Union iron-molder and working class journalist offers another example of the Review’s reporting on changing technologies and its myriad effects on labor with this look at the hellish coke industry. Coke might be thought of as distilled coal, a necessary ingredient in iron smelting, and therefore a cornerstone of modern industry. Kennedy describes the changing process in brutal detail.

‘Revolution in the Coke Industry’ by Thomas F. Kennedy from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 11 No. 11. May 1911.

COKING drives off the gases in coal without burning up the carbon. During the last three years a revolution has been under way in the coke industry. It is not the work of pestiferous labor agitators nor of wicked trust promoters, but of machines.

Up until the advent of the by-product coking process and the machine, coke ovens were built about the shape of a beehive, hence the name, beehive oven. At first they were very small, and as late as twenty years ago ovens were built eight feet in diameter. But the size was gradually increased until nearly all of the lately built beehive ovens are over twelve feet in diameter, twelve and one-half being a common size.

Coke ovens are built in rows, the spaces being filled so that the front presents the appearance of a solid wall of masonry with arched doors about every sixteen feet. Excepting for the small, round charging hole in each oven the top is level and carries a track upon which runs the charging car from the coal tipple.

In nearly all old-time coke plants the ovens were built against a hill or rise in the ground. This was to economize heat and give solidity to the ovens. But modern practice is to build two rows back to back. This gives solidity and conserves heat even better than by the old plan.

When a batch of cold ovens, new or old, are to be started, or “fired,” as they say around the coke works, fire is kept burning in them for several days, until the walls of the ovens are hot enough to ignite coal. After being charged, the first thing is to “level.” This leveling is done by hand with a big, heavy scraper and the “leveler” just pushes and pulls until the coal is level in the oven. The hot walls of the oven ignite the coal and often within an hour, especially if the oven is charged soon after being drawn, smoke will begin to come out of the charging hole, and in seven or eight hours, a big flame. A never-to-be-forgotten sight is three or four hundred ovens on a dark night, each one vomiting a column of flame, while over them hovers a canopy of smoke like a great black pall.

When the coking is complete, the coal has become a solid, nearly white hot cake, about sixteen inches thick and the diameter of the oven. The first step is to water the oven until the hot cake is black on top and only a very dark, cherry red toward the bottom. The chief reason for cooling the coke is to prevent it from burning to ashes, which it would do if drawn out in the air while white hot; but incidentally the cooling makes it easier for the drawer to stand up in front of the oven and causes cracks in the cake, making it possible to tear it asunder.

This, still red hot, cake of coke sixteen inches or more thick and twelve feet or more in diameter, is attacked by the drawer with bar, hook and scraper as he stands in front of the oven. His hook is his chief reliance, and he has several of varying length, the shortest for near the door and the longest for the back end of the oven. The handle of the hook is of round steel with a link shaped ring at the end. The business end of the hook is of rectangular steel five-eighths of an inch thick, one and a quarter inches wide, about eight inches long, perfectly straight, turned at a right angle to the handle and sharp at the end.

He bounces his hook seeking a hold, and when he gets a “bite” he jerks with all his might until he tears the piece loose and draws it into the big, heavy iron wheelbarrow which stands directly under the oven door. When the barrow is full, it must be wheeled to the railroad car across the yard or on to the stock pile, if for any reason there should be stocking.

The bed of coke must be quarried, but the quarryman works at a terrible disadvantage. He must keep at a distance from his red hot quarry, the distance increasing until at the last he is fourteen” or fifteen feet away. Yet he cannot keep far enough from the oven to escape the stream of heat, dust, steam and sulphurous fumes pouring out of the oven into his face.

Three to four hours, according to his strength and his luck, hard tugging in front of the oven will finish the job, for which he receives about $1. Two ovens are a hard day’s work, though two one day and three the next, fifteen a week, is a regular thing. There have been exceptional cases where strong, two-legged mules pulled four a day—for awhile. As might be expected, they are terrible drinkers.

Company doctors point to the good health enjoyed by the coke drawers. The fact is that unless one has the strength of a horse and a constitution like iron he would never get the first oven pulled. No physical examination that could be devised could select the strongest and toughest as surely as they are selected by the coke puller’s hook.

Three types of coke drawing machines are developing. Two of these are designed to draw coke out of the standard beehive oven. Because of the large volume of flame and heat retained and the thorough combustion of the gases, the beehive shape is by many coke men considered the best coker, hence the efforts to adapt machines to it. Another reason is that these machines can be used at existing beehive plants with no alteration in the ovens.

One of these beehive machines consists of a steel spade fixed to the end of a piston moved back and forth by gears. Near the end of the spade is a knuckle on the same principle as the barb of a fish hook. The spade is forced between the coke and the bottom of the oven for some distance and then withdrawn, bringing with it all coke which got over the knuckle. This machine has been declared a success and is in use every day at several big works.

The other beehive machine works on the same principle as the man with the hook, tearing and clawing the coke from the top the same as the hand-drawer.

For the hitherto laborious work of leveling beehive ovens there has been devised a machine that looks something like a big steel umbrella. It is mounted on a car running on the same track that carries the charging lorry. As soon as an oven is charged it is run up and the folded umbrella let down into the oven through the small charging hole on top. As soon as it is down the umbrella opened and made to revolve by means of an electric motor, and the ribs of the umbrella acting as sweeps, quickly and perfectly level the oven. The umbrella is refolded, withdrawn and the car run out of the way until another oven is charged.

But the machine which is revolutionizing the coke industry cannot be used with a beehive oven. It must have a specially constructed rectangular oven. Plants of this type are known as “push ovens,” because the distinguishing characteristic of this type is that it pushes the coke out of the oven, and the same machine levels the oven.

