Art Shields reports on the labor scene in two North Carolina cities, Durham and Winston Salem, dominated by the tobacco, and more recently arrived textile, industries. North Carolina has historically been among the most unionized, and progressive, of the former Confederate states

‘Bull and Camels: A Tale of Two Tobacco Towns’ by Art Shields from Labor Age. Vol. 16 No. 11. November, 1927.

1. THE TOWN OF THE BULL

AND now we come to the native town of the bull, whose fame is flung over the universe. His sacred dust is inhaled by the cowboy galloping over the great open spaces; he helps the boys who join the navy to see the world to forget their troubles; and baseball players get $50 prizes for knocking the ball over his sign on the right field fence.

The wages of Durham tobacco and seamless hosiery workers run to about two dollars a day. And the cost of living is high. Milk is 20 cents a quart. A cynical Negro, whose children get very little of the life-giving fluid, suggested to me that what the town needed was less bull and more cow.

Bull Durham belongs to the stable of the Dukes—the Dukes, whose name has been given to a famous mixture and to one of the richest universities in the nation. Just three generations from a dirt farmer is this family, but aristocrats are they now. No dukes of the old world can show the resources of the owners of Bull Durham and the cigarettes and snuffs and chews associated with American Tobacco Co. Their wealth has flowed over the twin Carolinas, from tobacco it has spread into textiles, into a power monopoly and into higher education at Duke University.

Meet Old Washington Duke

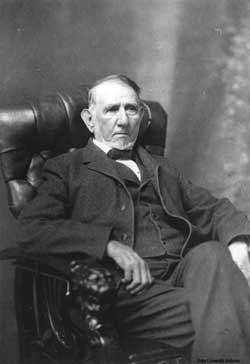

Enter the campus of this $40,000,000 institution and meet old Washington Duke, the founder of the line who died in 1905 at the age of 85. There the one-time dirt farmer sits back in a great sculptured chair, looking out over his chin whiskers, and perhaps wondering what it is all about. In the university library, not far away, the story of his rise from poverty to greatness is set forth in becoming reverence in the history of Durham. You read how the Confederate army took him away from his tobacco patch at the age of 41 and how he walked home 132 miles at the age of 45—but not to farm any more. He was fed up with farming, it appears. By walking home he had saved the capital of 50 cents, given him by a good-natured or gullible Yankee soldier in exchange for a Confederate five-dollar bill. With the 50-cent piece he went into the tobacco peddling business. And he saved his money, and he was an honest enterprising business man. And the 50 cent piece became a grand duke pile.

Surely any American boy can do the same. As the old ditty says:

“If you save up your pennies;

And save up your rocks

You’ll always have tobacco

In your old tobacco box.” Like Duke.

Low wages and welfare work do not go together in the factories of the American Tobacco Co. and its kin Liggett & Myers. They take their low wages straight. And no company unions either. They take their open shop straight.

