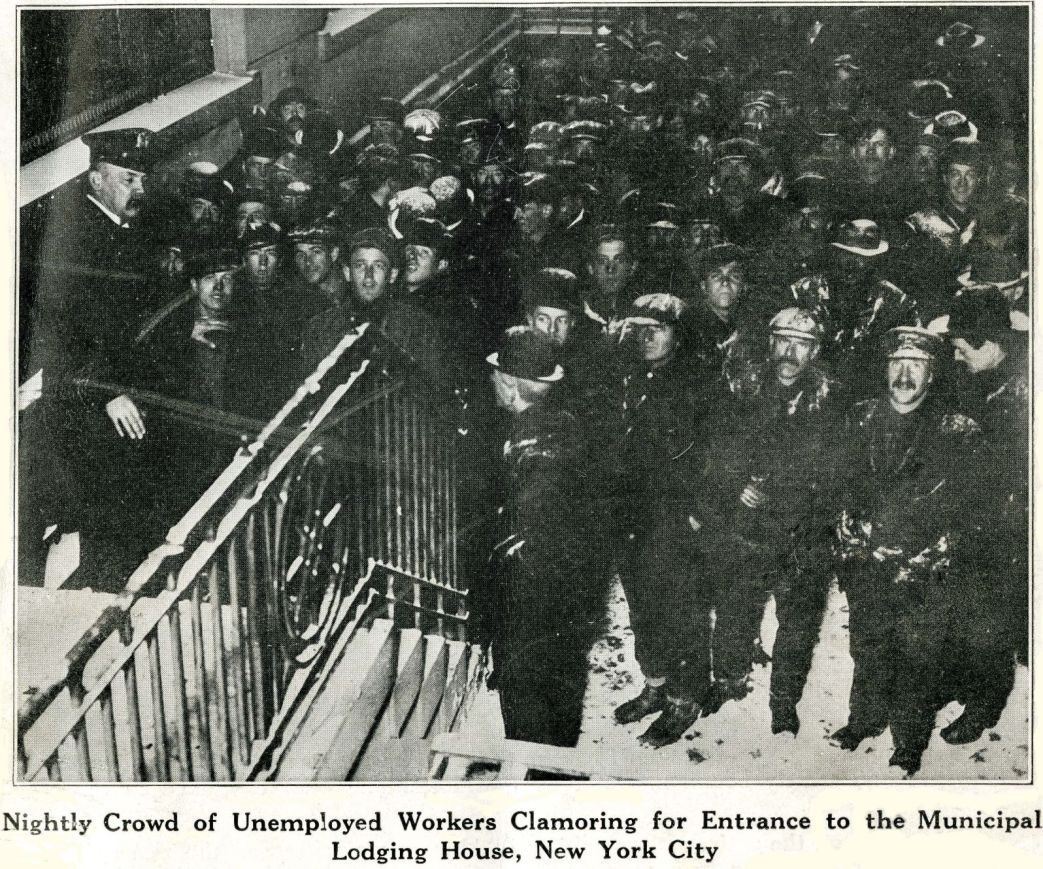

At 4 o’clock in the afternoon the situation changed. There was an exodus from saloons, from Cooper Union, from the lobby of the post office and from a hundred other places haunted by the unemployed. All started in the direction of the municipal lodging house. At 5 o’clock the sidewalk in front of the lodging house was jammed with hundreds of shivering, overcoatless men and: boys. Here one could: examine them carefully. Most of them wore what were once summer suits. Their shoes were torn. Their trousers, clinging tightly to their legs, when a gust of wind hit them, indicated that they wore no underwear, or at least no winter underwear. Many of them wore no stockings of any kind.

By 5:30 o’clock the army of these men and boys swelled to about 500. The wind from the river lashed against their faces until they looked as if they had been knouted, and that the blood would spurt out of their cheeks in a moment. Their eyes became red, their eyelids swollen.

The rule in the municipal lodging house is that the doors are not to be opened before 6 o’clock. But when Superintendent William C. Yorke looked out of the window at 5:30 and surveyed the crowd, his otherwise placid face was moved, and he ordered that the doors be opened at once.