At the best “push” plant I visited, the ovens were five feet wide and thirty-two feet long, giving about twenty per cent more floor area than the largest practicable beehive oven. These rectangular ovens for the “push” machine are open their full width at both ends and provided with double doors lined with fire brick. The beehive door is always built by hand after each “draw.”

The coking process is essentially a roasting process and goes on in very much the same manner that a joint of meat roasts in your stove oven. The object of coking is to drive off the gases without consuming the carbon. The beehive shape gives the space for the thorough combustion of the gases and the accumulation of a large body of flame and heat. So the rectangular oven imitates as nearly as possible the shape of the beehive, and instead of a straight arch like a tunnel or sewer, it rises from each door toward the center at an angle of about forty degrees, which gives ample room for combustion and the accumulation of heat.

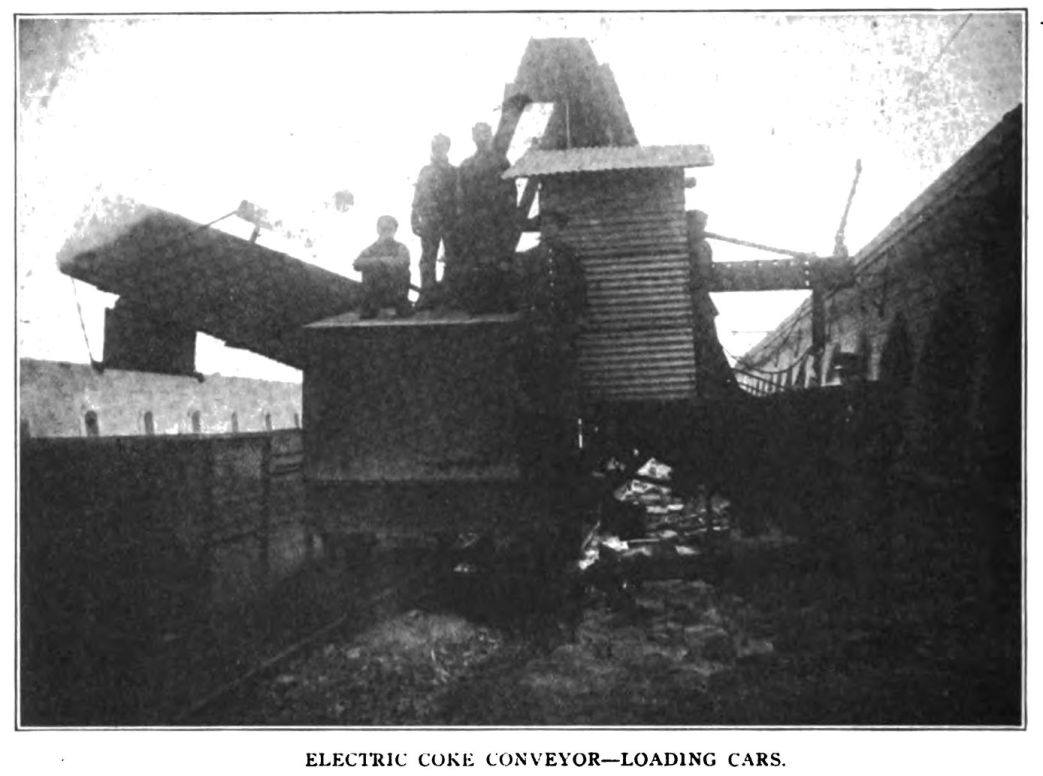

At one side of a row of these rectangular ovens is a wide track along which rolls a heavy steel carriage upon which is mounted the ram which pushes the coke out of the oven. On the other side of the row and between the ovens and the railroad track is another track carrying a combined screen and conveyor.

All the water man has to do is start the watering apparatus and it automatically, by the action of the water itself, moves back and forth. At all old plants a man must stand and hold the watering pipe, moving it about.

When an oven is ready to draw, the carriage carrying the ram is moved into position in front of the oven, moving with its own power. The machine is nothing more than a big ram with a rectangular head. The thick stem of the ram telescopes on itself and the uninitiated seeing it reach the length of a thirty-two-foot oven wonders where it is coming from.

While the machine is being “spotted” a couple of other men are placing the screen and conveyor in position at the opposite side of the oven. As soon as the signal is given that the conveyor is ready, the man on the machine gives the controller handle a jerk, the motor starts and in one minute the five ton of coke is not only out of the oven, but screened and in the railroad car. As soon as the oven is charged, the ram is started again, this time raised up, and one trip in and one out levels the oven as smooth as a cement sidewalk, and ram and conveyor pass on to another oven. Given enough ovens and changes of men, this machine will draw coke every hour of the twenty-four. Working single turn, twelve men will operate 100 ovens on forty-eight hour coke. To pull the coke alone by hand would take twenty-five men, to say nothing of leveling, bricking up, wheeling it to the cars and forking.

This is a real labor-saving machine, doing the slavish, exhausting work and actually lightening the burden of the workers that remain at the coke plants where such machines have been installed. At its best coke works are dirty, smoky, smelly places, but at a machine plant, such as I have described, the work is wholesome, pleasant child’s play compared to a hand operated yard. There is no doubt in my mind that the men required to run a machine coke plant will be of a higher, economic and intellectual status than those that furnish the labor power at an old style hand plant. Here is a case where slightly skilled workers have displaced or are displacing the roughest of unskilled labor and their status is an improvement over those they have displaced. On the other hand, we saw that the semi-skilled or slightly skilled laborers that displaced skilled molders lost status as compared with those they displaced. Thus the leveling goes on. The leveling which will soon make industrial organization as easy as craft organization is now.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v11n11-may-1911-ISR-gog-Corn-OCR.pdf