‘The Origin of the Word ‘Boycott’’ from The Worker (New York). Vol. 5 No. 29. October 14, 1905.

In his “Talks About Ireland”, James Redpath describes his visit to Ireland in 1880. Mr. Redpath says that there was a fierce spirit brooding among Irishmen and that if some bloodless but pitiless policy was not advocated there would soon be killing of landlords and land agents all over the west of Ireland. Being called upon for a speech at the village of Deenane, in Connemara, he addressed the tenants, whom American charity had kept alive since the preceding autumn, as follows:

Well, now, let me talk very plainly about two tender topics. I honor every man who sheds his blood for his country or who is willing to do it. But there is no need of bloodshed. You can get all your rights without violence.

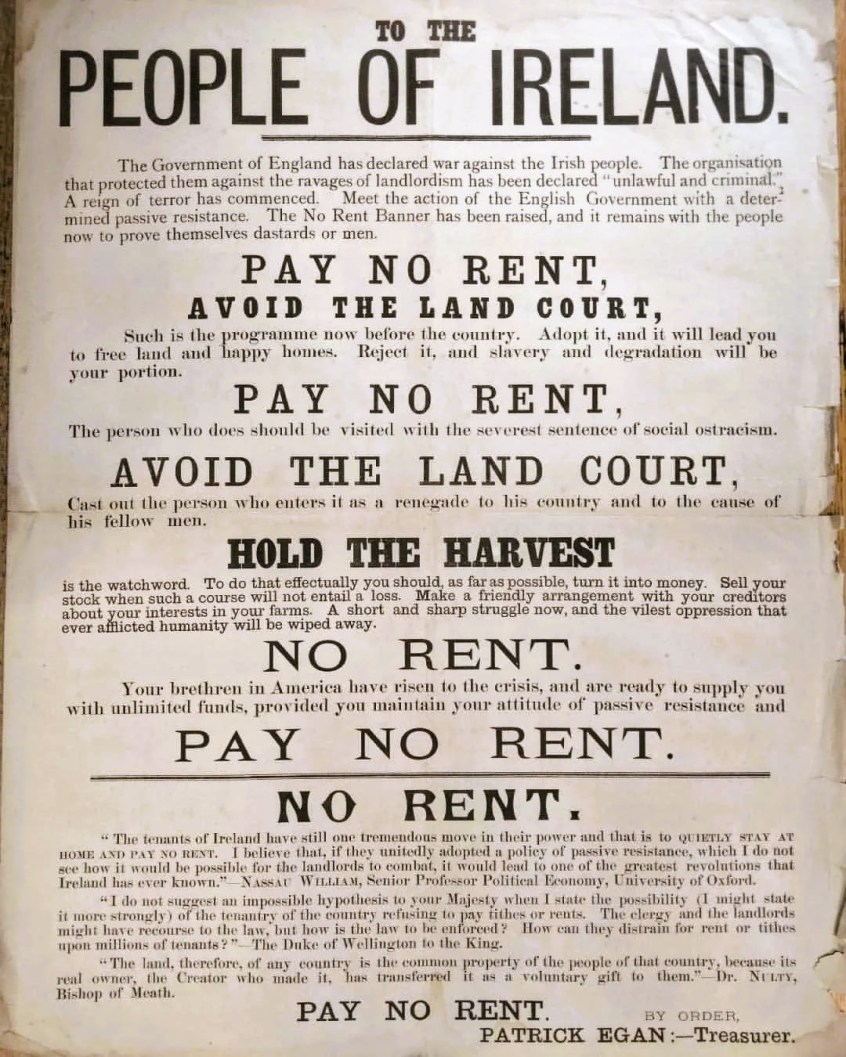

Call up the terrible power of social excommunication. If any man is evicted from his holding, let no man take it. If any man is mean enough to take it, don’t shoot him, but treat him with scorn and silence. Let no man or woman talk to him or to his wife or children. If his children appear in the streets don’t let your children speak to them. If they go to school, take your children away. If the man goes to buy goods in a shop, tell the shopkeeper that if he deals with him you will never trade with him again. If the man or his folks go to church, leave as they enter. If ever death comes, let the man dies unattended, save by the priest, and let him be buried unpitied. The sooner such men die the better for Ireland. If the landlord takes the land for himself let no man work for him. Let his potatoes remain undug. his grass uncut, his crop wither in the field. This dreadful power, more potent than Armies, the power of social excommunication, has been most used in our time by despots in the interest of despotism. Use it, you, for justice! No man can stand up against it except heroes–and heroes don’t take the land from which a man has been evicted. In such a war the only hope of success is to wage it without a blow–but without pity.

You must act as one man. Bayonets shrivel up like dry grass in presence of a people that will neither fight them nor submit to tyranny.

This was the thing. Now let us see how the name arose. We quote again:

Captain Boycott had won for himself the reputation of being the worst land agent in the County of Mayo. In addition to charging exorbitant rents, he compelled the tenants of the landlords for whom he was agent to work for him on his own farm at his own rates, so that they never actually received more than a dollar and seventy-five cents a week.

The land agitation suddenly aroused the tenantry to a sense of their power, which they could wield without violating any law, if they would combine and act as one man. The first use of this power against Boycott was made when he sent last summer for the tenantry of the estates for which he was agent to cut the oats on his own farm. The whole neighborhood declined to work for him. The willful old fellow swore he would not be dictated to; he had always dictated to them. So he and his nephews and his nieces and three servant girls and herdsmen went down to the fields and began to reap and bind. He held out three hours, but could not stand it longer.

