William D. Haywood often told stories from his vast working-class experiences to illuminate points, entice empathy, or put his audience at familiar ease. Here is an example; a ‘dope-fiend’ named McCann in Silver City, Idaho who refused to name names despite the torture of withdrawal and threat of the penitentiary.

‘Loyalty (An American Story)’ by William D. Haywood from the Daily Worker Saturday Supplement. Vol. 1 No. 323. January 26, 1924.

Everything was in full swing in the corner saloon when I dropped in one night in the Winter of ’99. The billiard, pool and gambling tables were all running. A roulette wheel, a faro-bank and two stud poker games were crowded with players.

Calling up the stragglers to have a drink, I said to Ben Hastings, the bar-keeper, “Who is the man in the corner chair, The man sat huddled up with his hat drawn down over his face. Ben replied, “That is old McCann; he don’t drink much but he would sell his soul for a dose of morphine.”

I beckoned to him; he came strolling up, shoving his hat back a little. He said, “I guess you don’t remember me, Bill, I used to know you in Tuscarora.” I recognized him, tho the few intervening years had made much change in his face and physique. He was now emaciated with the ravages of the drug. His eyes were unusually bright, but shone out of deep hollows. His face was gaunt and sallow. There was a nervousness about him.

I walked over to the faro layout, put a silver dollar behind the ten-spot, playing the nine and pack open. I won on the turn. “Silver,” I said to the dealer. Picking up the coin I went back to the bar, and bought another round of drinks. As I was leaving I saw one of the miners who was working with me on the Trade Dollar Mine talking confidently to McCann, the dope-fiend.

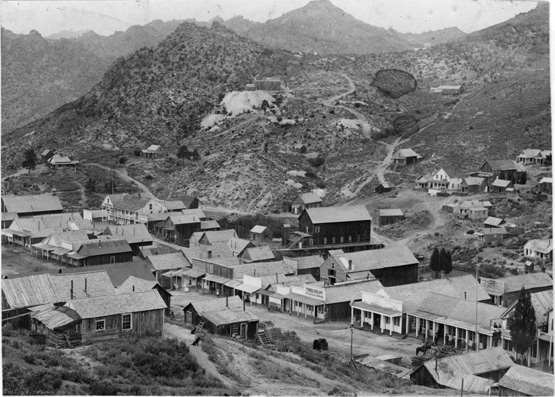

Nearly every mining camp has its corner saloon. The one I mention here was located in Silver City, Idaho. A little town built in a narrow gulch between Florida and War Eagle Mountains. These towering peaks stood as mighty guards over the bustling little burg with its foundation in the bed of the stream that had been turned bottom side up by the gold diggers of the early ‘sixties. It was typical of many mining camps of the West. The saloons and other less important business houses were on the principal of the two streets of the town. The red light district occupied the rear street, populated by white, black and Chinese women.

Cabins and little houses, the homes of the married miners, were scattered about the surrounding mountain sides. The snow fell deep that winter and there was little to mark their locality except the stove pipes and an occasional chimney, sticking up thru the snow.

The following morning as I was going to work I passed McCann’s Potosi Gulch. A light was shining thru the window.

That morning the old dope-fiend was arrested at the stage office. He had gone early with a box to be shipped to Salt Lake City. The Sheriff was waiting for him. Took both him and the box to jail, where upon examination the box was found to contain high-grade ore, that would run several dollars to the pound.

McCann was locked up charged with grand larceny. A scoundrel, nicknamed Tamarack, whom he had sheltered in his cabin, had squealed on him. Mac was facing a serious situation. Conviction would mean a long term in the penitentiary. This chase of the dilemma did not worry him. He was thinking of the tortures he knew he would suffer if deprived of the drug that for years had made life endurable for him.