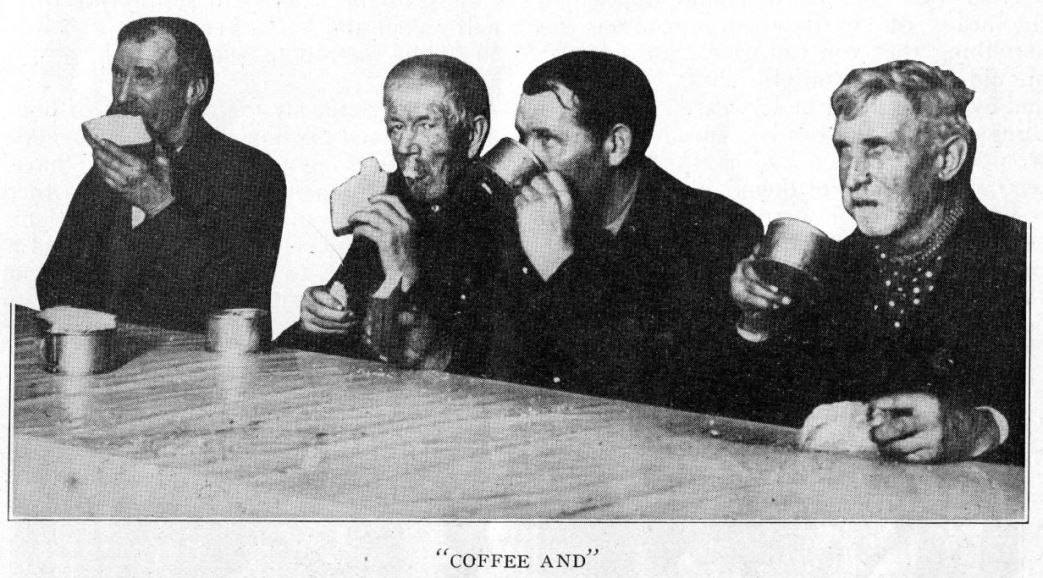

From 5:30 o’clock until 10 in the evening three men were busy taking the pedigrees of these homeless men and boys. After they were “registered” they were sent up for their cup of coffee and bread. Then came the bath and the inspection by the doctor. More than a hundred had frozen fingers and toes. A few were taken to the Bellevue Hospital suffering from exposure.

Before 8 o’clock every one of the 738 beds in the lodging house was occupied. Some 300 people were still on the floor, waiting to be given a place to sleep. Others were straggling in from the outside. The superintendent ordered that the waiting rooms of the municipal dock, which had been heated that afternoon, be thrown open to these men, In a few minutes the waiting rooms were jammed full of people. Here the men could not even lie down. The benches in the place were of the park variety, providing seats for four men to a bench. They were to sit this way through the night. But the men were glad to get even that.

After every available room on the dock had been used up, there were still hundreds of men who had not been provided for. They could not be turned out into the street. The morgue chapel would not hold them all. Besides, the superintendent of the Municipal Lodging House would not risk having the papers state again that the unemployed were “put in the morgue,” as even the capitalist newspapers stated in their headlines. So a steamboat, used by the city for transporting criminals to Blackwell’s Island, was hastily heated and put ‘in operation. And hundreds of men for whom New York City had no room on terra firma were consigned to the boat to spend the night there.

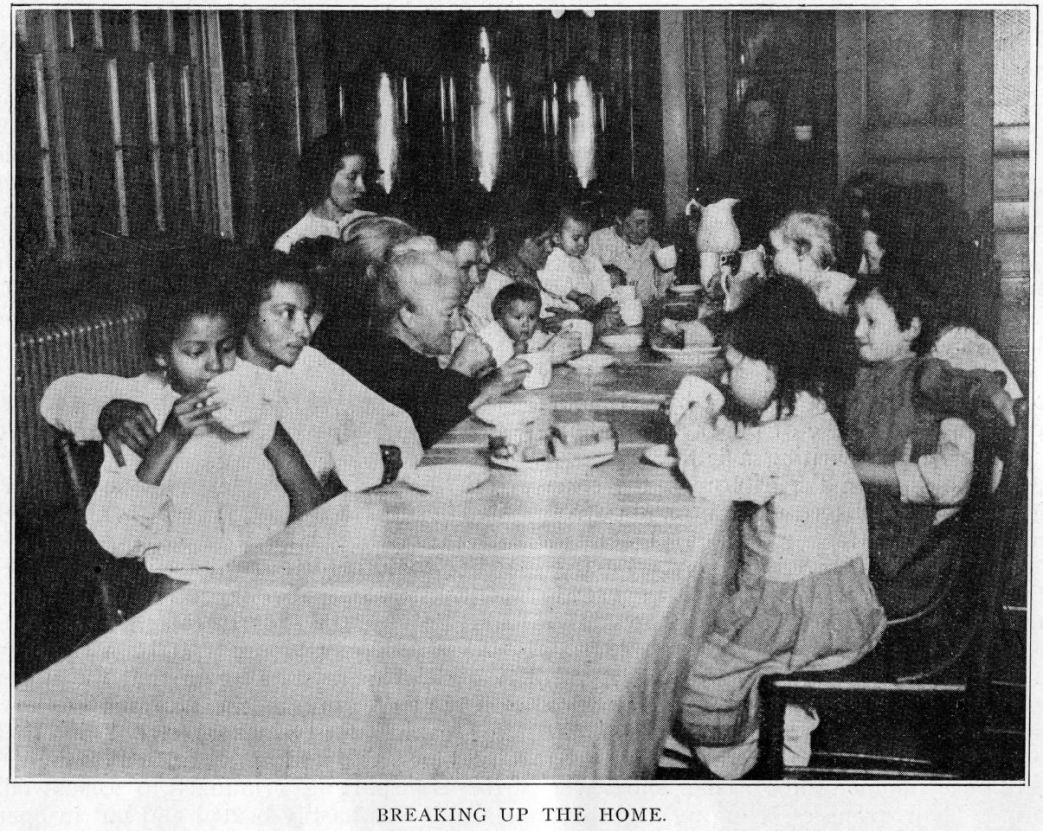

The homeless, unemployed man is a common sight in New York. He no longer excites comment. Not so with women. One seldom sees a woman out of work and penniless. A woman can do washing, scrubbing, and earn a quarter this way. She can get a nook in some restaurant kitchen to lay her body down for the night in return for washing dishes. “But there were 24 women in New York on the night of Saturday, January 6, 1912, who absolutely had no place to lay their heads. And there were five children who were likewise homeless because their mothers were jobless. These 24 mothers and five children were housed in one of the dormitories in the municipal lodging house.