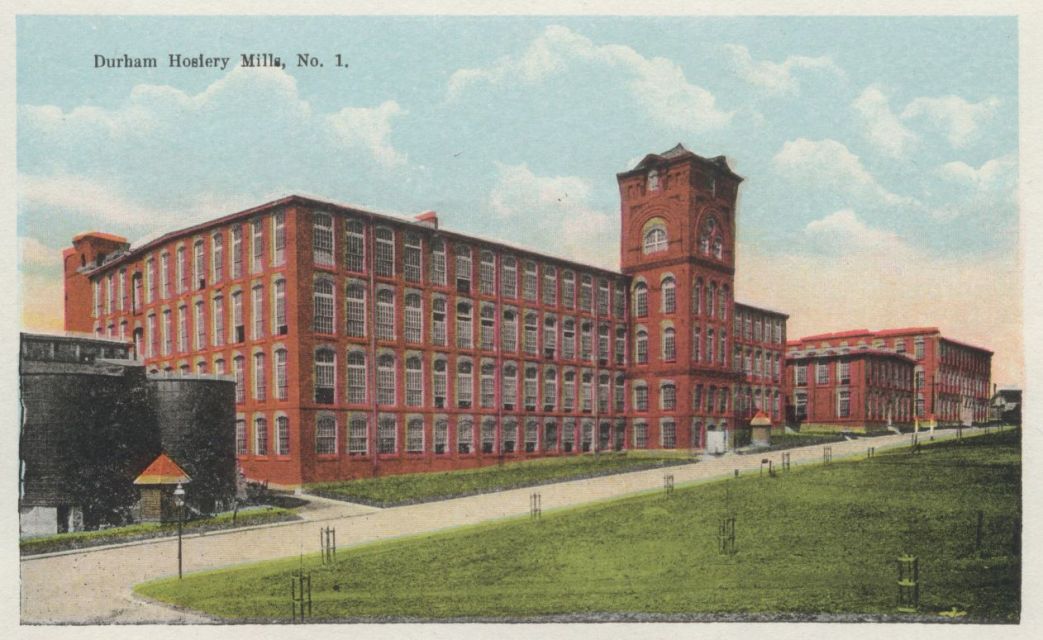

Carr’s Company Union Dies

A few years ago Durham did boast one of the few company unions in the South. But it lasted only two years. The late Julian Carr, head of the $9,000,000 Durham hosiery company, took a flier in industrial democracy in 1919 and installed a “house” and “senate” in all of his mills except the one where Negroes worked. The son of a slave-holder he let the Negroes take their open shop straight. Industrial democracy carried on in the white mills till 1921 when Julian Carr asked for a cut. The “house” and “senate” duly assented to a 25 per cent reduction. But Julian Carr was not satisfied, he wanted 43 per cent, and so the experiment in industrial democracy died. Since then the American Federation of Full-Fashioned Hosiery Workers has been educating the workers into the meaning of real unionism. When the Carrs opened a full-fashioned unit in 1922 the union came South, and to date has conducted two strikes for recognition of the union in the Durham full-fashioned units.

The full-fashioned union lacks recognition but its members carry on an underground organization and it is the vanguard of unionism in the manufacturing industries of Durham. Recognizing that all Durham labor has a common fight against the two open shop families that dominate the town the full-fashioned organizer, Alfred Hoffman, is an active spirit at central labor union meetings and works hand in hand with the representatives of all the other unions there. When we came to Durham we found the building trades unions on the eve of a serious crisis with the Dukes. The Duke Foundation that handles the university’s endowment fund had taken the construction work at the campus away from the George A. Fuller Co., a nationally known union contracting firm, and turned it over to Southern Power Co., an open shop subsidiary of Duke Power Co., thus keeping the money in the family and in the open shop. For two years the Fuller Co. has been employing an average of 500 workers under a union agreement, a 10-year building program is still to come, and that organized labor cannot afford to be left out of it.

There is still a last minute chance that the Southern Power Co. will see the wisdom of dealing with the unions, and avoid the bad advertising that the university will get if it is put up on the non-union plan. But if a fight comes the Durham boys will need every bit of help the readers of LABOR AGE can give them, and one way to help will be to send out notices to your friends:

“Keep off Duke campus: unfair!”

The Durham unions showed their stuff in the Henderson strike: two of the locals assessing their members a dollar a week each for relief funds, and others donating funds from the treasury. These unions are confined to the old line crafts, and some of them are only partly organized. But their meetings are educational and interesting and their attitude is militant.

In the next bull fight—bet on the men.

II. CAMEL-MAKERS HEAR A NEW AGITATOR

In the sweet tobacco atmosphere of Winston Salem, N.C., where all the Camels in the world are made, I found a new spirit of confidence among trade unionists.

This largest city in the Tar Heel state is an open shopper but the unions are making encouraging gains. The carpenters’ local that had slumped to 15 members a few months ago is up to 250 now., All the building trades have gained, and most hopeful of all, the tobacco workers’ organization is showing some real life.