About mid-day the Sheriff came to the cell-door, saying “Well Mac, how are you?” With trembling voice, “I’m a little shaky, must have some medicine. On account of my nerves I have taken morphine pretty regularly. You know one who has used as much of it as I cannot get along without it. You can get it at the drug store next to the post-office. Tell him its for me, he knows what I’ll need for the night. You’ll do that for me won’t you sheriff?” “Sure, sure, I know your condition.

By the way, Mac you know the Mining Company have no intention of cinching you. But we’ve got to have the names of the men who gave you the ore. The stealing of rich specimens has been going on for a long time. We’ll put a stop to it now. Who are the fellows?” Mac looked the sheriff square in the eye “I cannot tell you,’ was his answer. The sheriff turned and walked away saying, “Alright, I’ll see you later.” It was growing dark. Mac’s every nerve was vibrating. His brain was hot.

He trembled as with the ague. He knocked on the grated door with the tin cup. The sheriff came. Mac said, “Did you get that stuff for me?” “No, I’ve been busy.” But, encouragingly, “I will before the store closes. You know the names of those men, do you Mac?” “Of course I do,” came the response in a shivering tone. “I thought you did,” the sheriff remarked. “I’ll get the morphine for you to-night.”

The hours and minutes dragged and thumped. Mac paced the cell, now and then steadying himself against the wall. With all his force he tried to quiet the pangs of brain and nerve. The sheriff’s promise gave him strength to fight against insanity and what he thought was approaching death. At some monstrous visions he screamed out in agony, and so wore the night away without a wink of sleep.

Morning found Mac clinging to the bars. His face white, his body limp. The guard came with his breakfast. Mac braced himself to say, “You get me some. You can get it.” The guard with a laugh said, “You’ll have to wait till the sheriff comes; I can’t leave here anymore than you can.”

The sheriff came late. Mac was still leaning against the grated wall, the food untouched in the pan on the floor. “Well, Mac, how are you?” Startled by the voice, he straightened up, staggered back, tripped on the food pan, slipped and fell. He dragged himself to the door, pulling himself first to his knees and then to his feet. Putting a scrawny, scarred arm thru the bars, he groaned, “Give it to me, give it to me. God! Sheriff, I’m dying.” The sheriff pulled the short blue bottle from his pocket. The white narcotic filled it to the cork. Spasmodically, Mac’s shrivelled hand clawed for what he knew was surcease from his terrible agony. Mentally and physically, he had already nearly collapsed. The sheriff smiled, “Don’t be in a hurry Mac, you’ll get it. You never wanted the stuff so bad before, did you?” Mac’s eyes were filmed. His face was ashen white. The fingers on his bare arm that protruded thru the bars opened and closed nervously. “Give me a little. Just enough to ease my head, I’ll go mad.” “You can have it Mac; but I must know the men who gave you the ore.” Mac did not raise his head, but said, “You can kill me, but I cannot tell you. It is their wives and children that I am thinking of.” He pulled back his hand. The grip of the other relaxed, and he sank in a miserable heap on the floor.

The company doctor was called, resuscitated Mac with a little brandy, but was deaf to his pleadings, and would give him none of the narcotic. The vile craving was gnawing viciously at every fibre and tissue of Mac’s body. His brain squirmed, his skin creeped. Death would be his certain release, but it would not come. There seemed to be nothing but torment, torture aggravated by the sheriff with the little blue bottle.

A few days later they led Mac into the court room more dead than alive. The prosecuting attorney asked him who the men were that were involved with him in the theft of the ore. He muttered, “I cannot tell you.”

Mac was found guilty of grand larceny. Sentenced to seven years of hard labor in the Boise Penitentiary. He died there while serving his time. They said he would sell his soul for a dose of morphine, but he stood the tortures of the damned, and sacrificed years of his life for–loyalty.

The Saturday Supplement, later changed to a Sunday Supplement, of the Daily Worker was a place for longer articles with debate, international focus, literature, and documents presented. The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1924/v01-n323-supplement-jan-26-1924-DW-LOC.pdf