Mrs. Boycott went from cabin to cabin that night to coax the people to come and work for her husband at their own very moderate terms.

They came.

When rent day came Boycott sent for the tenants. His day of vengeance had dawned, as he thought, but it proved his day of doom.

Boycott issued the eviction papers and hired a process server and got eighteen constables to protect him.

Next morning when Mrs. Boycott went to buy bread the shopkeeper told her that altho she was a decent woman and they all liked her, yet the people couldn’t stand that “baste of a husband of hers any longer,” and they really couldn’t sell her any more bread.

Boycott was isolated. He had to take care of his own cattle. His farm was of 400 acres.

Boycott wrote to the “Times”, and the English landlords organised a relief expedition: fifty men were hired and seven regiments of soldiers were sent to protect them. It cost the British government $5,000 to dig $500 worth of potatoes.

The term “Boycott” was invented three days afterward by Father John O’Malley, who used it in the Castlebar “Telegraph”.

The young orators of the land league in Dublin took up the word and it became famous at once.

This was not, of course, the first case in history in which the method now known as the boycott, the most terrible and yet the least cruel of weapons, was used. The great instance in its early history is when the American colonists, in the years preceding 1776, “boycotted” imported goods on which. the British government imposed taxes without their consent. If anyone says the boycott is “Unamerican”, we can tell him that John and Samuel Adams and John Hancock and Patrick Henry were among the first boycotters. And if the objector happens to be an Irishman–Irishmen in this country are the most aggressive of Americans–we can tell him that the word was born in the struggles of his countrymen against British landlordism.

The Worker, and its predecessor The People, emerged from the 1899 split in the Socialist Labor Party of America led by Henry Slobodin and Morris Hillquit, who published their own edition of the SLP’s paper in Springfield, Massachusetts. Their ‘The People’ had the same banner, format, and numbering as their rival De Leon’s. The new group emerged as the Social Democratic Party and with a Chicago group of the same name these two Social Democratic Parties would become the Socialist Party of America at a 1901 conference. That same year the paper’s name was changed from The People to The Worker with publishing moved to New York City. The Worker continued as a weekly until December 1908 when it was folded into the socialist daily, The New York Call.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-the-worker/051014-worker-v15n29-electionspecial.pdf