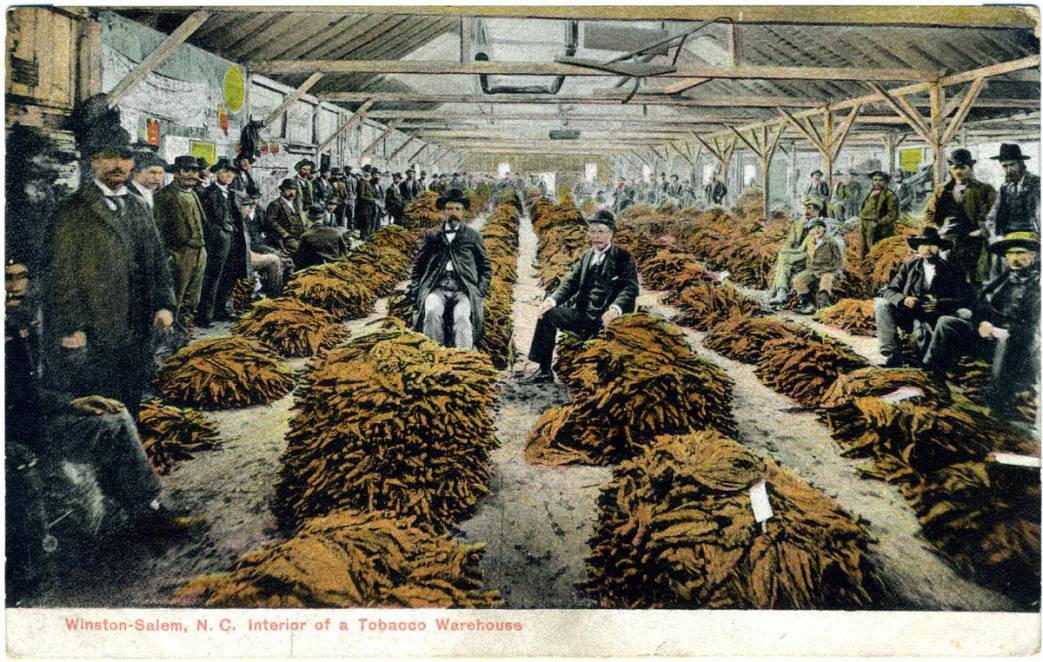

Tobacco is the basic industry. Winston Salem has risen with the weed, like a weed, its population doubling in 10 years, and the test of the labor movement here must be its strength in tobacco.

A half dozen mechanics, and Edward L. Crouch, sixth vice-president of the Tobacco Workers’ International, were discussing prospects in the little labor hall within a stone’s throw of the nearest R.J. Reynolds’ plant.

“All the colored men who came to our last meeting signed up,” Crouch was saying.

“Yes,” drawled a tall, blue eyed man: “Some of these n***s’ll stick a heap better than the white men.”

Others disputed this, but all agreed that prospects were encouraging.

You see an agitator has come to town, and has been helping Crouch to stir up the tobacco workers. Such an agitator you never saw, with the greatest line of statistics you ever saw; all about the profits of the boss. He told the Camel makers they were working in a gold mine, and his story wrought a change. Those two-dollar a day men whose stomachs were turned down to a “fat back” and meal diet began to get pork chop and sweet potato pie appetites. A wonderful agitator, and you would never guess who he was. No one else, but—do not gasp: no one else but a big New York brokerage house that took an office in Winston Salem to sell tobacco stocks to the home folks. Charles D. Barney & Co., it was, with a lot of literature that made tobacco securities attractive by publishing the bonanza balance sheets of the Big Five companies.

Barney Ra’‘ses Hell!

Barney told the Winston Salem boys stories like this: that $740 invested in R.J. Reynolds in 1913 would be worth $8400 now, in addition to $1587 dividends, an average return of 16 per cent. Barney said that last year the firm made $26,000,000 net profits, and by doing some figuring themselves the folks who did the work could find out that the coupon-clipping stockholders got about three times as much last year as the wage workers did.

Agitator Barney spilled the beans: five years ago the Reynolds people put a Winston Salem labor paper, “Unity and Justice”, out of business for the crime of running the year’s profit reports, with comment. The company had the banks threaten to cut off the credit of advertisers.

Crouch puffed a Clown as he talked of the likelihood of Camels becoming a union smoke, with the whole line of Reynolds pipe, and snuff, and twist and plug coming into the label ranks too.

“I was working in the plant where they make the Prince Albert tins when we organized Reynolds in 1919,” he said. “We had 14,000 members here then and the union was recognized till the agreement expired in 1922. This was a union town in those days and it is going to be again.”

Five years’ experience without the protection of a union; five years at two dollars a day, and perhaps less —Crouch and his friends picked up 309 pay envelopes recently whose average came to less than ten dollars— have taught a lesson in Winston Salem. And Crouch believes that after the next big drive the workers will stick. What is needed is money for the drive from the outside: the tobacco workers’ international lacks the needed resources: then a drive that will seize the town like an evangelistic campaign—a drive with the gaiety and mass appeal of a labor Chautauqua in the mining camps.

Union Baseball

Then a labor baseball league too, Crouch thinks. For surely as little apples grow the boss will start sports and picnics and all the tried counter attractions as soon as the union rises again. Reynolds gave the workers 16 baseball teams in 1919 and 1920, when the union was strong. And the answer to that, Crouch thinks, is to have a workers’ baseball league, for if these North Carolina boys can’t play ball they are not happy.

Crouch was much interested in the union baseball league that Carl Holderman of the American Federation of Full-Fashioned Hosiery Workers started in the New Jersey-New York district as a set off to the company teams. But that is a whole story in itself which Carl should write for LABOR AGE.

They need organization badly in Winston Salem. Young Dick Reynolds has been too busy spending hundreds of thousands on the Great White Way, or disappearing in St. Louis hotels under aliases to give much care to the 11,000 workers in the family plants in Winston Salem. Note that figure 11,000. It testifies to the increase in productivity of the American industrial machine. These 11,000 now turn out many more Camels and Prince Albert canfulls than the 14,000 did seven years ago. Better automatic machinery and scientific time studies have done it.

They need organization in a town where the average factory workers’ wage is around two dollars a day, and building trades men get about half as much as in New York, Pittsburgh, St. Louis and the better organized northern cities. Carpenters getting 45, 55 to 70 cents an hour, for 10 hours a day in a booming town need organization and are beginning to get it.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v16n11-nov-1927-LA.pdf