The ages of the five children ranged as follows: A babe three weeks old; a little girl two years old, another little girl two and a half years old, a boy five years old, and another boy, eleven.

About 9 o’clock, when the rush at the municipal lodging house was beginning to subside, when nearly a thousand men had already had their cup of coffee and two slices of bread, and had been sent down toa take their bath, get a physical examination by the doctor in attendance, and be consigned to their beds, Superintendent Yorke was buttonholed by the reporters and asked for facts and figures concerning these men.

Here are some the figures that were given the reporters by Mr. Yorke at that hour:

A little over 1,000 men had been registered. Of these, fully 70 per cent were overcoatless. Fifty per cent had no underwear or stockings of any kind. Twenty per cent had light summer underwear on.

“If you want to do a charitable deed,” the superintendent told the reporters, “state in your papers the condition of these men, that they are half naked. Any piece of clothing that any citizen can spare will be appreciated by us and he will be blessed by some unfortunate youth or man who is half naked in this bitter cold.”

One of the functions of a reporter is “to fix the blame.” When an accident occurs in which lives are lost the reporter assigned to the story is told to try and fix the blame, to try and find out who is responsible for the accident.

This function of “fixing the blame” extends to many other things. For example, many a well meaning citizen would be greatly relieved if, upon reading in the newspaper the story of the suffering of the homeless, naked and starved men who were crowding the municipal lodging house on that cold night, could find a paragraph explaining that the men themselves were really to blame for their condition; that if they had been frugal, had saved money when they were working, or had been willing to take work even now, they would not have been in such a plight; they, too, could have had homes.

It was with a view of being able to insert just such a paragraph blaming these unemployed men for their unemployment that one reporter asked:

“Are there any hold-up men among them? Any strong-arm men, any panhandlers?”

Now, Superintendent Yorke is not a Socialist, at least not so that you can notice it. But he looked at the reporter with a semi contemptuous smile.

“Go over and take a look at the men,” he said, “see if they are the kind of men from whom strong-arm men, hold-up men and panhandlers are recruited. The class of men you refer to do not come to the municipal lodging house. They can afford to pay for their rooms.”

“These men,” the superintendent went on, “are all mechanics, and laborers. They are anxious to work at anything. I have had hundreds of them come to me today, each asking if I could not give them a job working around the lodging house. I have never seen such a respectable crowd of men before in all my life. Look at the faces of some of them, and you will recognize men of refinement among them. Did you see how neat some of them tried to keep themselves? It is astounding how many people there are in New York who cannot find work.”

Not a word of these remarks of the superintendent really “fixing the blame” for the condition of these men appeared in the newspapers the next day, though columns were printed about how the charity institutions responded nobly and came to the assistance of the poor and unfortunate.

Other figures given by the superintendent ‘fixed the blame” even more definitely. In 1910, he said, the municipal lodging house of New York broke the record for all years past in the number of persons it housed. But even this “record-breaking” period of 1910 was broken in 1911, when the municipal lodging house gave shelter to 51,000 more people in 1911 than in 1910, The total number of people sheltered in 1911 was 167,800. When one remembers that the municipal lodging house is hot on the trail of every man who is “not deserving,’ who is a professional tramp, etc., one can form a conception about the extent of homelessness and unemployment in New York and in the United States.

A remarkable, though easily explained, feature is the fact that the men applying for shelter at the municipal lodging house are nearly all classed as natives—that is, American born. According to nationality they range as follows: American, Irish, German, English, Scotch. The Slavic races, Austrians, Hungarians and Jews, furnish the smallest number of municipal lodging house candidates. The explanation for it is simply this: American industries today need brawn, and brawn that will work cheap. The Slavs, Hungarians, Jews furnished cheap brawn. They are preferred by the steel trust, in the mines, in the sweatshops, and in all other industries, to the native American labor, to the German, English or Scotch workman. You can bully and thumb down the Slav or Hungarian more readily than you can the American or German. You can house the Hungarian or Croatian or Italian in a shanty with much less compunction than you could an American.

Hence the American is, by a sort of tacit agreement of all industrial captains, relegated to the ranks of unemployed, while the immigrant, who willingly or unwillingly submits to lower wages, a lower standard of living, to inhuman, beastly treatment, is preferred.

The problem of unemployment has been growing in this country for years. The cold wave in New York is now showing it in all its sinister ugliness. The jobless man bids fair to become the most acute economic and social problem in the next two or three years in the United States.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and loyal to the Socialist Party of America. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v12n08-feb-1912-ISR.riaz-ocr.pdf